In competitive sports, athletes rarely perform well when they’re sick, injured, or excessively tired. That’s why, to optimize performance, coaches must design programs that not only allow athletes to train at high training loads but also implement workload optimization strategies to reduce the negative effects of intensive training–illnesses and injuries. Finding and maintaining the delicate balance between training and competition loads, and recovery and rest (i.e., workload management) is both art and science.

It’s also a continuous process that usually requires four elements:

- Daily monitoring of at least a measure of the work done by the athlete (external load)–time, distance, etc.

- The athlete’s response to the work done (internal load)–rate of perceived exertion (RPE), enjoyment, etc.

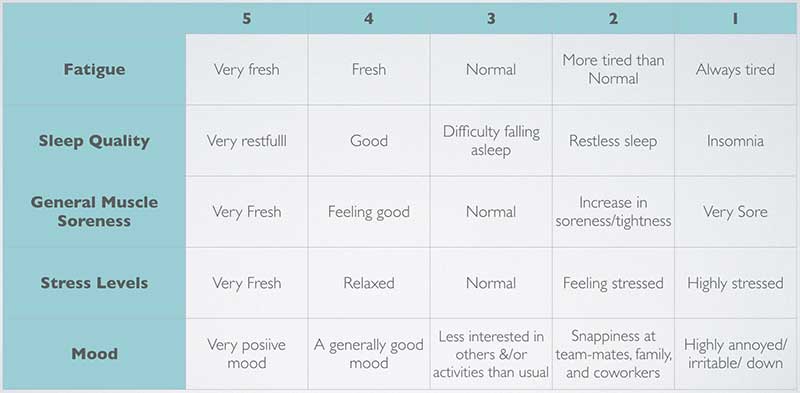

- Tracking of subjective wellness measures–fatigue, quality of sleep, stress, and mood.

- Using these measures and related metrics to adjust the athlete’s training program, recovery, and rest.

While the data collection and workload management process is quite simple, interpreting the data and making coaching decisions based on this information can be tricky. This article presents the most common load management mistakes and provides solutions to fix them.

Athletes Are Not Adequately Prepared to Sustain the Imposed Load

Athletes often get injured in the last part of a game, see their performance drop during multi-day events, make technical or tactical errors at the end of a competitive event, or catch the flu at the end of an intensive training camp.

Most of the time, these issues are predictable. They occur because athletes are not adequately prepared for the physical and psychological demands imposed by the training or competitive task.3, 4 This lack of readiness produces excessive fatigue, which in turn, reduces motor control, impairs concentration, and makes the athlete more vulnerable to injuries and infections.2, 4, 5

Solution

- Accurately assess the training or competition task and identify the key performance indicators (KPIs). KPIs are both objective (how many sprints, how many throws, magnitude, and duration of power output, etc.) and subjective (what the athlete finds the hardest to do during the targeted event).

- Administer KPI-specific tests to compare the athlete’s current level of fitness and performance to the task requirements. Progressively increase the athlete’s performance capacity to the level required by both the overall competitive task and specific KPIs.

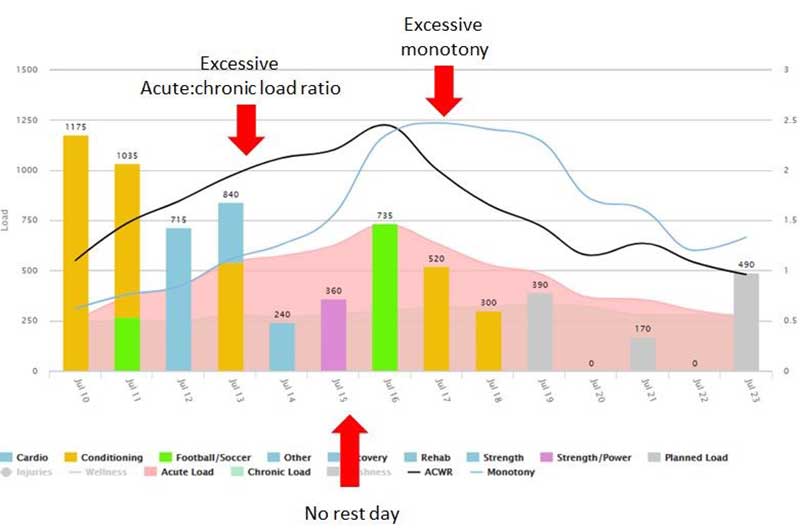

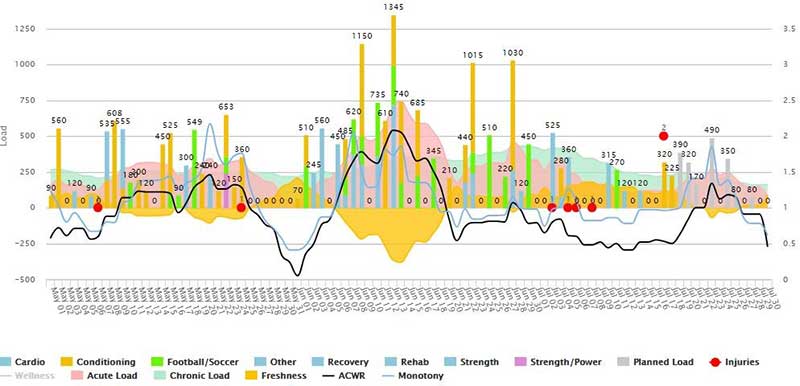

- Monitor the Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio carefully for both internal and external load (1-2 key sport-specific metrics) and keep it in the 0.8-1.3 range.2 A ratio higher than 1.3 indicates the athlete’s weekly load is more than what they’re prepared for and will significantly increase their risk of injury and illness.

Workload Is Increased Too Quickly

A fast increase in workload is a major risk factor for injury and often happens in two situations:

- Athletes return to the sport after an injury.

- Athletes return to full training after a long period of inactivity (off-season).

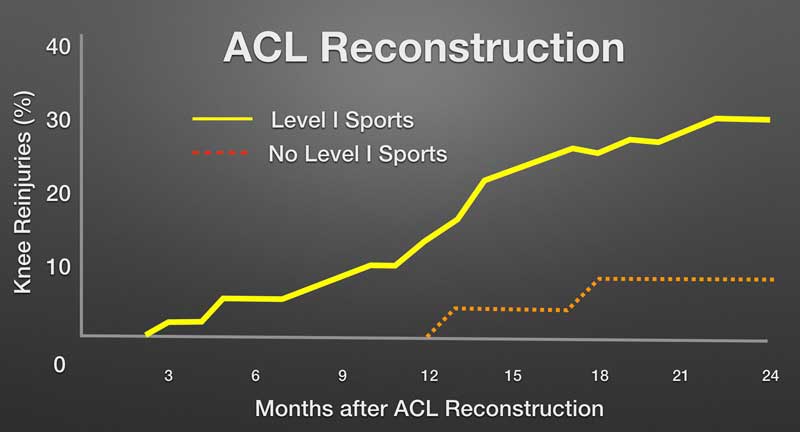

Injury spikes are consistently observed during periods of increased training volume following a break from organized training.20 A recent Norwegian study demonstrated that all athletes who returned to sport less than five months after an ACL reconstruction suffered knee re-injury.1

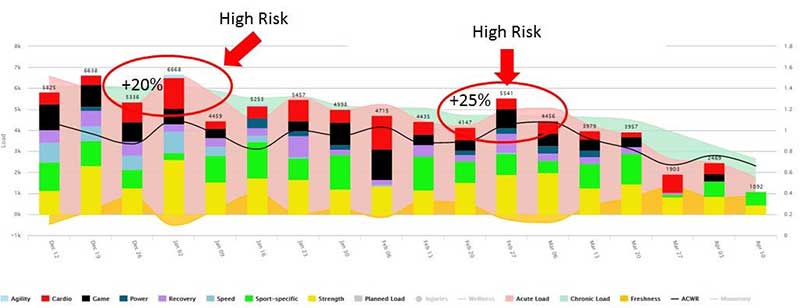

Another study from Gabbett2 demonstrated that when workload increased by at least 15% from one week to the next, the risk of injury jumped by up to 50%. Increasing load too fast is a major risk factor.

Solution

- To reduce the risk of injury and re-injury, base your return to sport decisions on the latest sports medicine research and allow the injured athlete the recommended recovery time–even when external pressures are mounting for a faster return to competition. Once they return, increase workload very progressively (<10% per week) using the athlete’s feedback and perceived wellness scores to guide load progression.3

- One of the best preventive measures for athletes returning from the off-season is to have had them continuing to train and staying fit during the time off.

- Plan your off-season training program so the last week’s load will be about 15-20% lower than the first week of the pre-season. This load will fall in the moderate risk zone, making the return to pre-season training much less risky.

- Keep week-to-week load increases under 15% to contain risk to minimal levels.

- Some athletes are reluctant to train during the off-season, and scheduling a fitness testing session as the first pre-season session can act as a strong motivator.

Weekly Load Is Too High

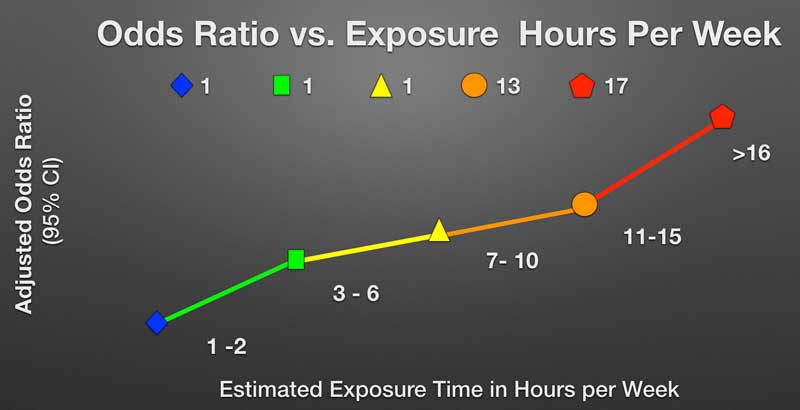

When overall training or competition load exceeds the athlete’s capacity, burnout and overuse injuries are likely to occur. This often affects young athletes who compete in multiple teams and sports or who focus intensively on one sport.

For example, recent research6 indicates that when young athletes train and compete for more hours per week than their age, the risk of overuse injury can increase by up to 70%. For example, a 12-year-old should not train and compete for more than 12 hours per week.

A 12-year-old should not train and compete for more than 12 hours per week. Share on XWhile the ability to sustain high loads and stay healthy is a prerequisite to reaching top performance, it takes time to build tolerance for high loads. It’s a multi-year process and trying to rush the process will likely lead to negative outcomes.

Solution

- Monitor training and competition weekly: volume in hours, rest days, and daily wellness.

- Ensure the weekly schedule includes at least one day of complete rest.

- Alternate hard, easy, rest, and moderate days. Intensive training combined with a high Monotony Index (>2) is an important risk factor for illness and overtraining.7

- Over the course of several months, increase weekly volume very gradually and only when wellness measures reflect a positive adaptation to load. Wellness measures include such things as fatigue that’s not excessive, good sleep quality, low stress, and stable mood.

- For young athletes, use their age to guide the weekly training and competition volume. This is a simple and effective approach to maximize performance while preserving the athlete’s health.

- Proactively reduce training load by 40-50% during exams, back to school, and other stressful periods you are aware of.

- Educate athletes, coaches, and parents about the risks associated with too much training and the need to keep the weekly load at age-appropriate levels. You can do this during meetings by explaining the impact of excessive load on injuries, fatigue, and underperformance using printed material, slide shows, and Internet sites.

Training Loads Are Not Adjusted Daily

If we don’t monitor the athlete’s response to load daily and make program adjustments, even the most carefully crafted training program has a strong chance to produce unexpected outcomes. The reason is simple: Each athlete’s optimal load fluctuates on a daily basis and is affected by multiple factors such as training level, fitness, health, nutrition, sleep, stress, and fatigue.

When load is not adjusted daily, large differences between planned and real training effects will likely occur. This often translates to athletes getting sick before or after a competition, getting injured, and being unable to achieve peak performance when planned.

Solution

As coaches, we often forget that non-sport activities and external stressors3 such as work, friends, school, financial, and family play a large role in determining an athlete’s pre-training fatigue, sleep quality, recovery, motivation, and ultimately performance.

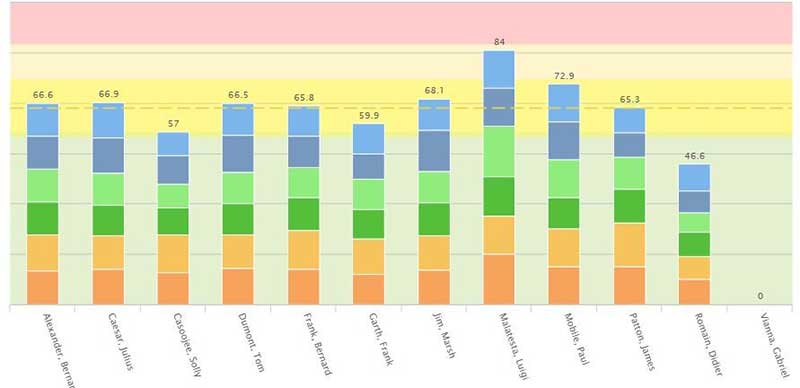

- A simple, reliable, and scientifically validated solution to identify non-sport stressors8, 9, 10 is to ask athletes to complete a short daily wellness questionnaire and use the wellness scores to adjust daily load.3

- To maximize compliance, use a short questionnaire with 5-6 questions regarding symptoms of overreaching (mood changes, poor sleep quality, soreness, excessive fatigue, etc.).

- Once athletes have completed the questionnaire, analyze the answers to detect those who need recovery and rest as well as those who adapt well to the workload.

- When an athlete reports poor wellness measures, reduce the planned daily load. For example, replace a hard session with an easy one or reduce the number of intervals. When symptoms persist more than 2-3 days, reduce load by 40-50% for the next 7-10 days and talk with the athlete to identify potential lifestyle, training, or environmental stressors.

- When the athlete’s wellness scores are good and reflect a positive adaptation to workload, increase next week’s load slightly (4-5%).

Training Is Not Fun

Young athletes have identified lack of fun as the number one reason for quitting their sport.12 As coaches, we often focus on the technical, tactical, and physiological aspects of training and physical preparation. We sometimes forget that enjoyment is a crucial factor of intrinsic motivation, which is a direct predictor of effort and persistence.13

Enjoyment is crucial for intrinsic motivation. Add some fun to your training sessions. Share on XPeak performance requires athletes to be fit, motivated, and ready to compete both physically and mentally. Enjoyment plays a large part the performance equation. When athletes don’t like what they do, they won’t be motivated to train hard and won’t be able to train and compete to the best of their abilities.

Solution

- A simple way to maximize your athletes’ engagement, motivation, and performance is to ask them to self-report their level of enjoyment of training sessions. Tweak your programs and sessions to allow athletes to enjoy their experience.

- Work with the highest professional standards but don’t take yourself too seriously. Smile often, chat with athletes–but don’t fraternize, be open to last minute program changes.

- Add some fun to your sessions. Adding fun doesn’t have to be elaborate. It can simply take the form of warm-up games, a fun challenge, team relays, and athlete-directed cool-downs.

- Be very careful when using super hard workouts, circuits, and army-like workouts. They can be motivating once in a while, but they’re rarely fun for all, they’re mentally hard, and they significantly increase the risk of injury and illness, including rhabdomyolysis.19 These extreme workouts must be used very sparingly and carefully and only with fit athletes who are adequately prepared (see mistake number 1).

- The pressure to train hard and win from coaches and parents can remove all the fun from sport. As coaches, we should try to keep these aspects away from the training environment and keep our sessions focused on improving the athletes’ KPIs to achieve the performance goal and also have fun.

Not Actively Seeking Feedback from Athletes and Sport Coaches

The success of any monitoring program depends on the athletes’ and sport coaches’ collaboration and willingness to share feedback. Without the will to provide honest and regular feedback as well as your openness to adapt programs based on their suggestions, your monitoring program will not work.14

We have lots to learn from athletes and sport coaches. Top athletes often have much more training and direct competition experience than we do. We can have a Ph.D. in sports science, but experienced athletes and coaches have Ph.D.s in performance. They know what works best for them and what doesn’t. Their feedback and suggestions will make your program better and more effective. It should be actively sought.

Feedback from athletes and sport coaches will make your program better and more effective. Share on XWhen athletes share personal feedback, and you don’t act upon it, or if you use the information against them with punishment, mockery, team selection, etc., they will stop sharing it. When sport coaches share feedback, recommendations, and suggestions and you don’t act upon the information, you may end up fired. And that will be the end of your monitoring program.

Solution

- Your monitoring program depends on honesty, trust, mutual respect, and open communication. Meaningful feedback from athletes and coaches is the only information from which you can derive useful insight. To receive meaningful feedback, you should trust them, and they should trust you. If they start cheating or stop cooperating, your monitoring efforts are doomed.

- Athletes must know why you’re collecting feedback and asking all these questions. A possible answer could be: to help them perform better and stay healthy as long as possible. Once trust is established, and they understand they can provide personal feedback and suggestions without fear of negative consequences, they’ll happily share it.

- When they report that they’re tired, didn’t like certain sessions, etc., make sure to tweak your program to include their remarks (after having discussed the planned tweaks with the sport coach). They’ll be grateful to you and even more committed to the team’s success.

Not Measuring the Right Things

In the age of sport technology, wireless sensors, and powerful marketing campaigns by device manufacturers, it’s easier to focus on the wrong metrics. This will lead to wrong load management decisions.

For example, measuring the volume of high speed running by a soccer player (external load) with an accurate GPS tracker will not provide any information on how the athlete tolerated the high speed running (internal load). Low-tech session-RPE is the best tool to monitor the athlete’s response to load.

Similarly, using heart rate to measure the internal load of volleyball players often leads to erroneous load estimations. The reason is simple: heart rate measures underestimate the internal load of short-duration high-intensity, anaerobic activities like volleyball.16 They can’t accurately measure the players’ internal load.

Solution

- Use technology tools for the activities for which they’re desinged: measuring distances, power, speed, and internal load but only for aerobic activities. Using them for things other than their purpose will likely generate useless data and lead to wrong decisions.

Conclusion

- To avoid the common load management errors, monitor daily wellness, quantify internal load using the session-RPE method, collect enjoyment ratings for all sessions, learn from athletes’ and coaches’ feedback, and adjust load daily.

- Administer performance tests that reflect the KPIs of your sport or competitive event.

- Don’t increase load more than 15% per week. If an athlete is not prepared for a load, don’t submit them to it.

- Keep it fun and keep it simple.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

- Simple decision rules can reduce re-injury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study, Br J Sports Med, 50(13): 804-808, 2016.

- Gabbett TJ.: The training—injury prevention paradox: should players be training smarter and harder?, Br J Sports Med, 50(5): 273–280, 2016.

- Soligard T, et al.: How much is too much? (Part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury, Br J Sports Med, 50(17): 1043-1052, 2016.

- McLean SG, Samorezov JE: Fatigue-induced ACL injury risk stems from a degradation in central control. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 41(8): 1661-1672, 2009.

- Stevens ST., et al.: In-game fatigue influences concussions in national hockey league players, Res Sports Med, 16(1): 68-74, 2008.

- Jayanthi N, et al.: Sports specialized risks for reinjury in young athletes: a 2+ year clinical prospective evaluation, Br J Sports Med, 51(4): 334, 2017.

- Foster C.: Monitoring training in athletes with reference to overtraining syndrome, Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 30(7): 1164-1168, 1998.

- Gallo, et al.: Pre-training perceived wellness impacts training output in Australian football players, J Sports Sci., 34(15): 1445-1451, 2015.

- Mann JB, et al: Effect of Physical and Academic Stress on Illness and Injury in Division 1 College Football Players, J Strength Cond Res, 30(1): 20-25, 2016.

- Saw AE, et al.: Monitoring the player training response: subjective self-reported measures trump commonly used objective measures: a systematic review, Br J Sports Med, published online Sept. 30, 2015.

- Di Fiori, et al.: Overuse Injuries and Burnout in Youth Sports: A Position Statement from the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, Clin J Sport Med, 24(1): 3–20, 2014.

- Kelley B, et al.: Hidden demographics of youth sports, ESPN, published online July 11, 2013.

- Fraser-Thomas J., et al.: Examining Adolescent Sport Dropout and Prolonged Engagement from a Developmental Perspective, Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 20(3): 318-333, 2008.

- Saw A, et al.: Monitoring Athletes Through Self-Report: Factors Influencing Implementation, Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 14(1): 137-46, 2015.

- Bosquet L, et al.: Is heart rate a convenient tool to monitor over-reaching? A systematic review of the literature, Br J Sports Med, 42: 709-714, 2008.

- Little T, Williams AG: Measures of exercise intensity during soccer training drills with professional soccer players. J Strength Cond Res, 21(2): 367-371, 2007.

- Jayanthi N, et al.: Sports Specialization in Young Athletes: Evidence-Based Recommendations, Sports Health, 5(3): 251-257, 2012.

- Mc Lean BD, et al.: Neuromuscular, Endocrine, and Perceptual Fatigue Responses During Different Length Between-Match Microcycles in Professional Rugby League Players, International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 5: 367-383, 2010.

- Rawson ES, et al.: Perspectives on Exertional Rhabdomyolysis, Sports Med, 47(1): 33-49, 2017.

- Sole CJ et al.: Injuries in Collegiate Women’s Volleyball: A Four-Year Retrospective Analysis, Sports, 5(26), 2017.

Very informative- enjoyed reading it.

As a strength and conditioning student athlete myself, feeling grateful to have opportunities accessing 5 star infos and guidance like this