By Kyle O’Toole & Mike Young

Whether performing a change of direction on the field or a squat in the weight room, an athlete’s ability to generate force eccentrically is vital to their ability to decelerate before forcefully reaccelerating in another direction. Eccentric strength is an important and often overlooked physical component for athletes to improve if they want to become faster or more powerful in their sport.

Unfortunately, eccentric training is often not administered appropriately to optimize anticipated adaptations. When administered inappropriately, athletes will not benefit from the desired training effects due to failure to reach their eccentric training threshold. This is most noticeable toward the latter portion of the eccentric training continuum while attempting to reach eccentric overload. Eccentric overload occurs when peak eccentric forces and peak eccentric power output are higher than what we can produce during a concentric action. If the external forces or the speed of the movement are not sufficient to reach eccentric threshold, then an eccentric overload is not produced.

Eccentric strength is an important and often overlooked physical component for athletes to improve if they want to become faster or more powerful in their sport. Share on XCoaches should understand that to attain an eccentric overload, the athlete must get to a point where they use loads that are higher than their concentric one repetition maximum (1RM). Furthermore, the risk of injury may increase if they don’t follow appropriate progressions. Since many of the more advanced eccentric exercises can involve both a high load and a high rate of loading, athletes need appropriate preparation to be able to safely handle them.

Administered properly, eccentric training maximizes the development of physiological properties that reduce the likelihood of injury and increase athletic performance. Eccentric training provides a training stimulus that builds muscle better suited for explosive athletic movements. In this way eccentric training greatly enhances speed and power development.1,2

What Is Eccentric Training?

Eccentric actions occur when passive muscle tissues lengthen while resisting an external force or load. Muscles are lengthening while contracting. The other two actions that occur are concentric actions (muscles shortening as they contract) and isometric actions (no changes in muscle length). Eccentric contractions occur when muscle fibers lengthen, and the passive elements exert force to resist being deformed. It is this eccentric capacity, or the ability of the muscles to resist forces while lengthening, that helps create faster, more explosive athletes.

Examples of common eccentric training modalities:

- Submaximal slow eccentric phase lifts.

- Weight releaser training.

- Flywheel training.

- Depth drop jumps.

Eccentric training can enhance joint stability, increase the efficiency of force transfer through joints, and improve deceleration abilities.3,4 If you are involved in a sport where you stop and go, plant and cut, or accelerate frequently, then eccentric training should be a regular part of your strength training program.

If you are involved in a sport where you stop and go, plant or cut, or accelerate frequently, then eccentric training should be a regular part of your strength training program. Share on XWe are much stronger in our ability to produce force eccentrically than concentrically. In other words, we are capable of producing more force while yielding than we are when overcoming those forces. Research has shown that we are up to 160% stronger in the upper body eccentrically and up to 80% stronger in the lower body eccentrically.5 For this reason, traditional strength training methods, which are focused primarily on concentric actions, are not an optimal stimulus to enhance eccentric capacity. Training that specifically targets eccentric capacities has been shown to improve measures of power and rate of force development more than traditional, concentric-focused training1 while producing similar outcomes on maximal strength, muscular hypertrophy, and injury reduction.4,6,7

Eccentric Training Progression

You should implement eccentric training throughout your annual strength training program. Most of the strength training should center around developing physical capacities (strength, speed, endurance, flexibility, coordination) through traditional strength training, but you should also incorporate eccentrics regularly throughout the year. Just like traditional strength training, eccentric strength training should follow a structured approach that progressively builds strength and power over time. Because fast/maximal eccentrics require extremely high loads and intensities indicative of sport, it is important that athletes regularly incorporate an eccentric training stimulus on a weekly basis. This ensures the passive tissues (tendons and ligaments) remain resilient enough to endure the higher demands in intensity being placed on them in future training and during competition.

We lay out a systematic approach to eccentric training below. Coaches will want to note that eccentric training should be used as a tool to complement traditional strength training. If we were to use percentages, roughly 80-85% of the yearly training would focus on traditional strength training designed to increase physical capacities. The remaining 15-20% would focus on eccentric strength training designed to further increase eccentric capacity.

Not all athletes will need to move entirely through the continuum. As strength and conditioning coaches, we need to decide what role eccentric strength plays in execution for sport. In a sport like track and field, where hundredths of a second separate the fastest athletes in the world, progressing through the entire continuum and emphasizing shock loading strategies could ultimately influence a podium finish.

The progression toward fast/maximal eccentric loading starts with submaximal isometrics and evolves into maximal isometric work before advancing into slow submaximal eccentric training. Isometric muscle actions are essential for explosive motion. For the joints to be able to move in rapid succession, both the passive and contractile elements within muscle need to be able to efficiently transfer energy and conduct locomotion at a high rate. It is for these reasons that isometric strength is addressed before prioritizing eccentric strength development.

In practice, this progression targeting eccentric strength development in the posterior chain might look like this:

- Athlete performs a standard Romanian deadlift (RDL) using moderate loading.

- Athlete performs an RDL with a controlled eccentric phase.

- Athlete performs a deadlift concentrically and an RDL on the eccentric phase (thus permitting greater loading than the athlete could safely perform with an RDL concentrically). This is known as the strong-weak method.

- Athlete performs a bilateral RDL concentrically but a single leg RDL eccentrically (again permitting greater loading on the eccentric phase). This is known as the 2 up 1 down method.

- Athlete performs an RDL where they drop the weight or allow it to “free fall” from the top of the movement and rapidly decelerate it at the bottom of the movement using stiffness through the posterior chain. This is an example of shock loading.

Submaximal Isometrics

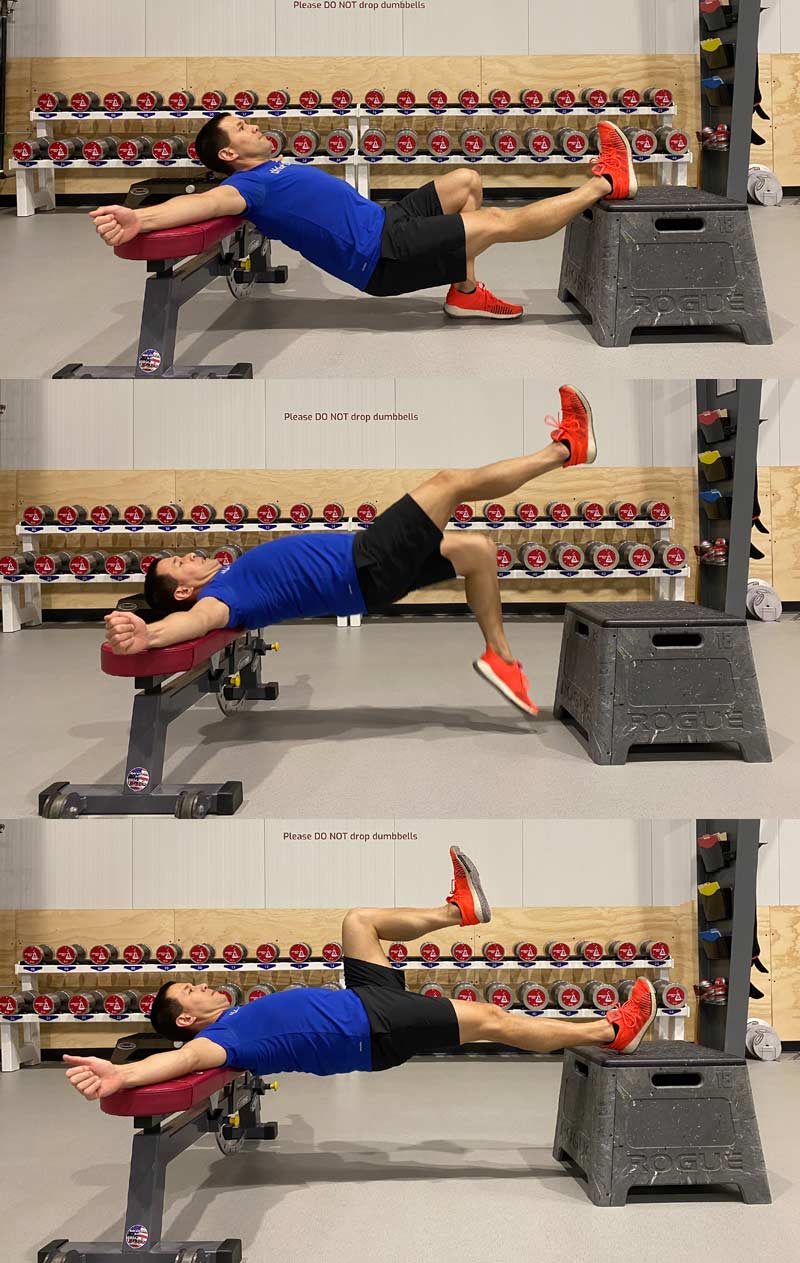

Starting with submaximal isometric exercises is a safe first step that all individuals can take in the progression to more advanced and focused eccentric training. Submaximal isometrics are characterized by performing intentional pauses at one or more positions in the range of motion while using submaximal loads that can be overcome when desired. Submaximal isometric exercises build strength at specific positions and are a first step toward maximal isometrics. An example can be seen in image 1.

Maximal Isometrics

Unlike submaximal isometrics, with maximal effort isometrics the athlete is unable to overcome the load. In other words, the athlete makes a maximal attempt to move an immovable object. It is absolutely critical that they perform these exercises with maximal intent. Examples of these exercises include pin presses or pin squats into the rack. These exercises are best performed near the end ranges of motion to more specifically train the specific joint positions associated with athletic movements.

Slow/Submaximal Eccentrics

Submaximal eccentrics are characterized by performing exercises with an intentionally slow eccentric phase using loads that the athlete can overcome on the concentric phase. These exercises will emphasize a slow and controlled descent through the eccentric portion of the lift. The eccentric phase of these exercises should last 3-5 seconds.

Fast/Maximal Eccentrics

When performing maximal eccentric training, remember to work with loads that are above an athlete’s concentric training max (greater than 100% 1RM). Maximal eccentric training increases type II muscle fiber size and enhances an athlete’s ability to express their strength at higher velocities.

Eccentric Shock Loading

The final and most demanding step in eccentric-focused training is eccentric shock loading. Although this category includes commonly used plyometric exercises, it also includes specialized strength training activities characterized by the rapid imposition of a high load that forces the athlete into an eccentric action. These loading parameters are especially challenging and mimic the actions and velocities witnessed in sport.

Incorporate Eccentric-Focused Work

An athlete’s ability to generate force eccentrically is critical to performance and injury prevention. As with any performance indicator, it is important that you adequately address eccentric strength in training. Traditional weight room protocols may not sufficiently develop eccentric capacity. As such, it may be beneficial for athletes and coaches to incorporate eccentric-focused methods into their yearly training program. When incorporating any new method, but especially one as physically demanding as eccentric-focused training, it is advised that coaches follow best practices of planned and progressive overload.

We suggest incorporating eccentric-focused work into strength training programs regularly and consistently throughout the entire year of training. Share on XThe progression we have provided will allow athletes to safely handle the higher loads and velocities associated with maximal effort eccentric training. We suggest incorporating eccentric-focused work into strength training programs regularly and consistently throughout the entire year of training. Focus on progressively building eccentric capacity and do not rush through the progressions. Allow plenty of time for athletes to recover from the prior training session and slowly build their threshold for more training. Eccentric training will build an athlete’s ability to resist forces and increase their speed, explosiveness, and change of direction ability in their sport.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Douglas J., Pearson S., Ross A., and McGuigan M. “Chronic Adaptations to Eccentric Training: A Systematic Review.” Sports Medicine. 2017;47(5):917-941. doi:10.1007/s40279-016-0628-4

2. Friedmann-Bette B., Bauer T., Kinscherf R. et al. “Effects of strength training with eccentric overload on muscle adaptation in male athletes.” European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2010;108(4):821-836. doi:10.1007/s00421-009-1292-2

3. Papadopoulos C., Theodosiou K., Bogdanis G.C., et al. “Multiarticular Isokinetic High-Load Eccentric Training Induces Large Increases in Eccentric and Concentric Strength and Jumping Performance.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2014;28(9):2680-2688. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000456

4. Roig M., O’Brien K., Kirk G., et al. “The effects of eccentric versus concentric resistance training on muscle strength and mass in healthy adults: a systematic review of meta-analysis.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2009;43(8):556-568. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.051417

5. Hollander D.B., Kraemer R.R., Kilpatrick M.W., et al. “Maximal eccentric and concentric strength discrepancies between young men and women for dynamic resistance exercise.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2007;21(1):34-40. doi:10.1519/R-18725.1

6. Fleck S. and Schutt R. “Types of strength training.” Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 1983;14:449-458.

7. Roig Pull M. and Ranson C. “Eccentric muscle actions: Implications for injury prevention and rehabilitation.” Physical Therapy in Sport. 2007;8(2):88-97. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2006.11.005

Mike Young, PhD, is the Director of Performance for Athletic Lab, the North Carolina Courage, and North Carolina FC. He’s also the head coach of Athletic Lab Track Club. In individual sports, Mike has coached athletes to international teams in four sports (weightlifting, skeleton, bobsleigh, and track and field). In team sport settings, Mike has worked in the MLS, USL, and NWSL and most notably has assisted the winningest women’s soccer team in American history and more than a dozen World Cup players.

Mike Young, PhD, is the Director of Performance for Athletic Lab, the North Carolina Courage, and North Carolina FC. He’s also the head coach of Athletic Lab Track Club. In individual sports, Mike has coached athletes to international teams in four sports (weightlifting, skeleton, bobsleigh, and track and field). In team sport settings, Mike has worked in the MLS, USL, and NWSL and most notably has assisted the winningest women’s soccer team in American history and more than a dozen World Cup players.