I’ve always had a knack, or perhaps a perceived knack, for the “technical” bits of coaching. Seeing technical errors was easy for me. Early on in my career, however, I struggled to get buy-in and engagement with larger groups of athletes, especially with the younger ages. Even if the feedback I gave was gold, the majority of athletes had glazed-over eyes and didn’t seem as excited with the session as I was.

As a performance coach who works with power-speed sports, my goal is to make athletes fast. Not just fast in training: I want them to look noticeably faster when they are actually playing their sport. I was, and still am, heavily influenced by track and field training methods. I’d start my speed sessions with general warm-up circuits followed by sprint drills and ramp up throughout the session to the explosive and fast stuff.

They were money sessions.

What youth or teenage team sport athlete likes to do repetitive drills that they may perceive to be boring or out of context for their sport, asks @CoachGies. Share on XBut let me ask you, what youth or teenage team sport athlete likes to do repetitive drills that they may perceive to be boring or out of context for their sport? A very small percentage. Some kids will really buy in, especially high-performing athletes or kids who have previous track and field experience. In my experience, however, many athletes become bored or lose interest with these types of training sessions.

And what do kids do when they are bored and disengaged? They don’t try, they goof off, they pester other kids…but more importantly, they don’t benefit from the session. As a coach with an introverted personality, I am not, and will not be, a militant-type coach who yells and intimidates kids into doing a session or drill. That’s not my style. I needed to find another way to create the buy-in and engagement while still making athletes incredibly fast and athletic.

What Are We Actually Trying to Develop in Athletes?

Speed.

Faster athletes are generally more effective than slower athletes and better at other skills like jumping, accelerating, and change of direction speed.1 Every sports coach wants fast athletes, and every performance coach wants to develop them.

One thing that perplexed me as a young coach was the paradox between “gym speed” and “game speed.” On one hand, there would be the athletes who looked quick and explosive in training and then looked pathetic on the field. Think of those rugby or football athletes who can absolutely SMASH a tackle bag but look like marshmallows when trying to tackle a live opponent. On the other hand, you have average-looking athletes in the gym who aren’t overly quick or have subpar motor execution, but put them on the field of play, and they shine.

This haunted me as a performance coach. Why didn’t the increased testing numbers they were getting show up on the field of play immediately…or even at all? Why didn’t 1+1=2? I wasn’t satisfied with just dusting off my hands and saying, “Well you got stronger in the gym, faster on the track, better at your agility test…my job’s done. Not my fault if you still suck at your sport!” To find the answers, I had to get 10,000 feet above and look beyond the physical side of our profession.

Expanding My Fishbowl: A More Holistic View of Athlete Performance

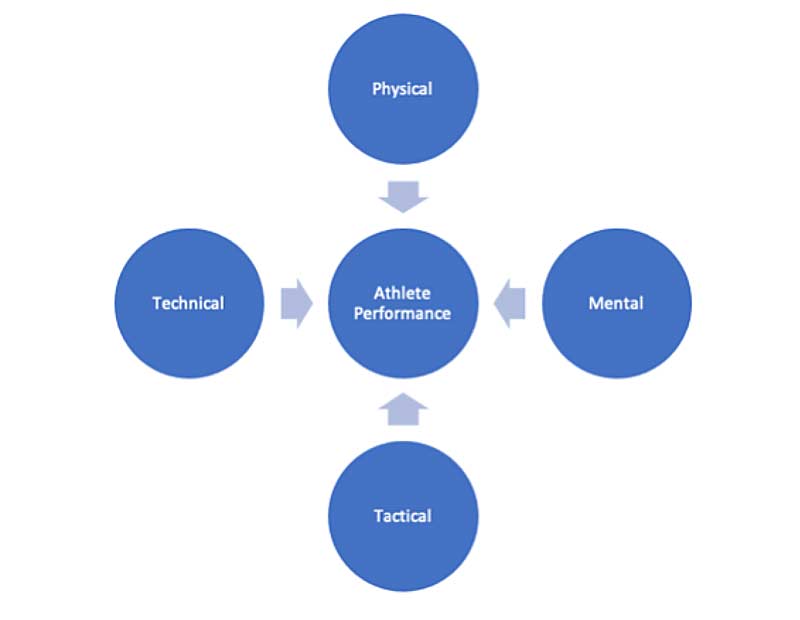

To really understand what goes into athletic performance, we need to look beyond the physical components. This is tough for us S&C coaches, as our job generally centers around physical preparation, and many of us got exposed to the profession through our love of training (or, more accurately, lifting). Many years ago, I was exposed to the idea of a more expansive model of how to impact actual athletic performance, which was the Four-Coactive Model of Player Preparation by Fergus Connolly and Cameron Josse (Figure 1).

This model highlights how successful athletic performance cannot exist without the harmonious interplay between four distinct domains:

- Physical: Motor, neuromuscular, and energy system performance.

- Mental: Emotional intelligence, ability to handle stress, individual’s identity, moral/ethical code.

- Tactical: Effective decision-making (context-specific); focus on completing the task, not on their movement during the task.

- Technical: Body and spatial awareness, vision, adaptability of movement solutions to accomplish tactical goals.

If we just want athletes who top the testing charts, we could likely focus on the physical domain. But if we want to truly develop high-performing athletes in their sport, we need to view development much more holistically.

If we want to truly develop high-performing athletes in their sport, we need to view development much more holistically, says @CoachGies. Share on XNow, this model isn’t meant to suggest there is a perfect division of how important each aspect is to overall performance (e.g., athlete performance is only 25% attributed to the physical abilities of the athlete), but rather, it highlights just how complex athletic development is. Some sports may involve larger portions of a particular category (e.g., archery vs. powerlifting) or even particular positions (e.g., lineman vs. quarterback), but the concept remains the same.

As we can see, the physical capacities of the athlete are only partially responsible for how successful an athlete will be. Their movement patterns are only partially responsible. Their squat 1RM is only…well, you get the idea. The beauty of this model for the S&C coach is it highlights potential gaps in an athlete’s overall development that we can target with our training programs. If the athlete has good physical qualities—but still sucks at their sport—maybe increasing their strength or jumping numbers won’t have the greatest return on investment?

Game Speed – The Golden Goose

Linear speed is obviously a key performance indicator for many sports, yet how many times have we seen fast athletes not excel in sport due to their inability to get open, step around a defender, or explode through a gap? Or another question: How do less quick athletes level the playing field?

If we look at research on the NFL Combine, we can see it lacks predictive ability for actual game performance,2 so giving too much weight to an athlete’s raw physical abilities may provide false positives or lead to overconfidence in a training program’s usefulness in terms of its ability to improve on-field performance.

Is linear speed the Golden Goose (read: something that gives you an advantage) of team sport success, or is there more to it?

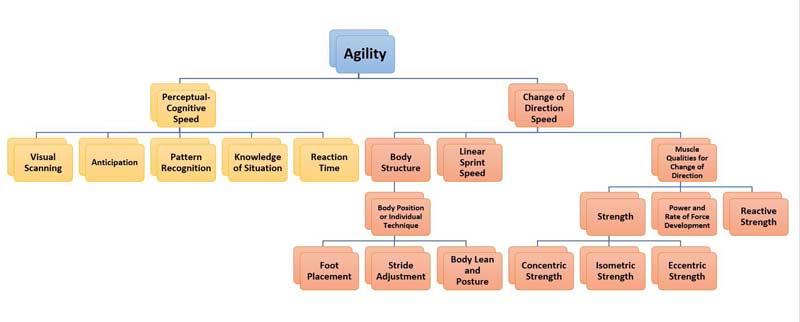

Being fast in response to what’s unfolding in front of you is likely more important. As Sophia Nimphius explains, “Agility is the perception-cognitive ability to react to a stimulus (i.e., defender or bounce of a ball) in addition to the physical ability to change direction in response to this stimulus.”3 Yes, things like strength, linear speed, and change of direction ability contribute to agility performance…but it is the non-physical elements of the previously mentioned Four Coactive Model that really tip the scales. The perceptual-cognitive aspects allow you to use those physical abilities in a more beneficial manner.

If we look at Figure 2, we can see how much goes into a successful agility performance. It is a combination of change of direction speed (which, in and of itself, is made up of linear speed, various physical capacities, and technique) AND the ability to perceive and react to game-relevant inputs. As a young coach, I was too focused on improving the right side of the chart…no wonder my athletes looked great in the gym and average (or worse) on the field.

As Ian Jeffreys describes in his aptly named book, Gamespeed, “There will always be a context-specificity to the task, with the athlete moving with control and precision with the ultimate aim of successfully carrying out the task at hand. Importantly, this is not purely reactive, as the athlete will be constantly adjusting and manipulating his movements in relation to the way the environment is evolving around him”4 (emphasis added).

Game speed, and the ability to perceive relevant stimuli and react accordingly, is the Golden Goose of sport performance, says @CoachGies. Share on XThis was another eye-opening realization for me as a physical preparation coach. In my training sessions that focused on improving game speed or agility, how often did I create environments or drills that forced my athletes to take in some sort of external stimulus, causing them to adjust or manipulate their speed and movements in response? Very little to not at all. And I’m not talking about basic reactive cues like the coach yelling “Go!”, a clap of the hands, or pointing where to go; I’m talking about actual game-relevant stimuli.

[vimeo 508640002 w=800]

Video 1. “Spider’s Web” game. Lay out a large amount of cones in a random pattern, with 2-3m between cones. One player is the spider, and the others are flies.The goal is for the spider to tag all of the flies (see Appendix below for full game rules).

My training sessions were only ever about max intent, without a thought of the outside world: sprint 30 meters, do this pro-agility drill, jump for max distance. These are crucial training elements for creating physically dominant athletes…but they are not the only things determining greatness. Game speed, and the ability to perceive relevant stimuli and react accordingly, is the Golden Goose of sport performance.

Sharpening the Saw: Is a Games-Based Approach to Athletic Development the Missing Link?

Hopefully, I have convinced you that developing a skilled athlete is more than just about improving physical attributes (e.g., the Four Coactive Model). Improving the technical, tactical, and mental abilities of an athlete will result in players who can perceive and move with very high quality, in a variety of complex situations. The question now is: How the heck can I, an S&C coach, improve all of these areas in training? Isn’t all that fluffy stuff the job of the sports coach?

Enter the “Games-Based Approach”

Work done by Kinnerk et al.5 highlights the differences between traditional styles of coaching and games-based approaches (GBAs). In traditional models of coaching, athletes need to master technique before gameplay. There is an emphasis on skill work in overly simplistic and unpressurized situations that do not mimic the demands seen in a real game (sounds like some S&C programs). Ultimately, this creates a separation between the technique and the tactical knowledge, causing a disconnect between training and the game where players are not able to respond to game situations. Sounds a lot like my own dilemma that I spoke about at the beginning of this article!

Incorporating games into your athletic development programs will allow athletes to integrate all aspects of athletic performance in a more sport-like scenario. What do these types of games generally look like? Athletes running full speed, changing direction at high speeds, jumping, scanning, detecting, communication, tactics, strategizing, various skills, high metabolic demand, engagement, enjoyment…all at the same time! By altering classic schoolyard games or creating your own game, you will be able to create environments that foster learning and experimentation, physical and tactical development, and—more importantly—buy-in and fun. GBAs are a useful way for S&C coaches to help improve the transfer of skills to performance, rather than being the silly time wasters that I fear many dogmatic S&Cs may perceive them to be.

Incorporating games into your athletic development programs will allow athletes to integrate all aspects of athletic performance in a more sport-like scenario, says @CoachGies. Share on XNow before a mob of sprint coaches comes after me, this isn’t to say more structured training sessions breaking down and emphasizing portions of a specific skill or movement pattern aren’t warranted or necessary, especially when we are discussing beginners or athletes learning new skills. Technical development and movement proficiency are a fundamental piece of the S&C coach’s job description. But GBAs are an effective way of integrating the physical, technical, mental, and tactical elements of the Four Coactive Model.

[vimeo 508641622 w=800]

Video 2. “Cone Scramble” game. The player with the ball cannot step on a cone if another player is touching it; as they run around looking for free cones, the other players must work to cover up the cones (see Appendix below for full game rules).

I have found in my own coaching that GBAs create greater engagement, buy-in, and effort among my athletes, with no decrement to physical development, movement skill, or performance. In fact, I have found an increase in how my athletes move and problem-solve in a wide variety of situations. They become faster, fitter, and more agile. Most importantly, they look better on the field of play.

Now that you are completely onboard with the idea of GBAs being beneficial for performance coaches, let’s take a look at one of my favorite games…Bank Ball.

Bank Ball

This game is best played with a rugby ball, but a volleyball or similar will do. Split your group into two even teams (5-10 athletes per team works best). Create a grid of your choosing but having enough space for some open running or long passes is ideal. I generally set up a 20-30m x 20-30m grid on a grass field, but a basketball court works well, and something smaller could also work.

Decide on a number between 5 and 25 (depending on the skill level of the players, but I usually start with 5), and the goal is for one team to complete that number of passes consecutively. Once that number of passes has been achieved, the player who caught the last pass needs to touch the ball to the ground and yell “BANK.” That team then banks those accumulated passes and now has one point. We generally play first to 10 points wins.

I introduce this game slowly, where the ball can only be turned over through one of three ways:

- The team with the ball screws up a pass, causing the ball to hit the ground.

- The other team knocks it out of the air.

- The ball/player goes out of bounds.

I also don’t allow players with the ball to move—only pivot—so the other players need to work to get into space. I’m a stickler for communication, so each team needs to count their passes aloud as a group (i.e., all yelling “1…2…”) or else I make them restart their passes from zero again. I find athletes are more engaged when they are calling out passes. Similarly, if a player touches the ball down to the ground and doesn’t yell “bank,” they don’t get a point. A player only needs to feel the shame of losing their team a point once to never do that again…

Once the group gets a handle on the basics of the game, we start to ramp it up with variations:

- Allowing players to run with the ball, and if they get tagged, it’s an automatic turnover.

- Increasing the number of passes needed before you can bank the ball.

- If a player kicks the ball and a teammate catches it, they earn an automatic point.

And the list goes on…

Once you get to this point, it is an extremely fast-paced, high-energy, and engaging game. Kids will play this for hours, running harder than any endurance protocol, practicing a variety of skills (i.e., kick, throw, catch), and getting countless linear and multidirectional reps, all while perceiving and reacting to other players and a ball…what else do you want? Achieving all of that with traditional training means in the same time frame is nearly impossible. You can then add countless additions or changes to keep it interesting or focus on a skill unique for the group you are working with. I often make new rules/changes on the fly to keep things interesting.

Give it a try with your athletes: They’ll love it. The game is especially fun when you have a mix of athletes from different sports.

Intuitive Athletic Development Through Games

When you think about it, why do kids play sports? Because sports are fun! They love to compete, beat their friends, get bragging rights…they love to WIN. They don’t care about tissue tolerance, shin angles, maximal aerobic speed, and everything else we (S&C coaches) argue about on Twitter.

Games create the optimal environment to get kids developing sport-specific athletic qualities, as well as improve their tactical, technical, and mental abilities, without even knowing it. Share on XI urge you to reflect on the majority of your training sessions and see how often you include environments that touch on all aspects of the Four Coactive Model for Athletic Performance in a fun and stimulating way. Games create the optimal environment to get kids developing sport-specific athletic qualities, as well as improve their tactical, technical, and mental abilities, without even knowing it.

Appendix: Game Rules & Setup

1. “Spider’s Web” Game

• Lay out a large amount of cones in random order (2-3m between cones)

• One player is the spider, the other players are flies

• The goal is for the spider to tag all other players

• Players can only run in straight lines from cone to cone, and only to cones that are in close proximity (can’t run to a cone across the playing area).

• Players must touch a cone with one foot before they can run to another cone

• If a player gets tagged, they must stand on the cone they were at and now that cone is “dead.” Players cannot use that cone, which alters the available playing area and changes the possible moves a player can make

-

o The more tagged players, the more challenging it becomes

• Spiders are allowed to use the dead cones

• Two players cannot be on a cone at the same time

• You can only stop on a cone (not in between cones), and once you commit to running to a cone you cannot come back the way you came until you touch the cone (meaning, if the tagger is going to the same cone, the fly still has to reach that cone).

Benefits of Game

-

o Planning running routes (tactical awareness) and rapidly altering those plans based on other players’ movements

o Evasion

o Scanning and awareness of surroundings

o Change of direction and short accelerations

o Anaerobic conditioning

2. “Cone Scramble” Game

• This works best with a minimum of 6 players

• Randomly scatter cones 1-3m apart (have one more cone laid down than the total number of people involved)

• Place 2 pylons down, one 10m away from the playing area, and the second one 15m away from the playing area (more on this shortly)

• Have the players circled up in the middle of the cones passing the ball quickly amongst themselves

• When the coach shouts GO, the player holding the ball runs around the 15m cone cone and the rest of the players run around the 10m cone

• The goal for the player with the ball is to step on 2 separate cones; the goal for the other players is to work as a team and prevent the player from stepping on 2 cones for as long as possible

• The player with the ball cannot step on a cone if another player is touching it, as they run around looking for free cones, the other players must work to cover up the cones

• Keeping a player from touching 2 cones for more than 30 seconds is incredibly challenging

Benefits of Game

-

o Communication between players to ensure cones are being covered (cannot cherry pick on a cone or else the player with the ball will win very quickly)

o Scanning and awareness of surroundings

o Change of direction and short accelerations

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Loturco, I., Pereira, L.A., Freitas, T.T., et al. “Maximum acceleration performance of professional soccer players in linear sprints: Is there a direct connection with change-of-direction ability?” PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0216806.

2. Cook, J., Snarr, R., and Ryan, G. “The Relationship Between the NFL Scouting Combine and Game Performance over a 5 Year Period.” Conference: Southeast American College of Sports Medicine. February 2019.

3. Nimphius, S. “Increasing Agility.” In: Joyce D, Lewindon D, editors. High-Performance Training for Sports. Champaign (IL): Human Kinetics; 2014. p. 185-187.

4. Jeffreys, I. Gamespeed. 2nd ed. Monterey (CA): Coaches Choice; 2017.

5. Kinnerk, P., Harvey, S., MacDonncha, C., and Lyons, M. “A review of the game-based approaches to coaching literature in competitive team sport settings.” Quest. 2018;70(4):401-418.