For more than five years, Andrew Flatt and Mike Esco have conducted sports performance HRV studies on collegiate athletes, and they’ve teamed up with other colleagues to investigate American football. Their latest project involves monitoring HRV in collegiate football players during spring camp.

Different positions in football tend to have different levels of body mass and fitness, and therefore you might expect them to show different responses to training. Backs and receivers experience the greatest running demands and tend to be the leanest and fittest, while linemen require the greatest strength and body mass to win the frequent physical bouts, but don’t need to run as much. For this study, the researchers were particularly interested in seeing the effects of training load on the day-to-day recovery of each positional group measured using HRV.

The Investigation

During a four-week spring training camp, Flatt and Esco monitored 25 players over 14 training sessions. This consisted of three to four practice sessions and two resistance sessions per week, with Sundays reserved for complete rest. The player split was 11 backs and receivers (skill); nine running backs, linebackers, and tight ends (mid-skill); and five linemen.

The researchers derived external training load (Catapult total player load) from accelerometers worn by the players during the training sessions. They monitored internal load and recovery using the ithlete HRV Team System and finger sensor three days during Week 2 to create a baseline, and then on Saturday of the same week to create a post-training reading. Baseline changes were calculated from this reading, as well as the coefficient of variation, which these researchers have shown correlates with lower VO2 max and running performance.

Findings from the Data

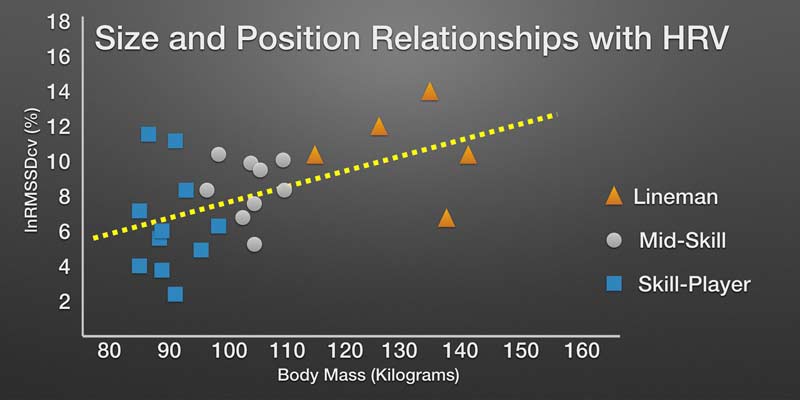

The researchers’ first discovery was that, as suspected, changes in HRV from baseline were dependent on playing position. The researchers saw a relationship between player position and internal load HRV data, allowing teams to profile each athlete better. How a team can take advantage of this will likely depend on the way practices are prescribed during the training week, an area in American football that is still embryonic.

Looking at all the data, body mass was a primary factor in determining the response to training loads, and work rate and type of work as well. As the athlete becomes smaller, the distanced covered increases, and contact usually decreases. Player load scores are a composite of all types of loading, including high speed running, collisions, and even jumping.

What It Means for Coaches

This study found a clear difference between the three positional groups in their ability to handle the high training loads imposed by the spring camp schedule. Linemen seemed to be significantly more vulnerable to high training loads, and found it more difficult to recover within a 24-hour period than the other groups.

Body mass was a primary factor in determining the response to training loads, says @SimonWegerif. Share on XThe authors theorized that the higher body mass, combined with lower aerobic fitness and greater reliance on short-term anaerobic energy production, contributed to higher levels of HRV disturbance in linemen. They also suggested that higher aerobic fitness might offer protection to this group of players. Finally, they concluded that short 60-second pre-training HRV readings are practical and offer useful information to coaches of elite American football players to help optimize training loads for players in different positions.

The strength of this paper is that it combined both internal and external measurements, and created a working model on how different-sized athletes who play different positions respond to practices during intense training periods. Coaches who choose to use the HRV response information can compare and contrast training load patterns easily and immediately.

Conclusions and Future Explorations

The study shows that a working strategy for the collection, analysis, and interpretation of HRV in American football is not only possible, it’s practical in a large team when short sampling times are used. The strength of the ithlete system is its ability to quickly capture data at team facilities or at home, and then provide guidance on how the athlete’s autonomic nervous system is responding. In the future, it is certainly possible that HRV readings will be used to help manage fatigue and reduce injury, now that the technology is practical and easy to use.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

I know Alabama has gotten a lot of attention and praise for what Matt Rhea and David Ballou have done for the program. With that being said, how far behind, if it’s something you can put into words, is a program like Ohio State in terms of their sports performance?

Honestly, from the small amount I’ve been exposed to (mostly camps) I’d say they’re quite close but I’m not sure I completely understand your question. Are you talking in terms of S&C? Performance building? Etc.