What motivates me? The never-ending quest to provide the athletes under my watch with unique advantages in training that lead to official improvement in competition. “Unique” is a loaded word because I have never created anything brand-new. However, applying “older”/proven methods in an age of training ads on social media is becoming more and more unique.

What do we emphasize at Athletics Westchester?

- Sprints for mechanics and rhythm.

- Sprints for acceleration and max velocity.

- Olympic lifts.

- Plyometrics.

Meet results are the only true metric that says whether or not programming works. Track and field is a “show me the money” sport. Training groups with quality results, consistency, and improvement shows high-quality coaching. I research those coaches to find out what works for their athletes and practice what I find intriguing with my own. Two coaches whom I have studied are the late Tony Wells (Colorado Flyers) and his protege, Caryl Smith Gilbert (USC). Both put an incredible emphasis on power development and include the speed bound as an essential component of their training.

Over the last 3-4 years, I have sporadically programmed speed bounds with my athletes. Because of the “think time” that the COVID-19 shutdown provided me with, I decided to make a full commitment to speed bound programming. Throughout late summer and fall, we did speed bounds two times per week. Was it effective? Only official meet results could provide that answer.

Thankfully, the Armory Combine provided official competitive opportunities for our athletes. During the late fall/early winter, the Athletics Westchester training group consistently set personal bests in spite of challenging training locations due to COVID-19 and falling temperatures in the Northeast. What was the one constant? Speed bounds.

Putting the Speed into Bounds

Speed bounds are repetitive alternate leg ground contacts over a specified distance AFTER an acceleration. The acceleration is what puts the speed into these speed bounds AND what makes them challenging for the athlete to complete with proper timing and mechanics.

The acceleration is what puts the speed into these speed bounds AND what makes them challenging for the athlete to complete with proper timing and mechanics, says @AthWestchester. Share on XBefore your athletes speed bound, they must first master the bound without acceleration.

Bounding is like a field event. Without consistent coaching, video, and feedback, there is a tendency for these movements to become technically flawed. These technical flaws limit the effectiveness of an exercise with high risks that accompany the high reward.

I recommend coaches first prescribe short bounds without any run in. Athletes respond well to visualization. If you have someone who can effectively demonstrate, begin the training session with that athlete showing the movement as you coach the key points of emphasis. If you do not have an athlete who can effectively demonstrate, show example videos before the training session begins. Or, do both!

In addition, this is an opportunity for you as a coach to practice consistently delivering instructions and important feedback. Even with our most skilled athletes, I show them example videos prior to our bounding sessions and remind them of their why. Here is a great article by Rob Assise that features quality videos of short bounds.

Once they become skilled at the short bound, introduce speed bounds. We use two variations of the speed bound: straight leg and alternate leg.

Speed bounds are described as an acceleration over a given distance (10-30 meters) immediately followed by a bound (20-60 meters). To summarize Coach Smith Gilbert (USC) from the Complete Track and Field Masters Class last spring, speed bounds develop “elastic strength by training the athlete to get off the ground and get back on the ground without braking.” Translation: improved stiffness at ground contact.

These exercises have great carryover to the demands of maximum velocity because they train the body to overcome resistance at a high rate of speed. This is the advantage of the speed bound over plyometric movements without an acceleration. Other than pure sprinting, the speed bound is the closest exercise that applies significant horizontal force at high speeds. In addition, speed bounds require quality mechanics, coordination, and rhythm. These common buzzwords provide a summary of what we try to accomplish: handling and/or enhancing the demands of sprints, hurdles, and horizontal jumps in practice.

Speed bounds have great carryover to the demands of maximum velocity because they train the body to overcome resistance at a high rate of speed. Share on XIn my opinion, the straight leg speed bound is easier for athletes to learn and, therefore, the first we introduce.

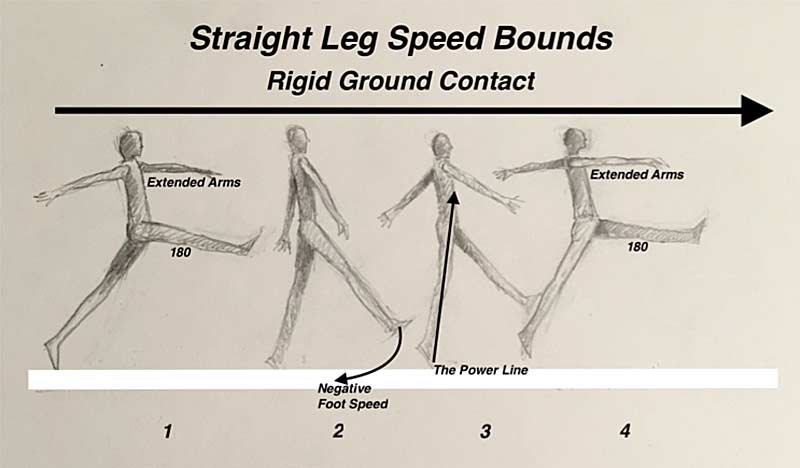

The Art of the Straight Leg Speed Bound

AFTER an acceleration of 10-30 meters:

- While keeping the legs straight (180 degrees or very close to it) and the foot dorsiflexed, continue the momentum established from the acceleration by rotating from the hips. We want the arms fully extended and long. This arm action improves the timing and coordination of the exercise by slowing the movement enough to prevent the athlete from “searching” for the ground too early, which usually results in the dreaded plantarflexion at contact.

- Emphasize horizontal power through “negative foot speed” and a rigid plant leg. Negative foot speed is the rate at which the foot moves backward as it strikes the running surface. This is a key skill that we evaluate with video after each rep. What we are looking for is not only a downward motion but a rapid backward motion through ground contact. Negative foot speed is what allows athletes to continue their bounding momentum for longer distances.

- With an emphasis on negative foot speed, the leg “pulling” downward should land at or close to 180 degrees of extension below the center of mass (COM). This rapid and rigid ground contact creates the “power line” that projects the COM forward through the hip extension of the swing leg. The emphasis should always be the downward force, which will naturally move the swing leg both horizontally and vertically. Athletes who emphasize the vertical motion of the swing leg tend to lose momentum and/or have a tendency for their upper body to lean excessively backward. To remind the athlete of the appropriate downward leg action, our cue is always “Pull, pull, pull.”

- In position 4, we move to the same position as number 1 with the arms and legs switched. This action is repeated over and over for the prescribed distance of the bound.

Here is a sample video of an Athletics Westchester athlete completing a straight leg speed bound of 40 meters after a 20-meter run in. His emphasis on downward force produces excellent negative foot speed and consistent rigid ground contacts that allow him to maintain momentum through the entire rep. My only suggestion would be for this athlete to complete the drill with longer/extended arms.

Video 1. An Athletics Westchester athlete completing a straight leg speed bound. My only suggestion would be for him to finish the drill with longer/extended arms.

Once the straight leg speed bound becomes efficient, we introduce the alternate leg speed bound.

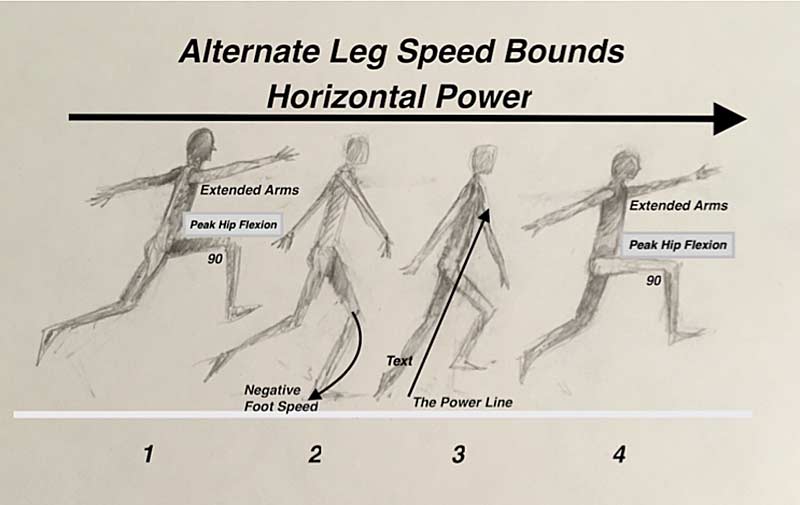

The Art of the Alternate Leg Speed Bound

AFTER an acceleration of 10-30 meters:

- With knee flexion at 90 degrees and the foot dorsiflexed, continue the momentum established by rotating from the hips. We keep the arms straight for the same reasons as for straight leg speed bounds.

- Again we see the importance of negative foot speed. I feel this is a greater challenge with the alternate leg version, as many athletes become impatient during flight and move their foot/shin well out in front of their knee. Once this happens, the timing, rhythm, and coordination get disrupted, and the athlete’s alternate leg bound becomes an ineffective hybrid without negative foot speed or rigid ground contact. Although the athlete is moving fast due to the acceleration, the rhythm of the drill must be methodical. This is a challenge that you and your athletes will have to work through.

- The power line is present. With the emphasis of downward force and negative foot speed, the foot should strike under the COM with a leg that approaches 180 degrees at contact. If the plant leg shows significant flexion in this portion of the movement, it is a sign that the athlete is contacting the ground in front of their COM. What should you emphasize to correct this? Negative foot speed. This is where video feedback is critical since these key positions are challenging to see in real time.

- For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. Quality downward force and negative foot speed combined with the stretch reflex of the swing leg allow for an effortless back side to front side recovery. We tell our athletes to simply “flick the shin” under the knee. This action is repeated over and over for the prescribed distance of the bound.

Here is a sample video of an Athletics Westchester athlete demonstrating an alternate leg speed bound of 50 meters from a 30-meter run in. His patience between each bound allows him to complete the rep with excellent coordination, timing, and rhythm. In addition, the downward force with negative foot speed produces consistent rigid ground contacts that allow him to maintain momentum through the entire rep.

Video 2. An Athletics Westchester athlete completing an alternate leg speed bound. He demonstrates excellent coordination, timing, and rhythm.

Apply the Speed Bound to Your Practice Plan

Now that the what and how have been explained, the inevitable volume question must be answered. Below are some recommendations of how our training group incorporates speed bounds. Simple summary: quality > quantity

1. Start short and gradually increase the distance for acceleration, as well as the distance of the bound, as the athlete improves.

- Beginner: 10-meter acceleration followed by a 20- to 30-meter bound for 4-5 repetitions.

- Intermediate: 20-meter acceleration followed by a 35- to 45-meter bound for 5-6 repetitions.

- Advanced: 30-meter acceleration followed by a 50- to 60-meter bound for 6-8 repetitions.

- All reps require as close to full recovery as possible. For us, that equals 3-5 minutes.

2. Our recommended surface area is turf or grass in order to limit the potential for injury to the foot, ankle, shin, and knees.

3. We speed bound 1-2 times a week during our preseason and once weekly during our early competitive season, and we eliminate the exercise as we prep for the championship portion of our season. Always provide at least two days between speed bound workouts to give the athletes enough time to recover.

4. Our speed bound workouts normally take place on the same day we emphasize acceleration. Since we ask our athletes to accelerate as part of their bounds, emphasizing this skill before speed bounds creates a “part, part, whole” transition from the beginning to end of practice.

Since we ask our athletes to accelerate as part of their bounds, emphasizing acceleration before speed bounds creates a ‘part, part, whole’ transition from the beginning to end of practice, says @AthWestchester. Share on XHow Do We Know Speed Bounds Work?

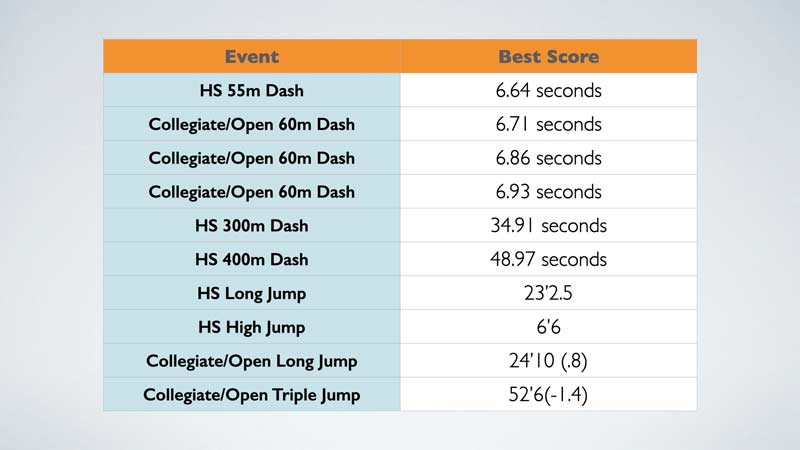

Although we do not own a contact grid, we can still measure improvements in acceleration and max velocity in practice to evaluate the effectiveness of speed bounds. However, the best indicator is official competition. Meet results are truly the only metric that says whether or not programming works. Our training group was fortunate to produce some quality official meet results even though training options were limited due to COVID-19 restrictions and some cold temperatures in New York.

Every performance listed below is a personal best for each athlete, and I feel that the speed bound played a significant role.

Rely on Proven Methods

Speed bounds take time and patience to master. They are worth the investment because they will help your athletes become more powerful, mechanically sound, and resilient. In addition, they will help you become a better instructor because they demand your ability to clearly communicate, provide feedback, and troubleshoot.

Meet results are truly the only metric that says whether or not programming works. Share on XAll of these challenges are opportunities to provide athletes with exercises that are proven methods by master sprint coaches of the past and present. The “art of the speed bound” is one of those proven methods. Learning, teaching, and applying the speed bound is the “art of coaching.”

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF