The sports performance industry is currently in uncharted territory, simply from the standpoint of the uncertainty shadowing how and when we will all return to doing what we do best. On top of that uncertainty comes this crucial question: As coaches, how do we ensure it is safe for our athletes to return to physical activity? Any strength and conditioning coach will agree that the concern over soft tissue injuries is at the forefront of our minds during this process.

As we begin bringing back our athletes, many of us have realized that you can tell and show an athlete what to do independently, but their training intensity is not the same as when they are being coached. We can tell them what to do, but without a coach correcting their technique, creating motivation, or pushing them to strive for more, the training effect is not the same. Therefore, despite all the time spent on at-home training programs and trying to hold your athletes accountable, they still may not be prepared when circumstances allow a return to training or competition.

One of the major steps we are taking to ensure that our athletes will be prepared when their season begins is extending our sprint technique warm-up. Share on XAt Varsity House Gym, one of the major steps we are taking to ensure that our athletes will be prepared when their season begins is extending our sprint technique warm-up. Simply put, this is a way for us to stress the mechanics of sprinting without stressing their joints and tendons with the higher forces and velocities of actually sprinting. There are three reasons I believe extending your sprint prep warm-up is the key to helping prepare your athletes for return to their sport:

- The low-impact nature of warm-up drills will not overtax their tendons and joints, and they will be more prepared for the higher intensities of sprinting.

- By extending our warm-up process, we are building in some extra work capacity through the increase in tonnage (by yards) of the amount of work the athlete performs. For example, we will have them do all their sprint prep work through 20 yards down and back. After six drills, we will have already built up to 240 yards of work without taxing the athlete as much.

- Making athletes perform more reps of their sprint technique will give them more opportunities to figure out how to solve the complex motor issues of live sprinting.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9079]

What Does an Extended Sprint Warm-Up Look Like?

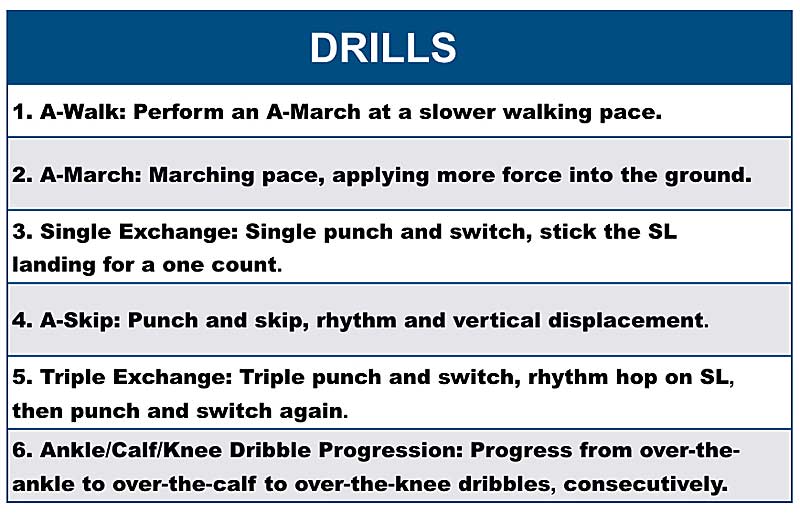

When we perform our sprint prep series, there are, generally speaking, approximately 4-6 drills that we do, depending on the time of year, the time within the training block, and the experience of the athletes we work with. Along with that, we work from slow to fast and simple to complex in the drills that we choose to do for that day. This allows the athlete to build on one drill into the next, again giving us more reference points to pull from for technical cues.

As you can see, all of the drills follow the progression of slow to fast and simple to complex—simply adding a level of intent or speed to a drill is a progression in itself. Therefore, each time you add speed to a drill (i.e., A-Walk to A-March), you require the athlete to solve the same movement problem in a more intense environment. Even a small change in pace can expose imbalances or technical inconsistencies with an inexperienced athlete.

Next, when it comes to the warm-up process, we do our volume considerations in three- or four-week waves, again giving our athletes optimal opportunities to adapt to the stimulus. Yet the way we work, it actually happens in reverse: We have a longer warm-up during the first 1-2 weeks, as it helps our athletes adapt to the training stimulus a bit better. We may perform our sprint prep drills for 20+ yards or meters for two rounds during the initial weeks.

As athletes become more efficient with the warm-up process, we can then decrease the volume and increase the intensity of the warm-ups by introducing some more complex warm-up options. When we lessen the volume, we can start by lowering the number of sets first and then lowering the distance traveled, as we want to still allow them actual time to adapt to the more complex stimuli.

Why It Works

I previously mentioned the three reasons that extending the sprint warm-up helps to prepare athletes for return to their sport. Here, I explain the thinking behind those reasons as well as how to apply it with your own athletes.

1. Has a Low Impact on Joints and Tissues

The best ability is availability. Coaches across all levels cannot express this mantra enough to their athletes. This will be our #1 job as strength coaches—ensuring our athletes are available when it is time to hit the field. Athletes will not be ready to start moving at fast velocities on day 1, week 1…maybe not even month 1. Therefore, we need to make sure we initially do things that are low impact and joint- and tissue-friendly to ensure continued availability to train and play.

As a return-to-play policy, extending the warm-ups will help increase the resilience of the athletes’ tissues, helping them become more accustomed to those forces over time. Share on XThe low-impact nature of warm-up drills like marching, skipping, and dribbling make them great places to start. Performing these drills allows us to reintroduce proper sprinting mechanics without the added velocities and forces of live sprinting. As a return-to-play policy, extending the warm-ups will help increase the resilience of the athletes’ tissues, helping them become more accustomed to those forces over time. The resilience and stiffness of their tendons will correlate highly to their readiness to jump, throw, and sprint, as it will directly affect the stretch-shortening cycle of the muscle1.

Given the amount of time many of our athletes have been on the couch, their tendons will not have the prerequisite tissue stiffness to handle the necessary intensities. Using low-impact warm-ups to help re-establish tendon stiffness and resilience will be vital to helping them return to play. Providing more stiffness in the tendons will prevent overloading our athletes to perform activities that their bodies are not prepared to perform.

2. Increases Work Capacity

A major obstacle to returning to play will be the athletes’ level of conditioning (or lack thereof). Even when experienced athletes work out on their own, there can be a different training stimulus then training in the gym environment. For example, one of our elite-level athletes in the NBA was still training on his own throughout the COVID-19 pandemic; however, the minute he came back to training, he was highly detrained, and it took him about two weeks to get back to where he was before the quarantine started. Considering that reality, if an elite-level athlete can take two weeks to get back to regular training, what do we think high school athletes will be like?

Using the warm-up to gain work capacity is an easy layup for creating additional opportunities without the direct stress of a conditioning protocol. Even something as simple as a few 50-yard shuttles will be a challenge for athletes who have been slacking during the time off.

Using the warm-up to gain work capacity is an easy layup for creating additional opportunities without the direct stress of a conditioning protocol. Share on XExtending the pre-sprint warm-up process creates an opportunity to increase that work capacity in a low-impact environment. Performing the drills with optimal technique over distances of 20 or 30 yards/meters will tax both the muscular and cardiovascular systems of athletes who may have been less active than their norm. You can also opt to perform drills stationary, using time instead of distance, which can give you greater control over the work-to-rest ratios and more ability to dial in the conditioning aspect. Thankfully, the general low intensity of warm-up drills can allow you to have athletes perform them for extended periods without worrying about overworking the athlete.

Using these tools to sneak in extra “conditioning”—without the high impact or intensity of real conditioning—will be paramount for an efficient return to play. We can push the time of work without the fear of detrimental soft tissue injuries, as long as we maintain low intensities over an extended distance or time. Building back a base of basic work capacity will help us lay the groundwork for increased work down the line—and now, more than ever, this needs to be at the forefront of our consideration.

3. Improves Technical Proficiency

When it comes to sprinting, getting your athletes to understand the proper postures and positioning is an important step. Yet, we aren’t always able to spend the amount of time we probably should on giving the athlete’s brain time to figure out the proper positions.

Many of us are familiar with the 10,000-hour rule, which states that it may take 10,000 hours to become an expert at something. Especially when it comes to something as complex as sprinting, this rule is something that we can apply—so why not try and get more practice in? Literally reaching 10,000 hours will probably rarely happen, but mastering an essential skill for sport performance with intent and deliberate practice is something that we can work toward.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9082]

When working with younger athletes in particular, it may take them longer to grasp the complex concepts of sprinting, so we should give them more opportunities to figure out those issues. By extending the sprint warm-up process, we give them those opportunities at focused practice to keep getting closer to mastery of the skill of sprinting. As they continue to build and grow their understanding of the desired postures, patterns, and shapes they are trying to accomplish with their bodies, their understanding of technical cues will grow in concert.

By extending the sprint warm-up process, we give younger athletes opportunities at focused practice to keep getting closer to mastery of the skill of sprinting. Share on XAs coaches, we can shout whatever cue we want, but if our athletes do not understand what the cues mean, we are wasting our voice and their time. If we can grow their base of movement knowledge, we can provide more reference points as to what patterns or shapes they are trying to accomplish. A novice athlete may not understand the concept of good frontside lift and why it is important, but if we can give them a reference point of an A-Skip or A-Run, they can connect those dots more easily.

By extending the warm-ups and benefitting from the combined effects of improved work capacity and technical proficiency, our athletes can also become more accustomed to maintaining those postures for longer periods. This may be something more pertinent to track coaches, where middle distance runners may be forced to maintain technical proficiency under extreme levels of fatigue. But even team sport athletes can use this concept—a soccer athlete may have to make a big push in the final minutes of the game under fatigue. Even though the technique of the sprint mechanics may not be the same, the idea of being able to pull from those capabilities while fatigued is still important.

Warming Up with a Purpose

The simple act of extending the sprint warm-up process and using these drills as a chance to get some more light and extensive plyometrics before a training session will be a saving factor for many of our athletes returning to play. Their joints and tendons will be very lax and not ready for the intensities of all-out extended sprints, and we need to be prepared to give them the proper time to get back into shape. But, let us not forget the reason we even do sprint prep to begin with—the complex movement patterns of sprinting need to be constantly practiced and refined, even for the best athletes in the world. By using an extended warm-up of upward of 20 meters, we give our relatively novice athletes more chances to understand these complex patterns.

This time in history may be unprecedented, but it does not mean that we do not have the tools to deal with it. Share on XAbove all, we as coaches need to ensure that we do no harm to our athletes: Their health is our job to maintain and improve. This time in history may be unprecedented, but it does not mean that we do not have the tools to deal with it. By simply moving around some volume in different areas, we can give our athletes the best chance to be prepared for their respective sports as we start the slow return to normal activities. And using the sprint prep warm-up in an extensive fashion and as a low-level plyometric to prep the body for more intense activities is a major key to getting them prepared.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Kubo K, Kawakami Y, and Fukunaga T. “Influence of elastic properties of tendon structures on jump performance in humans.” Journal of Applied Physiology. (1985). 1999;87(6):2090‐2096. DOI:10.1152/jappl.1999.87.6.2090