In order to train more explosive athletes, the approach that our staff at Total Motion Performance has found the most beneficial is an integrated program with weights, med balls, sprints, and plyometrics. Properly dialing in your plyometrics routine has a number of benefits. First, plyometrics are often a high-intensity exercise, and when executing these types of movements, it is critical that you have a proper progression in place. When performing exercises that tax the central nervous system, you only can perform a limited volume of work.

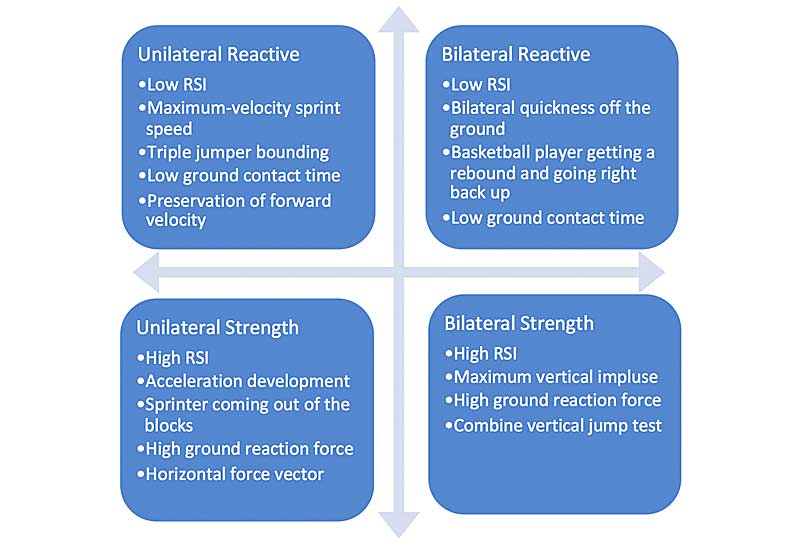

Knowing this, when training with plyometrics, coaches need to prescribe the correct exercises in the correct doses. Without the correct prescription and dose, in the best case the athletes will just fail to get better; in the worst case, they end up hurt. In this article, you will find a simple way to assess your athletes and deliver the plyometrics routine that will benefit them the most. I break down the movements into both unilateral and bilateral and also categorize them based on the reactive strength index (RSI) of an athlete.

Reactive Strength Index (RSI)

In a lab setting, RSI is calculated by dividing jump height by ground contact time. This gives the sports scientist or researcher insight into how well an athlete produces force. Athletes who produce force faster, with higher jump heights and lower contact times, show they are better at utilizing their stretch-shortening cycle (SSC). From the standpoint of training for performance, it is important for coaches to simply get an RSI to determine if an athlete needs to work on their stretch-shortening cycle or their concentric strength (CS).

Our staff has determined a different calculation for RSI and how it can be useful in programming plyometrics, says @kingashton1. Share on XKnowing this about RSI, our staff has determined a different calculation for RSI and how it can be useful in programming plyometrics. The way we measure RSI is:

- First, we have the athlete do a countermovement jump (CMJ) using a Just Jump pad.

- Then, we have the same athlete perform a static vertical jump (SVJ). To get an SVJ, we have the athlete go down and pause at the bottom of their jump for three seconds before exploding upward. (To truly measure an SVJ with no countermovement, you would need force places. While our Just Jump pad is not 100% accurate, it is a good start in being able to better classify athletes.)

When measuring RSI, if an athlete tests well in the CMJ but not as well in the static vertical, this indicates that the athlete is utilizing their SSC well but is not utilizing their CS as effectively. Conversely, an athlete who has similar results on their CMJ and static vertical is not utilizing their SSC very well but is using their CS effectively.

Anecdotally, in the gym we often see that athletes who use their SSC well have less knee flexion in the CMJ. Athletes who aren’t utilizing their SSC well go into more knee flexion when performing their CMJ. Research shows that as knee flexion in the squat increases, muscle recruitment increases. Knowing this, athletes who are not utilizing their SSC as effectively may be aiming to recruit more muscle fibers by going into a deeper squat to make up for their lack of SSC involvement.

The main takeaway here is that whether an athlete utilizes their stretch-shortening cycle well or not, there are different types of training that you can give each respective athlete to maximize their potential.

Bilateral vs. Unilateral

Bilateral plyometrics focus on using two feet to produce force, while unilateral plyometrics use one foot. Traditionally, athletes can produce more force bilaterally than unilaterally. Knowing an athlete’s goals is very important for a coach when writing a plyometrics program.

When writing a plyometric program for an athlete who is aiming to improve their 40-yard dash, bilateral plyometrics would make the most sense for someone who struggles with their acceleration (the first half of the run). Knowing that acceleration is all about overcoming inertia, programming bilateral plyometrics makes more sense given they have the ability to create higher ground reaction force.

For an athlete needing max velocity work, however, it would make sense to program unilateral plyometrics such as bounding rather than box jumps. At max velocity, sprinting is about creating quality ground contacts to enhance flight time and preserve linear velocity. Bounds are a better way to train this, as opposed to a bilateral plyometric.

A coach must be aware of an athlete’s needs and do their best to enhance those needs through training—and a dialed-in plyometrics program will do that, says @kingashton1. Share on XSprinting is just one example of how a tailored plyometric routine could help benefit athletes more. Dr. Matt Rhea does a great job breaking down how to improve different segments of the run, if you want to dive more into that topic. Some further examples could be volleyball back row versus front row, basketball players going off one foot or two, and so many others. A coach must be aware of an athlete’s needs and do their best to enhance those needs through training—and a dialed-in plyometrics program will do that.

Bilateral Reactive Focus

Athletes falling into this category would have a low RSI, meaning they need to work on their SSC abilities. In this category, the goal is to improve ground contacts and vertical impulse. We do this by starting with extensive plyometric exercises that focus on creating a more robust SSC and then progressing them to more intensive exercises. A progression could look similar to the following.

With the progression outlined above, athletes are able to create a robust foot-ankle complex before moving on to more intensive plyometrics that place more and more stress on the body. Rudiment hops start by teaching an athlete how to strike and interact with the ground, and the box drop is a progression of this. Depth/drop jumps then prepare the athlete to take the added force of falling from a box and turn it into usable energy on the following jump. Finally, the continuous hurdle hops challenge the athlete to not only get up high, but to also be quick off the ground in between hurdles.

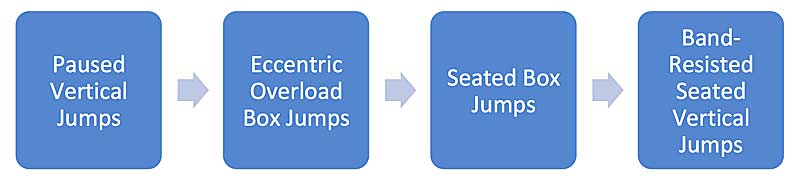

Bilateral Strength Focus

When looking at an athlete who needs bilateral strength-based plyometrics, this athlete would test high in RSI—meaning they use their SSC well but lack concentric strength. The goal of this category is to create higher GRF to improve the ability to overcome inertia and accelerate more efficiently. First and foremost, athletes who are in this category often need foundational strength work (which is a topic for a different day). But for an athlete in this category, a sample plyometric progression could look like this:

Using a progression like the one above gives an athlete who needs more concentric strength the ability to do so without regressing their already good reactive abilities.

- With the paused vertical jump, athletes have to pause at the bottom; however, there will still be a slight countermove, which is why it is the first exercise in the progression.

- Next, the eccentric overload box jump forces an athlete to be slower during the eccentric phase of the countermove and go into more knee flexion.

- Seated box jumps take the countermovement away and force the athlete to rely on their concentric strength.

- Finally, the resisted vertical jumps take the countermovement away and overload the movement, forcing the athlete to really work hard to create a high take-off velocity.

The importance here is not to turn the overloaded movements into strength exercises—the dumbbells should be light on the overloaded box jumps and the bands should be light on the resisted vertical jumps.

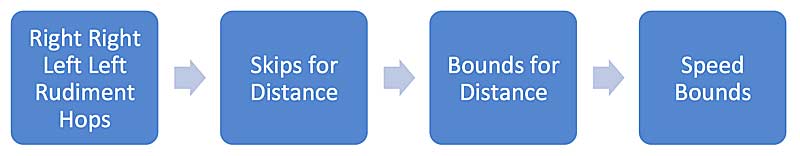

Unilateral Reactive Focus

The reactive horizonal group is for those athletes who have a low RSI. To get the most out of their plyometrics program, these athletes first need to learn how to interact with the ground correctly, and then to create force rapidly upon ground contact. A sample plyometrics progression that we would give an athlete who falls into this category is as follows.

The RRLL hops start to teach an athlete how to prepare for ground contact and work on building a quality foot, ankle, and lower leg complex. Skips for distance teach an athlete to produce force while maintaining forward momentum. Bounds for distance do the same, but it is often more challenging for an athlete to bound rather than skip—hence, the skips before the bounds. Finally, the speed bound focuses on creating maximal forward velocity, while still emphasizing a good flight time by producing high GRF.

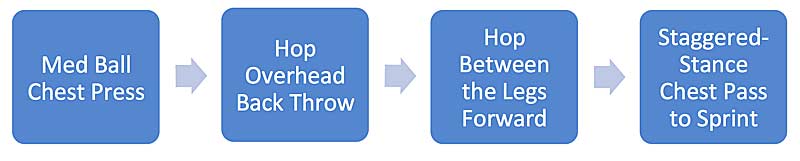

Unilateral Strength Focus

Athletes falling in this category will test high in the RSI, meaning they are reactive athletes. The goal of this category is to teach an athlete to create more GRF. Utilizing med ball throws in conjunction with plyometrics, hops, and jumps is another way to overload the movement and force an athlete to create more GRF.

The push press starts the progression by teaching the athlete how to create basic GRF using both legs, which is vital in acceleration. Next, the hop overhead back throw adds a larger triphasic component, giving the athlete the chance to create even more GRF. After that, the “between the legs forward” allows the athlete to still work on the goal from the first two exercises but starts to let the athlete feel what is like to create a horizontal vector of force rather than purely vertical. Finally, the staggered-stance chest pass to sprint puts the athlete in a start position with the staggered stance and starts an athlete from a dynamic position on the sprint rather than a standstill.

Use for Better Insight

This rest/retest method can give coaches better insight into the weaknesses of an athlete and how to prescribe a plyometric program to improve their in-game performance, says @kingashton1. Share on XPlyometrics are a great supplement to a well-thought-out training program. However, to get the most out of a plyometrics program, a coach much progress the exercises in the right manner to reduce injury risk and maximize adaptation. Coaches should first create a sound plyometric base in their athletes before aiming to implement more advanced plyometric progressions. Once the base is created, using this test/retest method can give coaches better insight into the weaknesses of an athlete and how to prescribe a plyometric program to improve their in-game performance.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF