Cody sits down and goes through his life story from the very beginning including:

• Upbringing

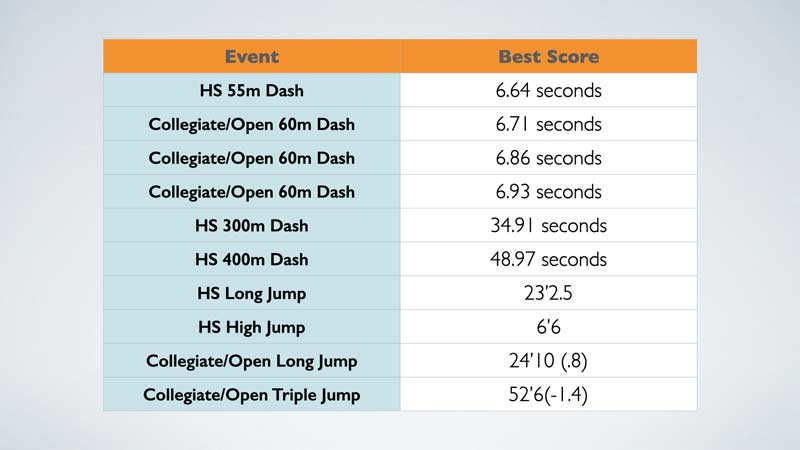

• High school sports & events

• College playing career

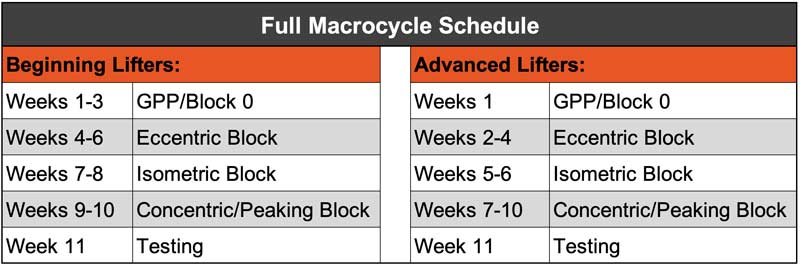

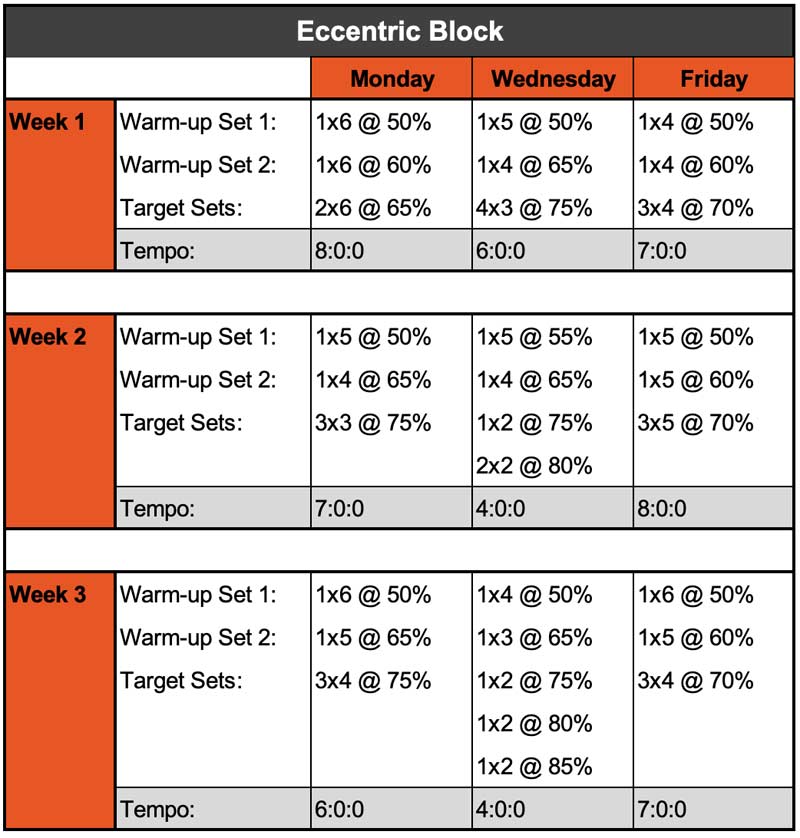

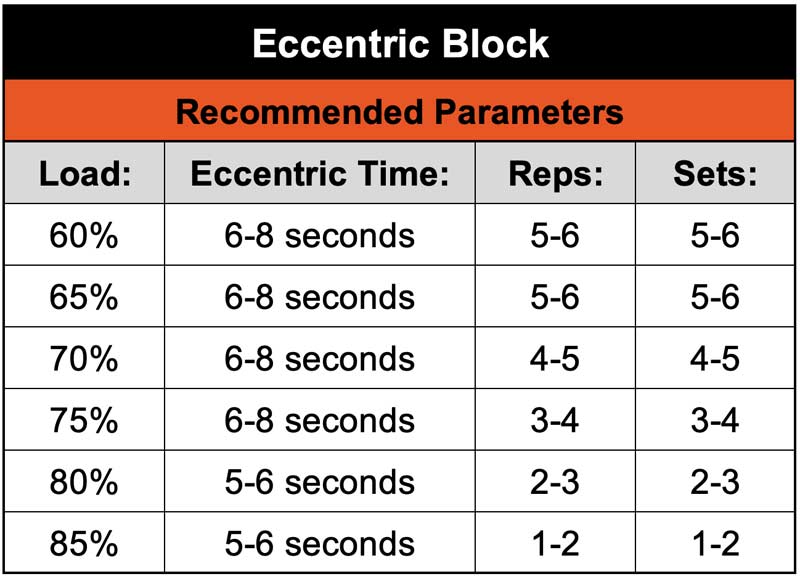

• Getting into strength and conditioning

• Major life decisions

Listen in as Cody gives you a snapshot of his life journey thus far.

Connect with Cody:

Cody’s Media:

IG: @clh_strength

Twitter: @clh_strength

Email: [email protected]