I’ve written before about the compressed triphasic system I use with fighters or any athlete peaking for singular events. This is an idiosyncratic approach to applying the triphasic method to MMA fighters; hopefully there were lessons others could glean from marrying an intensive method to an athlete, which leads to a lot of complexity for strength and conditioning coaches. But the fundamental lesson is how we can achieve our desired outcomes in an environment that is chaotic and ever-changing.

The fundamental lesson is how we can achieve our desired outcomes in an environment that is chaotic and ever-changing, says @WSWayland. Share on XThe limits of block sequence and linear periodization systems mean that for prolonged periods of the training year, we cannot utilize highly qualitative training instances to improve specific qualities and that often a mixed modalities approach means some qualities can end up being undertrained. The triphasic system’s rigidity bumped up against my reality of needing condensed models, like with MMA or grappling, versus flexible models accounting for higher degrees of variability.

Most of what we are taught in strength and conditioning is a series of small-world models that are sequentially lined up to build what looks like a coherent long-term strategy. In Mladen Jovanovic’s book, he suggests “We must be cautious in applying small-world, scientific, optimal ‘truths’ to the real world of athlete development.”

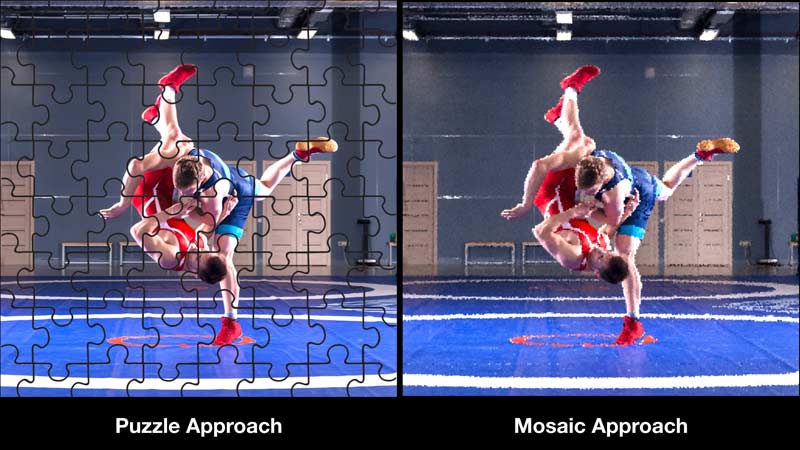

Puzzles vs. Mosaics

Good strength and conditioning practice is a gestalt of sorts, with the whole being greater than the sum of its parts. Much of the theory is based on lining those parts up to achieve a desired training effect or optimal athlete state. Top-down strength and conditioning strategies such as block linear-style periodization are often like jigsaw puzzles, with neatly designed interlocking pieces. They’re complex, it takes time to put the pieces together, and if you lose one piece, it ruins the puzzle. Or to take this analogy to a Jenga puzzle, take away enough pieces and it falls down, or it is easy to knock over when external forces act upon it. Degrees of variability are what cause issues for top-down or small-world thinking.

One solution I have grown fond of is to take more of a mosaic strategy approach than a puzzle one. Mosaic warfare, from which the strategic idea borrows its name, is a multi-domain, combined arms warfare conducted in parallel over wide areas, at machine speeds that cognitively overwhelm a linear adversary. The basic idea is more flexible and adaptable than monolithic systems and rigid architectures. If a small part is taken out by the opposition, it does not render the whole useless. Mosaic FOREX trading, for instance, is a diversification strategy that traders use to spread risk.

When a puzzle loses a piece, it’s clear that a piece is missing, and the replacement needs to be an exact copy of that specific size, shape, and color. A mosaic strategic approach uses a palette of broken tiles of different shapes and sizes to build something ordered. If you break or lose a piece, there are many like it that you can use as a replacement to complete the picture. Up close—let’s say a few inches away—a mosaic looks like a mess, but as you draw out, it builds a large, clear image.

To a strength and conditioning coach or a sports coach, those broken or missing pieces could appear as an acute injury affecting this week’s training plan, a lack of equipment, a flat battery on a piece of technology, a viral pandemic, or a losing streak for an athlete, causing an upheaval in circumstance. Mosaic strategy asks what we can use to fill that hole that may not be exactly the same color, size, and shape as the original piece, but at a distance match the perceived whole. The opportunity also exists to piece together new effects on the fly.

The key point to this is that different capabilities from different domains operate on different time scales. Strength and conditioning coaches get a unique insight into athlete readiness—psychology that the sports coach, nutritionist, physiotherapist, or sports med (and vice versa) might all miss, as these different domains operate on different time scales and information sets.

Making the Most of the Unknown

The unknowns you will encounter obviously depend on the types of athletes you work with. If you work in a conventional team sport, you probably have a regular team calendar and regular access to team training facilities, so you can plan for athletes around regular season games, athlete readiness, and training residuals.

In my own situation, an athlete will sometimes come to a training session without my having ever met them. Not knowing their capabilities, this requires a bottom-up approach that satisfies the principles of training rather than any long-term speculative modeling or planning. Barbell sport athletes, for instance, have the most rigidity in their preparation, usually working in the same training space while having minimal variables to deal with. It is interesting that the athletes with the fewest variables and most rigid and least plastic training approaches should inform the orthodox training approach the rest of us are encouraged to take.

It is interesting that the athletes with the fewest variables and most rigid training approaches should inform the orthodox training approach the rest of us are encouraged to take. Share on XNonuniform waving between rigidity (our whole mosaic) and plasticity (the ability to change pieces) in our approach is key to making this work. Trying to plan this type of training from the top down doesn’t work; you just have to plan accordingly so that the training dose occurs often enough to maintain training effect. You need to use collaboration with the athlete along with your best judgment to decide when the time is right—what is known as “sprint and release” programming.

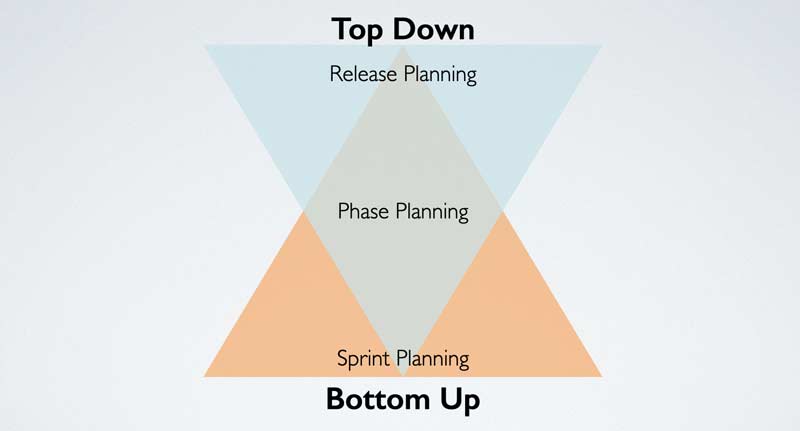

Sprint and release programming is an approach I have borrowed from Mladen Jovanovic. An iterative model, as Mladen explains, consists of “three time-frames: release, phase and sprint, each having a planning component, development component, and review & retrospective component (which are needed to update the knowledge for the next iteration). Why did I choose different names? To act smart? First of all, different frameworks demand different language. Second of all, planning in this framework, as opposed [to] contemporary planning strategies, is iterative rather than detailed up-front. Taking all of that into account, it is essential to use the terminology which will better represent the iterative planning approach and differentiate it from more common planning strategies as well.”

Mladen has used terminology largely synonymous with Silicon Valley tech start-ups. The process, however, is a simple one: Release a product, reflect on it, release another, rinse, and repeat. Rather than plan out a detailed process from top to bottom, have a release strategy guided by principle, a phase strategy guided by refinement, and a sprint strategy guided by pragmatism. Release, in this case, is my mosaic, and sprints are the interchangeable pieces.

Well, what does this have to do with triphasic concepts or microdosing? Below I will explain how I’ve taken this conceptual framework and applied it to my approach with loading, moving from macro planning to micro day-to-day workouts.

Iterative Triphasic, Microdosing, and Training Half-Life

The strategy with the release, phase, sprint approach lies in iterative dosing of the right individual qualities expressed across sprints. It’s not as structured as year-round planning, and not as frequent as the microdosed approach that inspired this thinking.

The idea is that if we microdose the right high-return individual qualities, we can use them to build upon a sustained training effect for the subsequent training phases and sprints. Derek M. Hansen borrowed this nomenclature from the world of doping, and I’m paraphrasing it: the strategic use of exogenous testosterone by athletes to sustain elevated testosterone levels just under the allowable testosterone-to-epitestosterone ratio of 4 to 1. So, to keep this ratio up, the athletes would regularly microdose small amounts to pass testing.

The idea is that if we microdose the right high-return individual qualities, we can use them to build upon a sustained training effect for the subsequent training phases and sprints. Share on XProper use of a microdosing program means we can kick the can of training qualities a bit further down the road and employ proper residuals. This is the beauty of microdosing with occasional supramaximal or submaximal training.

Do not get too hung up on semantics here, as it is not really microdosing in the true sense. I started using the phrase “iterative dosing,” which then became iterative triphasic (IT). What sort of training am I approaching in each sprint/phase iteration? Well, in this case, making the most of supramaximal effects. Does it have to be triphasic? No. Does it have to be supramaximal? No. Use whatever intensive iteration of your own model you want. I am just laying out mine, based off a model I’ve used extensively.

Why would I want to dose heavy eccentrics or supramaximal work in season?

There are several acute physiological changes that supramaximal training forces on the body, which is the biggest justification for this method and the same justification for trying to fit in intensive strategy in season. I talk about this in my squat article for SimpliFaster.

“Reconciling these benefits (of heavy strength training) with an athlete who may have a busy schedule and high training volumes can be tricky for coaches. We can, however, manipulate things a little to provide intensity, keep volumes appropriate, and make changes to minimize technical aberrations. The key is to apply stress in a fashion that yields benefits and mitigates drawbacks. If this has to bend orthodoxy slightly, then so be it. We can provide this in the form of derivatives, clever rep schemes, and load manipulation.”

Having a smart iterative plan that allows for the implementation of intensive methods when needed would be an addition to derivatives, rep schemes, and load manipulation, but you need to be able to justify it. I’m not shy about trying to integrate intensive methods and heavy barbell work in season and, in general, as part of my long-term training principle.

The physiological and neurological response from supramaximal training is enormous. It kicks tissue remodeling and neural changes into overdrive. We see improvements in maximal muscle recruitment and maximal fast twitch recruitment and even the potential for very controversial hyperplasia.

Why would I want to microdose heavy eccentrics in season?

The key points are these:

- Eccentric training can improve muscle mechanical function to a greater extent than other modalities.

- Novel muscle-tendon unit adaptations associated with a faster (i.e., explosive) phenotype have been reported.

- Eccentric training may be especially beneficial in enhancing strength, power, and speed performance.

- Increased stiffness of titin isoforms.

- Robustness.

I’ve said before that, ostensibly, an athlete could derive an enormous amount of structural and strength benefit from just eccentric-focused supramaximal training, but muscle action is a three-part process.

Why would I want to microdose heavy isometrics in season?

- Greater tissue adaptation.

- Muscle fibers are fired and re-fired throughout the duration of the repetition to the greatest extent with supramaximal loads, even though no movement occurs.

- Maximizes the free energy that is transferred throughout every dynamic muscle contraction and the SSC.

- Second order benefits, like peripheral BP and bracing.

- Robustness.

In both of these methods, the key effect is that optionality of robustness. By taking the time to insert these phases into training, their benefits help form the foundation for future training cycles and help me get the most out of our freer form of training design. Back to our earlier analogy: I like to think of robustness as the bonding agent that holds our mosaic together.

The type of iterative intervention we use matters because the repeat bout effect of supramaximal training, for instance, can be effective at yielding long-term protective effects better than prophylactics. As the old adage goes, a little intensive short-term suffering is preferable to prolonged low-level suffering.

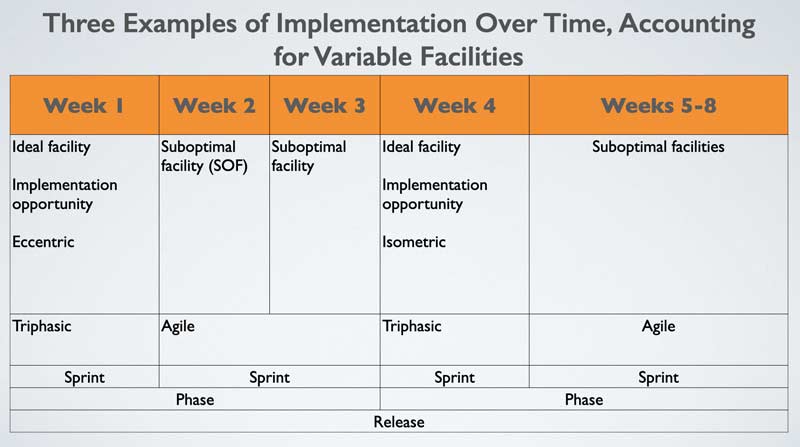

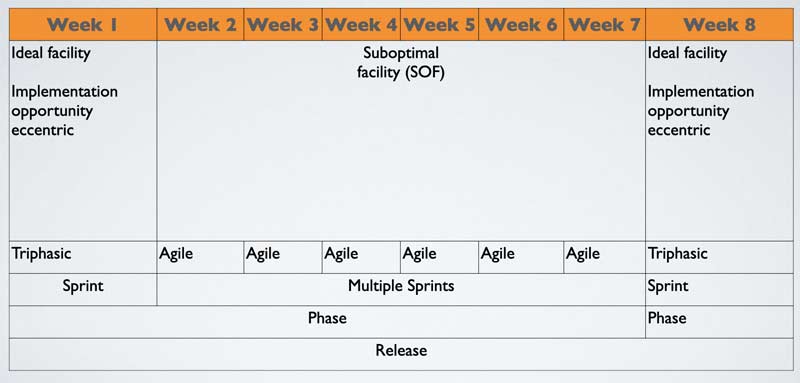

This type of microdosing is not the same as, say, the sprint microdosing set out by Hansen, which would have near-daily frequency. Keep in mind that with supramaximal work you might only do this 1-2 times a year as part of a conventional 16- to 20-week intensive off-season program. What I suggest is a frequent dosing of 4-, 8-, and 10-week intervals. Compared to just, for instance, once a year, these are still a lot more dosages.

Why dose training this way? Supramaximal residuals are long and punctuated often enough throughout a trainer year as various phases and iterations can keep conferring benefits for a prolonged period. The point is that the benefits of this type of rigid structured training are numerous, so we have to insert it into our planning somewhere.

The point is that the benefits of this type of rigid structured training are numerous, so we have to insert it into our planning somewhere, says @WSWayland. Share on XThe compressed method means we can aim for 4-, 2-, or even 1-week blocks when the opportunity arises. For those forced into 2-week training windows, you can look at choosing between eccentrics or isometric stimulus depending on what the athlete needs to work on. You can employ a lower-quality mixed approach that merges both eccentrics and isometrics into the same working rep (eccentric iso’s). This comes with the drawback of being energetically demanding and, as a result, it will be much less qualitative than training eccentrics or isometrics as singular target qualities. This, in turn, gives us time to employ a submaximal approach during or between dose weeks.

The stronger the athlete, the more variability we can get away with and less residual loss we will see. I will set out how we go from phase to sprint planning, down to the individual workouts, to give you a sense of what I am getting at. I abhor when coaches lay out fancy strategic models without showing how they actually execute them from whiteboard to rack. To quote Nassim Taleb: “It’s easier to macro bullshit than it is to micro bullshit.”

Ideal Facility Week

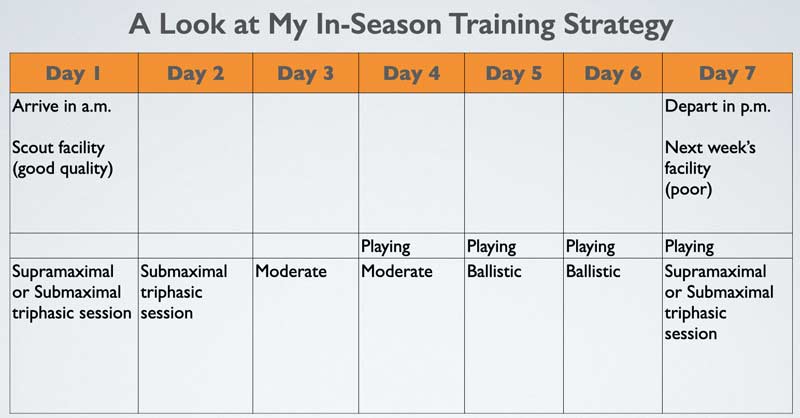

For the extremely time-poor, when implementing in season is impractical, try to fit two doses within the week. I sometimes do this to give me and the athlete more time before the next time we need to dose. I have used the strategy below in golf, but it could also work well in baseball.

The above situation dictates our strategy on the day we scout our facility. A lot of my struggle with the triphasic system or any block system is its first contact with reality. The bottom-up approach and agile decision-making work well for me with athletes who travel; however, if you want to apply it to athletes who play regular season games and have a known base of operation, you can take whichever approach suits. Conversely, you could use the same approach if an athlete is at a “home base” facility before traveling off again.

Below is a regular training week I’ve implemented in season for an athlete who preferred an upper low split across a seven-day week.

The Training Week and Within Week Variability and Using Data to Inform OODA Loops

“Variable weeks” speak not only to equipment variability, which is a very possible scenario for me with athletes, but also variability in readiness. This increasing mix of subjective and objective measures is starting to creep into the training environment, empowering the athlete to shift the ever-changing pieces of their physical state. This could be HRV scores, subjective questionnaires, dialogue, or velocity-based measures. This where interoperability—for instance, information sharing—is a super important aspect of the mosaic approach, as at its heart, athlete preparation is not just strength and conditioning but an interdisciplinary practice. A crucial element in this thinking is the “speed” of adaptability to a changing situation, not just paying lip service to the concept.

An increasing mix of subjective & objective measures is starting to creep into the training environment, empowering the athlete to shift the ever-changing pieces of their physical state. Share on XWe have more data solutions than ever, which means we can adapt to variable circumstances but also track solutions. We feed this information into an OODA loop, which stands for observe–orient–decide–act. This is a type of decision cycle developed by military strategist and United States Air Force Colonel John Boyd that is also used in business, litigation, and law enforcement.

A lot of coaches may perform elements of this as part of their normal practice. I was first introduced to an OODA loop as an agility concept for athletes; an implicit strategy for not actually being the most agile, but having the ability to disrupt an opponent’s OODA loop, using fake movement, etc. I use OODA loops as part of my process of choosing how to approach a sprint based on the data I have available.

“A key part of this is distinguishing the relevant from the insignificant, and this will be based upon a number of factors including experience. This ability to interpret information is critical as all the information in the world is of no use unless it can be interpreted. The Decision phase then involves deciding on a course of action and selecting one path, and the Action phase will then carry out this decision. Performance is therefore dependent on the effective development and execution of each phase, and a weakness in any will reveal itself as a limit to performance.” (from Performance Management That Makes a Difference: An Evidence-Based Approach)

Having a decision-making framework of some sort is crucial because there is no excuse for winging it. The busy work coach, the spontaneous exercise inventor, and the drill-them-’til- they’re-dead coach are the sorts who put deciding and acting above the crucial skills of observing and orienting.

Sprint Planning

Individual session design should be a straightforward affair using an OODA loop.

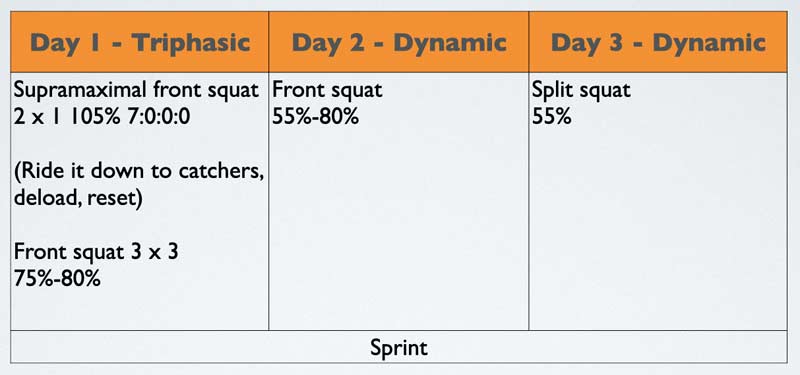

Session design for my in-season (or offseason) planned triphasic sessions is fairly straightforward: Rather than applying triphasic means to as many exercises as is appropriate, we apply the triphasic stimulus to the movement that will get us the most return, second order benefit, and residual. This is usually the movement that starts the session. Part of the selection is informed by athlete preference and equipment availability.

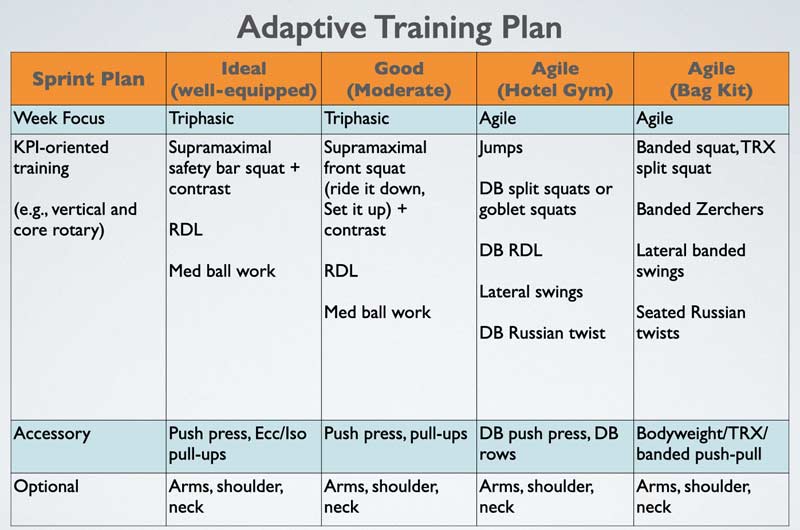

Rather than applying triphasic means to as many exercises as is appropriate, we apply the triphasic stimulus to the movement that will get us the most return, second order benefit, and residual. Share on XMicro planning for your triphasic days can also require adaptability. Because many athletes I work with now have variable training environments, my triphasic approach must account for that variability. If they have safety bars or trap bars, we can employ a near (90%+) or semi supramaximal approach within a training week when the opportunity presents itself— it is a training feast-and-famine approach. The beauty is that the more you and the athlete do this, the easier it becomes.

The session planning or decision-making itself is where the craftsmanship qualities of a coach get to shine. The aim should be brilliance in subtlety, objective measures informing coach decision-making—basic exercises with tweaks in joint angles, force velocity relationship, and TUT that provide just enough specificity for the needs of the individual but also are able to adapt to variable situations.

Programs should be aesthetic. I am a big believer that if it looks good, it is good, and most good coaches can intuit this just by looking at a program and its intent. Programs should be minimal or at least meet the idea of another Mladen principle I like: minimal viable performance (MVP)—is it enough to achieve our immediate aims? It should have enough context and be easy to understand, it should match the thrust of intent in order to fit even roughly into our overall picture. To bring it back to my earlier metaphor, these are elements that make the mosaic.

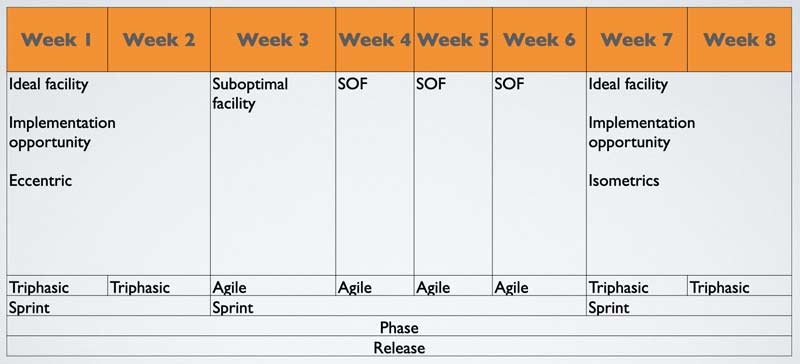

Here is an example of an ideal week that allows us to employ intensive dosing.

We can boil this down further into an ideal scenario versus non-ideal scenario for our agile weeks. I outlined a little of the plan A, B, C thinking in my tips for golfers post. Below is a suggestion for approaching that day 1 scenario based on whether you’ve had to adapt to an optimal or suboptimal scenario using an OODA loop.

This where we move away from our structured triphasic sprints; we have to implement what is, in effect, a form of adaptive planning based on circumstance. This is a commonality for athletes based in touring sports like golf, tennis, motorsport, etc. Either way, training IS happening.

Observe the training facility or lack thereof— what does it have: barbells, racks, trap bar, med balls, etc.? Orient based on what the athlete needs. Strength? Ballistics? Hypertrophy? Decide by merging the last two together. How do I use this to embrace the challenges I am facing today? Then finally act and execute the training plan based on these.

Could I Dose Intensive Work More Regularly?

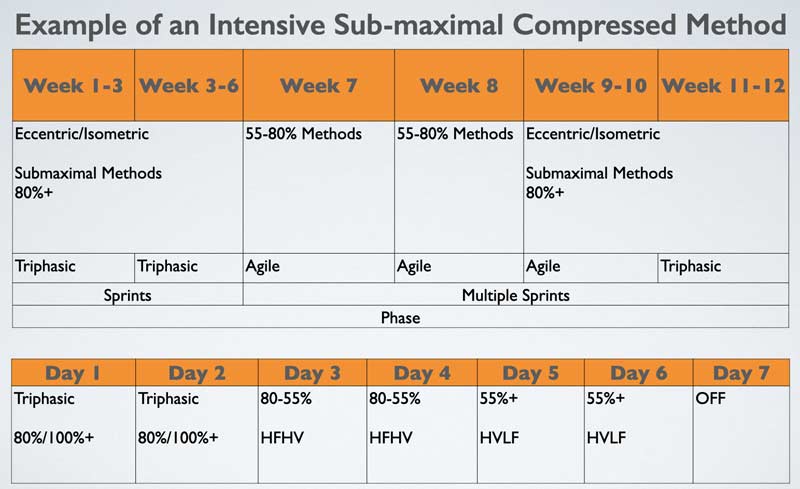

Using supramaximal eccentric or isometric means that dose volume and frequency would be lower, whereas the submaximal method would have a less pronounced and prolonged effect but could be based more frequently. A lot of frequency is dictated by training age, athlete competency, and also buy-in to the approach. So, an intensive submaximal compressed method would look like this (repeat throughout the year):

While I am trying to articulate a very fluid approach, I have found that the more very experienced coaches I talk to, the more they seem to operate in this fashion, usually as an expression of implicit knowledge. The other big caveat to this is that, at least initially, most athletes may need to start their training in a very rigid sense. Then, as training age accumulates, it gives them the solid foundation upon which abstraction can be built.

The key to this approach being successful is using a pragmatic decision-making process like an OODA loop, and it becoming a long-term iterative process of refinement across repeat applications of releases and phases. I am not naive enough to believe this approach will work for everyone, but it is an approach that has recently served my own idiosyncratic circumstances very well.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Jeffries, I. “Agility training for team sports – running the OODA loop.” Professional Strength & Conditioning. 2016;42:15-21.

Munger, C.N., Archer, D.C., Leyva, W.D., et al. “Acute effects of eccentric overload on concentric squat performance.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2017;31(5):1192-1197.

Wirth, K., Keiner, M., Szilvas, E., Hartmann, H., Sander, A., Wirth. “Effects of eccentric strength training on different maximal strength and speed-strength parameters of the lower extremity.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2015;29(7):1837-1845.