By Gabriel Mvumvure and Kim Goss

“You can never be too strong!”

General George S. Patton, Jr., said this 78 years ago, in his paper “Instructions to the Third United States Army,” and it’s a motto many strength coaches endorse. But it may not be a wise approach to help athletes sprint faster or jump higher, at least when it comes to squats. Here’s a better catchphrase:

“I don’t care how much you can squat—I want to know how much you can squat in one second!”

(Lead Photo by Ryan Paiva, LiftingLife.com)

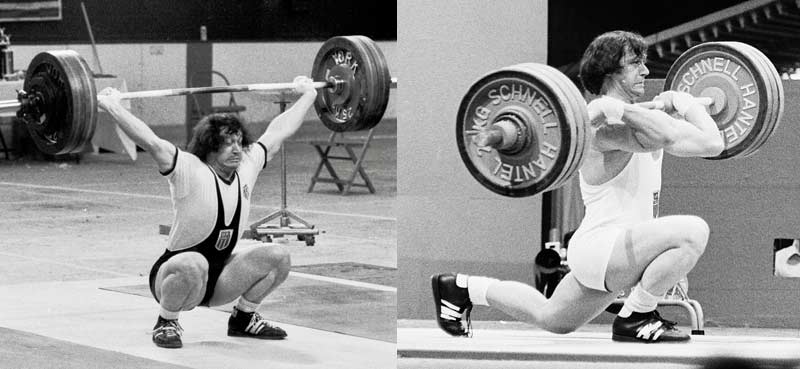

This approach to squatting is championed by Jim Napier, a two-time national weightlifting champion who competed in the 1977 and 1978 World Weightlifting Championships. He broke four American records, including a 314-pound snatch at 165 pounds body weight and a 341-pound snatch at 181 pounds body weight (figure 1).

Besides competing at an elite level, Napier did extensive research on the relationship between barbell velocity and weightlifting performance, including studying the training of hundreds of athletes. Napier summarized his findings in his three books, The Sport of Weightlifting Series.

Jim Napier determined that for the back squat to transfer to the competition lifts (snatch and clean and jerk), the optimal speed during the ascent should be 1 second or less. Share on XNapier determined that for the back squat to transfer to the competition lifts (snatch and clean and jerk), the optimal speed during the ascent should be one second or less (video 1). If it takes longer than one second to rise from the bottom position, and the athlete decelerates through the sticking point, Napier says there is less transfer to explosive strength.

Video 1: Brown University hurdler Brooke Ury measuring bar speed while squatting with a velocity-based testing device.

Before getting into the research supporting Napier’s training methods, let’s look at how to judge the effectiveness of a strength program for athletes with performance testing.

Drat, Not Testing Again!

The bottom line in track and field is what athletes can do in competition, not in the gym. However, between competitions, performance testing can provide valuable feedback about the effectiveness of an athlete’s physical preparation.

At Brown, our performance tests for sprinters include five types of vertical jumps, two horizontal jumps (standing broad jump and standing triple jump), two medicine ball throws (underhand and behind-the-back), and two sprints (10-meter fly and 30-meter acceleration).

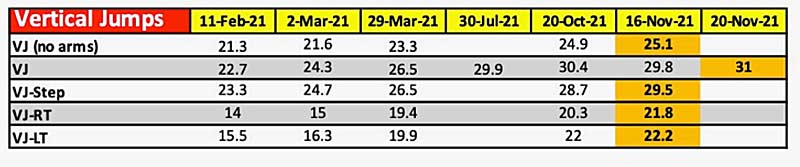

Figure 2 shows the vertical jump profile of Brooke Ury, a sophomore hurdler and sprinter at Brown. It starts with her first test in February (COVID-19 prevented previous tests) and ends with her most recent test in November. Note that her vertical jump (no step) improved from 22.7 inches to 31 inches during this period.

Each test gives us valuable feedback about what our athletes need to focus on to perform their best. However, because it can take a complete training session to perform our entire battery of tests, we often will just administer a single test as a “spot check.” You’ll see that on the seven testing dates of Ury’s report: twice we tested only the vertical jump (arms with no step).

In addition to individual assessments, these tests collectively tell us how well our program is working. For example, since last February, five of our 14 female sprinters improved their vertical jump by an average of 6.34 inches, which is significant since their average starting result was already exceptional at 22.4 inches. As for absolute numbers, we had three female sprinters jump at least 31 inches (no step), and three male sprinters jump at least 37 inches (no step). Much of their training during the off-season was focused on weightlifting movements, especially the clean (video 2) and fast, full squats.

Video 2. Brown University female sprinters showing solid technique in the clean.

Why our interest in vertical jumping? One of the essential characteristics of elite sprinters is they can apply high levels of force into the ground. The more force applied to the ground, the greater the distance covered with each step. Let’s look at the best of the best.

Using data from a race Usain Bolt ran in Monaco in 2011, SMU researcher Andrew Udofa, Ph.D., determined that Bolt could apply 1,080 pounds of force into the ground with his right leg and 955 pounds with his left. Such power enabled the Jamaican Olympic champion to cover the 100 meters in 40.92 steps and run 9.58 seconds in 2009. Compare these results to Carl Lewis, who needed 43 steps to run his world record of 9.86 seconds in 1991.

Knowing the importance of power in athletic performance and ways to measure it, how significant is squatting in developing power and how much should the lift be emphasized in a workout? Let’s find out.

Crunching the Numbers

To help plan their training, weightlifting coaches have developed ratios of the competition lifts to assistance exercises. Using a “performance calculator” developed by the Queensland Weightlifting Association, here are their ratios for the back squat to the clean and jerk:

C&J* Back Squat

154 200

193 250

232 300

270 350

309 400

*weight in pounds

Using this formula, if a weightlifter clean and jerks 154 pounds but squats 300, they need to focus less on leg strength and more on technique.

Although a good starting point for beginners, these ratios may not apply to elite weightlifters or athletes in other sports. Specifically, the squats in most of these formulas are often too heavy, and the results of many of the strongest weightlifters confirm this opinion.

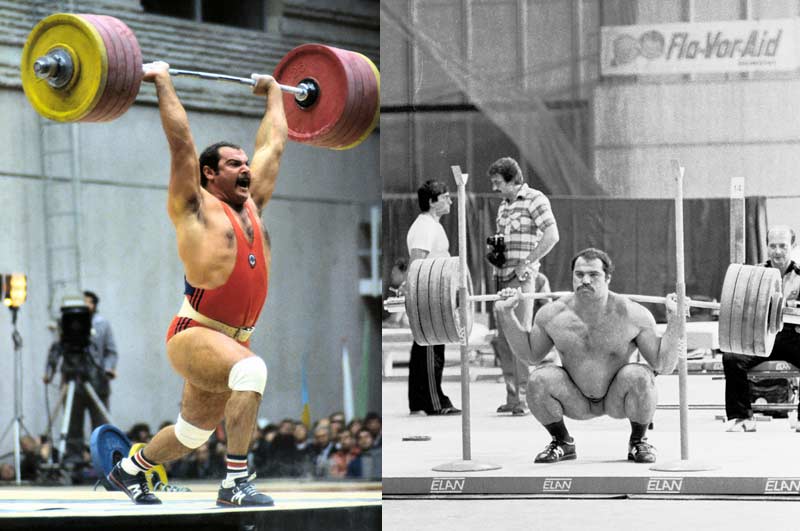

Consider the accomplishments of three weightlifters who broke the absolute world record in the clean and jerk: super heavyweights Vasily Alexeev (564 pounds, 1977) and Anatoly Pisarenko (584, 1984) from Russia, and 207-pound lifter Simon Kolecki (512, 2000) from Poland (figures 3 and 4).

These results suggest these lifters did not become the best in the world DESPITE not squatting heavy but BECAUSE they did not squat heavy! Share on XIn 1970, Alexeev broke the 500-pound barrier in the clean and jerk, and seven years later, he did 64 pounds more. Alexeev said he never used more than 595 pounds in the squat. Pisarenko, who claimed he cleaned 617 in training, says he could only squat 639, and there is little reason to doubt him. His teammate, two-time Olympic gold medalist Aleksandr Kurolovich, saw Pisarenko miss a 573 back squat in training but clean and jerk it just five days later! As for the lighter Kolecki, his best back squat was 518, only six pounds more than his clean and jerk!

Using the Queensland performance calculator, Alexeev should have clean and jerked 459, not 564; Pisarenko 493, not 584 (and certainly not a 617 clean!); and Kolecki 399, not 512. These results suggest these lifters did not become the best in the world despite not squatting heavy but because they did not squat heavy!

Of course, weightlifters need to perform squats in training to rise out of the low catch position with heavy weights in the snatch and clean and jerk. However, there is little value in squatting with weights that far exceed what an athlete can lift in the clean and jerk.

There is little value in squatting with weights that far exceed what an athlete can lift in the clean and jerk. Share on XSports scientist Bud Charniga has extensively studied the research of Russian sports scientists, including translating the works of Yuri “The Father of Plyometrics” Verkhoshansky. Charniga says their research confirms that overemphasizing the squat results in “a point of diminishing returns” and such training “could have the opposite of the desired effect from training which would result in making the lifter slower in the ‘explosion’ phase.” In fact, many elite weightlifters have squatted monstrous weights but had relatively low clean and jerks.

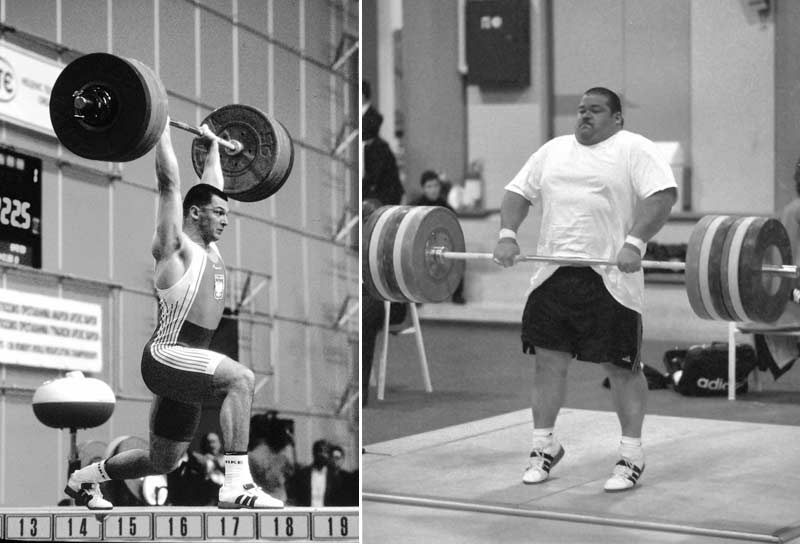

Not to take away from the accomplishments of these U.S. Olympians, but consider the lifting ratios of super heavyweight weightlifters Paul Anderson, Shane Hamman (figure 4), and Mark Henry. Anderson reportedly squatted 1,206 pounds, Hamman officially squatted 1,008 pounds, and Henry officially lifted 953. Anderson’s best clean and jerk was 440, Henry’s was 485, and Hamman’s was 523. Using the Queensland performance calculator, a 1,206 squat equals a 931 clean and jerk, 1,008 pounds equals 778, and 953 equals 736. The current world record is 588.

The Issue Is the Tissue

Sprint and jump coaches who are anti-weight training often don’t recognize the differences among the types of weight training. They seem to believe that all weight training programs will result in athletes becoming slower and significantly bigger, which is simply not true.

Sprint and jump coaches who are anti-weight training often don’t recognize the differences among the types of weight training. Share on XAn athlete can lift weights to dramatically increase their explosive strength with minimal increases in muscle bulk. Elite weightlifters often compete in the same bodyweight classes for many years, sometimes more than a decade, while continuing to increase how much they lift. In 1978, Russia’s Yuri Vardanyan clean and jerked a world record of 462, weighing 181 pounds; six years later, he clean and jerked 493 pounds at the same body weight (figure 5). He also reportedly high jumped 7 feet using a three-step approach and forward takeoff. As for his squatting ability, when he made that 493 record, his best front squat was only 14 pounds more, at 507. Noted weightlifting journalist Seb Ostrowicz said that Yuri “believed that grinding should not be allowed and valued speed in the squat over anything else.”

The takeaway is that just as you wouldn’t have a sprinter perform 3-mile runs (even though both activities are considered “running”), you wouldn’t have a sprinter or jumper use the training methods of the current Mr. Olympia. Let’s take a deeper dive into this subject.

Depending upon the federation they compete in, powerlifters usually squat to a position where their upper thighs are parallel to the floor, not all the way down as weightlifters do. Powerlifters often lean forward more than weightlifters as they descend to their low position, and they perform their lifts relatively slowly to enable them to use maximum weights. In contrast, weightlifters squat quickly and throughout a full range of motion, often bouncing out of the bottom position (figure 6). Such training influences the type of muscle fibers developed and the amount of muscle mass gained.

There are two general categories of muscle fibers, slow-twitch (type I) and fast-twitch (type II). Slow-twitch fibers have more endurance than fast-twitch fibers, but fast-twitch fibers can contract harder. Thus, sprinting and jumping would develop the fast-twitch fibers and distance running the slow-twitch (figure 7).

The type II fibers can be further broken down into IIa, IIb, and IIx. Type IIx fibers are the fastest and enable weightlifters to “generate high forces in rapid time-frames” (Serrano, 2019). How do weightlifters compare to powerlifters and bodybuilders?

First, consider that intensity is the amount of weight used in relation to 1-repetition maximum. Powerlifters and weightlifters train at much higher intensities than bodybuilders, and as such, have more fast-twitch fibers. Next, weightlifters possess more fast-twitch fibers than powerlifters and appear to possess more type IIx fibers. This difference is apparent in the jumping and sprinting abilities of these two types of athletes.

In a 1999 study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (McBride et al.), powerlifters and weightlifters performed three types of vertical jumps. The jumps measured were bodyweight only, jumping with 44 pounds, and jumping with 88 pounds. You might think the powerlifters would excel in the jumps performed with resistance, but the weightlifters were superior in all three tests. Thus, although the word “power” is in the name of their sport, this research suggests that weightlifters are more powerful than powerlifters.

Although the word ‘power’ is in the name of their sport, this research suggests that weightlifters are more powerful than powerlifters. Share on X

The type of muscles activated during activities influences athletic performance, but there’s another type of tissue to consider: fascia.

One strength coach who has done considerable real-world research on how fascia influences performance in elite athletes is Paul Gagné, a Canadian strength coach and posturologist. “Think of fascia as the inner skin of the body,” says Gagné. “It’s tissue that connects and shapes every muscle, organ, blood vessel, and nerve. A tendon is a type of fascia. What athletes and their coaches must understand is that fascia envelops and intertwines with muscle fibers and therefore plays an important role in producing movement.”

Whereas muscles contract and relax to produce movement, Gagné says fascia can stretch and recoil, acting as biological springs to assist the muscles in producing more powerful movements. “Using fast eccentric contractions decreases the time it takes the fascia to stretch and recoil. In effect, the fascia becomes more intelligent, and this intelligence has specific applications to sprinting, jumping, and throwing.”

“Another advantage of fast eccentrics is it focuses on training the fascia and not the muscles, so athletes will not experience the soreness associated with conventional training,” says Gagné. “What I’ve found is that this difference has implications on an athlete’s sports-specific practice. For example, it would not be wise to do slow eccentric squats on a Monday that create high levels of soreness and come to practice on Tuesday and perform maximal sprints. In contrast, I’ve been able to perform challenging fast eccentric workouts using flywheel devices without experiencing soreness the next day.”

The Speed Squat Solution

One way to ensure that they are not squatting too slow would be to regularly assess an athlete’s squatting performance with velocity-based training devices. If the movement speed is more than one second during the ascent of the squat, the weight is too heavy.

One way to ensure they aren’t squatting too slow is to regularly assess squatting performance with VBT devices. If movement speed is >1 sec. during the squat’s ascent, the weight is too heavy. Share on XWhen you are not using a velocity-based training device, base your squatting percentages on what you can perform in the clean. One practical recommendation is to avoid using more than 10%–15% of your best clean (although the top end of this range would be slightly higher with a power clean, as less weight is used). In fact, many elite weightlifters can’t tell you what they can squat because they never go to a maximum, as there is no reason to subject the spine to the additional loading with heavier squats.

Using these conservative guidelines, if an athlete can clean 200 pounds, their optimal squatting weight might be 220–230 pounds, performed for low repetitions (generally three, as higher reps recruit fewer fast-twitch fibers). Thus, the working sets for a “heavy” squat workout might be 210 x 3×3. If the squat is based on a power clean maximum, the range would be higher, so a workout of perhaps 220 x 3×3 would be more appropriate. For more precise recommendations, invest in Napier’s books, as he covers this topic extensively.

“If it looks right, it flies right!” is a popular expression among sprint coaches. Watch a powerlifting competition in which you’ll see athletes slowly grinding out a partial squat. Impressive—especially with the enormous poundages used by today’s elite lifters—but does it look athletic? Compared to the fast, full-range squats of weightlifters, we don’t think so. As General Patton might say, “Train the way you are going to fight!”

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Kim Goss has a master’s degree in human movement and is a volunteer assistant track coach at Brown University. He is a former strength coach for the U.S. Air Force Academy and was an editor at Runner’s World Publications. Along with Paul Gagné, Goss is the co-author of Get Stronger, Not Bigger! This book examines the use of relative and elastic strength training methods to develop physical superiority for women. It is available through Amazon.com.

Kim Goss has a master’s degree in human movement and is a volunteer assistant track coach at Brown University. He is a former strength coach for the U.S. Air Force Academy and was an editor at Runner’s World Publications. Along with Paul Gagné, Goss is the co-author of Get Stronger, Not Bigger! This book examines the use of relative and elastic strength training methods to develop physical superiority for women. It is available through Amazon.com.

References

Napier, J. The Sport of Weightlifting Series: Books 1-3. 2017. www.strengthandvelocity.com. (One-second squat reference: Book 3: Training Manual, pages 30–31.)

Longman, J. “Something Strange in Usain Bolt’s stride.” New York Times. July 20, 2017.

Queensland Weightlifting Federation Performance Calculator: www/qwamembers.org/PerformanceCalc

Charniga, B. “Concerning the ‘Russian Squat Routine.’” Sportivnypress.com, February 8, 2018. [First published, 2001]

Charniga, B. “The Relative Value of the Back Squat in the Training of Weightlifters,” Sportivnypress.com, February 8, 2018. [First published, 2001]

Ostrowicz, S. “In Memory of Yurik Vardanyan,” Weightlifting House, weightliftinghouse.com. [Note: The athlete’s full name is Yuri Norayrovich Vardanyan, but in translations, the spelling “Yurik” has been used.]

Serrano, N., Colenso-Semple, L.M., Lazauskus, K.K., et al. “Extraordinary fast-twitch fiber abundance in elite weightlifters.” PLOS ONE. 2019;14(3):e0207975.

Meijer, J. “Single muscle fibre contractile properties differ between body-builders, power athletes and control subjects.” Experimental Physiology. 2015;100(11):1331–1341.

Fry, A., Schilling, B.K., Staron, R.S., Hagerman, F.C., Hikida, R.S., and Thrush, J.T. “Muscle Fiber Characteristics and Performance Correlates of Male Olympic-Style Weightlifters.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2003;17(4):746–754.

Mcbride, J.M., Triplett-Mcbride, T., David, A., and Newton, R.U. “A Comparison of Strength and Power Characteristics Between Power Lifters, Olympic Lifters, and Sprinters.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 1999;13(1):58–66.

Thank you for this article. It is very thoughtful and has me considering the opportunities this line of training offers for overall athleticism, functional strength, and safety.

Hi Coach

How many sets and reps with power cleans and squat during a weekly workout

Our primary exercise is the full clean, not a power clean. The power clean is harder on the knees and is not as effective for training elastic strength. Also, for beginners, focusing on the power clean first may result in bad habits, as they can often lift more with poor technique (such as by catching the bar with a hyper-wide stance and rounding the upper back). A full clean motivates the athletes to focus on technique because the better the technique, the more they can lift.

But to answer your question, the reps and sets depend on the time of the year. In the summer, for example, a typical clean workout might consist of 8-10 sets of 1-2 reps. Three days before a meet, we might do 5-6 sets of 1-3 reps and do power cleans or power snatches.

For the squat, there is little reason to go for 1-rep maxes. In the summer, a typical squat workout might be 6-8 sets of 3-5 reps. Three days before a meet, the protocol might be 3-5 sets of 3-5 reps.

As an athlete progresses through the program, we will introduce more variety into the program. For example, perform a clean and then immediately do 1-2 front squats. Or do a clean and push jerk. Or do cluster training, which enables the athletes to do more work at a higher intensity.

Consider that during a season, the volume and intensity of sprinting increases. If you add something, you have to something away. However, you can still get stronger by cutting the volume of training but still performing higher intensity workouts.

Hope this helps.

Kim Goss

Thanks coach

did you guys started with light or heavy weights in the full cleans and squats

We take an individualized approach, as some athletes may not have performed these exercises through a full range of motion. For them, flexibility of the ankles has to be addressed (and weightlifting shoes help tremendously!). Also, if an athlete has only performed partial squats, they will be relatively weak in the bottom position, so much lighter weights will have to be used.

I’ve addressed the problems with partial movements in my article, “The Case Against the Hang Power Clean.”

Thank you,

Kim Goss

Hi Coach

I am very interested in the study you guys did at Brown to increase VJ. I am currently a track coach in New Orleans and would like to know the exercise done

Thanks

Hi Coach, loved this article. I have read it a few times. When you do the fast eccentric squats, are you having the athlete attempt to explode up concentrically or just having them complete the lift?

Also, are doing the clean work outs and the squat workouts in the same workout? In the offseason, are the doing these lifts two or three times a week?

Thanks again!

Brian,

You want to rise out of the bottom as fast as possible.

Yes, cleans and squats are performed in the same workout, but at different intensities.

As a general answer, the lifts are performed three times a week for the sprinters. However, sometimes we perform alternatives to the squat.

Hope this helps.

Kim