Despite all the advances in strength coaching, sports medicine, and equipment technology, about one million individuals each year still suffer an Achilles tendon injury. These injuries are devastating for athletes—even with the best care, many athletes with torn Achilles tendons never return to their pre-injury performance levels.

At the pro level, an Achilles rupture is often career-ending. For these reasons, a proactive approach is needed, especially in sports such as soccer, football, basketball, and distance running, where the incidence of Achilles tears is highest. My approach involves a five-step, progressive exercise model, followed by a few “Achilles Hygiene” suggestions for keeping this tendon strong, flexible, and healthy.

(Lead photo by Ryan Paiva, LiftingLife.com)

The Fragile Achilles—Not!

Anatomy textbooks often give the impression that tendons are rigid, cable-like structures that connect bones to muscles. Not quite, as tendons can stretch up to eight percent of their resting length. They are also active tissues that act as biological springs that can stretch, store energy, and recoil to produce or amplify force. Let’s look at a few rather extreme examples of the resilience of the Achilles.

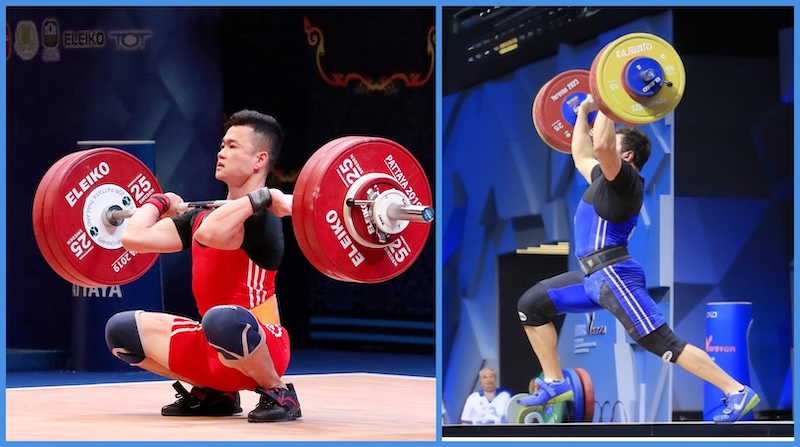

Note the positions of the ankles of the two weightlifters in Image 1 below. Not only are their Achilles stretched to extreme lengths, but they are under high loads. How extreme? How much load?

If preventing Achilles injuries is a priority, athletes should train the Achilles to react to rapid, large-amplitude movements under load..., says Kim Goss. Share on XConsider that six male lifters have clean and jerked more than triple bodyweight, and the current absolute world record is 588 pounds. On the women’s side, a 108-pound woman clean and jerked 273 (over 2 ½ times bodyweight), and the heaviest clean and jerk by a woman is 425, performed at the 2016 Summer Olympics. Data on the strength levels of NFL players is scarce, but I assume that few NFL players can clean 425 pounds.

Besides enabling them to lift heavier loads (by allowing them to catch the barbell at lower heights), the lifter’s large-amplitude/high-load training protects against Achilles injuries. Let’s look at three examples of how using the proper training stimulus can help when things go wrong.

In Image 2, a female weightlifter awkwardly misses a jerk with 279 pounds, which represents 169 percent of her bodyweight. Her front ankle collapses outward, and the Achilles of her back leg is under extreme stretch when her leg plants and again when her left knee buckles. You would think these positions with such heavy weights would seriously injure this athlete, but she walked away just fine and returned to the platform for her next attempt and successfully lifted 293! Such great escapes are common in weightlifting—let’s look at two more.

In Image 3, two weightlifters awkwardly collapse under cleans, the lightweight female with 257 pounds and the male with 478, weights exceeding double their bodyweights. Their Achilles were under extreme stress in both misses, yet neither athlete was injured.

What can we learn from these three lifters? One answer is that if preventing Achilles injuries is a priority, athletes should train the Achilles to react to rapid, large-amplitude movements under load. However, for poorly conditioned athletes, such stimulus takes an introductory period of preparation, which includes avoiding specific high-stress conditioning methods. Consider the warning of Posturologist Paul Gagné, a strength coach who has trained over 500 NHL players, and his experience with push sleds and hockey players.

“Because pushing sleds places the Achilles under load throughout an extreme range of motion, I’ve seen many hockey players have problems with their Achilles, particularly the first time they try them,” says Gagné.

Likewise, I’m a proponent of the Olympic lifts for preventing Achilles injuries, and I make the case in a previous article as Achilles injuries are virtually non-existent in that sport. However, having athletes attempt full snatches or cleans during their first workout, particularly with maximal weights, may not end well. With that background, let’s look at an exercise program that can help you, or the athletes you coach, avoid Achilles injuries.

Step-by-Step Achilles Training

This program begins with exercises to develop stability, proprioception, and flexibility. It progresses into large amplitude, dynamic movements. I did not invent any of these exercises, and many alternatives work just as well—these are just ones I’ve used with athletes, so I’ve seen first-hand their effectiveness.

Excessive valgus places extreme stress on the Achilles and reduces the athlete's ability to produce force. Fortunately, many exercises can help reform the arch, says Kim Goss. Share on XThe first two steps can be performed simultaneously, but I recommend performing the final three sequentially because each builds upon the conditioning of the previous step. Specifically, the exercises in the third phase require considerable ankle flexibility, and the exercises in the remaining phases involve high-speed movements with high coordination requirements.

Step 1: Reform the Foot Arch

Valgus is a condition in which the feet collapse inward. Excessive valgus places extreme stress on the Achilles and reduces the athlete’s ability to produce force. Fortunately, many exercises can help reform the arch.

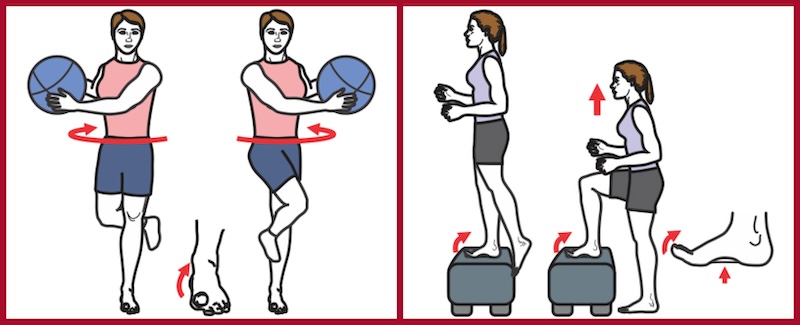

Image 4 shows two exercises Gagné prescribes to athletes with valgus feet, which are best performed barefoot:

-

- Hold a weight (such as a medicine ball), stand on one leg, and lift the big toe of the support leg. Holding the weight at about waist height, rotate side-to-side while holding up the big toe. Repeat the same number of reps for the other side.

- Perform a front step-up with the big toe up on the support leg. To prevent pushing off with the back leg (to focus more on the front leg), lift the toes of the back foot. Align the working knee with the big toe during the exercise. Repeat the same number of reps for the other side.

Step 2: Restore Ankle Flexibility

“Fascia is connective tissue that surrounds and intertwines with the muscles,” says Gagné. “With inactivity, the fascia loses its flexibility and becomes weaker, making the muscles and tendons more susceptible to injury.” Variables such as excessive sitting, wearing improper footwear, and performing too much partial-range training can cause the fascia to restrict the ankle’s range of motion—more on this in the Achilles hygiene section. This flexibility issue must be addressed in the early stages of an Achilles training program training.

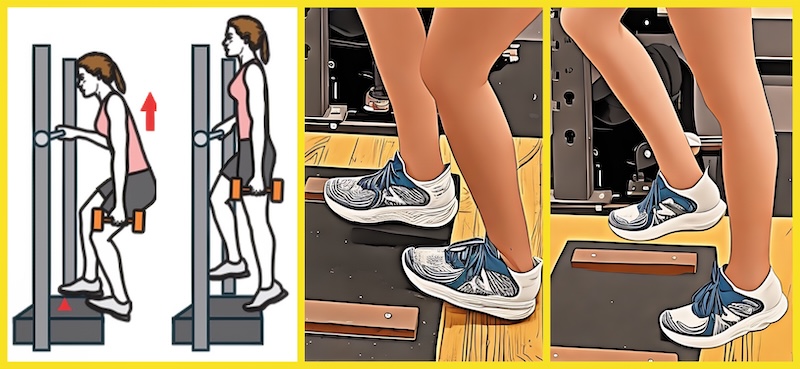

Image 5 shows a dynamic stretch of the gastrocnemius and soleus that can be used with resistance. It is performed on a platform high enough so that the heel can extend lower than the ball of the foot.

The exercise begins with the working knee slightly bent (to emphasize the soleus), the free leg lifted slightly off the platform, and finishes with the working knee straight (to emphasize the gastrocnemius). Note that the free leg does not touch the platform at any time. For variety, the toes of the support foot can be pointed inward to increase the stretch on the calf’s lateral (outside) part, while pointing the toes outward increases the stretch on the calf’s medial (inside) part. The exercise can also be performed barefoot.

Step 3: Strengthen Pelvic Muscles that Stabilize the Knee

The study of anatomy and biomechanics tells us that “everything is connected.” Besides strengthening the lower leg, it’s essential to strengthen the muscles of the pelvis, particularly those such as the piriformis that externally rotate the upper leg.

For this phase, I prefer single-leg exercises. Single-leg exercises are especially valuable for lower body stability and lateral movement because athletes support themselves primarily on one leg when changing directions.

When I started working with a high school girls’ basketball team in Utah about 17 years ago, the coach had to spend about 45 minutes before practice taping ankles because most of the girls had been suffering recurring ankle injuries. I had these athletes perform these types of exercises as part of their conditioning, and it paid off.

Here is what Head Basketball Coach Heather Sonne said about the results. “After about six weeks of using these exercises, my athletes’ conditioning improved so dramatically that I no longer had to tape any ankles. In fact, the only ankle injury we suffered since performing these exercises occurred in the final playoff game of the year, and it was an unavoidable accident that happened when one of our players’ feet landed on top of the foot of one of our opponents.” Success leaves clues!

Besides strengthening the lower leg, it’s essential to strengthen the muscles of the pelvis, particularly those such as the piriformis that externally rotate the upper leg. Share on XImage 6 shows two types of single-leg squats, which, because one leg is extended, are often referred to as pistol squats. The first is performed between two platforms, such as weight benches, and the arms are used for assistance. When athletes can perform these squats without assistance, they should move on to pistol squats with dumbbells or kettlebells. (For more on pistol squats, Pavel Tsatsouline covered this exercise extensively in his book The Naked Warrior.)

Another exercise that belongs in this phase is the ankle squat. It is a full squat performed with the heels together and toes flared outward to position the heels inside the pelvis.

Weightlifting Sports Scientist Bud Charniga saw elite Chinese weightlifters perform this exercise in training halls and has high praise for it. Charniga said this exercise “strengthens the calf musculature, especially the soleus; by a process called reverse – origin – insertion – contraction. The soleus muscle is lengthened under tension; as the shins tilt forward. Subsequently, these muscles pull the shins backward as they contract. Returning the shins from the tilted disposition acts to straighten knee and hip; as all links are interconnected through ankle, knee and hip joints.”

After a period of practicing ankle squats, the next progression would be performing barbell squat jumps with relatively light weights (starting with the empty bar). Unlike the popular hex bar jumps, these are squats performed with a full range of motion of the legs and a slight “bounce” out of the bottom. This stretch stimulates the bouncing out of the squat position in the snatch and the clean, reinforcing the elastic properties of the Achilles. Also, with this variation, you barely leave the ground. These two exercises are demonstrated in Video 1.

Video 1. Ankle squats and barbell squat jumps are dynamic exercises that work the Achilles throughout a full range of motion under load.

Step 4: Perform Jumps and Hops on Level Surfaces

The next step is to get everything working together quickly with fast jumps and hops. First, let me put a plug in for jumping rope. Jumping rope enhances stability and coordination at high speeds. Often, when the body is not stable or the athlete’s coordination is poor, the body’s response is to slow down or not react quickly enough (think “ankle breakers” in basketball).

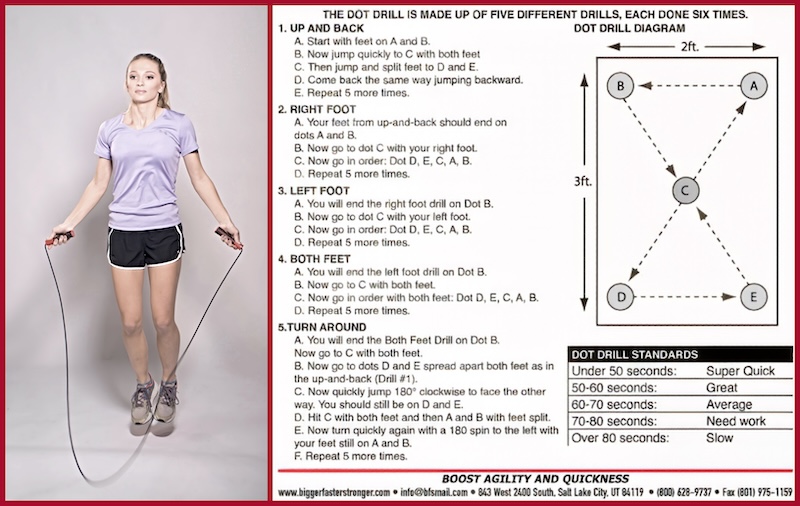

Another practical exercise, and one that does not require any equipment, is the dot drill (Image 7), popularized by Bigger Faster Stronger (BFS) for the past 40 years. The dot drill involves performing a sequence of double-leg and single-leg hops on a pattern of five dots that form an X. BFS promoted it as a warm-up for weightroom, plyometric, and agility training.

Step 5: Perform Dynamic Movements on Angled or Curved Surfaces

After developing a foundation of elastic strength with the previous four steps, you can safely proceed to more advanced ankle and Achilles exercises. These exercises should not only help prevent Achilles injuries, but also enhance the elastic properties of the connective tissues to amplify power. But first, a story.

The Air Force Academy is a run-first team, and we often joked that our unofficial motto was “Passing is for cowards!” Consider that in 1990, the year we upset heavily favored Ohio State in the Liberty Bowl, our quarterback Rob Perez was averaging only 30 yards a game passing and didn’t have a single touchdown pass the entire season. In one game, a bad snap from center resulted in our kicker throwing for more yards than our quarterback! Perez certainly didn’t have a cannon for an arm (nor were his 40-time or lifting maxes impressive), but what Perez did have from a physical perspective was the ability to change directions quickly to help him make great running plays.

After developing a foundation of elastic strength with the previous four steps, you can safely proceed to more advanced ankle and Achilles exercises, says Kim Goss. Share on XOne coach told me that what expressly set Perez apart was his ability to cut quickly on his inside leg, enabling him to change directions a fraction of a second faster and throw off the defense’s timing. Also, because our offense required the guards to pull, lateral speed was a critical athletic fitness component of these positions. For these reasons, we emphasized many conditioning methods to improve lateral speed.

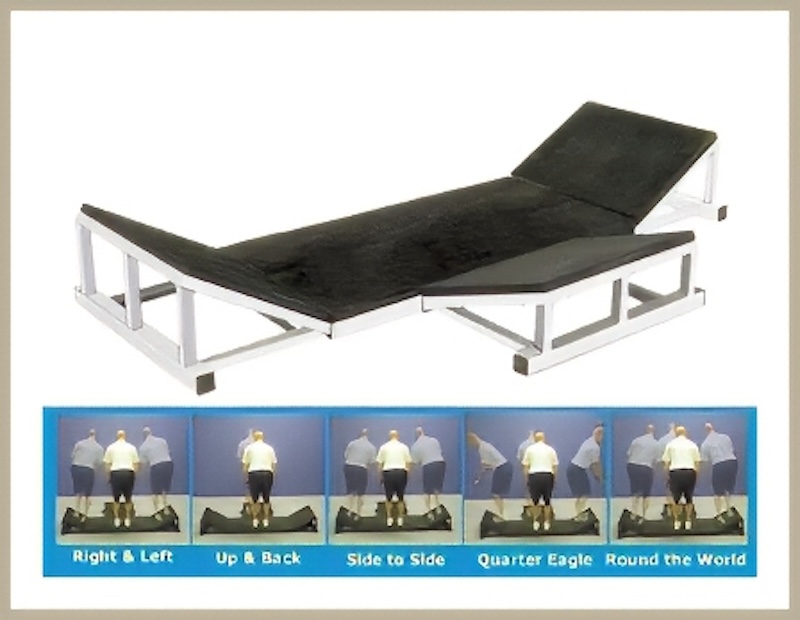

From a testing perspective, the 20-yard shuttle run was our best predictor test of lateral speed. Years of data we collected on the Air Force Academy Football Team found that performance in this test was associated with ranking on the depth chart. As for how to improve results on the 20-yard shuttle, I discovered that lateral jumps onto a slant board made significant improvements in the shortest time, particularly with our linemen.

About a decade after leaving the Academy, I started working for Bigger Faster Stronger (BFS) as their magazine editor. BFS developed a “Plyo Ramp,” a sturdy floor unit with three angled slant boards (two angles) and a non-slip surface. Unfortunately, the Plyo Ramp was large, heavy, and not practical in gyms with minimal space, so it never caught on in our primary market (high schools).

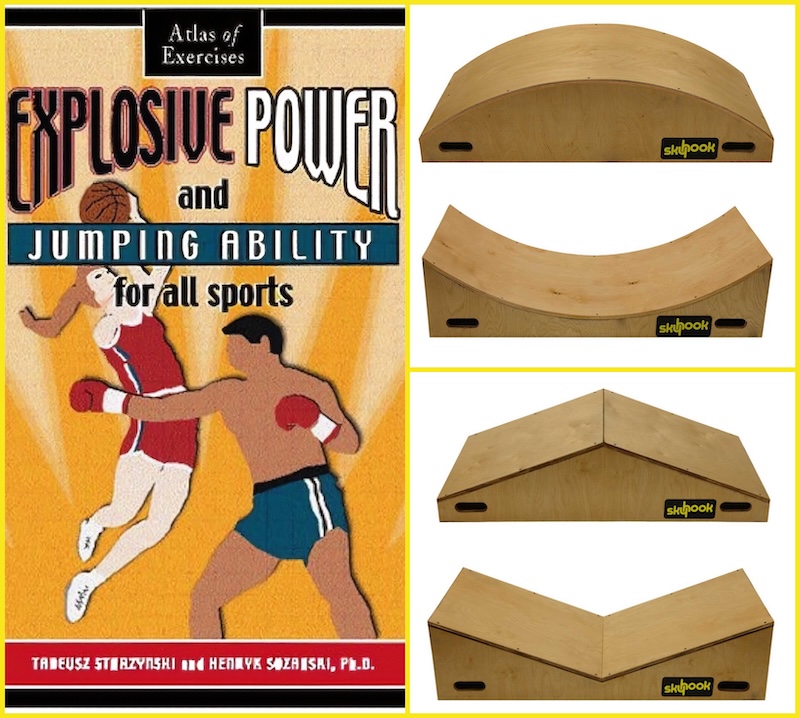

My interpretation of Occam’s Razor is that the best solutions are often the simplest and use the fewest elements, and Polish Plyometric Boxes fulfill this definition (Image 9). These concave and convex boxes, popularized in 1999 in the book Explosive Power and Jumping Ability for All Sports: Atlas of Exercises, are certainly simple. Further, they are relatively light and don’t take up much space.

Polish Plyometric Boxes enable the athlete to stretch and strengthen the Achilles through more extreme ranges of motion at high speeds. Resistance can be added with a weight vest or, as shown in the Explosive Power book, by holding a barbell across your shoulders.

The video below shows several Polish Plyo Box drills, dramatically demonstrating the ankle’s ability to react quickly to unique environments.

Video 2. Shown in this video courtesy of Skyhook, Polish Plyometric Boxes are practical tools for rapidly stretching and strengthening the Achilles through a wide range of motion.

Exercise is key to preventing Achilles injuries, but several other strategies must also be mentioned. They fall into a category you might call “Achilles Hygiene.”

What Athletes Must Know about Achilles Hygiene

Hygiene can be defined as “conditions or practices conducive to maintaining health and preventing disease.” More specifically, Achilles hygiene addresses non-training variables that may increase the risk of Achilles injuries. Here are four:

Risk Factor #1: Wearing Shoes with Elevated Heels

Whether for comfort or because they are fashionable, athletes often wear tennis shoes with elevated heels throughout the day. The elevated heels shorten their Achilles’ range of motion, almost like walking on the balls of your feet all day. For this reason, Gagné says these shoes can predispose an athlete to Achilles injuries and even lead to plantar fasciitis.

A better approach is to wear shoes with elevated heels when your sport requires it, such as with weightlifting, and wear walking shoes or shoes with low heels throughout the day—walking shoes have a lower heel and tend to have better lateral stability.

Risk Factor #2: Dehydration

Dehydration affects the elasticity of the tendons, causing them to behave like old rubber bands that easily snap when stretched. Although hydration is a complex subject beyond the scope of this article, consider that the cells will become dehydrated if there isn’t enough potassium or there’s too much sodium. This is often the case with consuming soft drinks containing high amounts of sodium.

Rather than trying to find a magic water-hydration formula, focus first on avoiding processed foods and high-salt sports drinks that can cause dehydration. Also, try to fulfill most of your water needs by consuming more fruits and vegetables.

Risk Factor #3. Too Much Sitting

Sitting for long periods has been associated with increases in blood sugar and body fat, orthopedic issues, and many other unnatural health conditions. Gagné also believes there is a connection between excessive sitting and Achilles injuries, as it can cause tightness and weakness in the fascia.

“Sitting can affect the function of the cerebrum, the part of the brain that controls muscle movement,” says Gagné. “The result is that kids are less athletic, and their reduced proprioceptive ability further increases their risk of injury.”

Risk Factor #4. Bad Medicine

Some medications prescribed to treat injury, pain, or infections can negatively affect the elasticity of the tendons, leading to rupture. One type of steroid used to relieve pain and reduce inflammation is cortisone, which is prescribed conservatively because it can weaken tendons.

Fluoroquinolones are a class of antibiotics that have recently received some attention as they treat respiratory issues, including COVID-19. That’s the good news. The bad news is that in a paper published in 2002, researchers conclude that these drugs may have “a direct toxic effect on collagen fibers” after just a single dose and “increase the risk of Achilles tendon disorders.”

Let’s add one more to our list—testosterone. Although there are many red flags with performing studies on athletes taking performing-enhancing steroids, we may infer some conclusions based on studies of those taking testosterone replacement therapy (TRT). TRT has become a billion-dollar business regulated by the medical profession, and the data pool is increasingly growing.

A 2023 study in the Journal of Foot and Ankle Research looks at 423,278 subjects, ages 35-75, who were on TRT for at least three consecutive months. The researchers conclude, “There is a significant association between Achilles tendon injury and prescription TRT, with a concomitantly increased rate of undergoing surgical management.” Additional studies have been conducted on biceps and quad tendon injuries with similar results.

Some medications prescribed to treat injury, pain, or infections can negatively affect the elasticity of the tendons, leading to rupture, says Kim Goss. Share on XIt’s not my place to give medical advice—after all, sometimes the best medicine is medicine. However, if athletic performance is a priority, consult your appropriate healthcare providers about any drug’s risks vs. rewards on tendon health and perhaps consider alternatives.

Beyond those four risk factors, other variables include age, hormonal fluctuations during a woman’s menstrual cycle, fatigue, training environment, nutritional deficiencies, equipment/gear quality, and, of course, coaching. That said, addressing these four Achilles hygiene variables is a good start.

Much more work is needed to educate coaches and the athletic population about preventing Achilles injuries. Hopefully, I’ve given you some practical ideas that may help you develop effective strategies to enhance athletic movement and reduce the risk of Achilles injuries.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Siu R, Ling SK, Fung N, Pak N, Yung PS. “Prognosis of elite basketball players after an Achilles tendon rupture.” Asia Pac J Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Technol. 2020 Apr 10;21:5-10.

Earp JE, Newton RU, Cormie P, and Blazevich AJ. “The influence of loading intensity on muscle-tendon unit behavior during maximal knee extensor stretch shortening cycle exercise.” European Journal of Applied Physiology. October 2013.

Gagné, Paul, Personal Conversation, October 6, 2024.

Charniga, Andrew, Jr. “It’s All Connected, Part III: Reverse Engineering Injury Mechanism.” Sportivnypress.com. July 10, 2015.

Goss, Kim. “Practical Steps to Prevent Ankle Injuries: Part 1.” March/April 2006, BFS magazine.

Goss, Kim. “Practical Steps to Prevent Ankle Injuries: Part 2.” May/June 2006, BFS magazine.

Tsatsouline, Pavel, The Naked Warrior, Dragon Door Publications; 1st edition, December 1, 2003.

Charniga, Andrew, Jr. “Ankle Squats.” Sportivnypress.com. February 10, 2024.

Starzynski, Tadeusz and Sozanki, Henryuk. Explosive Power and Jumping Ability for All Sports: Atlas of Exercises, Stadion Pub, July 31, 1999.

Hygiene definition. Oxford Languages, languages.oup.com.

Cronin NJ, Barrett RS, Carty CP. “Long-term use of high-heeled shoes alters the neuromechanics of human walking.” J Appl Physiol (1985).

Valtin H. “Drink at least eight glasses of water a day.” Really? Is there scientific evidence for “8 x 8”? Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002 Nov;283(5):R993-1004.

Daneshmandi H, Choobineh A, Ghaem H, Karimi M. “Adverse Effects of Prolonged Sitting Behavior on the General Health of Office Workers.” J Lifestyle Med. 2017 Jul;7(2):69-75.

Van der Linden PD, Sturkenboom MC, Herings RM, Leufkens HG, Stricker BH. “Fluoroquinolones and risk of Achilles tendon disorders: case-control study.” BMJ. 2002 Jun 1;324(7349):1306-7.

Lareau CR, Hsu AR, and Anderson RB. “Return to play in national football league players after operative Jones fracture treatment.” Foot & Ankle International. 2016 Jan;37(1):8–16.

Albright JA, Lou M, Rebello E, Ge J, Testa EJ, Daniels AH, Arcand M. “Testosterone replacement therapy is associated with increased odds of Achilles tendon injury and subsequent surgery: a matched retrospective analysis.” J Foot Ankle Res. 2023 Nov 11;16(1):76.

Rebello E, Albright JA, Testa EJ, Alsoof D, Daniels AH, Arcand M. “The use of prescription testosterone is associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing a distal biceps tendon injury and subsequently requiring surgical repair.” J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023 Jun;32(6):1254-1261.

Meghani O, Albright JA, Testa EJ, Arcand MA, Daniels AH, Owens BD. “Testosterone Therapy Is Associated With Increased Odds of Quadriceps Tendon Injury.” Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2024 Jan 1;482(1):175-181.