[mashshare]

Strength and Conditioning has a strange and complicated relationship with pressing. After being told how important the movement is, we increasingly see our options limited due to apparent risks the movement brings. In the past, most programs would have included the bench press and military press religiously.

Outside of contact sports like rugby and American football, the bench movement is now treated as a pathology that can only cause harm. Certain popular powerlifting programs and dubious aspects of gym culture have conflated both horizontal and vertical presses.

Another issue is well-meaning coaches who mix protocols for general populations and specific athlete populations (for example, shoulder injury-prone groups like baseball players and cricketers) and then expand these to all athlete populations. Finally, the majority of research on overhead pressing and its relationship with the shoulder is rather negative.

While contested movements such as the squat, deadlift, and clean and jerk have plenty of research exploring their injury potential as well as their overwhelming positives, there is little performance data available for the overhead press and the push press. This means that trainers who lean strongly toward physical therapy have much information to quote when going against an ever-dwindling population of pragmatic coaches who still use the movement.

Defending the Right to Press Vertically

In this article, I focus mainly on bilateral overhead pressing; we find ourselves in a situation where the barbell overhead press has been disparaged nearly into extinction. Hilariously pointed out in a skit by Martin Rooney, this movement seemed to disappear from weight rooms and programming suggestions the world over. To a certain extent, this is because strength and conditioning is partially informed and led by strength sports. This relationship is largely symbiotic but also potentially perilous when we paint biases toward certain expressions of strength.

Video 1. Simple pressing is timeless, but it does require proper teaching and, more importantly, progressions. Not everyone can press vertically, but we shouldn’t remove the exercise from our inventory due to the very small group of athletes who can’t do the movement.

Inappropriate strength-based movements are often expropriated to athletes who focus on lifting maximum load instead of inducing maximum positive stress. This results in pattern overload, impingements, and injury risk. Coaches, in turn, kick back against this strength “convention” in an effort to reduce injuries that should only present in strength sport populations.

Coaches take movements that work well in injured and at-risk populations and use them as blanket pressing options for all populations. So now we see athletes doing anaemically loaded variations in an attempt to include “some kind of” pressing since it constitutes one of the major movement patterns. This may be fine for athletes who don’t need high-quality pressing actions as part of the sporting movement expression. But collision sports athletes need to stabilize the shoulder and extend the arm with high levels of force production.

Some practitioners utterly disregard the bench press as completely redundant for any athlete other than powerlifters, gym enthusiasts, and football players looking for good bench combine scores.

The overhead press had a bumpier journey. Influential figures suggested with gusto that it was potentially harmful to certain populations and outright said it should be abandoned for most athletes. We live in an age where coaches will often make withering proclamations about not doing x, y, or z–possibly to grab attention. While the sentiment is not wrong for certain populations, the zeitgeist swung away from overhead pressing, proclaiming it was problematic for all athletes. Don’t even dare mention the behind-the-neck press.

Bringing the Overhead Press Back from Near-Extinction

The overhead press was once part of the weightlifting trifecta and was later dumped due to the dubiousness of its performance with extreme loads. Mark Rippetoe has spent much time pushing against the trend away from overhead pressing and increasingly to derivative exercises. He places blame squarely on physical therapists and strength coaches who have over-medicalized movement.

Overhead pressing causes a thorough need for the system to be organized fully–toe to head–to accomplish the movement properly. This systemic stress offers several benefits to athletic populations, and it would be foolish just to discard it.

Overhead pressing causes systematic stress and offers several benefits to athletic populations, says @WSWayland. Share on XJonathan Mike states that, “This complex, multi-joint movement has potential for heavy loading, along with the incorporation of multiple muscle groups, across multiple planes of movement.” And further that, “Nearly all groups of populations would benefit from some improvement in upper body strength and stabilization from the use of a multi-plane, multi-joint exercise that can be loaded to coincide with any strength, power, or hypertrophic goal an athlete may have. The versatility of the SBOHP also allows its use in almost any stage of an athlete’s annual periodization cycle.”

In the same NSCA article, Mike also explores the movement’s execution, which differs among organizations. The Olympic lifting community has never really abandoned the movement, and they happen to be an absolute goldmine of content for pressing variations.

Rippetoe often argues that it’s the lack of overhead pressing in early exercise selection that makes the movement problematic. By the time athletes approach heavy pressing, they’ve acquired restrictions and immobility issues that stop them from performing it properly. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

Why is pressing force development vertically and horizontally so important?

There’s a strong relationship between upper body strength and limb speed, particularly in heavy pressing horizontally and vertically. This is crucial for sports that require high limb speeds, including boxing, baseball, golf, and handball. Limb force production is also crucial for the lower velocities that occur in combat and collision sports. Coaches of rugby, wrestling, judo, and other collision sports–where players must forcefully press away from opponents in several directions–should monitor strength development in both actions.

Heavy #pressing horizontally and vertically is crucial for combat and collision sports, says @WSWayland. Share on XSoft tissue issues, though, are a concern in collision and non-collision sports, and we have a plethora of exercise options thanks to proactive coaches. But athletes are disserved by languishing on bottoms-up kettlebell presses, landmine pressing, and half kneeling presses. We see a scenario where stability is valued above force production, which is a perfectly legitimate relationship.

If the athlete, however, never gets beyond learning to stabilize due to minimal dosing, potential force production will never develop. As with any exercise variant, once we’ve established stability and competence, we must pursue the intensity and stimulus brought by heavy pressing. The key is to find constructive press variations that allow for intensity.

We load the overhead press intensively and use it to develop power from head to toe, says @WSWayland. Share on XI outline below six bilateral pressing methods we use in our programming. Implementation comes early in our athletes’ training cycles, and we encourage our youth athletes to press with a dowel in warm-up and training. By establishing the pattern early, we don’t have to undo negative postural habits or work to overcome mobility restrictions built up via preferential pressing habits. The main focus is the ability to press out from disadvantaged positions and decelerating control. We load intensively and use the movement to assist power development from head to toe.

The Overhead Press: A Staple and Foundation

The standard overhead press confers most of its benefits–isometric work from the lower body and full engagement from trunk and extremities–with high loads, which made this movement a popular staple in the past. Excellent explanations of the movement exist all over the web, including an exploratory article in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning by Kroell and Mike (see References), Dr. Yessis’ website, and explanatory videos by press advocate Mark Rippetoe.

Yessis goes further into sporting application: “The military press is great for development of the upper and lower portions of the middle of the back. The combination of joint actions involved in the military press is used in a multitude of sports, as for example, in the clean and jerk and snatch in weightlifting and in various movements in gymnastics….The actions and muscle development are also important when throwing different punches in boxing, in the shot-put, and in handstand push-offs in gymnastics.”

Push Pressing Like a Pro

I extensively use an option with push press that allows for lower body and upper body sequencing and improves strength and power in both. “The mechanical demand of the push press is comparable with the jump squat and could provide a time-efficient combination of lower-body power and upper body and trunk strength training.” This comes from the shallow, violent redirection of energy into the barbell by using a dip. It effectively provides a 1/6-1/8 jump squat of sorts into a press.

We know that improving lower limb speed in running athletes is probably best done by performing jump squats. But for athletes who want to improve limb speed and stability in the upper and lower body, the push press is very useful. The transfer from foot to hand is very helpful for striking athletes–think of stiff-arming opponents in collision sports, striking, and framing limbs to create space. It’s the final extension that helps collision athletes; the press out is desirable versus, say, the jerk which should lack a press out.

The final extension in the push press helps stiff-arm opponents in collision sports, says @WSWayland. Share on XHeavy push pressing allows us to approach heavy upper body work in an auto-regulatory fashion. When monitoring my athletes, I often notice that poor push press performance indicates high levels of CNS fatigue leading to failure during the push or peripheral fatigue causing failure to complete the lockout.

I often program push pressing as a 90%+ upper body option for doubles, in contrast to horizontal pressing on other training days. I have greater completion levels and responsible autoregulation in a group setting versus, for example, bench pressing with 90%+ loading.

Behind-the-Neck Press: An Option for Some

The behind-the-neck press (BNP) is just about extinct in most weight rooms. I still see Olympic weightlifters perform numerous variations of this lift with the likes of Dimitry Klokov promoting wide grip variations from a dead start. I’m not suggesting anyone start there.

During my early lifting career, I was introduced to the lift as important for healthy shoulders. I was later told, while still a young athlete, never to perform it because it “was bad for your shoulders.” I’ve since used it regularly with my athletes. The BNP is a viable corrective exercise when loaded lightly, and a great shoulder strength promoter when pattern and mobility are solid with decent loading.

Video 2. Not every athlete can press, and far fewer athletes should press behind the neck. Regardless, those who can should not be stopped by those who overreact or the population who can’t do the exercise.

It’s precisely the effect on the rhomboids, infraspinatus, teres minor, and supraspinatus that allows for better scapular retraction and dynamic stabilization. If an athlete cannot perform the BNP or has pain doing so, this often indicates mobility limitations, often at the shoulder or T-spine. In this sense, we can use the BNP in an assessment. While I’m not a fan of movement screens, I do like to use some exercises to highlight restrictions. Starting out with a broomstick, band, or lightly loaded barbell and progressing from there can work wonders.

Eccentric Overhead Pressing

I rarely see force acceptance trained on the overhead press. Because overhead pressing is largely considered a concentric activity, we often see athletes eccentrically drop the weight rapidly to use the stretch reflex at the bottom of the movement. When I was a young athlete, a few bodybuilders showed me eccentric presses, and I abandoned them in favor of press/jerk variations as I learned more about Olympic lifting.

I began to consider it seriously as I became exposed to triphasic training. Eccentric overhead pressing requires high levels of shoulder and trunk stability. I’ve decided we should perform more shoulder work eccentrically to aid injury prevention.

Video 3. A slight cheat with the legs can quickly make a heavy press into an eccentric variation if instructed properly. Those who can push press will know how to deliver just the right amount of assistance concentrically.

The lateral and medial deltoids respond well to high tension levels, and the eccentric overhead press is a great way to build intensity without the high loads some worry about. If the focus is solely on upper body stabilization, we can perform it while seated. Eccentric push presses are a formidable supramaximal eccentric option but, obviously, we must apply this movement with prudence. The exercise lets us merge this explosive lower body option with eccentric upper body work, a worthwhile time-efficient option.

There’s also the eccentric BNP which will definitely break the rules. I use it to encourage strong overhead stabilization and scapular depression by recruiting the upper back, traps, and posterior shoulders. It’s not dissimilar to a back squat. Worked up overtime, athletes can perform these movements fairly heavy despite being unconventional.

Much like the hand supported split squat and the Romanian deadlift, we can apply maximum strength outside standard movement paradigms across different movement contexts and still confer benefits.

Trap Bar or Jammer Overhead Press

Trapbar and Jammer presses are increasingly popular as a pressing variation. It’s my bilateral pressing option for those who have persistent shoulder trouble with standard overhand grip. By going neutral, they can keep pressing with a highly loadable movement. There’s also no need to move the head out of the way with the trap bar press. The neutral position takes pressure off the shoulders, wrists, and elbows.

Video 4. The Trap Bar or Hex Bar offers two unique benefits, a neutral grip and removing the head clearance needs of the lifter. In addition to traditional loading, accommodating resistance is possible with the specialized bar.

Obviously, the width, size, and handle types on your trap bar will need some testing if you’ve never tried it before. I suggest using the low handles since the high handles will turn the movement into a glorified bottoms-up press.

Jammer arms are more rare, but they’re a tool that’s lurked in the weight room for decades. Manufacturers are now finding creative ways to make them compact, versatile, and more ergonomic than, for example, a double landmine press. The lever arm changes the nature of the movement, and we can perform push presses, banded, and eccentric presses with ease.

Oscillatory Pressing

Slightly more outlandish is the oscillatory press. By adding rapid acceleration and deceleration at the bottom of the movement for timed periods or a desired number of oscillations, we create rapid dynamic stabilization into an explosive press out. The condensed range of motion leads to increased tissue tolerance which, for shoulders, can be extremely useful. Oscillatory sets are short because they’re very taxing on the stabilizing structures in the shoulder and upper back. The oscillation should be 2-3 inches. After the oscillation, press out as fast as possible and pull the bar back down as quickly as possible.

Video 5. At first glance, oscillatory pressing may look like a variation without function, but the exercise is an invaluable option. Focusing on the transition of the rep will yield dividends in peaking down the road, but only when the athlete is ready.

I encourage those who are unfamiliar with the exercise to start the movement from the top to emphasize the idea of pulling the bar down. I use this variation with any of the movement options discussed.

Development and Sequencing

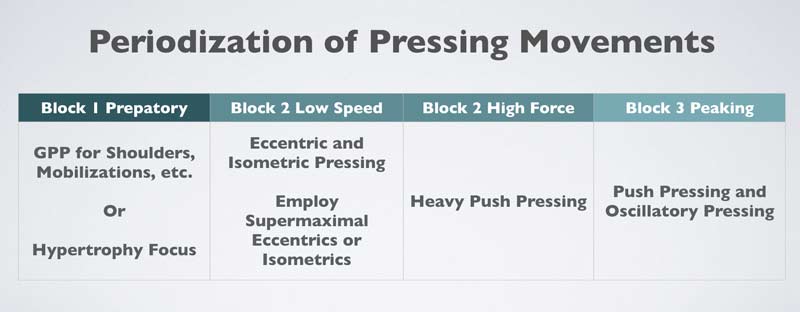

Sequencing these movements follows a simple pattern of GPP/Hypertrophy, high-force low-velocity movements and then peaking with high-velocity low-force movements. The fight over the press’s application is between pragmatic strength coaches versus coaches with physical therapy leanings. The context under which the employ their ethos is important to the debate.

Many who discourage overhead pressing and pressing in general seem to be those who deal with athletic populations that commonly have issues with this particular movement. The blanket statements these coaches espouse are always problematic. Understandably, mobility limitations and issues throughout the upper limbs make this a movement many avoid–the idea of accelerating high loads overhead worries some coaches.

Others may turn their noses up because it doesn’t fit popular convention, and the desire to be seen doing the right things can be powerful. Sometimes I wonder how different things would be if the front squat were a strength sport lift, much like if the overhead press had never been tossed out of the Olympics.

References

- Fair J. “The tragic history of the military press in Olympic and world championship competition, 1928–1972.” J Sports Hist 28(3): 345–374, 2001.

- Vernillo G, Temesi J, Martin M, Millet GY (2017). “Mechanisms of Fatigue and Recovery in Upper versus Lower Limbs in Men.”

- Kroell J & Mike J (2017). “Exploring the Standing Barbell Overhead Press. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research

- Van Dyke M. “OC Training and Partials.”