An athlete having difficulty pulling under the bar is a common problem that every coach has seen at one point or another. Sometimes there is a mental barrier, and the athlete is simply afraid to drop under the bar. But I believe this fear mostly stems from a physical limitation—in technique, mobility, or stability—that hasn’t been addressed. Bad habits can develop over time as a way to compensate for a physical limitation or as a way to overcome a misunderstanding or lack of development in the technique. In either case, if this issue goes unaddressed, it can lead to general frustration and plateaus, along with compromising the overall lift/capacity that the athlete can perform.

When an athlete is afraid to drop under the bar, I believe this fear mostly stems from a physical limitation—in technique, mobility, or stability—that hasn’t been addressed, says @nicc__marie. Share on XThe snatch and clean are taught as three phases: first pull, second pull, and third pull. In the third pull of the lift, the athlete actively pulls themselves under the bar and into the receiving or catch position. The athlete meets the bar at its highest point relative to the weight on the bar and the amount of explosiveness generated by the athlete in the second pull. The athlete’s job is to move under the bar with speed and intention. It is important for the athlete to understand and remain connected with the barbell. If the athlete is unsure of how high they are driving the bar upward, then they will inevitably mistime their pull into the catch position.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9053]

The height of the receiving position varies between the snatch and the clean. In the snatch, we want the athlete to find their bottom position, whether it be in a power snatch or full snatch, in order to lock their arms and maintain a stable overhead position. The bar will land over top of the athlete’s center of gravity, creating very little barbell dissonance for the athlete as they accelerate into the bottom position.

In the clean, the catch position of the barbell is forward of the athlete’s center of gravity in the front rack position. Although the same rules apply as the snatch, if the athlete races down into the bottom position before meeting the bar, then it will crash on top of them and potentially “spit them out.” In other words, when the athlete tries to find the catch position of the lift, the bar hits them so hard on their front rack that it bounces forward off of them and shoots the athlete back. Check out this clip of Phil Sabatini for reference.

In order to begin improving this phase of the lift, a coach must make sure the athlete can safely get into the bottom position. Athletes should begin with the overhead squat for the snatch and the front squat for the clean. If an athlete is incapable of demonstrating these movements proficiently, then we know there is a mobility or stability issue somewhere causing the limitation. However, in this article I want to focus on the technique side of pulling under the bar and how to improve this phase.

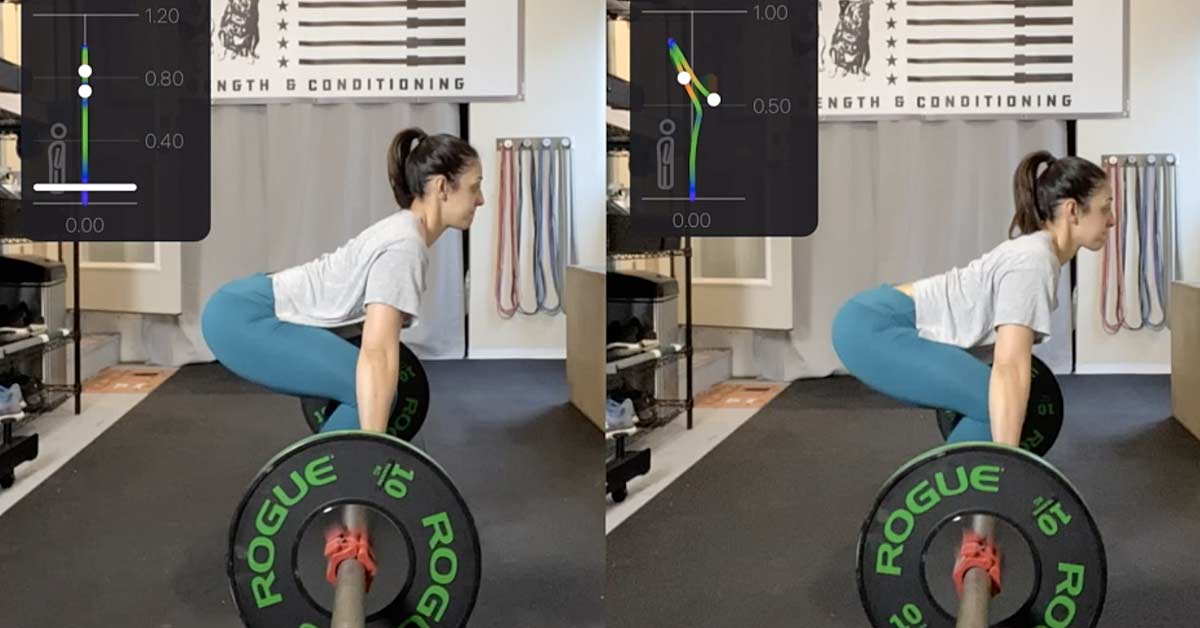

Video 1. Proper balance is a key to the snatch and safely getting into the bottom of the lift.

Let’s say an athlete is mobile enough to get into the bottom position and stable enough to receive the bar both overhead and in the front rack. What next? Lack of explosiveness in the drive or second pull phase of the lift will limit the height of the barbell and prevent the athlete from having a chance to get under the bar. An aggressive pull is necessary to maintain a close bar path and allow for a quick change in direction from the athlete. The speed of an athlete, or lack thereof, is the biggest factor that limits the athlete’s ability to quickly change direction and transition under the bar as it moves upward. But without the other two components, the athlete won’t even be able to consider the speed at which they pull under the bar.

Select drills for your athletes that will address their weakest point and keep in mind that may also correct other faults along the way, says @nicc__marie. Share on XIt is important to note that different drills can help fix more than one fault. As we begin to look at a variety of drills in the next few sections, remember that weightlifting is cause and effect. Select drills for your athletes that will address their weakest point and keep in mind that may also correct other faults along the way. As a coach, if you are trying to isolate one particular fault, always provide a distinct focus or intention behind the drill.

Explosiveness

The second pull is the phase of the lift that demands an explosive drive of the bar, generated by the athlete. This becomes an issue for the athlete because a heavier barbell already limits its ascension. In this scenario, speed to pull under the bar won’t be a factor because there is simply not enough room for the athlete to get under the bar. There are two things to consider when this is a factor:

- Is the athlete cutting their pull too short and beginning the transition from first pull to second pull too soon?

- Are they losing their connection into the floor through their feet?

To address the issue of pulling too early, athletes can focus pulls, but it is vital that you express to the athlete the technique and purpose of the pulls as a drill to improve the lifts in order to get the best ROI for the movement. Pulls are a great exercise to overload the athlete and work on that explosiveness at heavier weights, along with preventing an early arm bend. If your athlete tends to begin that first to second pull transition too early, then more specific positional drills such as a snatch pull (BKN) (below the knee) or clean pull (AKN) (above the knee) are good ways to reinforce the timing of when to begin shifting the torso upright.

Video 2. Using snatch and clean pulls can help prevent early arm bend and establish proper weight distribution for executing the full versions of each lift.

An early arm bend will interrupt the athlete’s explosiveness because it will take the force out of the legs and into the arms too early. This is why I emphasize keeping the arms long in the pull. For more information on this, check out my other article, “To Bend or Not to Bend.”

Weight distribution is a huge factor in Olympic weightlifting in terms of bar path, position, and force production. If an athlete’s feet leave the floor too soon, it will affect their power and force production. Two of Newton’s laws of motion apply directly to this idea. The second law, Force = Mass x Acceleration explains that the weight and speed on the bar will determine force production. If the bar’s trajectory begins to shift horizontally, that will slow everything down, which will take away from the total amount of force. The third law, every action has an equal and opposite reaction, tells us that if our heels or toes come off the floor, then we won’t be able to generate as much force into the floor. In turn, we won’t receive as much force back to help move the bar.

Block work is a great way to reinforce connection into the floor and explosiveness in the drive. When an athlete works through their weaker positional variations, they can rely on downward momentum into the position to generate force. But block work forces the athlete to move the barbell from a dead stop. They have to feel the setup of the position and adjust their body to generate force.

Block work is a great way to reinforce connection into the floor and explosiveness in the drive… Block work forces the athlete to move the barbell from a dead stop, says @nicc__marie. Share on XThe height of the blocks will determine the amount of push required by the athlete to drive the body and bar upward through the triple extension position. Where focusing on better weight distribution means focusing on the knees or low blocks, reinforcing strong drive demands implies the higher the better. In a high block clean, the bar is already placed in the power position.

Most times, athletes feel as if they have no power to generate to move the barbell. If left uncoached, we begin to see a lot of torso movement to drive the bar. Intention is key: The athlete should feel their feet active into the floor and initiate a push down through the feet to drive the bar. In either case, block work helps to correct the first and second pulls of the lift in order to create a more optimal chance to master the third pull and successfully complete the lift.

Aggressiveness

Block work not only improves explosiveness, but it gives the athlete a stronger sense of positions and the power needed to drive the bar upward. Then the athlete can begin to use their arms. The arms shouldn’t bend until after the athlete hits triple extension. If the arms bend too early, well that’s a whole other topic for another time.

Once the elbows are ready to bend, they must be aggressive and synchronous to the body beginning to move under the bar. One of the best analogies I’ve ever heard was told to me by Coach Brenden Mcdaniel. He said, “You know how you bend your arms to pull yourself down a waterslide as fast as you can…this is like that except vertically.” In that moment, the timing and intention of the pull under the bar became so much clearer. It’s why the cue elbows up, body down has such a major benefit for athletes who are kinesthetic learners.

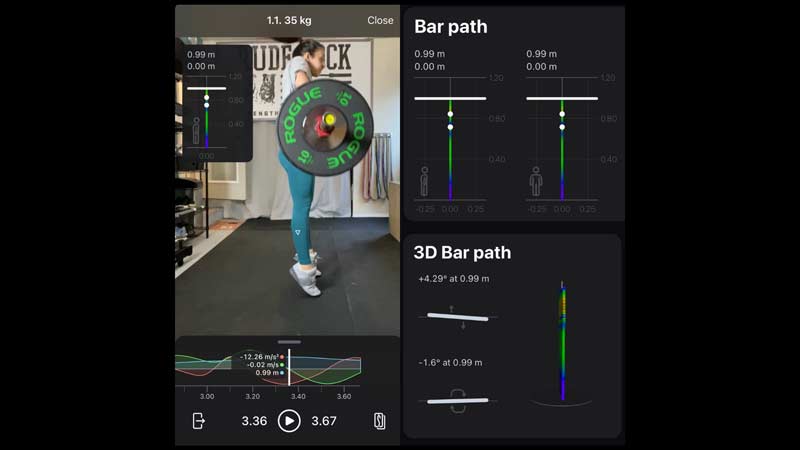

Videos 3 & 4. Bar path measurements for the clean pull and snatch pull via Vmaxpro.

Pull-unders are one of my top drills to emphasize the aggressiveness of the upper body coupled with the speed of pulling yourself down. The heavier the bar gets in this drill, the more crucial the timing becomes. I want them to feel the weight of the bar in their hands to emphasize the intensity needed to pull themselves down under the bar. The harder they pull, the higher the bar goes.

Remember, the intention still focuses on pulling the body down as the arms pull up. It is the opposition that we are working to emphasize in order for the athlete to better understand where the bar is during the turnover. The intentional aggressiveness of the movement will help the athlete become more cognizant of where the barbell is in space; then they can begin to focus on the timing and directional speed change.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9082]

Speed/Timing

Speed is demanded of the athlete as soon as the bar passes the athlete’s knees on the way up, and again as they begin to pull themselves down. Athletes will often fixate on the position and bar path as the bar moves upward and never increase their speed when it is time to pull down. The speed and ability to change direction and move under the bar is vital as the weights get heavier.

If an athlete spends too much time in triple extension, then it immediately affects the timing of when an athlete makes contact and drives the bar upward to when they begin pulling down. If the athlete doesn’t aggressively drive the elbows upward, they give themselves less time to move under the bar. Each of those two points mentioned earlier allows for the athlete to pull their hips down quickly.

Video 5. Performing “No feet” drills for the clean and snatch to improve speed and timing.

“No feet” drills are a great way to correct all of these issues, but the biggest thing I emphasize with “no feet” is the speed with which you have to rip down. When an athlete stops thinking about having to shuffle their feet out and down into the catch position, they can concentrate on driving the bar and not cutting the pull short. They will also be forced to drop down quickly because they aren’t getting the extra height provided from the ankles extended.

With “no feet” cleans and “no feet” snatches, the athlete should begin their setup with their feet already in their catch position. As they begin to pull down, they only have to focus on their hips coming down into their bottom position and their feet are already set in place. Fewer variables allows for better focus on the speed down into the bottom position.

Snatch balances are another great way to reinforce the speed and timing into the bottom position. The goal is to drive the bar upward as the body simultaneously moves down. Reinforcing this timing and the stability of the overhead position, especially at heavier weights than the snatch can be performed, builds more strength in the bottom position.

The more comfortable an athlete becomes at pulling themselves down and meeting the bar, the more the timing will improve, says @nicc__marie. Share on XThe more comfortable an athlete becomes at pulling themselves down and meeting the bar, the more the timing will improve. Consistency and intention at lighter weights will build a strong carryover to heavier lifts. With all things being equal, the height of the bar is always going to depend on the amount of weight on the bar and the ability of the athlete to move that weight.

An athlete having a strong understanding of where the bar is at all times and the intensity at which they handle the barbell will lead the way to proper timing, aggression, and speed of the third pull. Just like anything in weightlifting, there is never one answer; rather, a variety of ways to assess and address a situation that can lead to improvement in other areas. It is the job of the coach to understand where the athlete is having trouble and provide them with the right strategies to fix it.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF