Every traditional Olympic weightlifting program looks inherently the same on paper. There is a combination or variation of snatch, clean, jerk, squat, push, pull, and common accessories; then rinse, wash, repeat. Intensities and volume prescriptions are based on the athlete’s competition schedule and how many weeks out they are from a meet.

This ideology of programming has worked for decades, and the beauty in this simplicity is that an athlete can train as long as they have a barbell and set of plates. But just as there is more to a basketball player than being able to dribble and shoot, a weightlifter needs more than just the snatch and clean.

In weightlifting, you have to play the long game. The only way to become more proficient in the lifts is through time and consistency. You have to be able to physically endure the high intensities and volumes to get stronger while still improving on the technical aspects of the lifts. If an athlete can’t endure the rigorous training density of a cycle, then frustration and lack of progress begin to set in. By providing the athlete with a better base to build from, we can avoid such stagnation—the whole is always stronger than one part.

GPP for Competitive Weightlifters

General physical preparation (GPP) gives an athlete the opportunity to step away from the barbell without crippling their training or suspending their overall goals. We can look at GPP as a phase in a program or as the accessory movements built into a more traditional weightlifting program. In either case, the overall themes of GPP are variability and durability.

We can look at GPP as a phase in a program or as the accessory movements built into a more traditional weightlifting program. Either way, the overall themes of GPP are variability and durability. Share on XAs a benefit, GPP supports athletes on a wide spectrum, from rehabbing injuries to developing a more athletic base. Training with alternative pieces of equipment forces the athlete to move differently, thus exposing some underlying weaknesses. Equipment variety (dumbbells, kettlebells, bands, medicine balls, etc.) can easily alter body position, load placement, and movement. This will keep training efficiency high and decrease the likeliness of plateauing due to years of adaptation.

Weightlifters are regimented in their training and are more likely to take time off due to chronic injury and overload—GPP can provide a solution to help heal a nagging injury or improve the athlete’s ability to withstand overall training density better through several cycles. The biggest benefits to GPP exercises, specifically those without a barbell, are to:

- Challenge the athlete in non-sport-specific movements and positions.

- Increase longevity and sustainability within the sport.

- Improve motor control and neuromuscular adaptations.

Non-Sport-Specific Movements

Weightlifting is predominantly a bilateral (with the exception of the split jerk) and sagittal plane sport. So, this is where the athlete is the strongest. These strengths often hide other deficiencies. Training unilateral movements will highlight weaker areas and provide the coach with more information on how to improve their athlete’s training and performance. This training will also help an athlete reduce the bilateral deficit effect, because training unilaterally will improve overall bilateral strength and power.

A common issue we see in weightlifting is an athlete not pushing evenly through both feet. We all know that every human has a stronger side and a weaker side, and when an athlete isn’t conscious of those asymmetries, it can lead to issues down the road. Broadly speaking, it can either lead to muscular compensation or create a technical flaw. GPP gives coaches an opportunity to include more unilateral work to help close any asymmetries between the right and left sides without affecting the overall goal of the training day.

GPP gives coaches an opportunity to include more unilateral work to help close any asymmetries between the right and left sides without affecting the overall goal of the training day. Share on XThe same is true for stepping out of the “sagittal box” and into more frontal and transverse movements. The human body is three-dimensional, so training solely in flexion and extension for the sake of the sport limits the athlete’s robustness and adaptability should something be thrown off during a lift.

Think about when you play Jenga: as you pull one block and place it on top of another, you make a crisscross pattern because that builds a stronger foundation. If you were to only stack the blocks in one direction, the game would never get far because the column wouldn’t have any true support from outside forces. The human body is no different. Our soft tissue structures are interwoven and all connected. If we aren’t training those cross sections to be durable, then we are limiting our athletes in their ability to grow and progress within the sport.

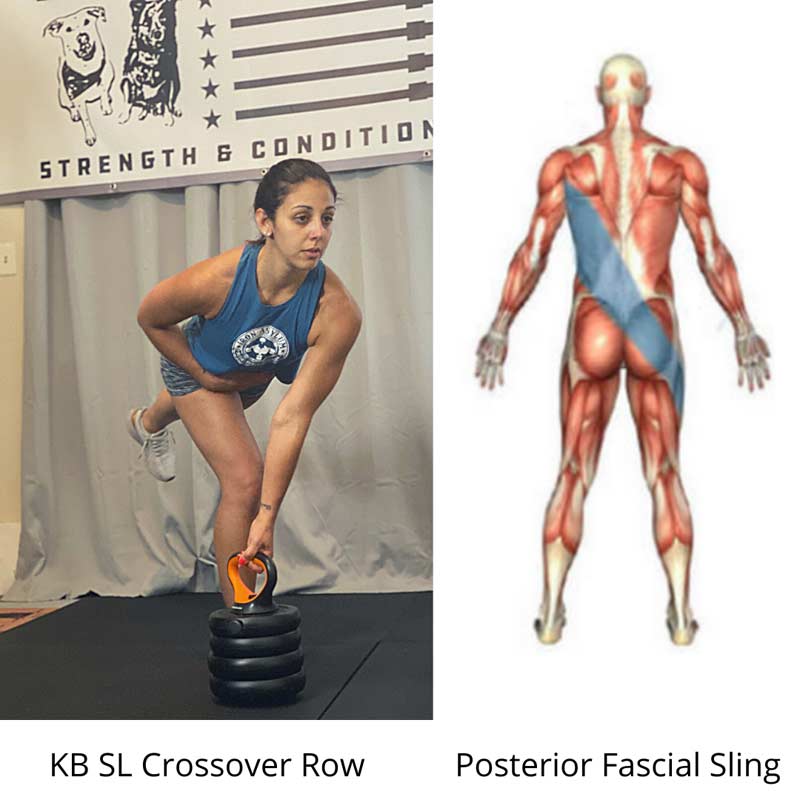

The KB SL Crossover Row is one of my favorite movements because it combines two common weightlifting accessories: the row and the RDL. Weightlifters need a strong back and posterior chain, and this movement checks all the boxes because the single leg crossover row takes it a step further with glute strength and stability on the stance leg and lat/upper back engagement on the opposite side (which, coincidentally, strengthens the posterior fascial sling).

Cue the athlete to “coil” around the hip of the stance leg to ensure they aren’t dumping their shoulder forward as the kettlebell reaches toward the ground. The spine and hips stay neutral, which also improves IR hip stability of the standing leg. Look to create variations from more traditional accessories, which will challenge an athlete and bring efficiency to the program.

Load Variation

Variability in training will also help avoid overuse and chronic injuries that creep in due to fatigue or the inability to tolerate programming. We see it all too often when an athlete has to take time off due to a chronic injury. They begin a cycle of PT and rehabilitation, and not only do they physically atrophy by not loading their body, but mentally their confidence and investment in training deteriorate because they feel like they are falling farther and farther behind. When a weightlifter’s sole purpose is to move more weight, being sidelined and relegated to band work and bodyweight movement is arguably more dangerous mentally than it is physically.

But what if it doesn’t have to be that way?

GPP can be utilized to stay ahead of these overuse injuries. Through strategic programming, the athlete can focus on building strength and technical proficiency.

Exercises often used in traditional rehab can be performed under load and viewed as prehab instead. Other exercises can give certain joints and musculature a break without completely eradicating an athlete’s training cycle. Load variation can either protect an athlete from incurring an overuse injury or allow them to continue training through an injury. In either case, we avoid a total sidelining of the athlete for an extended period of time.

The belt squat is a great way to load an athlete’s hips and quads without adding any additional compressive load or volume on the spine, says @nicc__marie. Share on XOne common ailment among weightlifters is low back pain. This shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone due to the nature of the sport’s training intensity and the amount of pulling scripted in their program. The belt squat is a great way to load an athlete’s hips and quads without adding any additional compressive load or volume on the spine. The athlete can continue to squat heavy-ish and often without aggravating or straining the spine any more than it needs to be.

Video 1. Athletes can use belt squats as a substitute for back squats if training through an injury or as an accessory on days that back squats and front squats aren’t programmed. The belt squat also allows the hips to work through a deeper range of motion.

Mobilizing and strengthening that deep hip flexion shown in the above clip will prepare the athlete to better handle the dynamic load of the barbell when dropping into the bottom position of the clean or snatch.

Motor Control

An athlete should understand why GPP exercises are essential to their training. This autonomy creates buy-in and keeps them engaged. The Olympic lifts require a lot of mental focus, so when it comes time for accessory work, athletes often mentally disengage. But we never want our athletes to “go through the motions.” There should be intention and cueing behind each exercise. Having the benefit of understanding why they are doing something will produce better results.

Neurologically speaking, mental engagement or “intention” isn’t the only way the brain is involved. Two less obvious skills that are critical to a successful lift are proprioception and spatial awareness. Band loading is a simple yet effective way to challenge motor control and stability in major joints. We can utilize tempo and speed work, incorporate positional holds, and add band chaos for progressions.

Video 2. The Russian Lunge is an example of taking a rearfoot elevated split squat and adding a motor control component. By placing the back leg on a suspended heavy band, the athlete requires a greater demand of front leg stability, which emphasizes strength on the front leg’s hamstrings and glutes with posterior leg control.

In order for an athlete to have strong single leg balance, they have to understand how to ground or “melt” their foot into the floor to feel that connection. Foot/ground connection is a vital underlying part of weightlifting in terms of weight distribution, ground force production, and drive into triple extension. Intrinsic foot strength is also a strong predictor for dorsiflexion, which is critical in the bottom position of both the clean and snatch.

This exercise is also a good place to cue the intention and importance of the foot. As with each of these movements, don’t be afraid to build in progressions to challenge your athletes by holding equipment in different positions, such as:

- Overhead

- Single arm

- Goblet hold

- Barbell front rack

- Other variations

Below is a chart of some go-to exercises, and a playlist with demonstrations of each exercise listed is available here. I like to think outside of the platform and challenge my athletes to try things that are different. I want them to get out of their comfort zone in order to become a better athlete mentally and physically, and GPP/accessory movements are a great place to start.

I want athletes to get out of their comfort zone in order to become a better athlete mentally and physically, and GPP/accessory movements are a great place to start, says @nicc__marie. Share on X

There are infinite combinations of position/load/band placement for each of these movements to progress and add variety. Alternate from bilateral to unilateral, change the plane of movement, adjust load positioning, and add oscillating load. Some of these movements are sport-specific and others help improve positional work and limitations that are compensated for with a barbell. Regardless of how you create variability, it will expose weaknesses within your athletes to help improve their durability and longevity in the sport.

From Adaptability to Durability

The amount of GPP an athlete needs will be dependent on their training history, current sport season, and injury history. Not only do weightlifters benefit, but clientele in the general population who are interested in getting into Olympic weightlifting can look at these movements as a way to help develop the positional and muscular strength needed to start.

Athletes and the general population will always see a benefit to these movements, as long as they are presented and performed with proper volume, load, and intention. As coaches, we strive to keep our athletes healthy and continuously progressing over time. By incorporating more non-barbell exercises as a form of GPP training or accessory work, we can provide a better foundation for our athletes. Don’t be afraid to try something different and force the athlete to move and adapt. The more adaptable they are, the more durable they will become.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF