(Lead photo by Linda Brothers, LiftingLife.com.)

On December 12, 2022, Arizona Cardinals quarterback Kyler Murray was scrambling toward a first down when he collapsed awkwardly, tearing his right ACL. What puzzled the sports broadcasters was that no one touched him—it was, to use a term we seem to be hearing more frequently, a “non-contact injury.”

It’s one thing for a quarterback to suffer a severe injury when pounced upon by a 300-pound lineman, but how could Murray sustain a season-ending injury just by zigging when he should have zagged? After all, the NFL supports its athletes with elite strength coaches, state-of-the-art training facilities, and eight-figure annual sports medicine budgets. Let’s look at the bigger picture.

Although the numbers vary according to the sport, about two-thirds of lower body injuries are considered “non-contact.” The rest are considered “contact,” involving a collision with another athlete or an external object. Over the past decade, ACL injuries in the NFL averaged about 50 per year, with slightly more occurring during the season. Further, those with a history of ACL reconstruction are more likely to suffer a subsequent ACL injury.

ACL injuries are bad, but Achilles tendon injuries may be the worst. Complete recovery from an Achilles rupture can take a year and may signal the end of a promising career at the pro level. How about some numbers?

On February 22 of last year, the NFL reported 25 Achilles injuries during the season, and players in the Canadian Football League didn’t fare much better. In a 2021 training camp, four players on the Saskatchewan Roughriders team suffered Achilles tendon tears. These were non-contact injuries, and all four occurred in just six minutes! Grass versus artificial turf debates aside, something wrong is going on—and it’s not just in football.

As with the NFL, NBA superstars enjoy an entourage of support from their strength coaching and sports medicine resources. Still, the NBA’s rate of lower extremity injuries has not decreased significantly in the past dozen years, despite the emphasis on three-point shooting where there is less contact (and that fuels the Jordan vs. LeBron debate!). Consider the Golden State Warriors.

In the 2019 NBA season, many sports commentators believed the Warriors would repeat as champions. However, Kevin Durant pulled a calf muscle, then injured his Achilles; DeMarcus Cousins, who joined the Warriors while on the mend from an Achilles tear, tore his quad and then his ACL; a tender Achilles hampered Andre Iguodala; and after injuring his hamstring, Klay Thompson tore his ACL! And that’s just one team!

Between 1995 and 2007, the NBA reported four Achilles injuries. In 2019, there were six in a single season! Share on XOn a larger scale, between 1995 and 2007, the NBA reported four Achilles injuries. In 2019, there were six—again, in a single season! Adding injury to injury, before the 2021 NBA playoffs, the league’s premier players missed 370 out of 1,944 games. Although a lot of roughhousing occurs during NBA games, basketball is still considered a non-contact sport.

I’ve been focusing on men’s sports. Let’s now take a deep dive into women’s sports.

Risky Business: The Female Knee

A study published in 2021 concluded that “there are approximately 200,000 to 250,000 ACL injuries that occur in the United States annually, a rate that has doubled over the last 20 years; and this rate has been increasing by a rate of 2.5% annually in the United States.”

Breaking these numbers down in terms of gender, researchers have found that “the relative risk of ACL injury in women is 3 to 8 times greater than males.” The numbers for several women’s sports are so bad that many parents forbid their daughters from ever playing them! Unquestionably, the No. 1 sport parents are concerned about is soccer.

One study reviewing 793 articles found that female soccer and basketball players were about three times more likely to tear their ACL than males. Another study suggested that sport skill level was not the primary issue, as it found that female college soccer players were significantly more susceptible than high school players to injuring their ACLs. The question appears to be not if a female will get a non-contact injury from playing soccer but when?

One straightforward solution to reducing injuries is not to specialize in a single sport. In a 2017 study involving 1,544 high-school-age athletes (half female), sports specialization was identified as an independent risk factor for injury. Specifically, the researchers found that lower extremity injury was 85% higher for those athletes who played a single sport year-round. Also, the popularity of triathlons in the ’80s has been partially attributed to the high injury risk associated with those who focused on long-distance running workouts to compete in marathons, an event on just about every recreational runner’s bucket list. Just one problem.

One straightforward solution to reducing injuries is not to specialize in a single sport…but is that the only answer—the best way to reduce injuries in a sport is to stop playing it? Share on XTo refine their skills to perform at the highest levels and better their odds of earning a scholarship, high school athletes often play on non-school sports teams year-round. Further, college coaches rarely allow their athletes to play multiple sports, particularly at the Division I level. But, again, is that the only answer—the best way to reduce injuries in a sport is to stop playing it?

The Weightlifting Paradox

The extent of non-contact injury problems has led many medical experts and sports broadcasters to throw up their hands and say, “Such is the nature of sports!” and “It is what it is.” If so, how come weightlifters rarely get hurt? ACL and Achilles’ injuries are so uncommon in weightlifting that coaches often go their entire careers without seeing either.

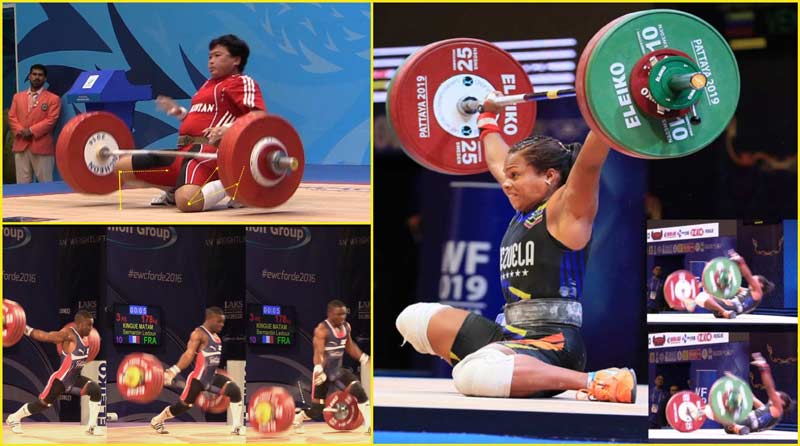

Take a look at the scenes in image three that initially seem, well…horrific. In the top left photo, the female lifter drops nearly 297 pounds across her thighs, slamming her knees against the platform. In the bottom left photo sequence, a 152-pound male lifter drops 392 pounds across his outstretched back leg. In the last photo sequence, an athlete awkwardly loses a snatch overhead, causing the weight to fall on her and twisting her knees and ankles in ways that knees and ankles should not be twisted.

How come weightlifters rarely get hurt? ACL and Achilles’ injuries are so uncommon in weightlifting that coaches often go their entire careers without seeing either of them. Share on X

If you thought the impact of having these massive weights crash on these athletes caused crippling injuries, you would be wrong. All three lifters avoided injury, and such escapes are commonplace in the sport. What’s going on? To find some answers, let’s talk anatomy.

Tendons are not rigid, cable-like structures connecting bones to muscles but can stretch up to 8% of their length. The tendons and ligaments of the foot, ankle, knee, and hip work together as a single biological leg spring. These leg springs can stretch, store energy, and recoil to enhance power. There’s more!

Weightlifting sports scientist Andrew “Bud” Charniga says these tissues possess a “reactive protective mechanism” that immediately responds to unstable and unanticipated conditions by releasing muscle tension rapidly and dissipating and redistributing mechanical energy. This mechanism is active in all sports, enabling quarterbacks to safely zig when they should be zagging. It also works with the upper body.

During an arm wrestling match, when the tension on the opponent with the weaker arm is too high, the arm muscles instantly shut down, and the forearm slams on the table. That’s a good thing. If the weaker opponent continued, muscles and connective tissue could be torn, and bones could be fractured.

Does this reactive protective mechanism work just as effectively in females? Consider the results of a five-year study on 480 women who competed in the week-long European Weightlifting Championships. When you add the training lifts for those who arrived several days before they competed and their competition warm-ups and platform attempts, tens of thousands of maximal and submaximal lifts were performed.

Considering those fragile Q-angles women possess, you would think the medical staff at this competition would have been swamped with injuries and have the European equivalent of 911 on speed dial. However, researchers reported zero hip, thigh, knee, lower limb, or foot injuries. Success leaves clues!

Video 1: Nicole (Patruno) Morales demonstrates the large amplitude, dynamic movements involved in weightlifting that use the elastic properties of the connective tissues. Nicole broke junior New England weightlifting records, and her best official lifts are a 178-pound snatch and a 229-pound clean and jerk.

Now that I’ve got your attention, please be open-minded and consider the following human movement perspective on preventing non-contact ACL and Achilles injuries. It may seem a bit radical because many concepts were introduced a half-century ago, but hear me out.

Non-Contact Injuries, Lies, and Athletic Tape

One popular theory explaining the high number of ACL injuries is poor conditioning. There’s even a name for it: “Exercise Deficit Disorder.”

The term was used in a research paper to explain why some NFL players had an increased risk of ACL injury during the COVID-19 period because they did not display the “enhanced physical prowess and necessary neuromuscular control” to avoid injury. As such, one recommendation I’ve seen to reduce the risk of ACL and Achilles injuries in athletes is boot-camp conditioning drills to prevent excessive fatigue. One college program I’ve read about even hired military personnel dressed in combat fatigues to motivate the athletes.

Other proactive methods that have me scratching my head include movement drills designed to keep an athlete’s ankles, knees, and hips in perfect postural alignment. During one coaches’ meeting, I was presented with some rather odd ACL prevention methods movement for women’s basketball developed by an athletic training group. For example, they said that whenever an athlete jumps for a rebound and grabs the ball, they should drop into a full squat to protect the ACL! Huh?

As for all the unstable “functional” strength training exercises recommended, many seem inspired by Cirque du Soleil and do little but distract athletes from being stronger through conventional methods. I say this because Dr. Michael Jonathan Wahl has extensively researched stability training and found that the brain motor patterns exhibited when performing exercises on unstable surfaces were the same as those on stable surfaces. Dr. Wahl had some strong opinions about the value of unstable exercises in injury prevention during an interview I did with him in 2007:

“Sure, a Swiss ball exercise can be taxing for someone who has never done any exercise before; but get a first-year physics student to explain the disrupted torque on the body that occurs when someone squats 500 pounds, and you’ll see that the entire muscle system has to work tremendously hard to handle that type of weight. When an athlete turns their ankle, it’s often because they are not strong enough to handle the disrupted force of the activity, so why not train to get used to that excessive force using the principle of progressive resistance?”

For women, research has found that during a women’s monthly cycle, hormonal variations weaken the connective tissues, making them more susceptible to injury. The recommendation would be to alter training loads during each phase of the menstrual cycle, but you have to question the practical value of this advice. Are coaches supposed to chart each athlete’s menstrual cycle and pull them out of practices and games due to unacceptable hormone levels?

Then, there are the shoes. Like homeowners with power tools, athletes don’t buy shoes—they invest in shoes. The athletic shoe market is a profitable business, such that considerable funding has been provided for researching footwear to reduce injuries. For example, a study on foot fractures concluded that narrow cleats with minimal stiffness might contribute to fractures of the fifth metatarsal (i.e., Jones fracture). One extensive review concluded that in studying foot injuries, we need to “measure and record the surface properties and potentially the properties (or at least the model) of the footwear worn by study participants.” Good to know.

Canadian weightlifter Francis Luna-Grenier never got the memo. Luna-Grenier competed in the 2008 Olympics in the 152-pound bodyweight class and currently holds all the Canadian records in the 160-pound class. He is shown in video 2 snatching 286 pounds without knee wraps, taped ankles, or a spine-saving weightlifting belt. And in contrast to the high-priced adamantium-laced tennis shoes endorsed by celebrity athletes, Luna-Grenier demonstrates the stability he developed by performing this lift with bare feet!

Video 2: Canadian weightlifter Francis Luna-Grenier demonstrates remarkable strength and stability, snatching 286 pounds in bare feet.

Among the most common ways to prevent ACL and Achilles injuries is to “stabilize” body parts using athletic tape and other forms of bracing, even if those body parts are not injured! On that subject, consider what could be called “The Curious Case of Mac Jones.”

An article published on August 16, 2021, reported that the New England Patriots quarterback wore a brace on his left knee for “protective reasons,” not in response to an injury. Jones told reporters that the knee being braced was the one he plants with, thus the need for extra protection. “I feel good…just want to make sure I keep it safe,” said Jones. In many game-day and practice photos, in addition to the protective brace, Jones also appears to have athletic tape connecting his shoe to his lower ankles (you know, because you can never be too safe).

Fast forward 13 months and the game with the Baltimore Ravens. On one play gone horribly wrong, 307-pound defensive lineman Calais Campbell fell on Jones, causing Jones’ ankle to twist awkwardly. Jones’s stabilized knee and lower ankle were fine, but the collision resulted in a high ankle sprain. Coincidence?

Perhaps Charniga is on to something when he says that restricting the mobility of one joint interferes with the “reactive protective reflexes” of the connective tissues? How can the athlete’s body react to the complexities of moving about the athletic field; be ready to dissipate or otherwise redistribute the mechanical energy of sharp turns, cutting, accelerating, falling and deceleration involved in pursuit and avoiding pursuit with all this stiffness of muscles, ligaments, tendons and joints?” Let’s keep going.

Perhaps Charniga is on to something when he says that restricting the mobility of one joint interferes with the ‘reactive protective reflexes’ of the connective tissues? Share on XStrength coach and posturologist Paul Gagné says one of the problems with athletic tape is that it may interfere with the proprioception of the fascia, which is the connective tissue that runs throughout the body. “The fascia contains mechanoreceptors in the tendons and ligaments that respond to stress. Athletic tape may compromise body awareness and affect the ability of the tendons and ligaments to react to excessive tension.” For example, Gagné says he’s seen many powerlifters squat several hundred pounds over body weight using a thick belt and be just fine “but then screw up their lower back when shoveling their driveway because of a lack of proprioception in their core muscles.” There’s more bad news.

Charniga says that if you immobilize an area on one limb, such as with athletic tape, the imbalance may increase the risk of injuring an area on the other limb. One high-profile example of this issue he gave was the injury history of Miami Dolphins’ quarterback Tua Tagovailoa. On December 1, 2018, Tagovailoa suffered a high ankle sprain to his left ankle that required surgery. On October 19, 2019, he sustained the same injury to his right ankle and required surgery. Lastly, on November 16, 2019, he dislocated his right hip and required surgery. Coincidence?

Athletic tape and knee braces are essential in many situations, such that athletes sometimes couldn’t train or compete without them. On January 21, 2013, Kansas City Chiefs quarterback Patrick Mahomes injured his right ankle in the first quarter of the game against the Jacksonville Jaguars. He hobbled to the sideline to get taped up, then went back out for a few plays. He returned to run a half-dozen plays in the second half before being taken out of the game.

This was the postseason, so apparently, the risk of Mahomes making the injury worse was worth the reward of being one step closer to the Super Bowl. Final score: Kansas City 27, Jacksonville 20. The following week, Mahomes’ ankle was heavily taped in their meeting with Cincinnati. Mahomes was obviously uncomfortable throughout the game, favoring his ankle. But Kansas City kicked the winning field goal in the final seconds, and the Chiefs earned another appearance in the Super Bowl!

Braces and athletic tape, particularly used as a protective measure in non-injured athletes, MAY interfere with the functions of the tendons and ligaments, increasing the risk of injury. Share on XThe takeaway is that braces and athletic tape, particularly used as a protective measure in non-injured athletes, may interfere with the functions of the tendons and ligaments, increasing the risk of injury. This brings us to training.

The Relaxation Response

Gagné has worked with more than 500 NHL players in the past 40 years, pro athletes in several other sports, gold medal Olympians, and our barefoot weightlifter Luna-Grenier. He says we should turn to neuroscience rather than just looking at muscle contractions to prevent injuries.

Jean-Pierre Roll won the highest awards in neuroscience, and Gagné has applied Roll’s research to strength training and injury prevention. “Roll says it’s the eccentric contraction that codes movement. If I’m a baseball player and throw a ball, an eccentric contraction of the long head of the biceps will decelerate my arm and protect my shoulder and elbow joints. Likewise, when kicking a football, the hamstrings are more active than the quads because of their involvement in the deceleration of the leg.”

The success of Louie Simmons and his Westside Barbell Club athletes attests to the value of using bands in training powerlifters. However, Gagné says bands can adversely affect neuromuscular coding because as the bands stretch, their resistance increases, so the antagonist muscles do not need to contract as hard. Charles R. Poliquin would agree.

About 30 years ago, I asked this legendary strength coach about the value of elastic band exercises, which were becoming popular with powerlifters. He told me that when he was hired to work with the Canadian National Synchronized Swimming Team, there was an epidemic of shoulder injuries on the team. When he asked about their strength training program, he learned they use elastic band exercises. He was able to resolve their shoulder injuries simply by eliminating these exercises. From then on, he referred to band training as “tendinitis in a can.” How about one more example?

In the ’70s, many track and field coaches thought they could make runners faster by having them wear ankle and wrist weights during training. It didn’t work and even made some athletes run slower when they stopped using them. What’s more, the weights created momentum in the arms and legs that was challenging to control, affecting the deceleration of the limbs and leading many athletes to complain of overuse injuries.

Legendary track coach Bud Winter’s motto was “Relax and Win!” It’s true. Sports scientist Leonid P. Matveyev has shown that in dynamic sports, muscles contract faster than they relax in novice athletes. However, muscles can relax faster than they contract in elite athletes. Matveyev’s colleague, sports scientist Yuri Verkoshansky, noted that in speed endurance events such as the 400m and 400-meter hurdles, “the key factor defining and regulating sport results at all stages is the speed of muscle relaxation.”

Elastic bands prolong the time an agonist muscle is under tension, which is precisely what you don’t want. Share on XThis brings us back to using bands with barbells. Bands prolong the time an agonist muscle is under tension, which is precisely what you don’t want. Matveyev said the near-isometric methods (often used by strongmen, powerlifters, and bodybuilders) could create “internal tension” that affects the ability of antagonist muscles to function efficiently. Matveyev referred to this condition as “coordination enslavement.”

The takeaway is that weightlifting is one of the most effective ways to prevent non-contact lower-body injuries since it enhances the elastic strength qualities of the connective tissues. What if weightlifting is not an option? Let’s explore some alternatives.

The Fast Eccentrics Solution

If you don’t know how to teach weightlifting or don’t have the equipment or facilities to perform these lifts safely, you have other training methods available. One of these options could be referred to as “fast eccentrics.”

The textbook Supertraining by Verkhoshansky and Mel Siff, Ph.D., was published in 1993. It was here that they introduced a concept they called “the triphasic nature of muscle action.” They said that all athletic movements contain three types of contraction: eccentric, isometric, and concentric. Their message was that knowing the qualities of each type of contraction should influence how strength coaches and personal trainers should design workouts.

I first met Siff in the early ’90s and wrote many articles with him. He expanded on this concept by telling me about the value of performing exercises emphasizing rapid eccentric movements. One such exercise was a large-amplitude squat jump characterized by a fast eccentric motion with a slight bounce out of the bottom: full knee extension is not emphasized, and you only elevate a few inches off the floor (video 3). Note the emphasis on “large amplitude.”

Video 3: Dynamic, large-amplitude squat jumps and assisted split squat jumps enhance the elastic qualities of the connective tissues.

Charniga says performing exercises through a large range of motion is critical to keeping connective tissues healthy (again, the example of injury-free weightlifters). Consider that, in one research study, surgeons who repaired ACL tears found that the tissues being repaired often showed signs of long-term damage before the tear. The damage predisposed the ligament to injury, acting like a frayed, old rubber band that can easily snap. This finding suggests that exercises performed by today’s athletes (such as partial range squats?) may increase the risk of ACL and Achilles tendon tears.

I’ve used many variations of these exercises with my athletes over the years, particularly figure skaters and sprinters. About 14 years ago, I was a volunteer strength coach for a girls’ weight training class at a high school in the Midwest. That first semester, the primary athletes attending were basketball players, and the coach told me she had to spend 45 minutes before every practice taping ankles.

Before the end of the semester, the coach told me she didn’t have to tape anymore, and there were no catastrophic injuries, such as ACL or Achilles injuries. This was not a scientific study (and the data could be dismissed as N=1), but again, success leaves clues! Oh, I should also mention that within a year, the class had 12 girls clean 135 pounds and nine girls vertical jump over 23 inches.

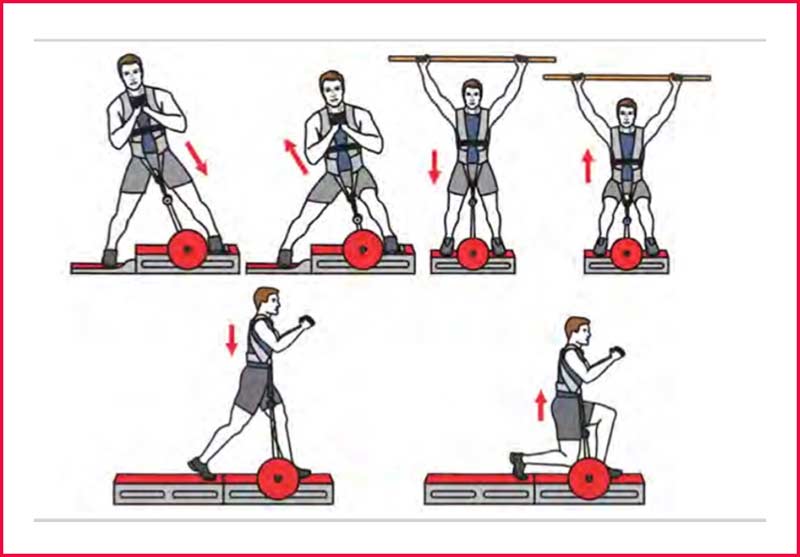

Besides weightlifting and unique jump exercises, iso-inertial training using flywheel devices is another way to injury-proof the body. Share on XNow let’s see what modern technology has to offer. Besides weightlifting and unique jump exercises, iso-inertial training using flywheel devices is another way to injury-proof the body.

Gagné has used iso-inertial training with pro hockey players and elite athletes in other sports for more than a dozen years. Among his success stories are the three Dufour-Lapointe sisters who compete in mogul skiing. In 2014, Justine won Olympic gold, Chloe won silver, and Maxime joined them as an Olympian. Gagné has been their only strength coach and has used iso-inertial training with these remarkable athletes since he started with them.

Gagné says iso-inertial devices enable athletes to perform numerous resistance exercises at high speeds during the concentric (muscle shortening) and eccentric (muscle lengthening) phases. “The goal is not only to increase force production but to enable the muscles to contract and decelerate faster,” says Gagné. “Being able to decelerate faster enables the athlete to change direction faster.” Consider sprinting.

One component of running speed is ground contact time—the less time athletes spend on the ground, the faster they go. Iso-inertial training enables athletes to flex and extend their legs and ankles faster, reducing ground contact time so that the athlete covers more ground with each step.

“This is why iso-inertial training is so good,” says Gagné. “The flywheel forces you to transition quickly between concentric and eccentric muscular contractions, which is the key in any sport. It’s not at the top of a movement when you want to produce the most force; deceleration occurs in sports at the top of the movement, where injury happens. At the bottom of a movement, a stretch reflex will help get you out.” Gagné added that iso-inertial training complements weightlifting, and he used it when he trained Luna-Grenier.

As a bonus, because iso-inertial training focuses on the dynamic properties of the connective tissues, it will result in little or no soreness. “Slow, eccentric training is most responsible for muscle soreness,” says Gagné. “If you were to slowly walk down several long, high hills the next day, you might experience a high level of soreness. Iso-inertial training involves fast eccentric movements, utilizing the elastic components of the tissues, so post-workout soreness is rare. Likewise with weightlifters—rarely have I ever heard of weightlifters complaining of muscle soreness.”

Because iso-inertial training focuses on the dynamic properties of the connective tissues, it will result in little or no soreness. The lack of muscle soreness has significance for program design. Share on XThe lack of muscle soreness has significance for program design, particularly in-season training. How often have sports coaches, particularly sprint and jump coaches, forgone any resistance training in-season because they feared their athletes getting sore? The result is that athletes make minimal gains in strength during the year, as much of their training is regaining the strength they lost from these in-season “maintenance” phases. Thus, the strength coach is happy to train athletes harder in the weight room, and the sports coach is happy because their athletes are not sore going into practices or competitions. It’s a win-win!

To summarize, here are six key points I want you to take away from this article:

- The continued high rates of non-contact ACL and Achilles injuries suggest that many training methods to prevent these injuries are ineffective.

- The risk of ACL injuries in women due to structural and hormonal differences may be exaggerated.

- Athletic tape and bracing have their place in sports performance. However, if used as a preventive method in non-injured athletes, they may increase the risk of ACL and Achilles injuries.

- The ability to relax muscles quickly is a critical component of athletic performance and injury prevention.

- Weightlifting and fast eccentric exercises may reduce ACL and Achilles injuries by enabling athletes to better deal with excessive stress and unstable conditions.

- Fast eccentric training enables athletes to increase power production without experiencing high levels of muscle soreness.

Can the ideas I shared with you guarantee that an athlete will never tear an ACL or Achilles tendon? Of course not. However, when you train the body how it was meant to move and perform, there is a good chance that “non-contact injury” may no longer be part of your vocabulary!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine. “Sports specialization may lead to more lower extremity injuries.” ScienceDaily, July 23, 2017.

Anderson FC and Pandy MG. “Storage and Utilization of Elastic Strain Energy During Jumping.” Journal of Biomechanics. 1993;26(12):1413–1427.

Charniga A. “Part II: Practical Solutions to the Problem of Achilles Rupture and the Proliferation of Injuries to the Lower Extremities of Football Players,” Feb 14, 2017; “Of Flat Tires’ & Brittle Basketball Players,” Jul 24, 2019; “The ‘Derivatives’ Myth,” Jan 5, 2022; “A Stability/Instability Convexity,” April 23, 2021; “Hamstring Injury: Prophylaxis in Sport,” June 29, 2021; “Hamstring Injury in Sport,” July 21, 2021; “Why? So Many Flies Keep Dropping in The NFL’s Barbecue,” Feb 15, 2022; “Tree Stump Training & Initials: Mechanisms of Injury Susceptibility, Part 1,” April 11, 2022; “Tree Stump Training & Initials: Mechanisms of Injury Susceptibility, Part II,” May 1, 2022; “The Secret to the Weightlifter’s Strength: Speed of Muscle Relaxation,” Jan 30, 2023. Sportivnypress.com

Chen J, Kim J, Shao W, et al. “An Anterior Cruciate Ligament Failure Mechanism.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2019;47(9):2067–2076.

Gagné P. Personal Communication, Dec 2022.

Gornitzky AL, Lott A, Yellin JL, Fabricant PD, Lawrence JT, and Ganley TJ. “Sport-Specific Yearly Risk and Incidence of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears in High School Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2016;44(10):2716–2723.

Goss K. “The Case Against Stability Training.” Bigger Faster Stronger, March/April 1007, p. 70–73.

Hartmann H, Wirth K, and Klusemann M. “Analysis of the Load On the Knee Joint and Vertebral Column with Changes in Squatting Depth and Weight Load.” Sports Medicine, 2013;43(10):993–1008.

Hewett TE. “Neuromuscular and Hormonal Factors Associated with Knee Injuries in Female Athletes.” Sports Medicine. 2000;29(5):313–327.

Hoffman JR, Cooper J, Wendell M, and Kang J. “Comparison of Olympic vs. traditional power lifting training program in football players.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2004; 18(1):129–135.

Hsu AR and Anderson RB. “Foot and Ankle Injuries in American Football.” American Journal of Orthopedics. 2016;45(6):358–367.

Lareau CR, Hsu AR, and Anderson RB. “Return to play in national football league players after operative Jones fracture treatment.” Foot & Ankle International. 2016 Jan;37(1):8–16.

Lyons T, Dynamic Fitness Equipment, Personal Communication, January 2023.

Matveyev LP. Fundamentals of Sport Training, FIS, Moscow, 1977.

McBride JM, Triplett-McBride T, Davie A, and Newton RU. “A comparison of strength and power characteristics between power lifters, Olympic lifters, and sprinters.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 1999;13(1):58–66.

McDaniel LW, Rasche A, Gaudet L, and Jackson A. “Reducing the Risk of ACL Injury in Female Athletes.” Contemporary Issues in Education Research. 2010;3(3):15–20.

Meijer JP, Jaspers RT, Rittweger J, et al. “Single Muscle Fibre Contractile Properties Differ Between Body‐Builders, Power Athletes and Control Subjects.” Experimental Physiology. 2015;100(11):1331–1341.

Montalvo AM, Schneider DK, Yut L, et al. “What’s my risk of sustaining an ACL injury while playing sports? A systematic review with meta-analysis.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2019 Aug;53(16):1003–1012.

Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Cherny CE, Heidt RS Jr., and Hewett TE. “Did the NFL Lockout Expose the Achilles Heel of Competitive Sports?” Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2011;41(10):702–705.

Prodromos CC, Han Y, Rogowski J, Joyce B, and Shi K. “A meta-analysis of the Incidence of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears as a Function of Gender, Sport, and a Knee Injury–Reduction Regimen.” Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2007;23(12):1320–1325.

Siff, MC. and Verkhoshansky, YN. “The Triphasic Nature of Muscle Action.” Supertraining, 4th edition 1999 (1st edition 1993), p. 53–54.

Silvers-Granelli H. “Why do Female Athletes Injure Their ACL’s More Frequently? What can we do to mitigate their risk?” International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2021 Aug 1;16(4):971–977.

Verkhoshansky, YV., Fundamentals of the Special Physical Preparation of Athletes, Moscow: Fizkultura I Sport, 16:1988. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr., Sportivny Press

Wannop JW, Madden R, and Stefanyshyn DJ. “Footwear, traction, and the risk of athletic injury.” Lower Extremity Review. Jan 2016.

Williams C. “Mac Jones has started wearing a knee brace for ‘protective reasons.’”

August 16, 2021, NBC Sports