[mashshare]

There is seemingly no end to the articles and videos by sports coaches, personal trainers, and strength coaches who contend that partial Olympic lifting exercises are just as good, if not better, than the full movements. As a weightlifting coach, I’m here to tell you that their opinions cannot be backed by science and they are doing their athletes a disservice by promoting such nonsense.

The first ridiculous argument I’ve heard is that most athletes cannot be expected to perform full squat cleans (and certainly not snatches!) because they lack the flexibility to achieve these positions. Seriously? What they are saying, in effect, is that they have identified flexibility deficiencies in their athletes and their solution is to avoid exercises that can fix them! Let me expand on this point.

Weightlifting and Flexibility

In the field of corrective exercise, one of the most popular tests to assess flexibility and muscle balance is the overhead squat. In fact, in a class on corrective exercise for my master’s degree, we had to complete a modular about the overhead squat. We learned how to use the overhead squat as an assessment tool and how to correct deficiencies. Let me give you a few examples.

Weightlifting is a sport that not only requires exceptional flexibility, but also develops it. Share on XIf the knees buckle inward, this could suggest tightness in the thigh adductors or weakness in the glute medius. If the knees flare outward excessively, this could suggest tightness in the piriformis (a muscle involved in hip rotation) or weakness in the thigh adductors. Using this information, the trainer could resolve these faults by having the athlete stretch the muscles that are tight and strengthen those that are weak. Rather than prescribing a laundry list of stretches and corrective strength training exercises, how about simply performing overhead squats!

I’ve been involved in the sport of weightlifting for over four decades, and I can assure you that most weightlifting coaches will simply start new lifters with overhead squats—that’s it! After a few sessions, they will progress into power snatches and then full snatches; however, exceptional athletes can often hit good positions in the full lifts during their first training session. The takeaway here is that weightlifting is a sport that not only requires exceptional flexibility but also develops it.

Shearing Force and Injury Risk

Now I’d like to address the belief that full cleans should be avoided because the knees should not extend in front of the toes during squats and that only weightlifters should bounce out of the rock-bottom catch position in the clean. One reason I hear is that both of these practices create harmful shear forces that try to pry apart the knees.

First, having the knees extend past the toes is a characteristic of natural human movement. Take a big step forward and freeze in the split position. Now look down at your back knee—unless you’re a centaur or were raised by kangaroos, your knee will be positioned in front of your toes. That settled, let’s move on to the argument that squatting all the way down and bouncing out of the bottom position is harmful.

When I starting writing training articles in the ’80s, I had to continually address the myths that full squats were bad for the knees and that only weightlifters should bounce out of the bottom position of the clean. Some of this misinformation could be attributed to a controversial study published in 1961 that said full squats—in contrast to parallel squats—could increase knee injuries by creating instability in the joint.

The study was done by college professor Karl Klein and medical doctor Fred L. Allman, Jr. To test for knee laxity, a device was placed on the subject’s knees and the examiner applied pressure and took a reading from a gauge attached to it. The subjects included some who did parallel squats and some who did full squats.

Two of the subjects in the study were Bill Starr and Tommy Suggs, both elite weightlifters. Terry Todd, in an article about this study, noted: “Suggs recalled that the apparatus Klein used to measure instability in the knee contained no device to determine how hard Klein pushed or pulled to establish a reading on the gauge over the knee, which registered the knee’s looseness. Suggs also confirmed that Klein asked the lifters whether they were deep squatters before testing them.” There’s more.

In a letter to the editor that was published in the August 1963 issue of Strength and Health magazine, Starr said many lifters stopped letting them experiment on them “…since he was exerting so much pressure that he hurt their knees,” and “…he always asked the subject beforehand, not afterward, whether he did full squats.” Further, Todd said subsequent research using a copy of Klein’s testing device “failed to observe significant difference between the full squat and the half squat in their effects on the knee.”

Does bouncing out of the squat cause high shearing forces that can, in extreme cases, rip the tendon off of the patella? First, consider that there is an inverse relationship between compressive and shearing forces—the deeper you squat, the higher the compressive forces and the lower the shearing forces.

A former competitive weightlifter, Dr. Arron Horschig holds a doctorate in physical therapy and has written extensively about squats. Horschig says the stress on the ACL is greatest during the first 4 inches of the squat descent (about 15-30 degrees), which is the angle that lifters often receive the bar when catching a power clean. When you add to this the technique often employed by many athletes of jumping their feet out hyper-wide such that the knees buckle inward, the stress on the knee ligaments increases even more.

It’s also important to realize that fascia tissue such as tendons are not rigid, fragile bands that need to be reinforced with athletic tape and braces to deal with the high stresses of athletic competition. Tendons act as biological springs that elongate and shorten to assist the muscles in producing movement and to protect the joints. If you limit yourself to powerlifting-type squats or partial Olympic lift movements such as the hang power clean, these tissues may lose their elastic qualities. They become stiff, like an old rubber band, and may make the athlete more susceptible to injury.

Think about it—why are the majority of ACL and ankle injuries non-contact? Did your favorite NFL or NBA player rupture their Achilles or tear knee ligaments when they did a sudden cut because they didn’t have an extra layer of that space-age sports performance tape? Contrast this to weightlifters who put their Achilles tendon under high levels of stress with heavy loads.

Despite lifters wearing low-top shoes that provide little lateral support, the prevalence of ankle injuries in the sport of weightlifting is nearly zero—I’ve never seen one. Is it possible that such artificial reinforcement affects the ability of the tendon to function properly, and thus puts more stress on the joint? And, as Jud Logan will tell you, there is also the issue of improperly performed exercises.

Logan is one of the most decorated hammer throwers in the U.S., having made four Olympic teams. At one point in his career he had severe tendinitis in his knees and was advised to squat high to decrease the shearing force; Logan said these partial squats made the condition worse. He ended up resolving the problem by simply performing full squats. It’s great to be strong, but it’s equally important not to practice strength training methods that adversely affect the elastic properties of the connective tissues. This is not to say that an athlete should never perform partial-range exercises, but that they need to keep their joints healthy by also performing full range exercises.

Don’t use strength training that adversely affects the elastic properties of the connective tissues. Share on XStaying on this subject a bit longer, Professor Yuri Verkhoshansky was inspired to create his system of classical plyometrics because he found that overloading the quads with partial squats caused back problems with his jumpers. Using gravity as the primary form of resistance during depth jumps, he was able to overload the legs. Consider too that in his Block Training System for volleyball players to improve their vertical jump, the fourth (and most intense) level of training consisted of depth jumps and the Olympic lifts, whereas resistance exercises such as squats were relegated to the second level.

How Pulling Techniques Impact the Lumbar Spine

Another point to consider is that the pulling technique used by non-weightlifters to perform hang power cleans seldom resembles the technique used during the full lifts. Most often, those who practice only hang cleans tend to start with the shoulders well in front of the bar so they can use the back as a lever to produce force. The usual result is that the bar follows a large arc, such that the weight loops back towards the athlete, creating large shearing forces on the spine. This technique would be fine if you were training horses.

A horse’s spine rests horizontally on the animal with a structure that resembles a cantilever bridge, and this suspension system enables us to ride them without causing damage. A human’s spine is a column-like structure that is better suited for handling vertical compressive forces (think about this if you are considering resting a heavy barbell across your pelvis to do hip thrusts). Compound that with the stress of heaving extremely heavy weights over a short range of motion and creating a sudden shock on the spine and, well—ouch!

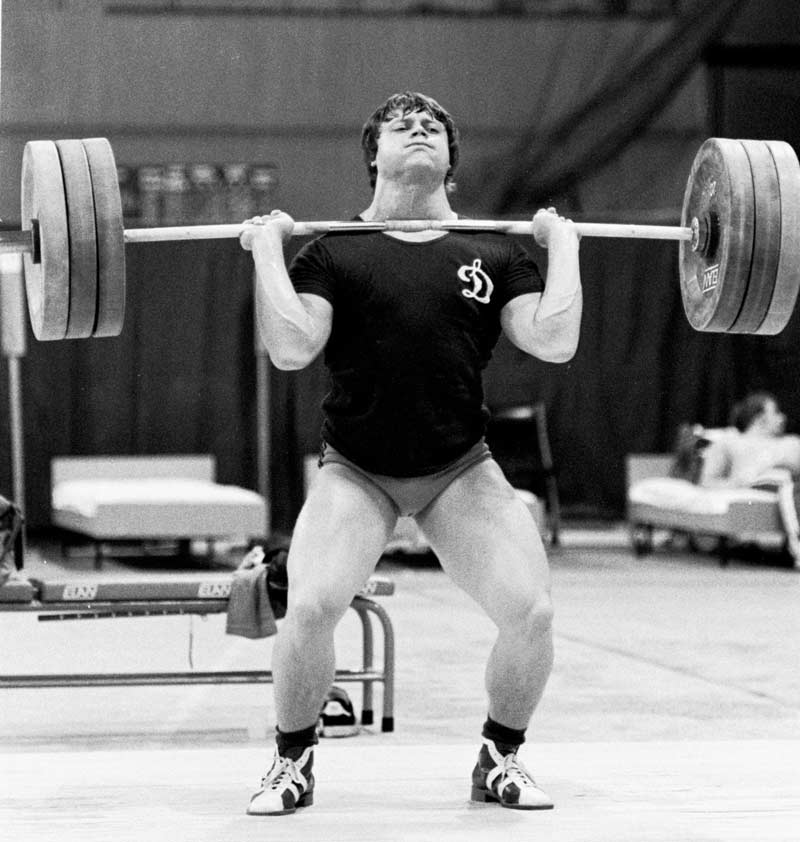

If you look at the Russian weightlifting manuals translated by sports scientist Bud Charniga, you’ll see that these coaches taught a pulling method in which the shoulders move in front of the bar after it passes the knees. This style increases and prolongs the loading on the lumbar spine, and is why the Russian lifters needed to perform a high volume of work to develop the erector spinae muscles to compensate.

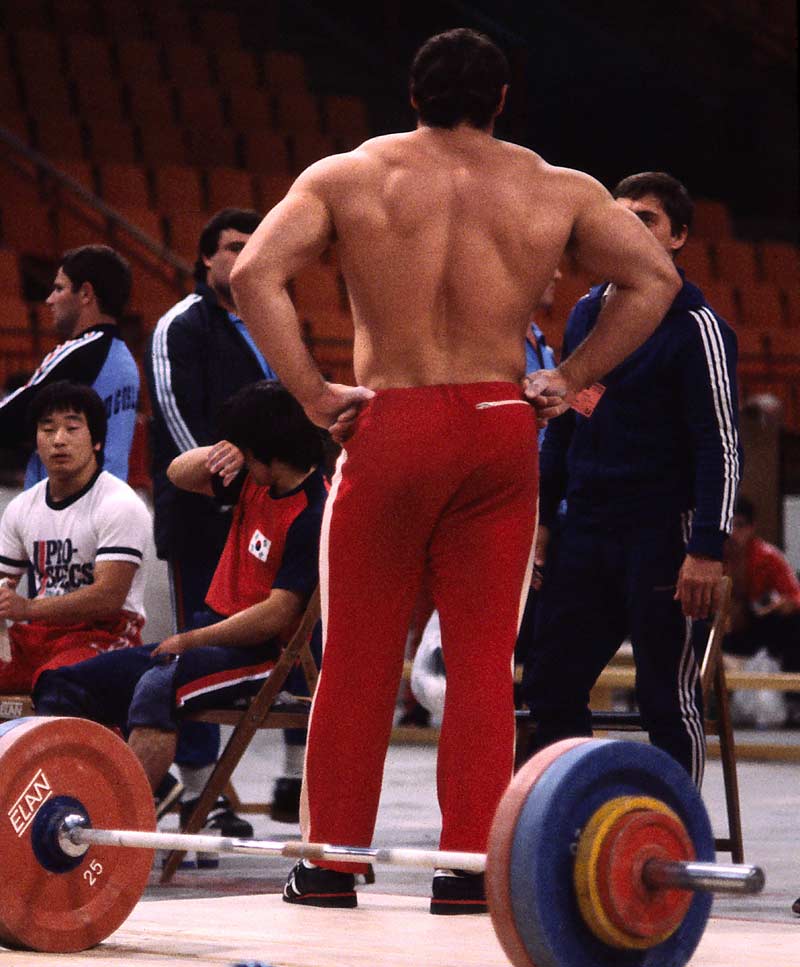

In contrast, many elite Chinese lifters (especially the women) use a spine-friendly technique. Not only do the shoulders not extend in front of the knees during the pull to the knees, but they are actually behind the bar when it reaches mid-thigh (i.e., the start position of the hang power clean). Perhaps, as a result, such modifications in pulling technique is one reason the Chinese have become the dominant force in weightlifting for the past several Olympic cycles, whereas the once powerful Russians have suffered a gold medal drought?

Absorbing Force in Contact Sports

Since most athletic movements don’t require athletes to drop into a full squat, what is the advantage of doing a full clean? The answer is that part of athletic performance is not just being able to apply force, but to also absorb and redirect force—in effect, training the athlete to be able to bend, but not break.

Part of athletic performance is not just being able to apply force, but also absorb and redirect it. Share on XAn example of the need to be able to absorb and redirect force would be the skills of an offensive lineman in football. These athletes don’t just apply force in a forward direction, but are also required to absorb the forces imparted on them by defensive players who are trying to get to the quarterback and other players. Training with a football sled would certainly help a lineman apply a greater amount of force, but full cleans will also train the body to absorb such forces—putting on the brakes, so to speak.

Another good example of the need for such “yielding strength” is boxing. There is much more to the sport of boxing than just being able to throw punches—you have to be able to take a punch. Watch a Floyd Mayweather highlight video. With a 50-0 record, Mayweather is one of the greatest fighters of all time. One reason for his success is that it is extremely difficult to hit him, and when his opponents manage to do so, the blows are often redirected or reduced in impact.

As an apparent compromise, some strength coaches say that they can ensure complete muscular development by supplementing hang power cleans with heavy deadlifts. Sorry to disappoint, but increasing strength at slow speeds doesn’t necessarily mean that strength can be demonstrated at fast speeds. Isokinetic studies have shown that increasing strength at fast speeds improved strength at fast and slow speeds, but increasing strength at slow speeds only improved strength at slow speeds. This is one reason why studies comparing Olympic lifting exercises to powerlifting exercises show that the Olympic lifts are superior for improving jumping and sprinting ability.

Increasing strength at slow speeds doesn’t mean that strength can be demonstrated at fast speeds. Share on X

Of course, there are many weightlifters who perform power cleans from the floor in training, but they consider them more of an assistance exercise (and to give them a break from the monotony of performing just the classical lifts). This is a much different approach than only performing power cleans, or worse, power cleans from the hang. Also, consider that these weightlifters might be successful not because they do power cleans, but in spite of it!

Athletes in many sports have embraced explosive exercises with resistance, along with hardcore fitness enthusiasts involved in “boot camp” workouts. But rather than getting partial results with inferior versions of the Olympic lifts, such as the hang power clean, consider doing the lifts the way they were intended.

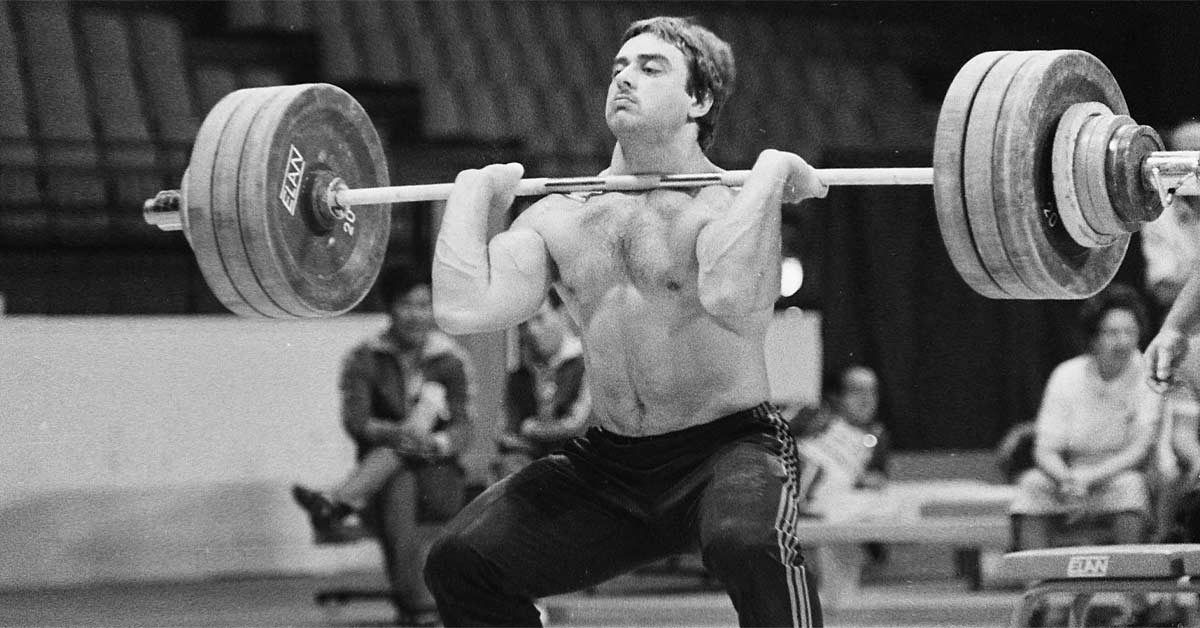

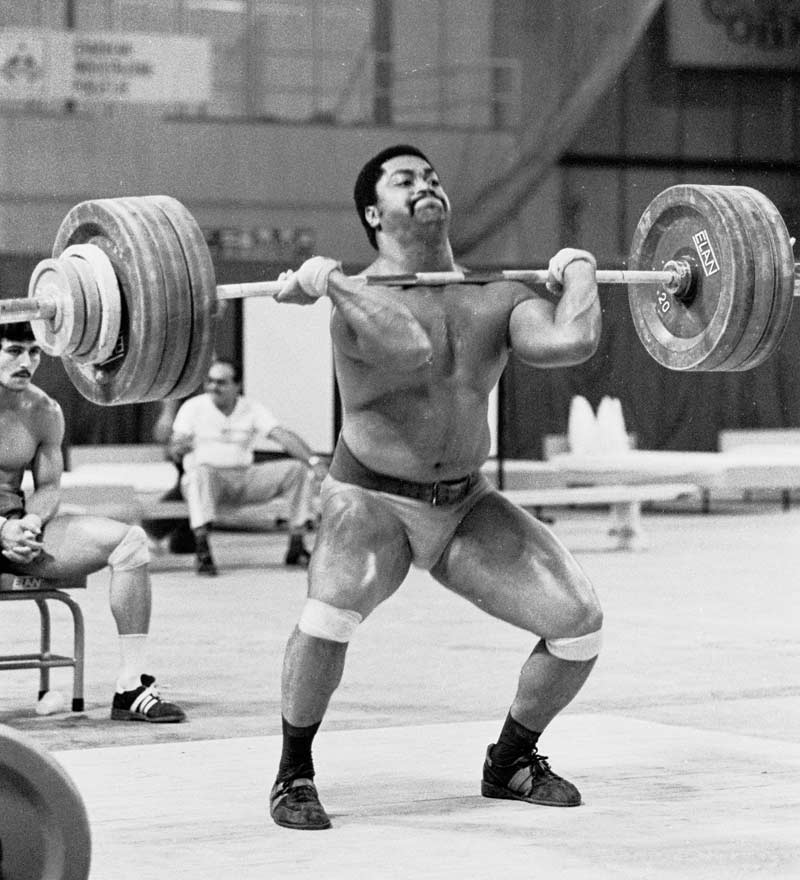

Header image by Bruce Klemens.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

Terry, T. “Historical Opinion: Karl Klein and the Squat.” (June 1984). Strength & Conditioning Journal. 6(3): 26-31.

Horschig, A., Sonthana, K., and Neff, T. (March 2017). The Squat Bible, pp. 97-100. Squat University LLC.

Verkhoshansky, Y. and Verkhoshansky, N. (2011). Special Strength Training Manual for Coaches, pp. 134-135, Verkhoshansky SSTM©

Hoffman, J., et al. (February 2009). “Comparison Between Different Off-Season Resistance Training Programs in Division III American College Football Players.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 23(1): 11-9.

Todd Lyons, Dynamic Fitness Equipment, Personal Communication, January 2019