[mashshare]

You breathe about 20,000 times per day, so imagine the impact that breathing can have on daily living—your habitual posture, your repetive movements, everything that influences your body’s ability to move and perform.

How much time do you or your athletes typically spend on warming up and mobility and flexibility routines? Going through post-session cooldown routines full of static stretching? Pre- and post-session foam rolling or myofascial release?

No doubt all this stretching, rolling, and (to use Kelly Starrett’s parlance) smashing your soft tissue accounts for a considerable amount of training time. Much of this is time well-spent in improving the ability to make the shapes required for effective performance.

How many of you, though, go through 10-20 minute warmup routines, mobility work between sets, 10-15+ minutes of cooldown, maybe even separate and specific mobility and flexibility sessions, yet fail to see significant improvement in these areas?

“Every breath you take, every move you make, every bond you break, every step you take.” – The Police

If we’re completely honest, mobility and flexibility work is not the most exciting part of training. While it’s necessary and essential, it often seems tedious and repetitive. Unlike other aspects of strength and conditioning, it is often difficult to see the kind of consistent progress that you can with times, loads, and numbers. As a result, many athletes lack the discipline to perform sessions in which the rewards are not immediately apparent.

The longer these types of sessions last, the more likely that athletes will rush through them or skip individual aspects. That’s just human nature. Of course many educated and dedicated athletes understand the benefits and will follow the program to the letter and “get it done.” This doesn’t change the fact you will encounter many athletes who do not have this attitude. For them, you need to implement training strategies that bring real and obvious benefits.

Chris: The Problem

I have to hold my hand up and admit to being the kind of person who needs a quick remedy with a real and obvious effect. When you feel something is clearly working, it is easier to maintain that discipline.

I have struggled for a long time with mobility restrictions, and tightness in different areas, primarily in my anterior hip, calves, and ankles, particularly down my right side. I have at different times tried a consistent application of various techniques to remedy this condition. Static stretching of key muscle groups—hip flexors, hamstrings, adductors, and lower back. Dynamic flexibility warmup protocols. Foam rolling and other self-myofascial release techniques. I have watched many mobility WOD videos and incorporated band distraction into stretching routines.

Some of these techniques have given me short-term relief or benefits. Others have had little impact. I have been the recipient of high-level therapeutic intervention on more than one occasion and with more than one experienced practitioner. Having a skilled physiotherapist or manual therapist put their hands on you, massage and manipulate your joints and soft tissue, is of course far more effective than self-remedies. The effects are much greater and usually last a bit longer. But having not played sport at a high enough level to receive daily intervention, I find that by the time of my next weekly appointment I am back to square one.

A combination of therapeutic intervention and self-corrective techniques have been enough to stop my lack of mobility and flexibility from worsening, or at least slowed the decay. It has not, however, led to obvious enduring improvement.

One intervention, though, did lead to a bit of a “Eureka!” moment. I had previously read articles on the effects of proper diaphragmatic breathing on posture and movement quality. In particular, some postings of Ryan Brown (of Dark Side Strength and Conditioning) on the Juggernaut Training Systems website were enlightening.

The concept of breathing improving posture and movement quality was interesting to me. Improving physical performance without increasing the workload and training strain for me or my athletes sounded too good to pass up. But daily life got in the way. With restricted training time I barely had time to fit in the big-ticket items like squats and power cleans and so—stupidly, I think—I didn’t implement the breathing drills.

Until recently, that is. As Dr. Tom Nelson mentioned in this article, something as simple as breathing is too often and too easily dismissed. Becoming increasingly frustrated with my jammed-up hip, I decided to give it a try.

Lying flat on my back on the gym floor, I spent several minutes trying to relax, breathing as deeply as possible, then deeply exhaling. As I was lying there contemplating how ridiculous I probably looked, I felt a rather bizarre sensation. My psoas—previously strung as tight as a piano wire—suddenly and completely released. There was real and obvious relief.

When I stood up and walked around, pulled my knee high into my chest, and performed a few squats, the increased mobility and freeness with which I could move my hip was hard to believe. Even just walking around, my hips felt more aligned, like my right femur was sitting more properly in the socket, and I wasn’t being pulled and rotated out of position.

I probably should not be surprised by such emphatic results. The summary of Dr. Eric Janota’s lecture in the same article as Dr. Nelson mentioned that the “psoas is intimately attached to the diaphragm.” Therefore, anything that encourages proper movement and alignment of the diaphragm can reasonably be expected to have a beneficial influence on the psoas.

Steph: Anatomy and the Solution

At this point we will discuss some basic human anatomy and physiology. Breathing is an active process, with the primary muscles of respiration being the intercostal muscles (located between the ribs) and the diaphragm. During inspiration these muscles contract. The intercostals contract to elevate the ribs and sternum, increasing the front-to-back dimension of the thoracic cavity. Contraction of the diaphragm moves it downward and increases the vertical dimension of the thoracic cavity. This lowers air pressure in the lungs, with air flowing in.

During exhalation, these muscles relax. The diaphragm, ribs, and sternum return to their resting position and the thoracic cavity returns to its pre-inspiratory volume, increasing pressure and resulting in air being exhaled.

Incomplete or faulty breathing patterns lead to problems that affect the habitual positions of these structures and ultimately the posture. There are three main types of breathing: clavicular breathing from high up in the shoulders and collarbones, chest breathing from the center of the chest, and abdominal breathing. It is the latter that engages the diaphragm the most and activates the vagus nerve, triggering the body’s relaxation response that is necessary for renewal, healing, and repair.

One explanation for the relief Chris and others have felt through incorporating proper diaphragmatic breathing into their daily routine could have to do with regulation of the autonomic nervous system (ANS). There are two components to the ANS: sympathetic (SNS) and parasympathetic (PNS). The PNS down-regulates the nervous system, calming the body, promoting relaxation, rest, and sleep, and slowing down the heart rate and breathing.

The vagus nerve controls the PNS. By being aware of the anatomy of breathing, you understand the mechanism of a sudden release of chronic tension in the psoas. Deep diaphragmatic breathing activates the vagus nerve, stimulating the PNS to calm and relax the body’s muscles.

There is a more substantial relationship between the diaphragm and psoas. Anatomically, both structures have origins in the lumbar spine. If you are looking for a greater connection between the deep breathing muscles and the psoas, I recommend educating yourself in anatomy trains and the myofascial meridians. Chris’s chronic problem areas with large amounts of tension follow precisely along a myofascial line, with the greatest tension in the right ankle and hip. This line connects the breathing muscles and the anterior musculature such as the psoas.

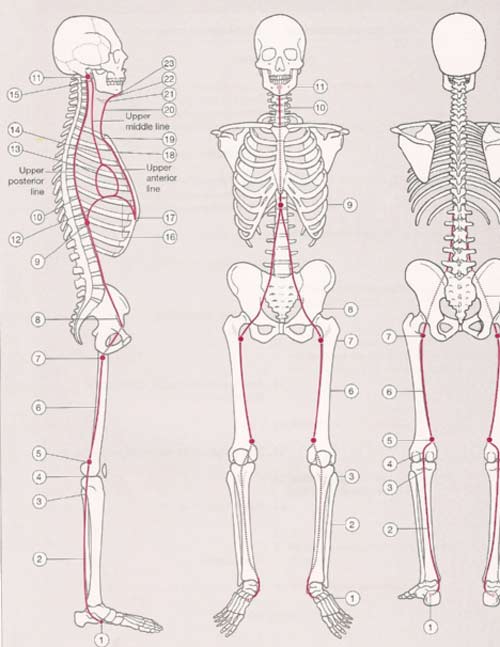

Myofascia surrounds the muscles, making an interconnected web throughout the entire body that allows transmission and dissipation of tension and compression across the body. This myofascial system also allows for the transmission of muscle movement. According to Dr. Thomas Myers, there are 12 myofascial meridians or lines in the human body. A breakdown at one point along these lines can be realized as a symptom anywhere throughout that line. Relating this to Chris and his issues, his problematic right side follows a certain pattern that corresponds exactly to the deep front line myofascial meridian.

This deep front line is like the myofascial core running from the bottom of the foot, passing up behind the bones of the lower leg and knee, and continuing up inside the thigh. Here it divides into a line passing in front of the hip, pelvis, and lumbar spine, while another track goes up the back of the thigh. At the psoas-diaphragm interface, the deep front line goes up through the rib cage along numerous paths and finishes on the underside of the neurocranium and viscerocranium.

Chris has suffered from plantar fasciitis on his right side and has tight medial soleus, hip adductors, medial hamstrings, and right psoas. Continuing up, he struggles with flail chest and a tight shoulder complex closely related to this frontal line.

If Chris had a problem or knot along the line near the psoas, the deep breathing might have been beneficial for several reasons. In addition to activating the vagus nerve and stimulating the PNS to relax his body, it also may have helped to soften the myofascial knot through active muscle contraction to release his psoas. It is incredibly hard to manipulate the diaphragm manually. Therefore, the deep breathing could have helped to unwind whatever tension had built up over years of training, habitual poor posture, and inadequate breathing patterns.

Summing up

Bad habits and lazy, incomplete breathing can lead to poor posture and misalignment of the rib cage, diaphragm, and pelvis. Regular correct diaphragmatic breathing can help you and your athletes stimulate the PNS to relax the body and musculature to release tension developed and stored by these faulty breathing mechanics and associated postures.

Practicing deep breathing and relaxation on a daily basis can help restore posture, mobility, and lower back health, and correct movement patterns. Something as simple as correct breathing patterns can improve pelvic alignment, removing anterior tilt and generating immediate improvements in sprinting postures and performance. Correct and efficient posture is essential in assuming the right positions to generate force in big-ticket exercises such as the squat, in which poor breathing patterns and postures can lead to inferior performance and a reduced ability to produce force.

Spend time with your athletes cueing correct pelvic alignment. Start them on the floor as if they were about to perform a basic crunch. Ensure that their backs follow a normal neutral curve and have them breathe deep into their back, using their abs as a brace to maintain abdominal tension and draw air up into their lungs. If they have difficulty breathing correctly in this position, you can regress the drill by having them place their feet up against a wall with knees tracking over toes and hip and knees at 90 degrees to give additional stability to the hips. Athletes with greater body awareness, can be progressed to lying with their legs out straight and even incorporating breathing drills into standing and other exercises.

Proper diaphragmatic breathing is an active process, but your athletes should also try and relax as much as possible while trying to maintain the right positions. Ask them to practice five minutes of full inhalation and exhalation and see how this benefits their habitual posture, mobility, force-generating capabilities, and performance.

We hope you find the information in this article useful and would love to hear your experiences. If you are interested in learning even more about these ideas, research more from the likes of Ryan Brown.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]