Cody sits down with Brandon Reyes, current Assistant Strength Coach for Army West Point Football. Main topics include:

• The importance of tackling hard things

• How discipline and mindset are difference makers

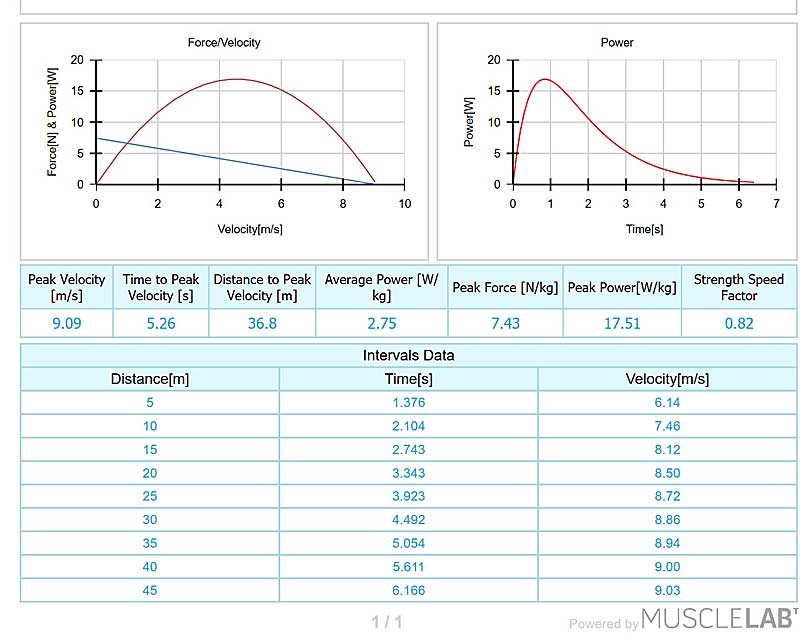

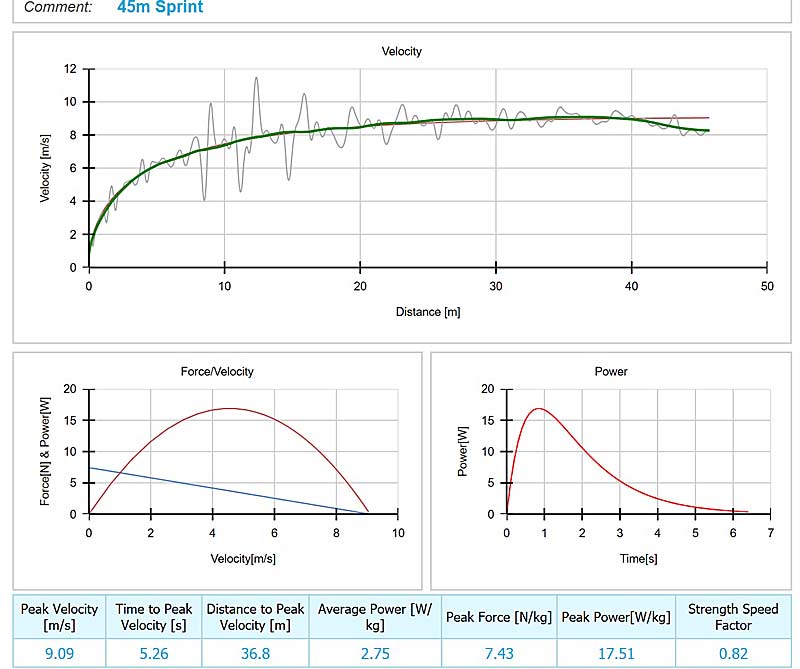

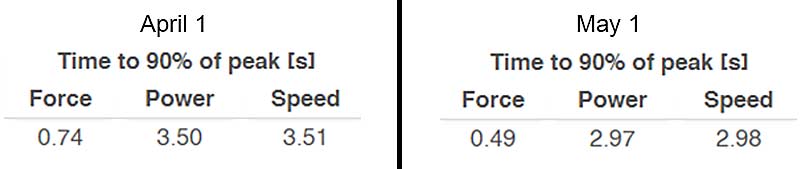

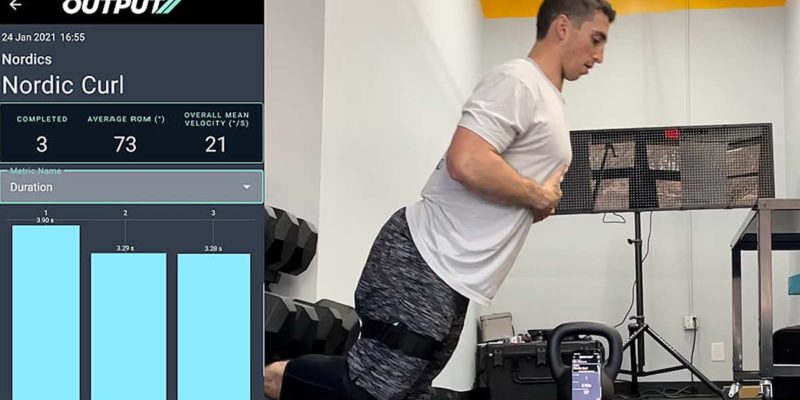

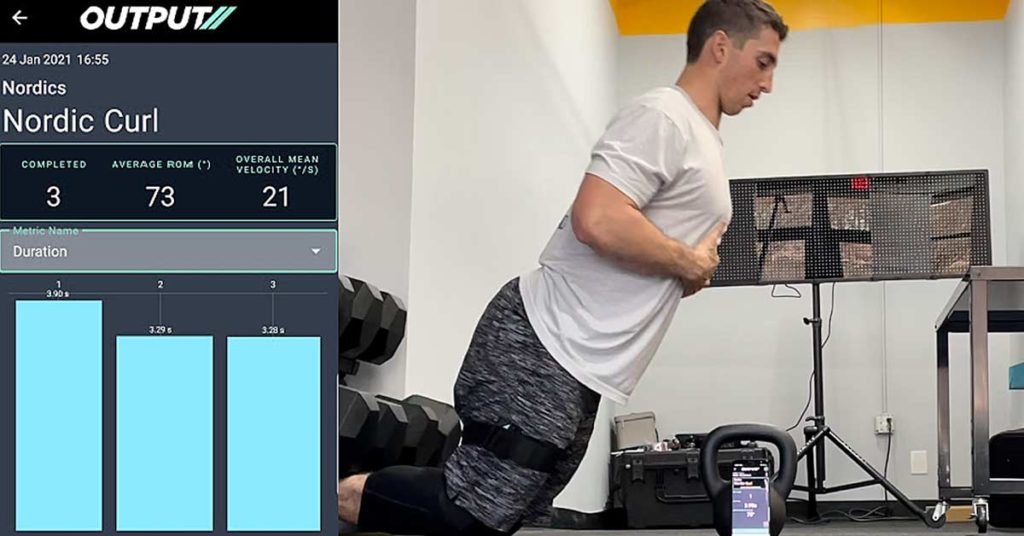

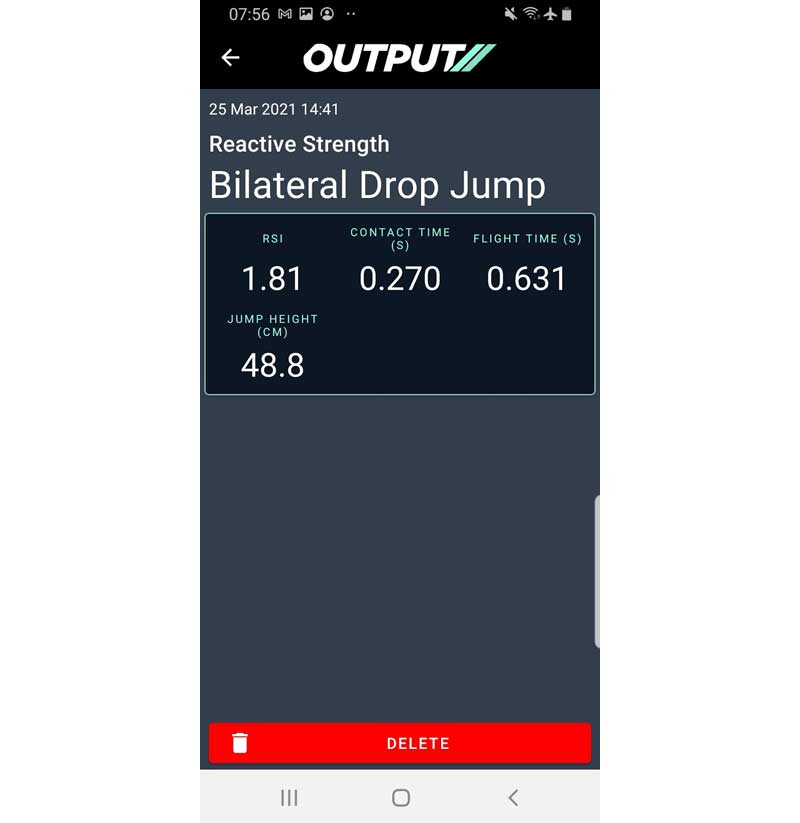

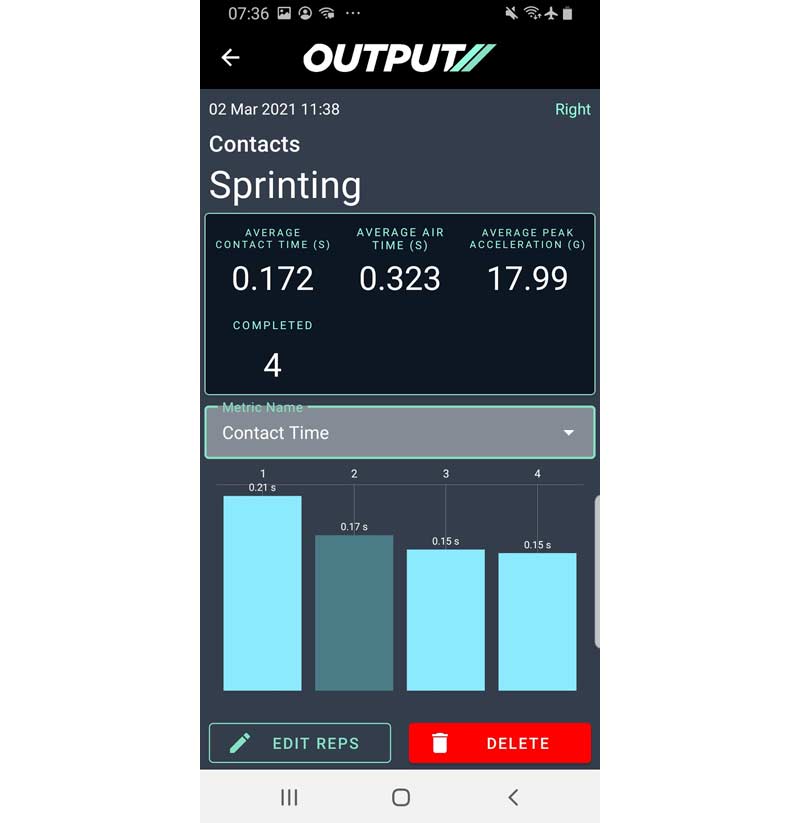

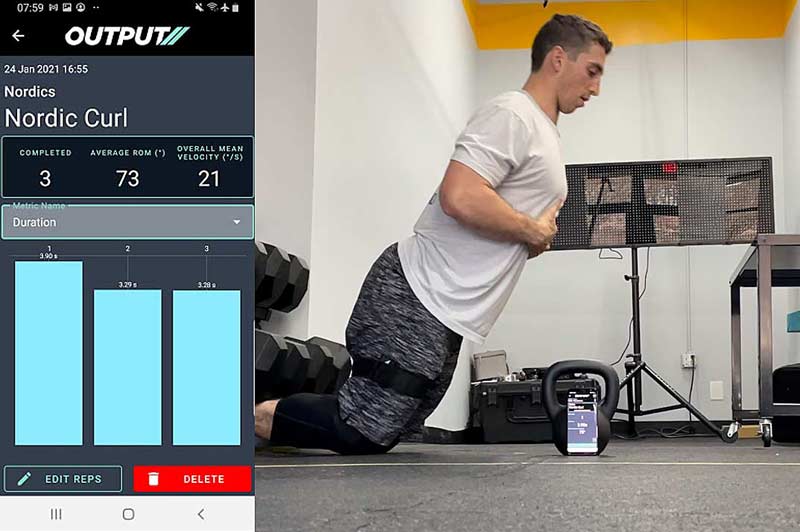

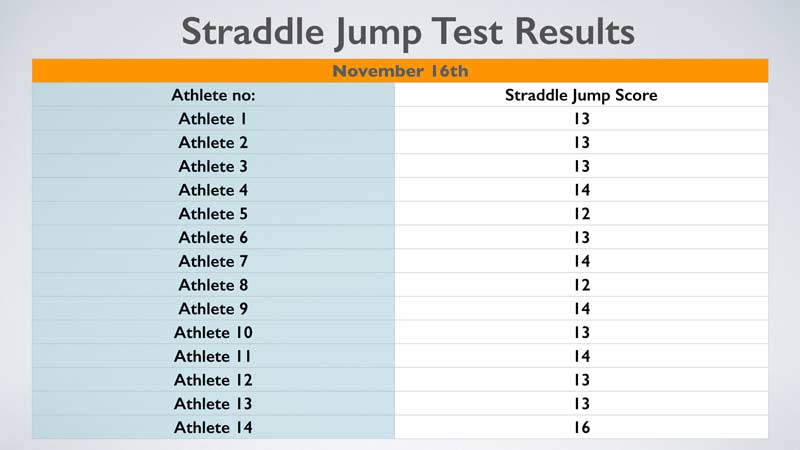

• Sports Science measurements and data collecting

Cody and Brandon also break down the clean and make a case for why it can be a useful tool when training athletes

Connect with Cody and Brandon:

Cody’s Media:

Twitter: @clh_strength

IG: @clh_strength

Email: [email protected]

Brandon’s Media:

IG: @coachbrandonreyes

Twitter: @CoachBReyes