[mashshare]

NOTE: The following article is a rendition excerpt from Level I in a book series written by Dr. Fergus Connolly and Cameron Josse entitled The Process: The Methodology, Philosophy & Winning Principles of Coaching Winning Teams, which is now available from Ultimate Athlete Concepts here.

Contrary to common belief, the physical make-up of a player (when considered in isolation) does not determine player success on the field. The truth is that physical prowess is only one factor in terms of what goes into being a successful player. We cannot isolate the physical ability of a player without considering how it interacts with psychological well-being, technical skill, and tactical awareness.

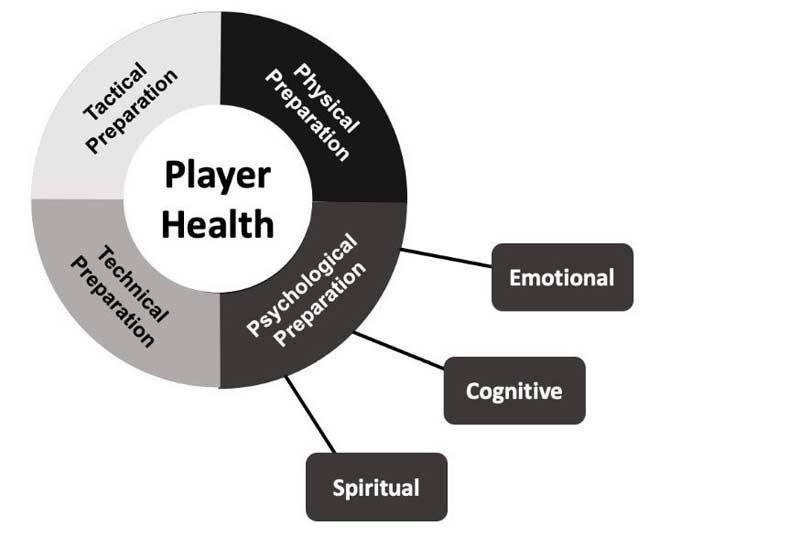

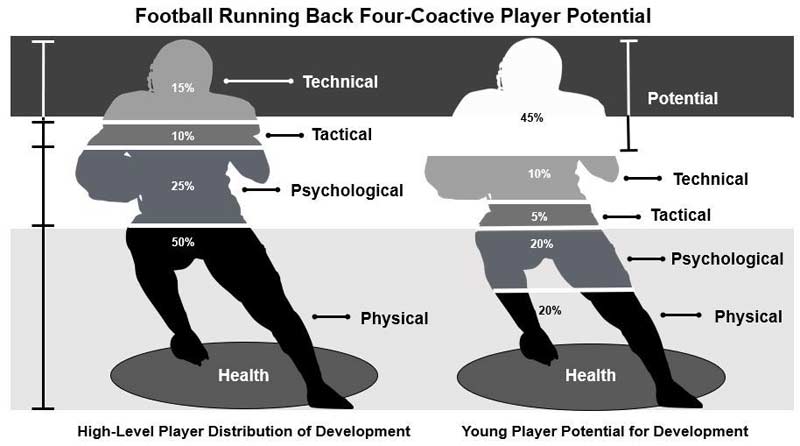

Based on these aspects, a Four-Coactive Model is a more complete assessment of player potential. In it, there are four elements of player preparation, all of which are intertwined and interdependent:

- Tactical Preparation

- Technical Preparation

- Psychological Preparation

- Physical Preparation

All four elements are present to varying degrees in every moment of a team sport game. They are also present during all forms of practice and preparation. They are called “coactives” because they both complement and rely upon each other. These four coactives must come together in a synchronized manner for the player to execute effectively. They cannot exist without each other. They are complementary, codependent, and co-reliant.

In addition, it is a mistake to analyze these four coactives without considering the most vital aspect of player preparation: health. Player health is an essential umbrella that affects all four coactives. Without health, none of the other coactives matter in the long run.

The Tactical Coactive

When it comes to game-day performance, each player’s tactical acumen is the front-runner of the four coactives. If players don’t understand what to do when they’re on the field, then they simply can’t help a team win. When assessing performance, coaches often attribute failures of execution to physical shortcomings. But often, high-level players have more than enough physical competence to do what is needed. After all, they are recruited for this purpose.

Instead, what we typically find is that unsuccessful players lack the requisite tactical know-how. This also means that just because a player is a physical specimen, that player is not excused from understanding how to position on the field or from adhering to the play calls.

Often, high-level players have more than enough physical competence to do what is needed, but we typically find that unsuccessful players lack the requisite tactical know-how. Share on XFostering Effective Decision-Making

One element of tactical preparation that’s often overlooked is improving player decision-making on the field. The exercises, drills, and games designed for training and practice should focus on the desired tactical outcome at the individual, unit, and team level. This will help players perform by focusing on successfully completing the task rather than being overly self-conscious of their movement.

Learning opportunities are dictated by what the current scenario looks like and what players can draw on from their past experiences. This is exactly how they will operate in the game. It’s essential that tactical team periods of practice and scrimmages occur at, or above, game tempo so that the players learn to execute under pressure on game day.

The tactical preparation is based on the next game on the calendar. While maintaining team principles, coaches might recognize a dominant quality in the opposing team that needs to be mitigated, such as the threat of a game-breaking player. Coaches might also find a limiting factor in the opposing team that can be exploited, so they can design tactics to take advantage of this.

Tactical Player Load

Developing tactical awareness is more inclusive than just running through plays on the field. This form of training is highly cognitive in nature. Film study, whiteboard work, walk-throughs, and situational awareness are all forms of tactical preparation.

Just like the other coactives, the tactical coactive creates a stress load on players, but this stress affects their brains more than on their bodies. While film study might not be physically stressing for players, the duration must be considered as part of the cumulative stress load for the day.

Coaches simply cannot put players through high-intensity, high-volume sessions across all four coactives, day after day. If they do, they’ll compromise learning outcomes, and the players will be worn down going into the next game. Therefore, the tactical sessions must be balanced with all other stressors during the weekly cycle of training.

The Technical Coactive

A player’s technical skill is an oft-misunderstood form of preparation. In the same way that scouts and commentators over-emphasize a player’s physical make-up, they also over-emphasize a player’s movement, attempting to fit it into a perfect, one-size-fits-all technical model.

However, recent theories on motor control like dynamical systems theory and ecological dynamics suggest the futility of this approach, namely that it is impossible for a player to move exactly the same way twice.1 Even so, it wouldn’t be warranted because the opponents, situations, environments, and other contextual elements of the game are constantly changing.

Therefore, the goal is to build players who move in dynamic, adaptable, and resilient ways to accomplish tactical goals.

Spatial Awareness

The first step in coaching technical skill is to teach players to understand their position and how it relates to those around them. In this way, players will comprehend how to manipulate the space available to them. This is spatial awareness, and it depends on the ability to process what is happening on the field and how the environment will change.

When a player is described as having great “vision,” it is really the perception and ability to process visual information which ultimately dictates the type of physical action chosen. Contrary to popular belief, vision, perception, and game-specific spatial awareness can be developed and trained by engaging in learning tasks that represent aspects of the game.

Contrary to popular belief, vision, perception, and game-specific spatial awareness can be developed and trained by engaging in learning tasks that represent aspects of the game. Share on XWhen players are prepared using representative learning in practice, they will be able to focus more during the unexpected events that occur in the game and feel less overwhelmed. Players will be less self-conscious of their movements and will be paying more attention to what is happening around them, acting through instinct.

The Importance of Context

Context is king. To make preparation more optimal, coaches must constantly keep the context of the game in mind. One should never look at the execution of a skill without considering the context. Just because a player has great “footwork” when working out alone on an agility ladder does not mean anything in terms of functioning effectively within the context of the game.

Transfer to game performance requires perceptual triggers against which to observe and act. These must also be considered in context. For example, adding non-specific perceptual triggers like a coach pointing in a certain direction can help build general reactive ability, but will still lie far outside the game context. It’s not enough to have players reacting to something; the experience must be game-like in order to improve sports performance.

Manipulating Complexity and Constraints

Contextualized activities can be layered in terms of complexity. By adding more players to a practice drill or game, the players must not only account for their opponents, but also their relationship to teammates, making the overall complexity higher than one-on-one situations. Progressing to full team games will produce an environment that is very similar to the game itself. These layers indicate rising complexity where perception of the environment will take on an increasing role.

Even when players look like they’re exhibiting consistent form in skill execution during a game, in reality they are making slightly different movements each time. The best players are those who can operate along a movement bandwidth in which a similar skill can be performed against a variety of constraints and environments. This means that the outputs are consistent in terms of results, like a player beating the man across from him repeatedly, but the manifestation of the result happens in different ways.

Great players are capable of consistently completing tasks by adapting movement solutions to fit the problems they face—all without losing efficiency of movement or effectiveness of solutions. Technical mastery has less to do with how a player moves in a “closed” environment—in the absence of opponents—and more to do with how that player is able to solve varying sport problems with efficient and effective movement solutions.

The bottom line is that we cannot learn (or teach) a skill in isolation and expect it to fully translate to a game setting. Share on XField position, proximity to the end zone, opponents, teammates, ball speed, formation, and time on the game clock are just a few of the many constraints that require players to change how they perform any skill. Additionally, environmental factors—bad weather, crowd noise, and the condition of the playing surface—also shape skill execution. This is why, in a game setting, a skill is never performed the same way twice.

The bottom line is that we cannot learn a skill in isolation and expect it to fully translate to a game setting.

The Psychological Coactive

When profiling or assessing a player from a psychological perspective, there are three micro coactives: spirituality, emotion, and cognition. As with all coactives, these are interlinked and interdependent, but each is a key factor in the performance of the player.

Spirituality

The term spirituality isn’t exclusively about religious belief, although this can be an important part of a player’s spiritual makeup. Spirituality involves an individual’s identity, purpose in life and society, perceived role in society, community, team or tribe, and commitment to things considered bigger than self.

Spirituality encompasses how players see themselves in relation to others. From time to time, players who struggle with relationship issues also struggle to relate to others in the locker room or have difficulties interacting with their coaches. The boundaries between personal and professional relationships are permeable and can’t simply be dismissed as two distinct entities.

One’s moral and ethical code underpins the spiritual coactive. Many young players have yet to find a goal for themselves or understand their place in life. This confusion often affects their ability to identify clear spiritual guidelines early on. The sooner they find this comfort, the easier it is for them to find peace in the perspectives and beliefs they hold.

Players with a strong spiritual center tend to better understand group dynamics and feel more confident about their role in the organization and in society. Someone who lacks this foundation often struggles in this regard. This doesn’t have to be a matter of religious faith; a player may simply be out of sync with the spirit of the team and feel like an outsider who is not involved in the group dynamic.

For players to contribute and feel like part of a team, they must clearly identify a personal reason for why they come in every day and give their all. This is closely related to the player’s needs and identity. There must be a connection on a spiritual level—a sense of belonging or a tangible power of togetherness.

It’s essential that players have the sense that they are invested in the team and that their contributions are valued by the organization. This encourages a sense of responsibility and commitment:

- Meaning: Why am I doing this? Why are we doing this?

- Connection: What do I have to offer? What’s expected of me?

- Control: How can I positively influence my performance and that of the team?

Emotion

Managing emotions on and off the field is an essential prerequisite for high performance and is arguably one of the most impactful components of psychological strength and ability. A player’s decision-making process is partly reliant on past experiences and surrounding observations in the moment, but it’s also closely tied to emotional intelligence and control.

A player’s past and culture can affect emotional responses as well. Emotions are the fastest mechanisms in the body, so they have a great effect on players’ actions and overall performance. How coaches and players communicate verbally and nonverbally sets the emotional context for each interaction.

Recognizing the importance of the emotional preparation of players leads to better decision-makers under stress. Share on XThere’s more than a hint of hypocrisy when coaches display emotional outbursts and then scold players for drawing a penalty flag for acting the same way on the field. The way a workplace carries itself always starts with how those at the top carry themselves. Couple this with the sad reality of coaches who berate and shout at players in practice but then expect the player to remain calm and not react during periods of high stress during games. Coaches like Bill Belichick that have sustained success at a high level typically project a sense of calm and emotional control during the most stressful moments of games. Recognizing the importance of the emotional preparation of players leads to better decision-makers under stress.

Cognition

Cognition is the player’s ability to focus, maintain attention, and mentally process what’s going on during practice and games. Cognition encompasses information-processing, logical decision-making, studying the playbook, on-field awareness, and critical thinking.

It’s perfectly fine for coaches to expect a high-tempo, high-energy setting in practice, but they must also expect full cognitive commitment and concentration from players. Also, coaches can’t lose sight of the cumulative cognitive load that players are experiencing throughout the week; such awareness ensures players can stay mentally fresh come game day.

The ability to focus and learn is profoundly impacted by stress and/or disruption to basic health. Being capable of engaging fully on the practice field, in the film room, or during supplemental learning scenarios, and then transferring these experiences to long-term memory, is inextricably linked to a player’s overall well-being.

Conducting a basic psychological profile or having honest conversations with players and being mindful of areas like emotion, cognitive learning, and self-esteem allows coaches to clarify the areas of greatest need for psychological improvement:

- Does the player handle stress well?

- Is the player emotionally intelligent?

- Are there external issues affecting the player’s mental and emotional state?

- Does the player process and learn information properly and fast enough?

- Does the player feel wanted and part of the team?

- Does the player feel appreciated?

The Physical Coactive

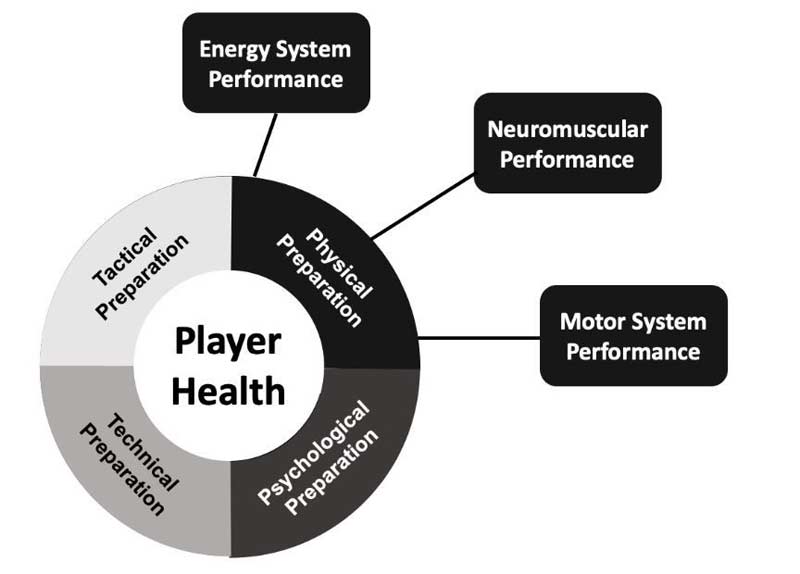

The physical coactive is arguably the simplest to understand because here we are really referring to a player’s fitness. Any form of fitness development or fitness testing will fall under the physical coactive. In our approach, we break down the physical coactive into three primary areas:

- Energy System Performance– The functionality of the aerobic and anaerobic systems (i.e., alactic power, anaerobic capacity, aerobic capacity)

- Neuromuscular Performance– Regimes of muscular work (i.e., concentric, isometric, eccentric, elastic)

- Motor System Performance– The observable outputs associated with performance in sport (i.e., speed, power, strength endurance, speed endurance)

The physical coactive also includes analysis of body composition, mobility, and biomechanics. Again, everything measured in the physical coactive should be understood in context, so asking questions related to areas like strength or speed should always be investigated by working backwards from the game.

Are Our Players Strong Enough?

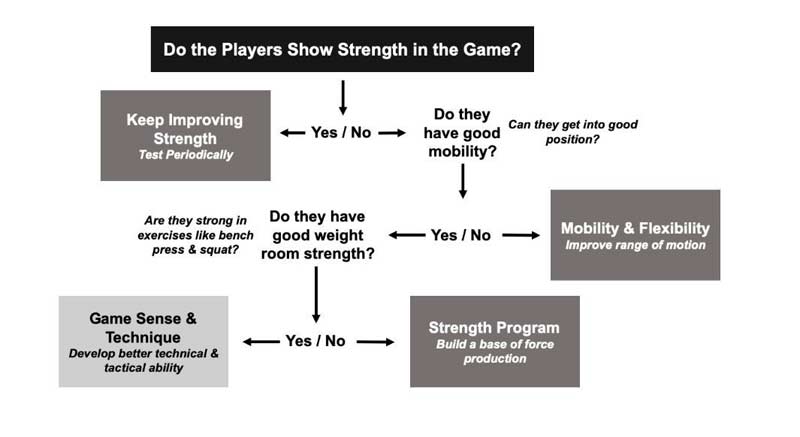

By combining knowledge of biomechanics with a thorough understanding of the sport game, coaches can assess a player’s physical prowess as it relates to game performance. From this vantage point, strength really refers to how well the players can apply force and achieve a specific outcome when faced with various movement constraints.2

This means that strength is not just about how much weight a player can squat or bench press. For strength to be analyzed in terms of its usefulness for sports performance, coaches and scouts must consider the task requirements of each player’s position and the constraints they will face when playing the game.

Perhaps it’s not really a strength issue. Maybe the player does not understand what to do from a tactical perspective or is operating with poor technical execution. Or the player may not possess enough mobility and flexibility to achieve the required technical positions to play strong.

So, while coaches want to see players continue to improve in the weight room from a force-production standpoint, they can keep everything in context by observing how players are operating in the game before deciding that strength is a true limitation.

Are Our Players Fast Enough?

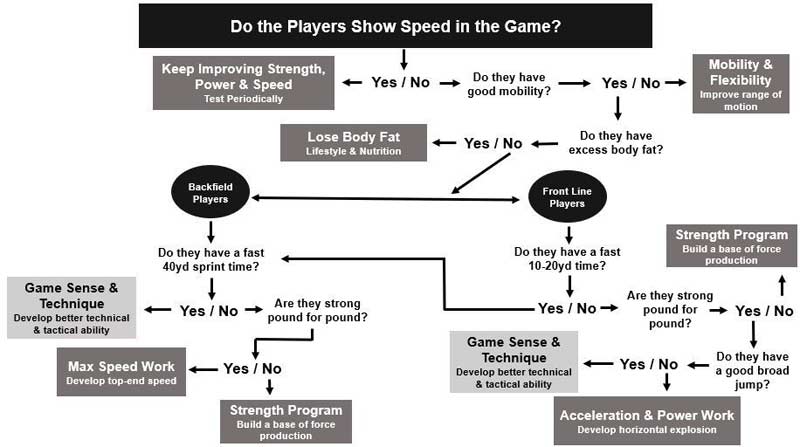

Speed is an interesting paradox as it relates to team sports. Most coaches would agree that they desperately want to recruit speed, even going so far as to question young players on their involvement in track and field. In fact, many players are overlooked simply because they don’t participate in track and field. We live in a time where numbers sometimes seem to be more important than what coaches can see with their own eyes.

In truth, coaches don’t need a 40-yard or 100-meter sprint time to tell them if a player can play fast. All that’s needed is some film to watch how the player plays the game. To be fair, there is no question that a player who can run a fast sprint time will have the potential to play fast. Still, the fact remains: A player’s sprint time will tell coaches almost nothing about how the player plays the game. In contrast, game film will show scouts exactly how the player operates in a game environment. Coaches can ask themselves: Are we recruiting players to run a race, or are we recruiting players to play the game?

Coaches don’t need a 40-yard or 100-meter sprint time to tell them if a player can play fast. All that’s needed is some film to watch how the player plays the game. Share on XSome young players will show some nice flash on film but play in a league that isn’t very competitive, making it tougher to distinguish how these players will function at higher levels of competition. For this purpose, camps are valuable, as coaches can invite players to participate in game-related exercises with other highly touted prospects and see how they perform.

Measuring a 40-yard-dash can help, but its value is as an objective analysis in combination with subjective indicators from watching a player play the game. Some prospects may have never run a 40-yard-dash and may not test well. These same prospects may show great awareness and skill when it comes to competitive game scenarios.

The reality is that game-related speed is far more complex than what is devised from a 40-yard-dash test. Great players understand when to slow things down and when to burst into another gear, all of which is dictated by what they are perceiving in the game environment. While having access to a lot of speed will always be an asset, being able to use that speed in an effective manner when playing the game is the better indicator of success.

Determining Limiting Factors

To the extent possible, coaches must find the limiting factors holding a player back from improving game performance. A mistake often made is assuming that if players can lift 20 more pounds or withstand another four repetitions of 110-yard sprints, they will magically improve on game day. The problem with this approach is that it’s essentially just guess work, often leading to overtraining and underperformance.

Coaches can use the Four-Coactive Model to identify the true limiting factors of player performance in the context of the game. Share on XA far better approach is to use the Four-Coactive Model to identify the true limiting factors of player performance in the context of the game. This way, coaches can clearly see if players need to improve certain physical qualities and they can devise a plan to get there.

It’s also necessary to understand that physical development is not limited to the strength and conditioning sessions. Practice is a form of physical training, so coaches can address limiting factors related to physical shortcomings in practice activities as well.

In fact, by understanding the Four-Coactive Model, the strength staff and sport staff can work together in a coherent way to determine which physical qualities will be addressed in practice and which will be addressed in the strength and conditioning sessions. This is a perfect example of letting the game guide the preparation process throughout the organization.

Health: The Most Important Factor for Sustainable Success

Hands down, player health is the most important factor for achieving maximal and sustained performance. Coaches are not interested in winning one game or going through one successful season…they’re interested in dominating and winning multiple championships. For that, the health of their players is essential.

One of the main goals of the Four-Coactive Model is to enable players to continue making small improvements every day and, ultimately, for these advances to result in more wins. For this to come to fruition, coaches must maintain the overall health of their players as best as possible, especially with busy training schedules.

Hands down, player health is the most important factor for achieving maximal and sustained performance. Share on XPhysical health is a key factor in its own right—players need to be physically fit to play their best. But, it’s also a precursor to achieving balance in the body’s chemistry, which has a positive impact on player mental states as well.

A player who leads an unbalanced, unhealthy lifestyle might be able to cheat biology for a time. But after a while, the cracks will widen into canyons and the player will fall through. Talk to most professional players who have ended their careers earlier than expected and they will say, “I wish I had taken better care of my body.”

While it is the responsibility of the players to take care of themselves, the coaching staff, medical team, strength and conditioning staff, sports science staff, and other members of an organization also have a moral and ethical duty to look after players.

Health is more than just eating right, getting enough sleep, and avoiding excessive drinking or drug use. Trying to attain mental toughness by beating players down physically, day in and day out, seeing if they can overcome it, poses a very high risk to their health. Similarly, when berating players verbally and trying to break them down psychologically through insult and mental manipulation, the damage might not show at first, but the health of that player is likely being sacrificed from the inside-out.

For a more detailed description of the Four-Coactive Model and how it can be used in designing team sport preparation strategies, be sure to pick up Level I of our book series, The Process: The Methodology, Philosophy & Winning Principles of Coaching Winning Teams, available here.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

1. Bunker LK (1999). Progress in Motor Control: Bernstein’s Traditions in Movement Studies. J Athl Train. Jul-Sep; 34(3): 296–297.

2. Jeffreys, I., & Moody, J. (Eds.). (2016). Strength and conditioning for sports performance. Routledge.

Dr. Fergus Connolly is one of the world’s leading experts in team sports and human performance. He is the only coach to have worked full-time in every major league around the world. Dr. Connolly helps teams win at the highest level with the integrated application of best practices in all areas of performance. His highly acclaimed book, Game Changer (with Phil White), is the first blueprint for coaches to present a holistic philosophy for winning in all team sports.

Dr. Fergus Connolly is one of the world’s leading experts in team sports and human performance. He is the only coach to have worked full-time in every major league around the world. Dr. Connolly helps teams win at the highest level with the integrated application of best practices in all areas of performance. His highly acclaimed book, Game Changer (with Phil White), is the first blueprint for coaches to present a holistic philosophy for winning in all team sports.

Dr. Connolly has served as director of elite performance for the San Francisco 49ers, sports science director with the Welsh Rugby Union, and performance director and director of football operations for University of Michigan Football. He has mentored and advised coaches, support staff, and players in the NBA, MLB, NHL, Australian Rules Football, and international cricket. Dr. Connolly has also trained world boxing champions, and he advises elite military units and companies across the globe.

He is a keynote speaker and consultant to high-performing organizations around the world.

Learn more at fergusconnolly.com.