Heart rate and lactate responses, along with subjective indicators, have been the go-to solution for internal load response for years. It’s time to move on. We need to fully integrate the internal load using sports thermography and other indicators of muscle response, as the neuromuscular system is just as important as the cardiovascular system.

Over the course of this article, I propose a major paradigm shift in sports monitoring: measure muscles directly with noninvasive means. Along with the new direction, I promise additional methodologies that fully support existing techniques in tracking the training response, including the latest concepts in sports monitoring.

External and Internal Load – Bridging the Connection

I was interviewed on thermography in sport some time ago on SimpliFaster and contributed an article explaining how ThermoHuman can help professionals monitor their athletes. In this article, I take a step back to explain the monitoring process in more detail, as it’s difficult to make progress if foundational information is not fully comprehended.

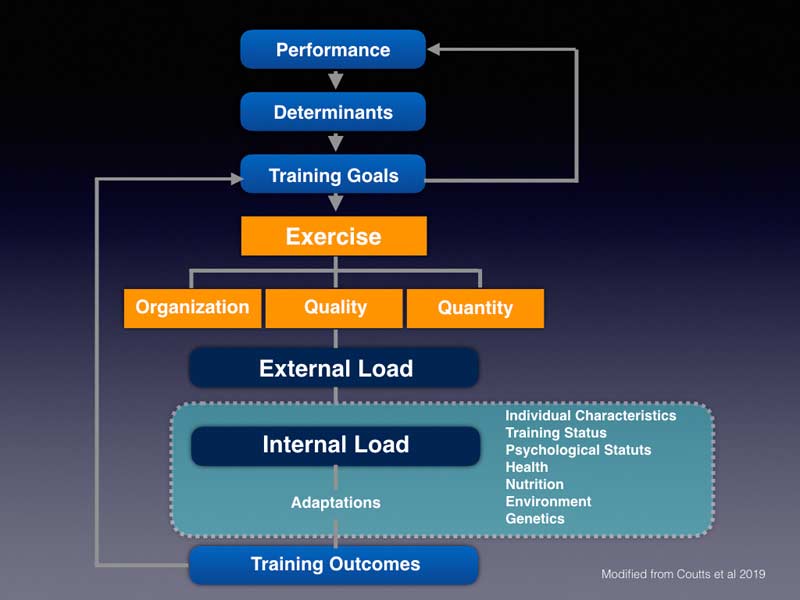

Sports thermography can summarize internal load, a product of the work performed and the current condition of the body. Using thermography to immediately evaluate residual training for readiness or post training for decision-making is both effective and efficient. The process is effective because it objectively identifies how muscle and other soft tissues are responding to training, and the speed and automation of software is fast and reliable. In my own monitoring program, it’s the focal point between both internal and external load monitoring.

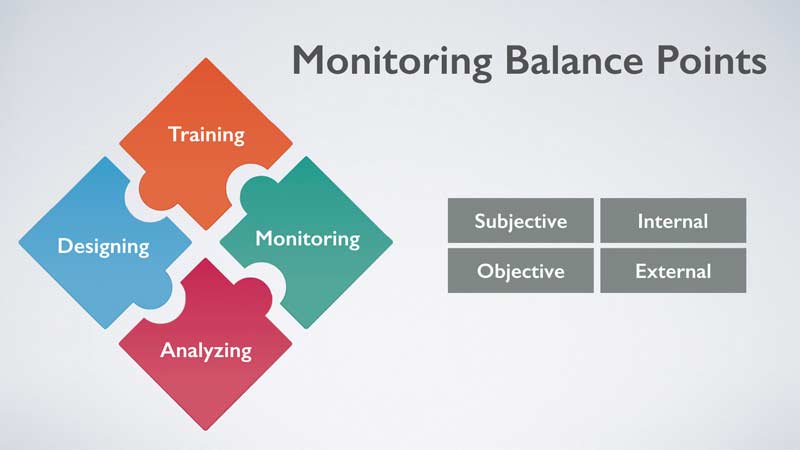

The quadrant of subjective, objective, internal, and external load monitoring is often cited as a way to convey relations between types of data with monitoring in sport. Today, many of the metrics to monitor workload have had backlash in the scientific community, including the acute chronic work ratio. Furthermore, coaches have experienced a poor cultural response from monitoring, as too much measurement seemed to have caused either poor compliance or low morale.

The solution is multifactorial and will require support staff to find alternative ways to protect athlete health while improving injury rates for at-risk populations like elite athletes. Instead of using a conventional model for monitoring, we need a fully integrated method of bridging both the perceptual experiences and the load response to training and competing.

The use of thermography weaves the athlete response, both internally and subjectively, into an objective summary that is quick and easy. Immediate decisions and adjustments can be anticipated and refined to monitor the superficial temperature, and all departments can use the information collected. Fitness coaches can adjust exercise regimens, physiotherapists can increase services and restorative modalities, and sport scientists can use their existing processes to oversee the workload of the players.

Without question, sport thermography is a perfect tool for teams that need specific information on actual muscles rapidly. If employed as a part of the internal load response with athletes, thermography connects all perspectives by tying all of the data to common areas of injury and fatigue. Impellizzeri, Coutts, and Macora proposed a model for implementation and education with internal and external loading.1

Biochemistry and Biomechanics

A common discussion point for medical and performance staff is the desire to address the links of muscle injuries and genetics, along with mechanical and biochemical load. Risk factors such as muscle strength, poor sleep, and nutritional insufficiency can turn standard athlete monitoring into a demanding process that is both exhausting and difficult to implement rapidly. Therefore, using conventional approaches and complementing them with thermography makes sense, namely because most of the actions after assessment include passive recovery methods and local strength and conditioning. Recent peer-reviewed research on athlete asymmetries in professional football indicates potential performance loss and possible connection to past injuries. Continual struggles with risk past healing times is evident with those who tore their anterior cruciate ligament in the past and reinjured the same or contralateral leg.

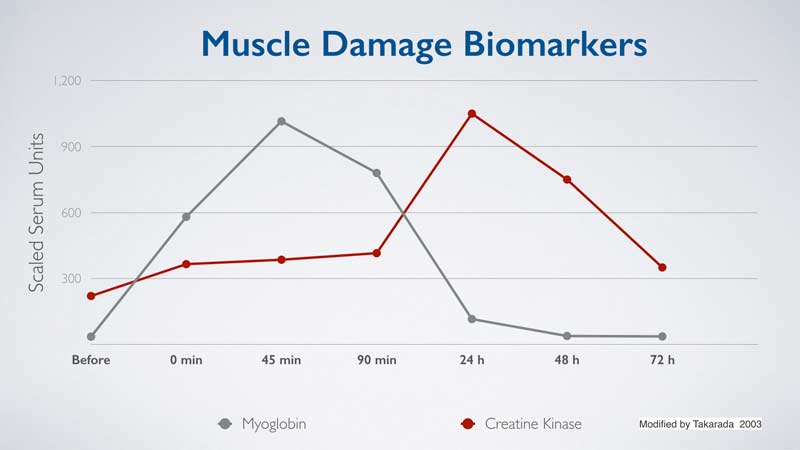

Teams investing in wireless surface electromyography should consider thermography, as the entire body can be scanned quickly, improving the odds of successful screening. In conjunction with manual testing using dynamometers or other devices, medical staff is more than welcome to use sonography as a way to confirm low-grade tears and pulls. Supporting data on delayed onset muscle soreness and injury diagnosis reveal that thermography and biomarkers (creatine kinase) are potentially useful to see the severity of muscular overload. Established studies are cautiously optimistic that it’s enough evidence to include in a comprehensive monitoring program. If a club or team wishes to conduct both biochemical testing and thermography, we recommend following the same procedures as the research performed in the past.

Approaches that use pathomechanics have had mixed results in applied settings, mainly due to the complex interaction of variables outside kinematics. Athletes with mechanics outside of the typical norms found in research are not destined for injury, and those who are in normal ranges are not free from risk either. In my experience, a combination of workload, athlete age, fatigue, and mechanical patterns should be used collectively to keep athletes on the pitch and to extend careers.

Sports Recovery and Muscle Inflammation

The inflammatory response is very difficult to manage, since each day results in a possible direction down the wrong path of repair. Soft tissue, especially tendons, can remodel in a structurally weakened alignment, increasing the risk of rupture. Muscles that are chronically overused will find movement strategies and recruitment patterns that will continue to serve the demands of sport, but it frequently comes with a cost. Extended inflammation beyond normal time periods is a potentially damaging condition, especially to athletes who are genetically predisposed to pathologies. From the available evidence, it appears that delayed healing times occur when internal biochemistry and workload are not in balance, and a mere increase in temperature of 0.4 degrees Celsius can determine risk to specific muscle groups.

The inflammatory response to light exercise and heavy training is a normal condition. Only when the inflammation is accompanied by severe discomfort and followed by an impairment in sports performance or pain does the symptom pose risk. In clinical settings, physiotherapists should use thermography and reported symptoms and cross-validate those scores with primitive ortho examinations and imaging if necessary. Inflammatory responses that are beyond repair and enter the stage of degeneration can be seen by thermal scans.

Athletes who are managed properly will continue to have a typical inflammation pattern, but the severity and duration beyond normal will be reduced. Share on XThermography has potential for diagnosis, but for sports medicine, we (ThermoHuman) recommend using the approach for complementary purposes, including examination by a professional. Acute and chronic patterns of inflammation can guide support staff on how an injury or condition is trending. Over the years we have seen a distinct pattern for various injuries, ranging from acute tears to extended complex return to play challenges with the knee and hip. If tracked properly, inflammation patterns can be controlled and guided toward proper homeostasis. Athletes who are managed properly will continue to have a typical inflammation pattern, but the severity and duration beyond normal will be reduced.

A Case Study – Brazilian Soccer and Muscle Injuries

A question clubs ask me daily is whether sports thermography works with teams. My recommendation is for them to read the study from 2019 that utilizes our methodology2. The study, conducted in Brazil, monitored elite soccer players for two years. All athletes were tracked, and thermography was used to monitor the skin temperature of the athletes. The process was repeated for two years, and the results were supportive of thermography as a complementary solution for muscle injuries.

The authors conclude:

Findings from this study show that athletes who had muscle injury in the first year (2015) did not present lesions at the same site the following year. Thus, the early identification of the risk of injury, through thermography and the preventive protocol applied, was important because there was no reinjury. Thus, the severity of lesions and time away in 2016 was lower.

It may never be possible to prevent injuries. Sport is still entertainment, and the show must go on with or without its star. What we strongly believe is that sports thermography will reduce the rate and severity of injuries, and reinjury changes will be reduced with sports thermography. Success can be measured with more players available on the pitch or court, but also in the communication and documentation of services and complaints of the athlete. Adding in training regimens and GPS data may expose practice techniques that increase risk, but only if thermography bridges the connection between internal and external loading. IT will be up to the practitioner, not just the technology, for the use of thermography to assist in injury reduction.

Emerging Research and New Frontiers

The expectation is that camera sensitivity and capturing techniques will improve in the future. Currently, the quality of camera and protocols are more than adequate to conquer the challenge of reducing muscle traits with athletes. Adding multiple cameras, creating dedicated workstations, and automating reporting are all exciting directions for us. As more teams adopt ThermoHuman, the approach to monitoring will evolve with its popularity. In the meantime, using thermography frequently is an effective monitoring process for muscle recovery.

Research has already increased, as roughly half of all sports thermography studies were published over the last 10 years. The next 10 years will certainly be exciting and promising. Better controlled studies and experiments are expected to originate from the collaborations of sport science and sport medicine. Outside of football (soccer) and swimming, I expect additional research in basketball and American football, along with rugby, cricket, and baseball.

The most radical potential area for ThermoHuman and sports thermography is software. We have already released our second version, which dramatically improves both the analysis and the reporting. What ensures that thermography is valid and reliable is the protocol of capturing the athlete and the way the information is processed.

If you aren’t comfortable with the concept of thermography monitoring, a good start is maximizing the use of body soreness scoring often seen with monitoring software. Share on XIn addition, all users need to have an action plan after imaging. We recommend sports medicine departments and fitness coaches have an idea in mind before starting the implementation of sports thermography into their monitoring program. If you are not comfortable with the concept of thermography monitoring, a good start is maximizing the use of body soreness scoring often seen with monitoring software. The future of monitoring is going to be faster, smarter, highly more accurate, and more demanding.

Injury Reduction Is Not a Holy Grail

We concur that athletes will continue to suffer injuries in the future, and no program will be perfect. The most precious athletes are often those prone to injury, and we can make a significant impact on player availability using thermography alone. By adding the use of biochemical and other forms of tracking into the monitoring equation, you can ward off obvious risks with a cooperative environment. It will require more education to get the best practices refined with thermography in sport, but I am confident that more education can turn a good monitoring program into a superior solution.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Impellizzeri, Franco M., Marcora, Samuel M., and Coutts, Aaron James. “Internal and External Training Load: 15 Years On.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 2019;14(2):1-4.

2. Côrte, Ana C., Pedrinelli, André, Marttos, Antonio, et al. “Infrared Thermography Study as a Complementary Method of Screening and Prevention of Muscle Injuries: Pilot Study.” BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine. 2019;5(1):e000431.