We are currently in the midst of the biggest, global world-changing event in most of our lifetimes. When all of this (hopefully!) blows over, we are going to be living in a very different world. What worked pre-coronavirus might not work in the world we inhabit afterward. Lockdowns and shelter-in-place orders have provided us all with a chance to think about what matters and assess how we operate—it will be interesting to see how much changes within the world of coaching and strength and conditioning as we move forward. With a period of reflection, there are likely to be changes made in how we operate, either from things learnt or simply out of necessity.

With that in mind, one of the most comparable periods for what we are currently living through is the off-season. With a sustained period of time away from our athletes—as well as varying training environments and minimal contact time—there are many similarities between lockdown and the offseason. The off-season varies widely between sports, but is a yearly problem that every coach has to solve. So, with athletes worldwide being put into an enforced lockdown:

- What can we learn as a community of coaches from our experiences?

- What innovations can we apply to future off-seasons?

- How do we continue to impact our athletes when they aren’t seeing us day in and day out?

- Should we do anything different the next time our athletes have an extended time off?

Depending on the sport and level of athlete you work with, the offseason period can differ greatly: spanning as little as 2 to 3 weeks for professional footballers to sports like the NBA and NHL, which can have as long as 4 months off between formalized training! Similarly, with the lockdown orders, there was a large variation in circumstances based on geography.

In the UK, we were allowed outside to exercise once a day but gyms were closed; in countries like South Africa, they had allotted outdoor exercise windows that lasted only a couple of hours. In countries like France, some people were confined to their homes completely, leading one brave/crazy man to run a marathon on his balcony!

Return to Play

We need to understand these constraints before we even begin to formulate a new training plan. This is the same as in the off-season, where each athlete’s situation will dictate how we may support the player and what we may (or may not) expect from them. For example, if a player has been involved in a grueling season and they only have two weeks of downtime, I’m pretty sure the last person they want to hear from is you!

Also, from a physiological perspective, you will only get very small decay of physical capacities in that short time—so you can afford to be more relaxed with what that player does or doesn’t do. Conversely, those with a large period of time off would need more support, and to be more closely monitored, because the opportunity for the player’s physical qualities to decay is high. This can lead to a higher risk of injury upon the return of training. Just look at the number of Achilles tendon ruptures in the NFL after the enforced lockout in 2011, and you can see what happens when athletes can’t (or won’t) put in the work.1

Injury risk is probably the first and most important issue to address, and we have already seen in the Bundesliga’s return from lockdown that injuries are higher than normal. This isn’t just a football problem either: one team in Rugby League suffered two non-contact ACL injuries in the first 20 minutes of the same game when returning to action.

Performance degradation is another key element to try and address in an athlete’s off-season training. Some markers of performance will inevitably decline, but the goal of off-season training is to attenuate this as much as possible. Being in charge of an athlete’s physical condition can potentially be frustrating when you have to rely on them to remain self-reliant due to a lack of contact time.

This is a key learning point of the lockdowns: there will be times where we can’t be there to help our athletes, so we need to empower them to be more self-sufficient, says @peteburridge Share on XThis is a key learning point of the lockdowns: there will be times where we can’t be there to help our athletes, so we need to empower them to be more self-sufficient. This is where educating them and involving them in training decision-making is important, providing a deeper understanding of the training process. At times we can do too much for our athletes and they become over-reliant on us. The goal for most coaches/S&C’s is to make the player less and less dependent on you. This doesn’t sound like a good business model, but we should go from the person forging the path for our athletes to the person simply providing the guide ropes, so that our athletes can then forge their own.

Maintaining Essential Physical Qualities

The lockdowns also provided an opportunity to challenge the misconception that our athletes need to be in a gym with us to perform good-quality physical training. Very few athletes will have had access to top-flight gym equipment, so we’ve had to adapt. This is exactly like the situation we face in the off-season, so the innovations we have made in this period can be very readily applied in the future.

Many coaches have been highly creative in this period, making the best out of the hand they have been dealt. Canadian inventor Ann Makosinski has said that “creativity is born out of necessity,” and this version of the proverb couldn’t be more apt for this period. I hope that some of those innovations carry over to future training, whether that be in the novel ways we have interacted and checked-in with players, or the creative ways we have found to load our athletes to get worthwhile training adaptations without lots of equipment.

Video 1. Athletes have used sandbags, breeze blocks, backpacks filled with tins of beans, and other household items to better load movements. Even cartons of milk can be reused to load a movement!

When we look at training on a continuum—from doing nothing at one end to full training at the other—it becomes easier to pitch someone’s training. If someone spent the lockdown doing absolutely nothing, their physical capacities will have dropped off about 2-4% per week.2 If an athlete spends a long off-season like this, it will likely leave them as an unwelcome statistic on an injury monitoring blog! However, we need to be aware that training isn’t an all or nothing event—once you’ve already got it, you don’t need to do a lot in order to at least cling to what you have.

Training just 20% of what you would normally do cuts losses in aerobic capacity in half. 3 Younger athletes need far less training than you’d expect in order to maintain certain physical qualities—around 1/6th of the training input, compared to 1/3rd for older athletes for strength and hypertrophy.4 Knowing this, coaches can sleep a little easier at night! Moreover, with players who tend to worry a lot during time off from training, educating them on these things can help performance anxiety that might be brought about by not training at their usual levels.

Having this minimum effective dose approach can help free up a lot more time for an athlete in their off-season to focus on things away from the sport and training. One of the challenges of lockdown, though, has been making sure we do provide an effective dose, utilizing exercises that are going to be potent enough to cause physiological adaptations. Unfortunately, random 5k runs mixed in with burpees and sets of bodyweight squats to infinity aren’t the most targeted of training prescriptions!

This is where, as coaches, we’ve had to innovate to find new exercises and also to embrace technology to make remote programming more bespoke to our athletes.

Video 2. Without a great deal of external load, it is important to think creatively to find ways to overload. Manually resisted eccentrics are an easy way to achieve an overload—as long as you can convince someone to spot you!

Individualizing Training for a Full Squad

Most off-season programs tend to be a blanket program carefully curated on Excel. They are then ‘sent to all’ in the hope that at least some players do more than just chuck it into the boot of their cars to collect dust. Unfortunately, no matter how fancy the formatting, a generic program is unlikely to meet an athlete’s individual needs. Furthermore, unless there is some form of accountability with the athlete, the coach has likely wasted a lot of their time.

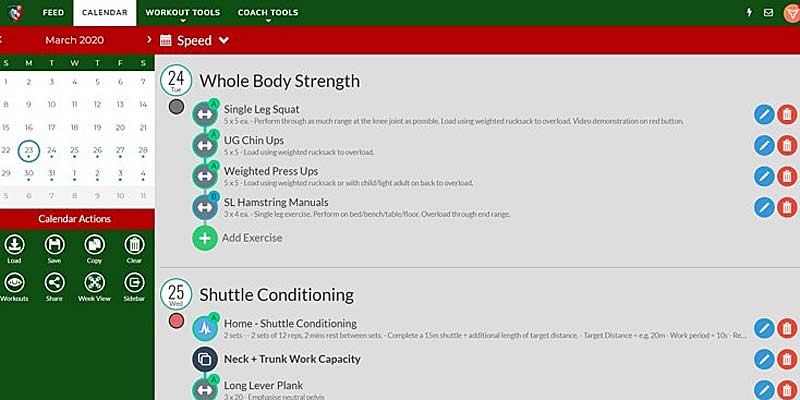

This is where athlete management systems like TeamBuildr and CoachMePlus have come into their own in the lockdown period. The software not only allows quick, simple, and adaptable programming, but also provides athlete accountability and continued engagement. On a daily basis, coaches can check in and interact with athletes, no matter where they are in the world. This technology is—at the very least—attractive for off-season periods, and some coaches may continue to use them in-season as well.

Coaches may be new to the use of apps like Smartabase, TeamBuildr and CoachMePlus, and perhaps like me are still biased towards Excel. But in a situation like the off-season, athlete management systems are great tools that are simple for the end user and can help get bespoke programs out quickly and effectively. Also, the customization of exercises and an exercise library are useful if you want an athlete to perform an exercise in a particular way, or if they are constrained by equipment. For example, one athlete I coach didn’t have access anywhere to do chin ups, but had a TRX attachment and a big tree in his back garden. TRX Tree Chin-Ups were born, and with it came a video demo of what to do and coaching cues of how to perform the exercise.

Monitoring Data and Meeting Apps

Other technological innovations that have been particularly useful during the lockdowns are data trackers and wearables. These are also hugely applicable for use in a typical off-season, bridging the gap between what a player gets at the training ground and what they might be able to track at home or on the road.

Many teams will use GPS and HR systems to track numerous metrics and monitor load. These units are expensive and require smart minds to collect, collate, and analyze the data; however, GPS apps like Strava and HR monitors in Apple watches and FitBits can provide rudimentary data on sessions. These are becoming increasingly user-friendly to upload and analyze—the accuracy isn’t what the big companies like Catapult and Polar may provide, but can help training prescription and put more accountability on the player. For example, the stories of footballers putting a GPS unit on their dog to pick up running load may be hard to prove, but it is much harder to fake the HR trace that a tough running session will provide.

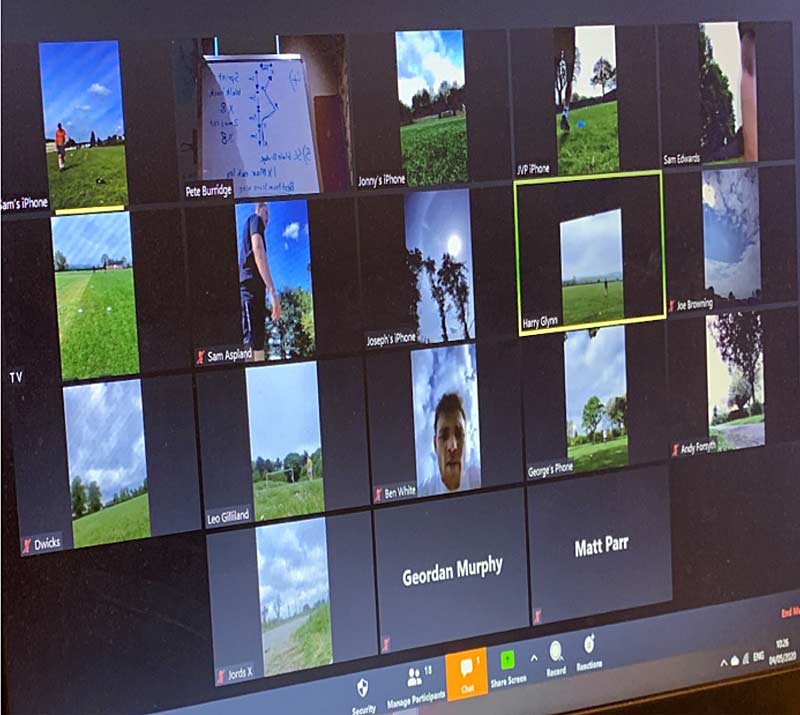

Finally, another method I’m sure most coaches will have experienced is group sessions on Zoom (have you even lived through lockdown if you haven’t been on a Zoom call?!). These can be hard to coordinate and will forever be plagued by the one person who doesn’t mute their mic, but are still a very useful tool to keep a playing group together. The online meetings maintain team cohesion whilst simultaneously giving you an opportunity to get a session in with the playing group.

Don’t get me wrong, session design with varied equipment provision and a 35 man waiting room can be quite hard…but with some creativity, it can be pulled off. During the lockdown, many athletes I coach said they missed the feeling of being ‘with the lads’ in training, and often found it hard to motivate and push themselves when working out alone. Similarly, this is a problem many athletes face in the offseason and Zoom can be a great tool to solve it.

During the lockdown, many athletes I coach said they missed the feeling of being *with the lads* in training, and often found it hard to motivate and push themselves when working out alone, says @peteburridge. Share on XDuring lockdown, we regularly held large-group fitness sessions so that the players could have the type of ‘shared hardship’ that would—albeit artificially—bring the guys together. We also used Zoom for 1-on-1 sessions with rehabbing players or players who needed a little more direct attention.

With a small group of our players, we even managed to run group agility/COD sessions, where the lads competed in teams against each other in relays. This was perhaps the hardest thing I’ve ever had to officiate, with players running off screen and back again as I was trying to watch for the inevitable ‘bending’ of the rules: scanning 16 tiles on my screen for who finished first at times had me like the monkey from Toy Story 3! But despite these difficulties, it was achievable and allowed me to get a squad-wide sprint and deceleration stimulus in a competitive environment—remotely—whilst the players had fun at the same time.

Using Constraints to Re-Think Training

Many coaches will have had new experiences of how we deliver, but the key learnings from lockdown have been based around what we deliver under the constraints we faced. It has been great to get our athletes back to some sort of ‘normal’ training at our facility, but come the off-season, we will face the same problems again. To steal from survival expert Bear Grylls (American readers may know him better from the internet meme), we have to improvise, adapt, and overcome. This improvisation has helped open up the toolbox to include something more than endless press-up challenges!

Achieving an effective and potent stimulus is a key outcome in the off-season, especially as we have a smaller training budget to spend. Thinking about why we do something can assist training decisions. Most programs will look to maintain strength in the off-season, but unfortunately peak force is hard to develop with just bodyweight exercises and minimal equipment, especially for stronger athletes like rugby players. This is an important quality that underpins a range of athletic actions, but degrades in about 14 days without a good enough stimulus.5 With some creativity, however, peak force can be achieved. Things like pushing cars, deadlifting boats, and squatting people are all potential options at the fringes of creativity.

Video 3. With creativity, overload can be found in many places—just be careful about members of the public mistaking your intentions when you do these workouts in the neighborhood!

Sometimes, simpler strategies like going to muscular failure can sufficiently maintain strength—at the very least, this certainly provides a potent hypertrophy stimulus.6 For stronger individuals, however, it does mean doing a large number of reps, which can be very arduous to achieve. Other strategies include maximal isometrics, which without equipment can be performed with the help of an old towel in different positions. Performed with maximal intent, these on their own can maintain peak force, and maybe even increase levels of peak force in more untrained individuals.7

With careful ordering of exercises, performing sets to failure preceded by maximal isometrics can make the set of max reps much, much harder, so you don’t have to go to silly amounts of reps to achieve muscular failure. Share on XWith careful ordering of exercises, performing sets to failure preceded by maximal isometrics can make the set of max reps much, much harder, so you don’t have to go to silly amounts of reps to achieve muscular failure. Finally, an obvious and easy-to-execute strategy is training single leg movements. Exercises like single-leg squats, skater squats, and loaded lunges can all serve you well (the first two in particular don’t need much load to provide a potent stimulus). The only issue is there is a higher coordinative demand to perform these, but for someone facing an off-season period of perhaps 4-6 weeks, large improvements can be made in movement proficiency if they don’t already appear in your in-season programming.

Video 4. There are multiple ways to try to achieve adaptations in peak force in the lower body when limited for equipment—here are a few that are worth trying with your athletes.

Another strategy that is useful if an athlete has access to a willing participant is the use of eccentric overloaded exercises. Not a lot (if any) plate weight is needed, you just need someone to provide a bit of resistance for exercises like chin-ups and press-ups. Eccentrics are fantastic for developing peak force. It is easily something an athlete can do with a housemate at home, or with their wife or significant other on the beach on holiday. Eccentrics are perhaps easier to perform with upper-body exercises, but with some experimentation, single-leg squats and rear-foot-elevated split squats can be overloaded this way too. Due to eccentrics being a potent stimulus, large volumes aren’t needed either, which allows more time to be spent away from training—making it a particularly appealing strategy for off-season maintenance.

Video 5. Many exercises can be performed with minimal to no equipment if you get creative.

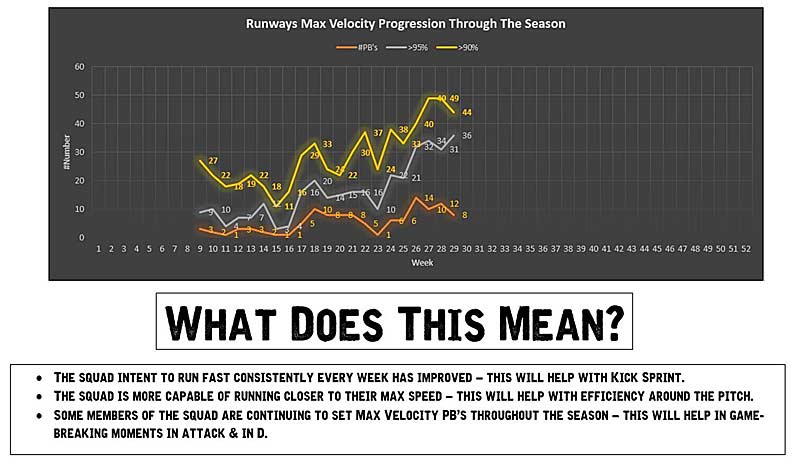

Don’t Neglect Speed

Finally, an argument could be made that keeping up a consistent thread of sprinting is probably the most important stimulus team sport athletes should be doing in the off-season. Additionally, sprinting has been shown to help maintain/improve fascicle length, which is important to protect against hamstring injuries.8 This really isn’t (and shouldn’t be) counted as an innovation, but there are some out there who are just now starting to realize the potency of a regular sprint stimulus to help with performance and injury prevention.

Looking from the perspective of hamstring injury prevention, if players aren’t getting the sprint stimulus, they absolutely have to keep up some strength work in the hamstrings. This can be achieved isometrically, with exercises like long lever bridges and planks; or, eccentrically (with a bit of creativity), either manually resisted or doing exercises like Nordics off of whatever you can find!

Video 6. If you’re on your own but need to stay on top of your hamstring strength, hooking your feet under a car can allow you to do Nordics very easily.

Looking Ahead to Your Next Off-Season Break

So, what can we learn from being locked down for so long? What can we change? How can we evolve our practice? We will each take our own learnings and reflections from this period, which can then be applied to our practice. One of my key takeaways from lockdown, which I intend to apply in future off-seasons, is getting more comfortable not having total control of a player’s program. Empowering my athletes more and placing a greater focus on education should help them foster a deeper understanding of their program.

Secondly, we have to make sure we know the why of our training, so that we are achieving physical adaptations. There is a difference between exercise and training, and our job is to provide targeted training that is relevant to an athlete’s physical development rather than just doing Instagram exercises that equate to nothing more than entertrainment.

A greater understanding of the effects of detraining can also better frame our training and alleviate our fears of a player regressing too much. The volumes needed to maintain numerous physical qualities are perhaps a lot lower than we’d expect. Knowledge of this takes the pressure off and we can perhaps allow our athletes a bit more of a mental break to enjoy time away from training—as long as they do perform the minimal effective doses that we prescribe.

From there, we can prioritize certain things that need to be worked on which are actually achievable on the road, at the beach, or at home. Many coaches have shown a great deal of creativity during this period (a lot of what I’ve shared has been shamelessly stolen or adapted from other coaches’ ideas!) and this needs to continue when we are planning for off-season training. If we can continue to find novel solutions to these problems, we will be better set up for success. Whether that’s using things like maximal isometrics, creating load out of household items, or putting your partner on your shoulders and squatting them!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Cherny CE, Heidt RS, Hewett TE. “Did the NFL lockout expose the Achilles heel of competitive sports?” J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41(10):702-705.

2. Maldonado-Martin, Sara & Cámara, Jesús & James, David & Fernádez-López, Juan & Artetxe-Gezuraga, Xabier. (2016). “Effects of long-term training cessation in young top-level road cyclists,” Journal of Sports Sciences. 35.

3. García-Pallarés J, Sánchez-Medina L, Pérez CE, Izquierdo-Gabarren M, Izquierdo M. “Physiological effects of tapering and detraining in world-class kayakers,” Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(6):1209-1214.

4. Bickel, CS, Cross, JM, and Bamman, MM. “Exercise dosing to retain resistance training adaptations in young and older adults,” Med Sci Sports Exerc 43: 1177–1187, 2011.

5. Hwang, Paul S; Andre, Thomas L.; McKinley-Barnard, Sarah K.; Morales Marroquín, Flor E.; Gann, Joshua J.; Song, Joon J.; Willoughby, Darryn S. “Resistance Training–Induced Elevations in Muscular Strength in Trained Men Are Maintained After 2 Weeks of Detraining and Not Differentially Affected by Whey Protein Supplementation,” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research: April 2017 – Volume 31 – Issue 4 – p 869-881.

6. Schoenfeld, Brad J. “The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training,” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research24.10 (2010): 2857-2872.

7. Oranchuk, Dustin & Storey, Adam & Nelson, Andre & Cronin, John. (2019). “Isometric training and long-term adaptations: Effects of muscle length, intensity, and intent: A systematic review,” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 29. 484-503.

8. Mendiguchia, Jurdan, et al. “Sprint versus isolated eccentric training: Comparative effects on hamstring architecture and performance in soccer players,” Plos one 15.2 (2020).