[mashshare]

If you are an avid reader of SimpliFaster, you will notice the frequent reference to electromyography (EMG) studies throughout the blog’s articles. The goal of this review is to inform readers about the science and application of EMG experimentation. Not all readers will have the need to perform EMG readings on themselves or their athletes, but everyone involved with sports in some capacity should be aware of the requirements for measuring muscle activity.

The ability to understand EMG research and apply the science is a valuable benefit when making decisions on exercise selection and other choices in training and rehabilitation. This guide includes instructions on performing your own EMG experiments, as well as determining when you need additional instrumentation or expertise to analyze the collected data.

What Is Electromyography?

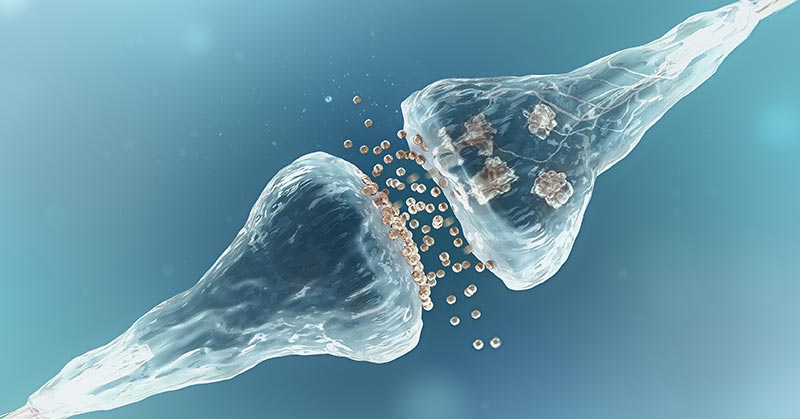

Electromyography is a measurement of electrical activity in the muscles during movement. EMG is used in both medical and research settings, and the data collected is valuable to learn what is happening with muscle and motion. Depending on the location of the muscle group, users of EMG will either perform surface data collection or, if deep muscles need to be measured, fine wires are used for intramuscular insertion.

An electromyogram records the signal strength to the muscle or set of muscles. EMG is an indirect measure of muscle force, since it’s only picking up the neurological activity during the movement, and not the direct muscle tension. Most instruments that measure EMG send the signals to a computer or other hardware tool to filter the data, so it can be displayed and analyzed later by a trained professional. A valid interpretation depends upon a strong knowledge of both movement science and muscle physiology, and other simultaneous measurements are taken to cross-validate and ensure confidence in the findings.

The Value of Internal EMG Data for Coaches and Sports Medicine

Performance coaches and sports medicine professionals have relied on research to provide clues and insights into the actions of muscles during sports tasks and exercises, whether for performance or rehabilitation. The arguments against EMG are not because of the science or technology, but the contextual design of the studies—the specific exercises and subject populations. If you have direct access to EMG instrumentation and can test your own athletes, it’s far more useful than depending only on external studies.

The application of EMG is not just for research. EMG is also an important tool for biofeedback during training and rehabilitation. In addition to quantitative feedback for the athlete while performing physical tasks or rudimentary rehab exercises, EMG is a great teaching tool. Clinical settings, as well as group training, rarely use EMG to assist the professionals involved, but new technology is streamlining the process and athletes are more engaged in their data now.

EMG technology has come a long way since the 1950s and 1960s, but it’s still the same tool when you strip away the newer innovations and get right to its core. The major difference is that the transmission of the data from athletes is wireless now, and the data can also synchronize with other sensors and instruments.

Whether you perform your own experiments or only read the experiments done in formal research, being informed on the nuances of data collection and interpretation is vital to understand what the information means. Coaches and sports medicine professionals can be tempted to scan through the materials and methods parts of studies and skip to the conclusions or summary charts, but they then risk missing the true results evident in the paper. Read the full study and even the citations at the end of a research paper. It is important to judge the data and the conclusion of the author(s) separately.

What Information Can EMG Provide to Professionals?

Nearly all of the studies that use EMG tend to be investigations into popular exercises in strength and conditioning or rehabilitation. Many landmark studies on sports tasks are very popular and have a large impact on other studies—an important ranking measurement in research—due to their value in revealing what is happening in athletic motion. Simply stated, training and rehabbing athletes can get a hint from EMG as to what is happening with the muscles involved in sport and what exercises could help prepare them for their particular sport.

EMG is not just about which muscles work the most during exercise; it provides a vast amount of information that can help everyone in sport solve problems better. For example, EMG can help measure the rate of force development (RFD), track coordination changes from beginner to advanced athletes, observe symmetry and asymmetry in gait, and even determine the effects of pain and fatigue on older populations. EMG provides a wealth of information that transcends sports and the field of physical therapy. Electromyography connects to other fields of study as well.

EMG is not just about which muscles work the most during exercise; it provides a vast amount of information that can help everyone in sport solve problems better.

Most of the arguments in support of investments in EMG education and equipment cite the ability to get more information than the naked eye can reveal. Another benefit is that the information is objective, so that everyone can agree on it and decide on an intervention. Dysfunctional muscles are not just a weakness or size issue (cross-sectional)—there’s often a less obvious factor that can’t be left to guesswork. The use of EMG on athletes in team or college environments adds another layer of confidence that what is being done in training and rehab is managed properly.

The Requirements for Collecting EMG Data from Athletes

Collecting EMG readings does require some experience and expertise, but the demand of collecting data isn’t overwhelming. The biggest challenge isn’t the use of the software or other technology; it’s having the athlete follow directions, and also keeping the exercises consistent when performing a group analysis. EMG can be a perfect n=1 experiment, especially with biofeedback during return to play after an injury, but team or sports analysis is extremely difficult to do with complex motions because of styles and body types involved. The variability of EMG data can be misinterpreted as inconsistency or inaccuracy, but the true cause is likely the subjects rather than the measurement integrity.

Defining an event, or when a sporting action starts and stops, is difficult, and is a primary reason why video cameras or other tools synchronize with EMG. A continuous recording is hard to interpret, and a raw signal doesn’t fully explain what is happening in time and space. EMG is especially valuable for a time series or time course of events, rather than just being distilled to peak and average values of gross movements. Activity, the term used in EMG to summarize the nervous system providing a signal, is basically just a rise and fall of microvolts from the muscle. More electrodes placed at key muscles will create a wider, more-detailed picture of what is happening in the task being measured. This will, of course, require more analysis later. The comparison of relationships between limbs or muscle groups is extremely valuable to professionals in performance and therapy, and most of the superficial muscles are propulsive in nature.

Intramuscular EMG is usually performed for deep muscles or small muscles that simply can’t be read by electrodes. While intramuscular, or fine wire, EMG may sound painful, the wire is very thin and thread-like, making it surprisingly comfortable for most subjects being measured. Some athletes need to shave the testing area, such as muscle groups in the legs, and practitioners usually isometrically test the muscle group with a voluntary maximal effort or maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) to normalize the data.

Subject motivation will make a comparison limited, but there’s an expectation that using a contraction of near maximal effort will gain a perspective of the magnitude of activity. Each athlete will have to perform an isolated muscle contraction isometrically for each muscle recruited, thus making data collection take a little longer, but this is also common with other data sets from other sensors. Electrode placement is important as well, since some areas of the body are especially congested and can cause either crosstalk (false readings from other muscles) or misinterpretation from not knowing what muscle is being analyzed.

Common Errors in the Use of EMG in Research and Clinical Settings

Even researchers can make mistakes with EMG, since the instruments and environment can interfere with the collection of a pure signal. EMG is prone to motion artifacts when movements are fast and violent; thus, high-speed and high-force activities sometimes give false readings. Some resources have compiled a comprehensive list of the causes of errors, but most issues with collecting quality data are due to the limits of the technology and the way that subjects respond to instruction.

- Normalization, or creating a MVIC, is not a perfect process and subject errors are common.

- Electrodes can fail in different ways and require very precise placement. Additionally, not all muscle groups are ideal for EMG recording.

- Athletic motions or exercises are not always repeatable or easily captured, due to the subject’s reaction to having electrodes applied to their skin and body.

EMG recording, like any measurement, is only as good as the user and the equipment applied. Some bodies and some sports movements or exercises are easier to analyze because of very trivial but important factors, such as keeping the electrodes on the body in real-world settings. For example, sweat or ballistic actions will make electrodes fall off, even if elastic adhesive is used. Even an electrode staying on the skin when recording high-velocity movements is not necessarily a sign of a good reading, as skin will slide and not stay precisely on the muscle group like it does during slower activities. As stated earlier, manual isometric muscle contractions commonly create errors because new exercises are still foreign to athletes. Since experienced practitioners don’t always motivate the test subject enough or trust that the effort was maximal without objective measurement, a perfect MVIC baseline is hard to establish.

An athlete will naturally, and unknowingly, change their motion when they are aware that they’re being measured or tested. This is common with all measurements, as the simple placement of a camera during training may result in changes to technique or increases in effort. Some athletes are especially sensitive to having tactile sensors on their body, and respond negatively to the measurement because it’s distracting. No matter how accurate or precise an instrument is, the quality of the measurement relies on the quality of the action performed by the athlete. Having the athlete replicate in the lab what they do on the field is important to researchers, but in clinical settings and coaching environments, where the therapy room or field is actually the lab, repeated uses can’t disturb technique as practice time is sacred.

The quality of the EMG measurement relies on the quality of the action performed by the athlete. Share on XEven exercise events are difficult to measure, due to motion or technique variability that is large enough to taint the data. The nature of fatigue requires the need to average repeated bouts for a valid assessment. Measuring groups becomes especially difficult when the athletes have different levels of strength and size. In general, the more explosive and complicated the movement, the less accurate the EMG information will be, but the data is still useful enough to collect. Overall, the challenges of acquiring a set of clean EMG readings are not so insurmountable that it’s not worthwhile; it just means professionals using the measurements must be consistent and thorough.

How to Interpret EMG Signals and Draw Conclusions

After data is collected, interpretation and in-depth analysis are required to solve problems or summarize athletic events. EMG signals require filtering so the readings can be converted to actual values for comparison. Several filtering options exist, and most of them “clean up” the readings so a simpler representation can be viewed and charted. In addition to each individual recording, the group of recordings is often averaged or statistically analyzed as a whole with additional software. Due to the differences between each subject, the flaw with summarizing a group of recordings by a large population is that the variability can be misleading. On the other hand, not having the variability of a large population can bias or skew data because of small sample sizing.

Interpretation of the EMG recording is a combination of statistical and mechanical evaluation of what happened over time. Most practitioners break down the activity into sequences or partial actions in a timeline. Published research using EMG analysis has divided exercises into eccentric and concentric actions, like most strength exercises, but more complex athletic motions are done differently. In general, specific milestones in each sporting action, from start to finish, are dissected so comprehension is easier for both the reader and the scientist.

EMG is often paired with other instruments, such as force plates and video capture equipment, to create deeper analysis. Extreme analysis is possible, such as in-shoe pressure, motion capture, and physiological recordings. Longer capture periods can identify fatigue, due to the power output diminishing over the time course of the data collection. On average, more data sets help define both the context and meaning behind EMG.

There’s no perfect science to drawing conclusions with EMG, as it can be abused and misused because of the accessibility of the instrumentation. For example, just because an EMG reading is higher for an exercise doesn’t mean the muscle recruitment is truly better. Again, passive and active contractions are complicated events in muscle physiology, and higher average or peak values for a motion don’t indicate superiority. Conversely, EMG readings done properly are valid assessments of neuromuscular activity.

Muscle activation is higher or lower based on mechanical and conscious awareness of the recorded subject. A subject isometrically contracting a muscle group because they are guarding against injury or just conscious of the electrode can fool even an experienced practitioner of EMG, so expertise must go beyond just using the equipment and being in the field area tested. EMG data is not difficult to collect or analyze, it just requires a good advance plan to properly design an experiment and know what you want to eventually discover.

Popular Clinical and Training Facility Uses for EMG

The final piece of EMG science is its application in settings that are not research-based. Clinical and performance settings have more demanding needs in terms of time and efficiency, and EMG does add some preparation time before and additional analysis later. The overarching value of electromyography is its objective feedback, either instantly or gradually, for athletes. Generally, EMG is used in applied settings for these four reasons:

- To quantify a meaningful coordinative neuromuscular asymmetry beyond force production or speed.

- To benchmark changes in return-to-play training and follow-up in the years after completion of rehabilitation.

- To provide immediate biofeedback for athletes learning and mastering a skill or performing an exercise.

- To acquire new information on a specific sporting task to model better performance or more resilience to injury.

The common argument against EMG is not about its validity, but the practical need of getting a job done with little time. Most coaches and sports medicine therapists simply don’t have much time on their hands and athletes are somewhat apprehensive about getting data with electrodes, even if when placed on the surface of the skin. The amount of time needed before, during, and after EMG isn’t as large as it was in the past, due to advancements in wearable technology and better automation with software. In summary, a few extra minutes may save days and weeks if used judiciously, and best practice is not readily available in the clinical and applied performance arena today. With the rise of smart fabrics, the option of using EMG as a monitoring tool is promising.

Two main areas where EMG can influence sport are the development and the sometimes-necessary rehab of athletes. Training typically has higher demands in workflow because larger groups are involved, and rehabilitation usually has a better staff-to-athlete ratio. Both performance and medical practitioners need objective indications of change, and EMG is a more direct measure of muscle function than eyeballing alone. Combined with a talented and experienced professional, EMG adds more confidence to the true progress of the session, or can reveal regression if the athlete has a setback.

Without oversimplifying, medical professionals seek better balance to reduce injury occurrence or improve success after injury. Generally, performance staff wants to maintain ability or improve the development of athletic qualities. Both departments or fields have commonalities, but their responsibilities for injury diagnosis and training plans differentiate them. In modern sport, medical and performance roles are very hard to separate because training principles are applicable to both roles. The point where one role ends and the other begins is more ambiguous than ever.

Most EMG applications can be distilled if a muscle is underactive or overactive, or lacks specific timing with coordination. It can be easily argued that athletes will return with visual symmetry or coordination that seems efficient, but the muscle activity could reveal that more time is needed to be ready. As EMG proliferates in the clinical setting, better treatments and more effective training programs will evolve.

Deciding Whether EMG Is Appropriate for Your Environment

Electromyography is not for everyone, but nearly any level of sport can access the information without a major undertaking. EMG in research is far different than in a clinical setting, so if you are working with groups, most will find it difficult to apply. Several opportunities exist with EMG data, such as experimentation on athletic tasks and exercises, as well as return-to-play conditions. Nearly any team can make progress by adding EMG into their setting, but knowing the fundamental science behind it is a necessary starting point.

References and Suggested Research

- Dimitrova N.A. & Dimitrov G.V. Interpretation of EMG changes with fatigue: Facts, pitfalls, and fallacies. J Electromyography Kinesiology. 2003 Feb:13(1) 13-36.

- Farina, D., Negro, F., Gazzoni, M. & Enoka, R.M. Detecting the unique representation of motor unit action potentials in the surface electromyogram. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2008; 100(3), 1223-1233.

- Guissard N. & Hainaut, K. EMG and mechanical changes during sprint start at different front block obliquities. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1992; 24:1257-1263

- Maffiuletti N.A., Aagaard P., Blazevich A.J., Folland J., Tillin N. & Duchateau J. Rate of force development: Physiological and methodological considerations. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2016; 116:1091-1116.

- Massó N., Rey F., Romero D., Gual G. & Costa L. Surface electromyography applications in the sport. Apunts Med Esport. 2010; 45(165):121-130.

- Mero, A., & Komi, P.V. Electromyographic activity in sprinting at speeds ranging from sub‐maximal to supra‐maximal. Medicine and Science in Sports Exercise. 1987; 19(3): 266‐274.

- Reaz M.B.I., Hussain M.S. & Mohd-Yasin F. Techniques of EMG signal analysis: Detection, processing, classification and applications. Biological Procedures Online. Springer-Verlag; 2006; 8(1):163-3.

- Vigotsky A.D., Ogborn D. & Phillips S.M. Motor unit recruitment cannot be inferred from surface EMG amplitude and basic reporting standards must be adhered to. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2015 Dec 24.