Cody sits down with Mark Hoover and recaps the experience they had at the 2021 NHSSCA National Conference in Minneapolis, Minnesota. This was the first time to get back in person for the organization and it was an awesome experience.

Key Points for the Conference Include:

– Multiple friendships

– Concentrated lecture and hands-on periods

– Partner Mini-Sessions where vendors display their products to everyone

– ALL THE FOOD

– Multi-Thousand dollar raffle give-away

– Prestigious Award Ceremony

Also, Cody sits down with Rich Burnett LIVE at the Simplifaster booth at the conference to discuss his new unbelievable product, the Plyomat.

Time Stamps

Mark Hoover: 0:00–48:14

Rich Burnett: 48:15-End

Connect with Cody, Mark, and Rich:

Cody’s Media:

Twitter/Instagram: @clh_strength

Mark’s Media:

Twitter: @YorkStrength17

Rich’s Media:

Instagram: @coachb89

Twitter: @CoachRichB

Website: www.plyomat.net

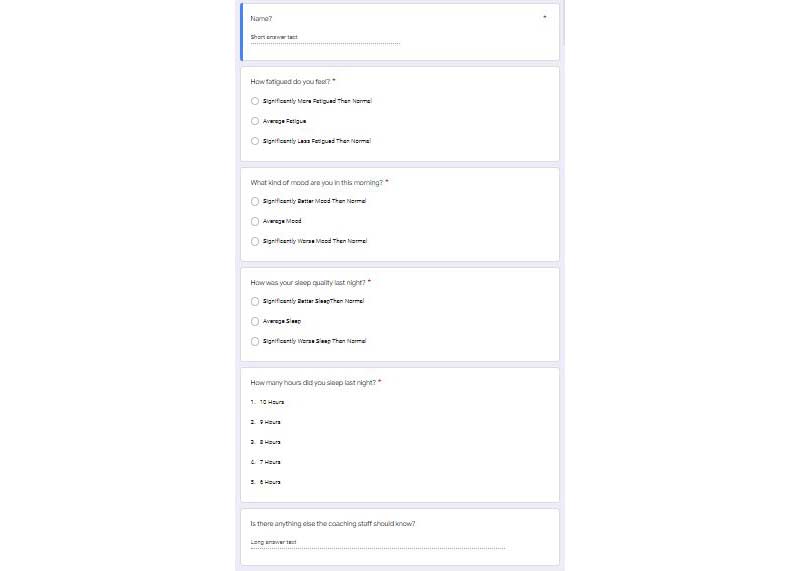

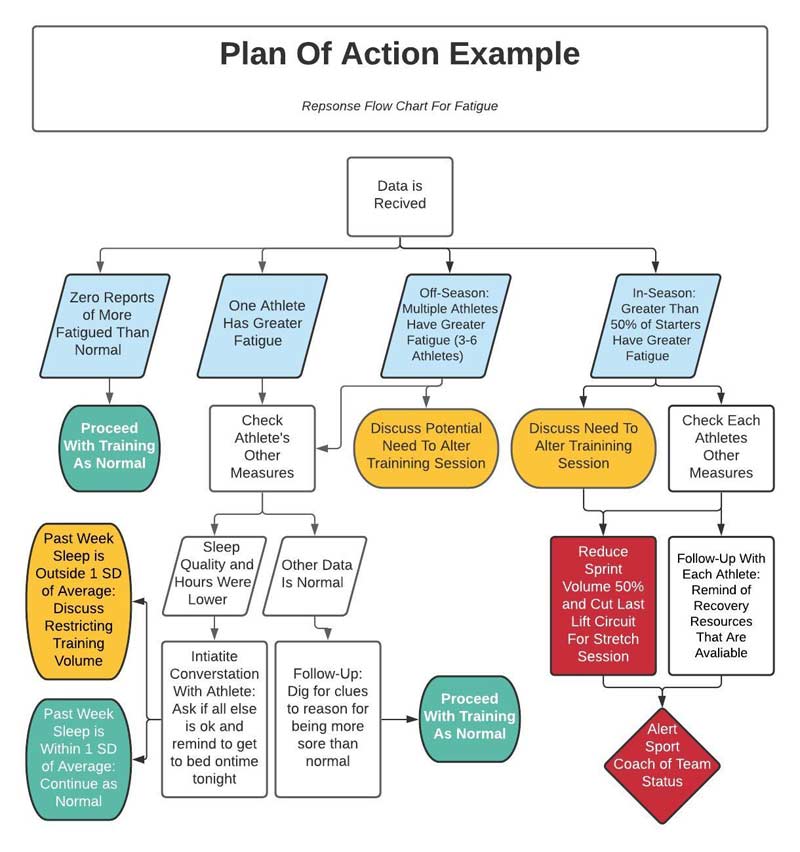

Matt Tometz is a sports performance specialist/sport science coordinator at TCBoost Sports Performance in Northbrook, Illinois. With a speed development background and a fascination for data, it’s his daily challenge to combine the art of coaching with the science of data for his athletes of all ages and sports. Outside the facility, Matt creates educational content for coaches and professionals. Find him on Instagram and Twitter @CoachBigToe, his website www.MattTometz.com, his YouTube channel and LinkedIn “Matt Tometz,” and his email:

Matt Tometz is a sports performance specialist/sport science coordinator at TCBoost Sports Performance in Northbrook, Illinois. With a speed development background and a fascination for data, it’s his daily challenge to combine the art of coaching with the science of data for his athletes of all ages and sports. Outside the facility, Matt creates educational content for coaches and professionals. Find him on Instagram and Twitter @CoachBigToe, his website www.MattTometz.com, his YouTube channel and LinkedIn “Matt Tometz,” and his email: