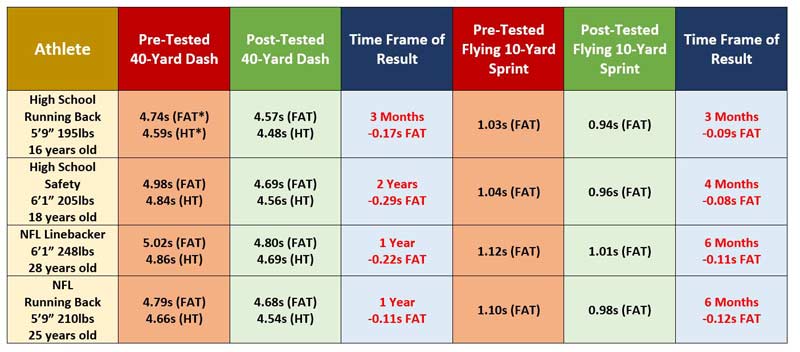

The purpose and goal of this article is to convey my ideas (and mine alone) of improving speed in American football players through increased exposure to the skill of linear sprinting during the off-season. These are some of the principles that I have applied with my players ranging from middle school up through the NFL, and I’ve seen nice improvements. Some of the results that I have achieved using this approach with particular clients are listed in the table below:

Why Train Sprinting for Football?

The need to train sprinting for football might seem pretty obvious. Many reading this article will quickly say, “Uh…football players obviously need speed. Speed kills. We recruit speed. We crave speed in our program. Our program is nothing without SPEED.”

I work with a fair number of high school football players going through the recruiting process who can’t stop talking about how seemingly obsessed college recruiters are about getting them to run a 40-yard dash or quickly asking if they run track and, if so, what their 100-meter time is.

Football recruiting based only on speed needs to change. The game is more than just physical output. Share on XI have seen kids get completely ignored by colleges after running a 40-yard time at their camp that wasn’t up to the coaches’ expectations. Sprint times are becoming the ultimatum for some kids for scholarship consideration. It almost doesn’t matter if you are a better football player than the other guy at your position—if he runs faster than you, he’s likely getting the recruiting look while you continue contemplating how you can play at the college level.

The Four-Coactive Model

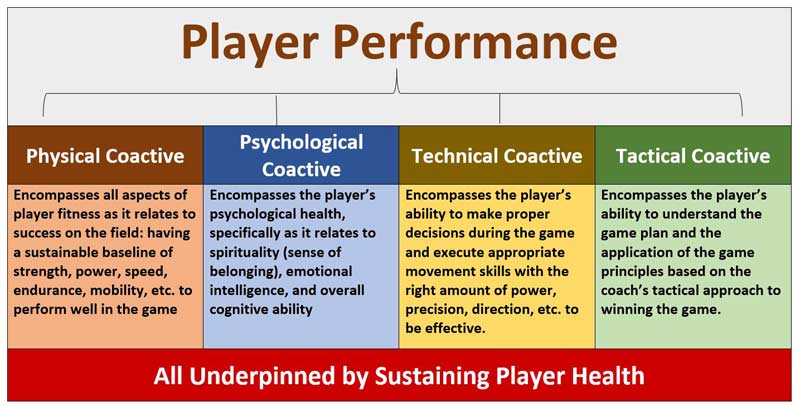

Recruiting based solely on speed needs to change. Anyone that truly understands the game of football and everything that goes into it will support this notion. The game is about far more than just physical outputs. My favorite illustration of this point comes from the Four Coactive Model presented by Dr. Fergus Connolly in his brilliant book Game Changer. I have rudimentarily summarized this model in Table 23:

Based on this model, putting a major focus on a player’s physical traits only tells us about 25% of the whole story in terms of what a player’s true potential as a football player might look like. Compensations certainly exist where a player might make up for a lack of technical skill by having tremendous speed, but any time we see major deficits in any of the four coactives, it should raise a red flag of performance potential left on the table.

That being said, those of us who work with high school or college football players trying to make it to the next level still have to accept the reality of what coaches are currently looking for. And that, unfortunately, means that we need to create the greatest 40-yard-dash-running players possible. However, we should be mindful of how an improvement in speed can have a global effect on each of the four coactives.

The Butterfly Effect of Speed Improvement

I have a common response when I get a call from a client who ran a good 40-yard time in front of scouts or recruiters, and it goes something like: “Great… Now you can focus on playing football.”

While I like to joke about the obsession with 40-yard-dash times, there is no question that speed plays a role in a player’s ability to play at a high level. If technical and tactical ability are equal, a slower player will have to work harder to get to the same area of the field than a player who is faster. When it comes down to what you need to do to make the play, rather than what you can do, then the faster player will always have a physical advantage over the slower player. Plus, when it comes down to the bare-bones, off-to-the-races type of big plays on the football field, speed really helps.

I believe that an improvement in speed is an example of how making gains in one coactive can have a butterfly effect on the others. For one, when athletes feel themselves getting faster and have sprint-testing data to prove it, they get a burst of psychological positivity. I have yet to meet an athlete that isn’t completely hyped about getting faster or feeling fast. I believe there’s no doubt that this affects overall confidence, which can then carry over into practice or game situations when the season rolls around.

An improvement in speed shows how making gains in one coactive has a butterfly effect on the others. Share on XIn a previous article I wrote, I discussed some of the theories and bullet points behind non-linear skill acquisition, one of which is the idea of affordances. Affordances are fairly simple to understand and are basically the opportunities for action that an athlete perceives in his environment. If a running back sees an open hole at the line of scrimmage, he now has an affordance available to him.

Well, affordances are not just based on what the environment provides, but also on what the athlete perceives himself capable of doing. So, by getting faster, a football player can spread his newfound confidence over into his technical abilities and tactical awareness. Here are some examples:

- A defensive back who has the responsibility of covering a deep zone of the field might feel more confident in creeping up near the line of scrimmage to hide his true intentions, knowing that he has the speed to bail out and still get to his zone in time.

- A mobile quarterback might not be flustered at all by a pass rush because he feels confident he can escape outside the pocket and still make a play with his speed.

- An offensive lineman might pull around the edge with more tenacity knowing that he can easily keep up with the scraping linebackers and prevent them from getting to his ball carrier.

- A running back might see an open hole and think “end zone” rather than just “first down.”

This butterfly effect of training speed trickles over into maintaining health as well. When looking at the physics, there is virtually no exercise outside of sprinting that exposes an athlete to the same combination of power, speed, elastic recoil, rhythm, coordination, and more. There’s a reason that sprinting is often referred to as the most intense activity the human body can produce. If athletes understand the basics of sprinting safely and efficiently, they can prime their bodies to build resiliency.

The basics of sprinting safely and efficiently help athletes prime their bodies to build resiliency. Share on XConcepts in Acceleration – Lessons from ALTIS

My mindset as it relates to linear sprinting has been heavily influenced by the folks down in Phoenix at a wonderful place called ALTIS. At the forefront of ALTIS are coaches like Dan Pfaff, Stu McMillan, and Kevin Tyler, who bring extensive experience and practical application in coaching elite track and field athletes from all over the world.

When visiting ALTIS or going through the education courses on their website, you quickly discover that they aren’t fully bound to traditional training theories and bring a lot of original thinking to the world of getting faster. In particular, I really appreciate their approach to using “motoric words”; that is, using certain words and cues to invoke a feeling in the athlete rather than just spitting out a body position. As an example, rather than telling an athlete to “arch the back” or “lift the knees up,” we can start using words like “drive”, “punch,” and “bounce” to give the athletes better context for understanding execution strategies.

Stu McMillan uses some fairly uncommon phrases to explain to his athletes what he wants to see. He talks about pressure and power, rather than saying “force into the ground,” to help the athletes understand they should press the ground away rather than stomp in an attempt to apply more force. He might discuss rhythm and timing to help athletes comprehend when foot strikes should occur at different speeds or body angles. Rather than telling somebody to “have good form,” he might explain what shape to display while achieving gradually more elevation on each step of acceleration. My favorite is how he doesn’t use the word “relax,” but instead uses the words patience and peace to help his sprinters remain at ease and let their performances unfold1.

Speed as a Fluid, Harmonious Whole

This quote from the ALTIS foundation course really sums it all up nicely: “Athletes should be thinking about the expression of speed as a fluid, blended activity – with an execution from start to finish which manifests itself as a harmonious whole, irrespective of the distance being covered.”1

This philosophy can be diluted down to three basic pillars of acceleration that are all interdependent:

- Projection: Projecting with appropriate force from the first step to the last. Too much or too little force will negatively affect the overall rhythm of the acceleration, as well as disrupt the smooth rise in the center of mass.

- Rhythm: Increasing the frequency of each step over the course of the acceleration distance. Shorter sprints (i.e., 40-yard dash) will require a faster change in rhythm than longer sprints (i.e., 100-meter sprint).

- Rise: Raising the center of mass slightly with each step of acceleration until fully upright. Appropriate projection and rhythm will lead to a smooth rise in the center of mass, like a plane taking off into the air.

So, my interpretation of this information is that any time we are training for linear acceleration performance, we are focusing on projection, rhythm, and rise. They are present at all times in unloaded sprinting. However, particular drills can emphasize some over others:

- Resisted sprinting emphasizes horizontal projection and the application of pressure and power.

- Variations of dribble runs can develop rhythm and timing when in the upright sprinting shape.

- Buildup runs can help athletes understand the smooth connection between rhythm and rise.

The ability to accelerate is a cornerstone reality of any field-based team sport, and American football is certainly no different. If we are training to enhance the absolute output of acceleration, it is important that we use sound principles. Similarly, just because our players aren’t powerlifters or Olympic lifters doesn’t mean they shouldn’t execute sound principles and mechanics when lifting.

What About Top Speed?

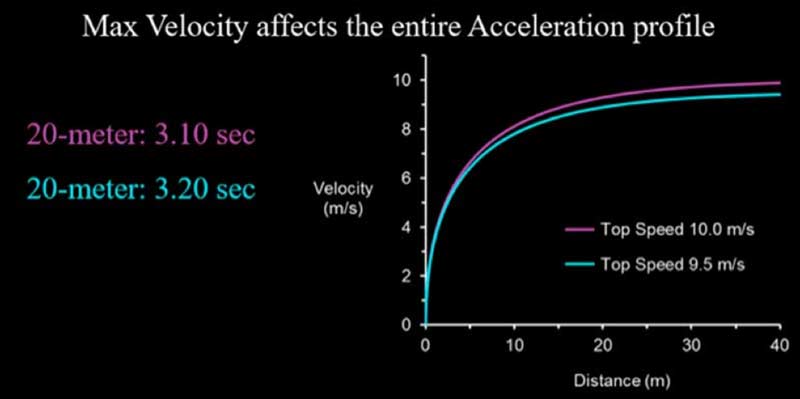

Top speed (also referred to as maximum velocity) will determine the absolute limit of how much speed a player can generate. I won’t touch too much on top speed here because I have gone in depth on this topic previously on SimpliFaster and lent support for its development by referencing the work of Dr. Ken Clark. To sum up significantly, there is a positive correlation between the level of maximum speed that a player can hit and his ability to accelerate at any given distance. I have reposted the diagram used in my previous article to illustrate this point.

As you can see, even just a 0.5 meter-per-second (m/s) increase in top speed can result in a difference of a tenth of a second in a 20-meter sprint and even greater differential at longer distances. That tenth of a second could mean the difference between being drafted or not, receiving a scholarship or not, or saving a touchdown or not.

Charlie Francis and CNS Intensity

It seems almost every team sport preparation specialist that has looked into speed training has come across the work of Charlie Francis. I know that Francis influenced me, and shaped a lot of my early views on how to prepare for speed. What I really took to heart is that we are simply not sprinting enough if we expect to be fast. His work also taught me to find out more about the central nervous system (CNS) and ensure not to overwork it.

What I really took to heart from Francis is that we aren’t sprinting enough if we expect to be fast. Share on XFrancis developed an approach known as high/low sequencing, whereby days of high-CNS intensive work (i.e., sprints, Olympic lifts, jumps, etc.) are alternated with days of low-CNS intensive work (i.e., aerobic work, upper body lifting). He explains the rationale behind this approach, stating that it takes about 48-72 hours for the CNS to recover from intensive work, and only 12-24 hours to recover from low-intensive, or extensive, work4.

As a note, high intensity in this case refers to big time activation of the body’s nervous system, which can only be achieved by pushing the body’s limits of explosive power. This is different than high-intensity cardiorespiratory work, which focuses on the power of the aerobic system. Both might be described as “high-intensity,” but for the purposes of this article, when I say “high intensity” I refer to CNS intensity rather than aerobic intensity.

Are Any Football Players Actually Fast?

Charlie Francis stated that novice sprinters have a much harder time exhausting their CNS. Their outputs are just not high enough to really trash them. Instead, excessive volume will likely lead more to structural risks like excessive muscle fatigue, soreness, or the potential of pulled muscles and strains. So, volume should still be kept in check, but it’s possible that the CNS is not being drained quite as much as we might expect.

If we consider what Francis describes as a “novice” sprinter, we start seeing comments like the following4:

- Lacks basic technical skills that relate to sprinting.

- Does not generate nearly as much CNS fatigue as a top sprinter.

- Should see consistent initial drops in sprint times as speed potential unfolds with training.

- Needs more focus on general fitness qualities (strength, power, mobility, etc.).

- Tends to decelerate quickly on longer sprint efforts, thus able to see greater speed gains by improving top speed before focusing primarily on starts.

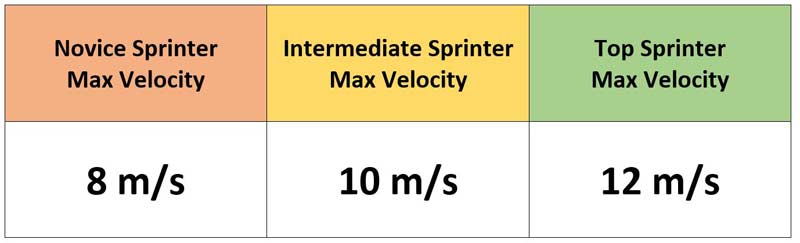

These comments sound an awful lot like they’re describing most football players learning how to improve their linear sprinting speed. In addition, Table 3 shows some of the maximum velocities, in meters per second (m/s), associated with what Francis refers to as beginner, intermediate, and top sprinters4.

Using the work from Ken Clark, we can objectively look at what this entails. Clark published a paper for the NSCA in 2017 titled “The National Football League Combine 40-Yard Dash: How Important is Maximum Velocity?” This article presents the mathematics to calculate modeled maximum velocity (top speed) from measured 40-yard dash times.

According to this math, a football player would have to run around a 4.37-second 40-yard dash to achieve a correlated velocity of 10 m/s. Any football scout will tell you that this is a blazing fast time for a football player. But is it blazing fast in the context of human ability?

Let’s consider the current NFL Combine record holder John Ross, who ran a recorded 4.22-second 40-yard dash. His associated velocity based on the math reported by Clark would be around 10.35 m/s. Fast for a football player? Undoubtedly. Fast compared to a top sprinter? Not even close.

Maintaining Perspective for Football Players

So, even the fastest 40-yard dash time ever recorded at the NFL Combine in Indianapolis would be considered “intermediate” in the world of sprinting. Now, I must state that 40 yards might seem far to some, but it is not a relatively far distance compared to events like the 100-meter sprint (which converts to about 110 yards).

Some players have more speed than their 40 times represent, as the 40-yard distance is just not enough room for them to continue accelerating to their true top speed. Tyreek Hill is a great example. According to Wikipedia, he ran a 10.19-second 100-meter sprint in 2012, which should put him close to a max velocity of 11.5 m/s. Hill is widely considered the fastest player in the NFL—but even with his 100-meter time, he STILL would not be considered a “top sprinter” in the world of track and field.

It seems that, at best, football players will only achieve a relatively intermediate output of speed no matter how much they develop. Let’s also consider the weight room in this regard: Are we going to have top-level powerlifters or Olympic lifters on our football team? Likely not. Again, at best we will probably see beginner-to-intermediate levels of output when compared against the best in the world.

Let’s be real about this though—this is FINE. Football is a team sport that is based on using specific tactics and techniques to get a higher score than your opponent. It’s quite literally NOT based on the absolute outputs of any particular movement. The only thing that matters is doing your job and doing it with enough skill to help your team win the game. That’s it.

Football is quite literally NOT based on the absolute outputs of any particular movement. Share on XHowever, while speed work might not be draining a football player’s CNS as much as it might for a high-level sprinter, we should also keep in mind that CNS fatigue will accumulate from other factors of football practice such as technical and tactical training. While we might be able to get away with more consecutive exposure to high-CNS training elements in the off-season, we still must be careful not to do too much on any given day.

Rethinking High/Low Sequencing

So, as I understand it, we won’t have the fastest, strongest, or most powerful people in the world playing on our football team. Therefore, it’s my belief that the focus needs to shift away from constantly chasing higher outputs and be put instead on developing the skills of movements like sprinting, jumping, or lifting, and letting the outputs happen organically. Two quotes from two great track coaches support this notion:

Charlie Francis: “I would be careful of the concept of ‘trying’ to run at 100%. If you run smooth, things will often sort themselves out, if the technique is good.”

Stu McMillan: “Coordination…rhythm…timing…balance…posture…elevation…These are the things that are truly the prime determinants of speed.”

I like to believe that skill is improved through high-quality exposure to the necessary stimuli to invoke change. As Dr. Kelly Starrett says in reference to how people move throughout their lives, “Practice makes permanent.”8

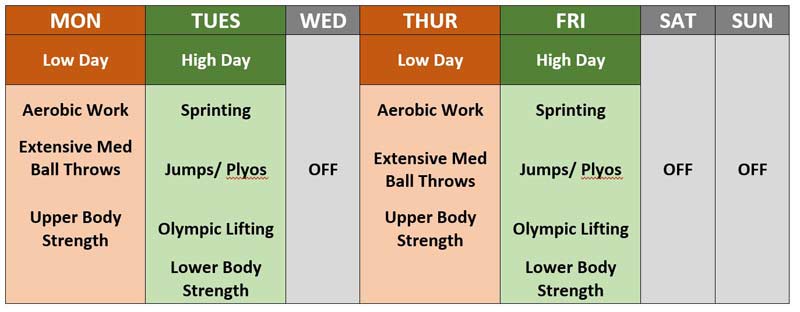

Most strength coaches I know who work in the private sector or in the college setting get four days to work hands-on with their players. I also know that a lot of strength coaches try to adapt Charlie Francis’ high/low model. Thinking they absolutely must follow a high day with a low day, they might end up with something like Table 4.

This was my exact template a few years ago. After thinking about it more, I realized a major issue: it only devotes two out of seven days to enhancing the skill of sprinting. With football players, it’s likely that they need more exposure to sprinting in order to foster the growth of speed as a skill.

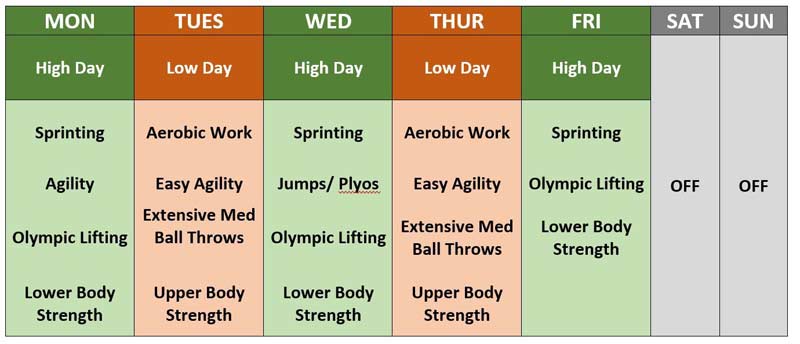

On his website back in 2014, Derek Hansen provided a theoretical template for utilizing a high/low approach with American football players over a five-day training period. If strength coaches have a system where they can access players for five days’ worth of training sessions, then this seems to be a really nice balance that allows for at least three days of high-intensity CNS work and naturally builds recovery into the program. Table 5 shows a rendition of Derek’s theoretical training week5.

My Solution

The fact is that most strength coaches work with a four-day training week and are faced with the challenge of having to build very explosive athletes while ensuring that they don’t fry them from a CNS standpoint. My solution has been to simply expose my athletes to some sort of speed and high CNS stimulus every training day while managing volumes with a “micro-dosing” mentality (stay tuned).

In the context of American football, I believe that constant speed exposure may be warranted. Share on XOne of the criticisms that Charlie Francis makes about having more frequent speed days is that it does not feature a “wave” progression and results in constant exposure. But when I consider the context of American football, the players will need to sprint at any given moment, on any given day of practice or during games. Therefore, in the context of football, I believe that constant speed exposure may be warranted for three primary reasons:

- The speed outputs of football players are drastically lower than top-level sprinters, enabling them to train in more intensive environments more frequently, as long as volumes are accounted for.

- Greater exposure to high-quality sprint training can enhance the skill acquisition of getting faster.

- Football players must have the capacity for explosive efforts at any given moment, all week long during the season.

This is my interpretation and my thinking, which may be different than yours and that’s okay. But I will provide my most-recent general template for high school and college football, showing the field work in combination with weight room work in the off-season.

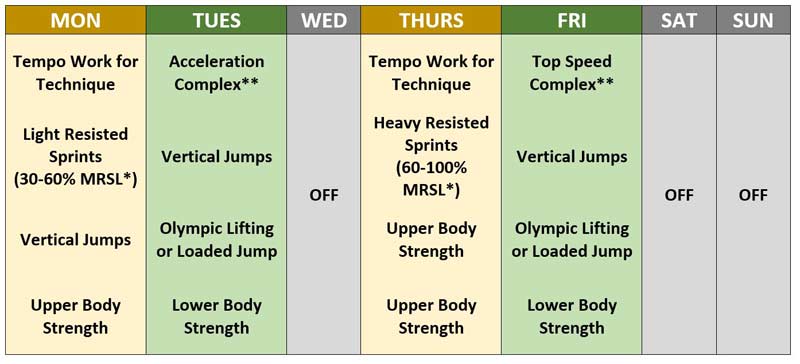

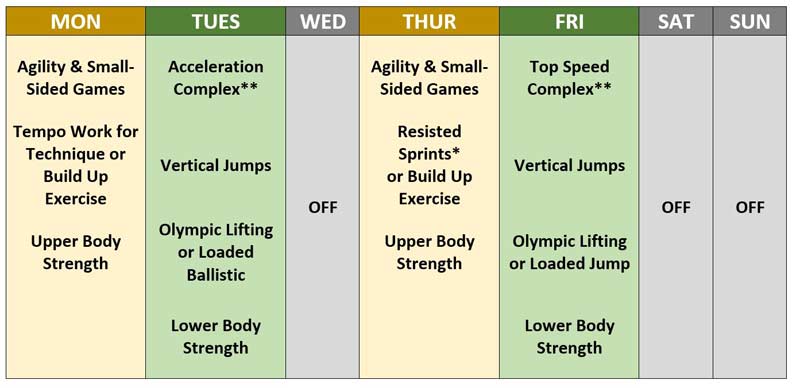

Table 6: My high school football off-season general training template, which shows field work in combination with weight room work in the off-season. *MRSL = Maximal Resisted Sled Load and can be understood by reading George Petrakos’ articles here and here. **Explained later in the article.

In these templates, four out of seven days are devoted to enhancing the skill of sprinting. The “off” days naturally build in three “low” days by default—the players are typically not engaging in required physical activity on these days and might engage in rest or recovery-based protocols. If we give them too many “low” days, as in Table 4, then they spend the majority of the week in a more down-regulated state, which will make the transition to in-season or spring ball much harder.

Micro-Dosing: Saving the Nervous System

A template is really nothing if we don’t consider the volume being performed within it. In Key Concepts Elite Edition, Charlie Francis gives an example of Ben Johnson averaging around 500 meters of total sprint volume in a speed session. Considering that Ben Johnson was clearly a top-level sprinter, the effects on his CNS after 500 meters of speed work would be very high in comparison to a football player. If Johnson performed three speed sessions a week using a high/low sequence, this volume would result in around 1500 meters a week.

Let’s also keep in mind that sprinting is sport practice for a sprinter. Much as a sprinter needs higher volumes of sprinting, powerlifters and Olympic lifters need more “practice” volume as well. Football players are not sprinters, powerlifters, or Olympic lifters. They are football players. Therefore, our goal should be to find the LEAST amount of sprinting, Olympic lifting, and strength training that will still yield positive results. This allows us to free up more CNS capacity for training aspects of the game like practicing positional skills, gaining a deeper understanding of the game tactics, and maintaining a healthy psychological state of mind. In the off-season, this means achieving deeper adaptations from representative learning drills and small-sided games or 7-on-7s.

Determine the LEAST amount of sprinting, lifting and strength training that yields positive results. Share on XTo bring up Derek Hansen again, he wrote an article back in 2015 discussing the use of “micro-dosing” for speed work during the football season to maintain a speed stimulus within the week of sports practice6. The article touched on the idea of performing a small handful of sprints to conclude the warm-up before practice, and how this can help maintain exposure to speed throughout the season. The concept ties into finding the minimal effective dose to see results but not excessively add to fatigue.

This became my journey for all forms of preparation for my football players. Where could I minimize volumes of general physical training while capitalizing on the most important aspects of performance?

The Needs Analysis: Filling in the Holes

High school players are exposed to plenty of game-like stimuli almost all year round with the upswing of 7-on-7 tournaments and collegiate recruiting camps that feature 7-on-7 situations as well as 1-on-1 situations. As stated previously, my goal for these kids is to get them as fast as possible in the 40-yard dash to help them get recruited. So, when we have our speed-dominant days (Tuesdays and Fridays in Table 6), I want to do my best to ensure that they feel focused and ready to commit to developing acceleration skills. I also don’t want them to perform too many repetitions of sprinting in the session, where quality starts to deteriorate.

For the college guys, they have already been recruited and must now acknowledge that playing the game and becoming a solid contributing player to their team should be paramount. However, we all know that college players are still largely scouted based on their ability to run a fast 40-yard dash. So, they need some exposure to representative learning in the form of agility training and small-sided games to enhance their technical-tactical skillset. However, they must also continue to devote some time to ensuring they reach a minimum performance threshold in speed, power, and strength if they expect to make it to the next level.

Team sports are incredibly complex, and training for them becomes a bit of a jigsaw puzzle. As Fergus Connolly talks about extensively in Game Changer, team sport athletes are very much creatures of habit. To this end, if I can find a volume range that works to enhance performance but not overload the system, then I can theoretically maintain this volume range while the players’ skill improves and training becomes more potent through a rise in intensity rather than always tweaking reps or sets. The players’ minds and bodies can become accustomed to knowing when certain stimuli will occur and approximately how much effort will be put into each workout. As long as we continue to enforce quality over quantity, we should start seeing improvements in the targeted skills.

My Volume Guidelines

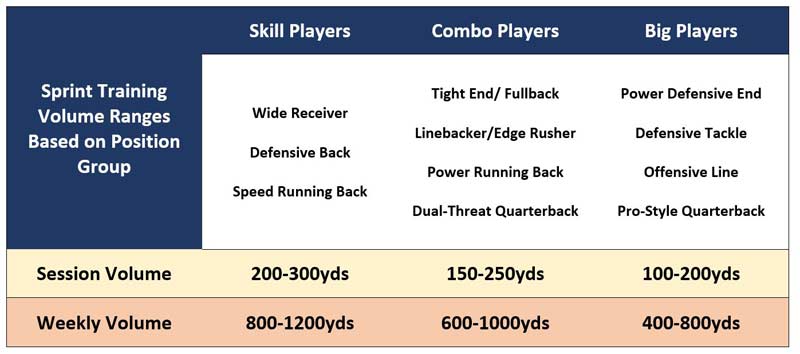

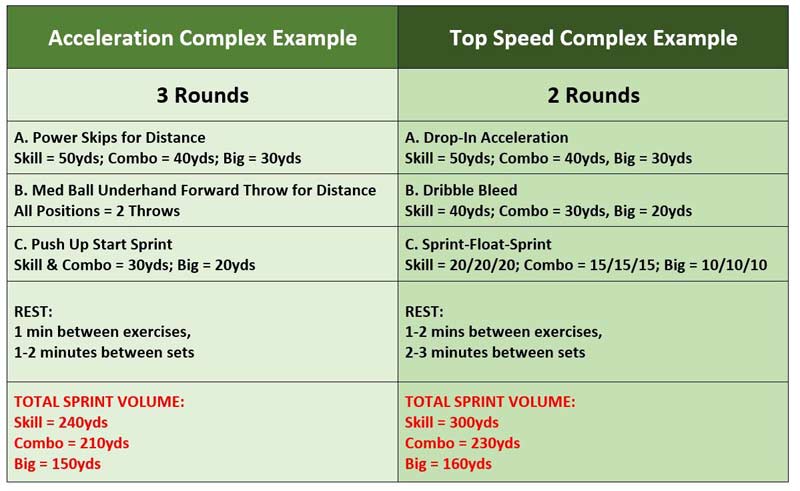

As far as direct speed training is concerned, I have seen some nice improvements from using the volume ranges shown in Table 8, listed by position group.

Cyclical drills like skips for distance or bounding are also added into the volume (total yards) for the field work, but broad jumps and throws are not. I believe more volume of cyclical activities in relation to explosive jumps will positively influence speed gains, so I make cyclical activities and sprint variations the priority.

When all is said and done, my athletes will typically only perform about four to six total sprints for the workout (with about one to three more done in the warm-up period). Since speed is present every day in some form, we really don’t need to do that much, especially if we want to keep quality high. Days that feature sprint testing will always fall on the lower end of total volume ranges.

Position will determine how far each sprint effort is in terms of distance. This affects total volume, so that linemen can perform the same number of repetitions as skill players but not travel as far. For example, on a testing day, a skill player might perform three 40-yard sprints to achieve a volume of 120 yards where a lineman might perform three 20-yard sprints to achieve a volume of 60 yards.

Examples of Drills and Protocols

In my program, I focus on sprinting as a skill by using complexes to develop my football players. My goal is to expose players to different concepts of acceleration and horizontal power so they harness skills with which they become very familiar but continue to refine over time. I alternate between using complexes and testing so that the psychological stress associated with testing days starts to diminish and I can track changes as they occur throughout the year.

Speed-Power Complexes

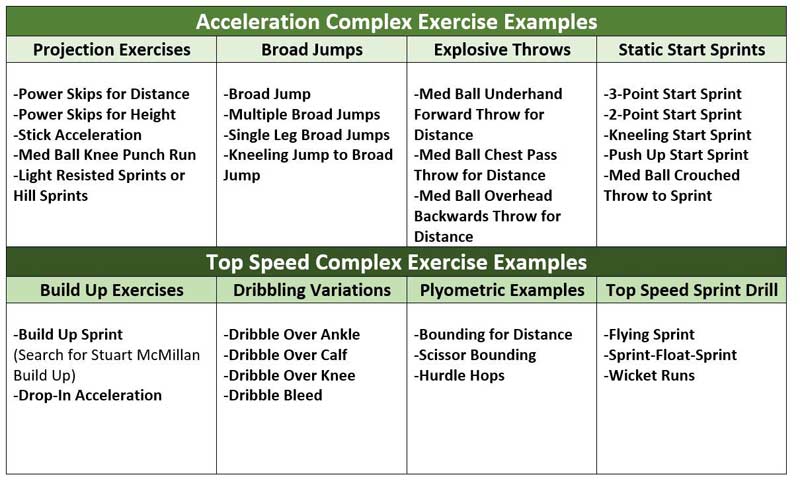

I love speed-power complexes for a couple of reasons. For one, I find that they help keep football players engaged because players tend to enjoy variety. In my experience, moving from one exercise to another helps them dial in for that particular moment and then they are stimulated by a new task afterwards. The other reason I enjoy speed-power complexes is because they challenge the football players to address different concepts of acceleration.

For example, taking an athlete’s arms out of the equation with a stick acceleration or while holding a medicine ball requires that they find a way to brace their trunk appropriately and find more power in the leg projection. There is also a potentiation effect as the first two exercises attempt to set up the final exercise in the complex where it’s all “put together.”

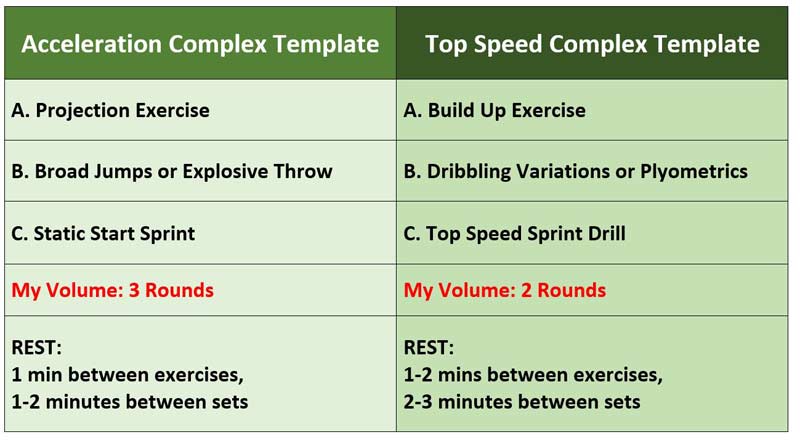

In my programming, I break up the complexes into two primary templates: Acceleration Complexes and Top Speed Complexes.

To keep this article from being incredibly long, I want you to know that all the exercises listed below are “searchable” on internet video platforms. I have ensured that the title of each exercise is, indeed, “searchable” so if any reader is unfamiliar with an exercise, a simple internet search will reveal the answer. I have uploaded some clips of my athletes performing some of these drills on my YouTube channel as well. Keep in mind that there are certainly more exercises that can fit into each category.

How I Test Speed

I typically test sprint performances in two-week cycles. So, I perform two weeks of speed-power complexes where no timing is done at all. Here, the focus lies in the development of skill and recharging the athletes’ focus. Then, for two weeks after that, I swap out the speed-power complexes in favor of some sort of sprint test.

I typically test either two- or three-point sprints for 20-30 yards if I want to get a measure of progress on acceleration, and I love using the flying 10-yard sprint test to measure changes to top speed. The 40-yard dash is used sparingly and I tend to stay away from it until I feel comfortable that the athletes are psychologically ready to perform a skillful sprint and not throw everything by the wayside just to get a decent time. This takes a lot of patience and practice. When timing 40s, I set up a fully automatic timer (FAT) and then I also hand-time it and record both times just to have some different vantage points.

Speed Is Great, but the Game Determines Everything

The major drawback of using 40-yard dash times and 100-meter sprint times as prime determinants of a prospect’s grade for recruitment is that the context does not match what really happens in the game. Wouldn’t common sense seem to say that coaches should look for players who play fast in the game, not just perform well on a linear sprint assessment?

It really all comes down to an athlete’s limiting factors. Simply stated, these are factors that limit a player’s ability to perform at a higher level. Limiting factors can exist in any of the four coactives: physical, psychological, technical, or tactical. In addition, when assessing limiting factors, the most sensible approach for a coaching staff is to identify them within the context of the game, not just in a closed testing environment. In other words, the game determines everything about how we should prepare football players.

The game determines everything about how we should prepare football players. Share on XPerforming a 40-yard dash is a skill, as is performing a 1-repetition maximum barbell squat. If a player is not familiar with the particular skill, there’s a good chance he won’t perform too well on it, despite his potential. There are plenty of players who are “ballers” on the field but don’t seem to test very well in combine-based activities. The context is different. Also, consider the players that absolutely crush the combine drills from practicing them over and over, but neglect the technical and tactical skill preparation of football and struggle to replicate these outputs in the context of the game. Of course, the most promising prospects (from a physical perspective) are the ones that both play at a high level and stand out at combines.

To me, it seems a big risk for a coaching staff to recruit solely based on sprint times and how a player performs in closed drills at a camp or combine. The complexity of the football game far exceeds any activity in these camps or combine environments. To understand how a player operates within all four coactives, we have to watch the player play the game. This idea is probably best summed up in a quote from Bill Belichick in reference to how he believes players should prepare:

“We’re training our players to play football, not to go through a bunch of those February [combine] drills. Yeah, our training is football intensive. We train them to get ready to play and ultimately that’s what they’re going to do…in the end, they’re going to make their career playing football. We already know that with our guys, and we don’t have to deal with any of that other stuff. We just train them for football. I think it’s huge.”7

As much as I love speed, I love winning football games more. Share on XLater this year, Fergus Connolly and I will provide a detailed, systematic approach to how players and coaches can start preparing players for the context of football in our upcoming book, The Process: The Methodology, Philosophy & Principles of Coaching Winning Football.

For me, increasing 40-yard times is a necessary step to help players get noticed in recruiting. Training for linear speed certainly helps improve physical capacity, but the reality of football is that assessment and testing must consider all four coactives if we really want to effect change in the wins and losses columns. As much as I love speed, I love winning football games more.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

- ALTIS Education Web site [Internet]. Phoenix (AZ): ALTIS Education; [cited 2018 July 6]. Available from: https://education.altis.world/

- Clark KP, Rieger RH, Bruno RF, & Stearne DJ. The NFL Combine 40-Yard Dash: How Important is Maximum Velocity? The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2017.

- Connolly F. Game Changer: The Art of Sports Science. Las Vegas (NV): Victory Belt Publishing Inc.; 2017.

- Francis C. Key Concepts: Elite Edition. CharlieFrancis.com; 2008.

- Hansen D. Applying the “High-Low” Training Concept to American Football. Strength Power Speed[Internet]. 2014 [cited 2018 July 6]. Available from: http://www.strengthpowerspeed.com/high-low-training-football/

- Hansen D. Micro-Dosing with Speed and Tempo Sessions for Performance Gains and Injury Prevention. Strength Power Speed [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2018 July 6]. Available from: http://www.strengthpowerspeed.com/micro-dosing-speed-tempo/

- New England Sports Network Web site [Internet]. Watertown (MA): New England Sports Network; [cited 2018 July 6]. Available from: https://nesn.com/2016/02/bill-belichicks-advice-to-prospects-training-for-nfl-scouting-combine/

- Starrett K. Becoming a Supple Leopard 2ndEdition: The Ultimate Guide to Resolving Pain, Preventing Injury, and Optimizing Athletic Performance. Las Vegas (NV): Victory Belt Publishing Inc.; 2015.

Great article which an absolute must read in 2018! There was a time when “track” coaches were routinely thrown under the bus. The work that you’ve done, drawing on the previous work of Pfaff, McMillan, Francis, Clark, and Hansen illustrates that this was limited thinking at best.

Might be some pushback from the “Total Body” strength training crowd but that’s next in line for them to figure out.

Cam, great article came across this after a podcast. I know mentioned ways to monitor sprints.

What are the best apps or equipment for youth athletes to be monitored with?

Please let me know Thank you!

What is an example of a “tempo work for technique” workout?

Is this out in text? The Process: The Methodology, Philosophy & Principles of Coaching Winning Football.

Thanks!