My advocacy of triphasic training developed by Cal Dietz and expanded upon by Matt Van Dyke is well known. As a proponent of the method’s principles, I’m endlessly trying to find ways to amplify its positives while mitigating the negatives—as would any good coach when applying any system or principles.

Tackling the sport of MMA is challenging and not a task many people would think would marry well with intensive work like eccentrics. Time limitations, muddied stimuli, and the need for a wellspring of differing qualities can make the MMA athlete an athletic Gordian knot of sorts. MMA fighters are athletes at a crossroads of competing, middling demands. Just giving athletes lots of variable stimuli, often in the guise of well-intentioned sport-specific training and energy systems work, adds to the confusion. This is a rapid way to achieve very little but look good doing it.

I concluded a long time ago that, to move the needle, we need to punctuate regular training with intensive stimuli. Imposing intensive physiological demands, especially once momentum builds, can be sustained by athletes cyclically, even those with cloudy schedules such as MMA fighters. Common thinking believes this imposition will lead to ruin. Bob Alejo wrote about how intensive stimulus can build robustness and injury tolerance, even when athletes are under duress due to their competition schedule. Like Bob, I abhor the idea of maintenance.

I liken the MMA training cycle to being “in-season” almost constantly, especially at low to mid-tier levels of the sport where, let’s be honest, the bulk of athletes operate (not everyone is in the UFC). Taking examples from others sports, we know intensive in-season work, once habituated, builds robust athletes. After I started applying compressed blocks—punctuated 3 to 5 times throughout a year, usually between 12 to 8 or 6 weeks out for MMA fighters—we saw sustained strength and power levels throughout training camps during peaking thanks to the incredible residuals this approach yields.

While this article focuses on my idiosyncratic approach to applying the method to MMA fighters, hopefully there are lessons others can glean from marrying an intensive method to an athlete, which poses the most issues for strength and conditioning coaches.

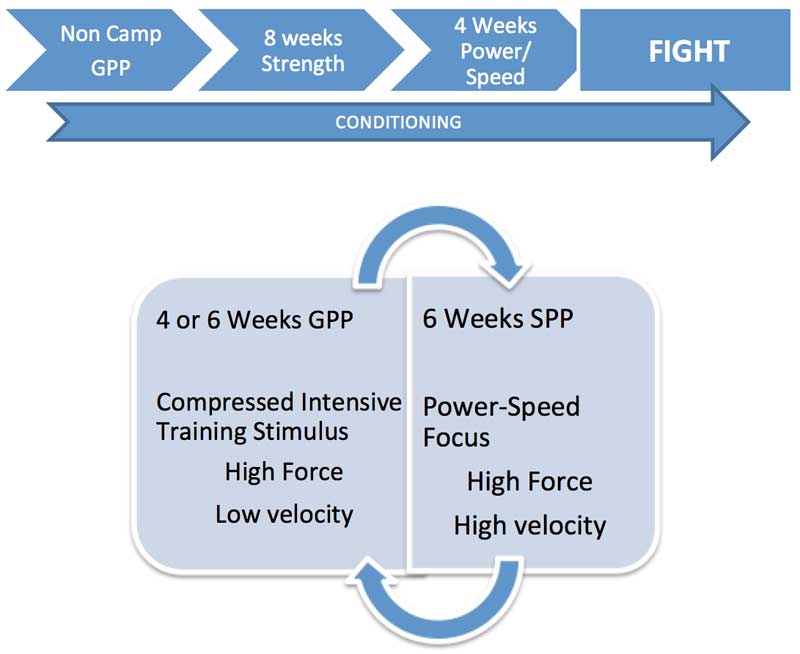

The traditional MMA model is predicated on an 8- or sometimes 12-week fight camp. The camp is a period of intensification: high volume sport loads and voluminous conditioning approached with a focus on game- and round-based conditioning. This is often combined with low caloric intake to make weight and is preceded by a variable GPP program, which can be long or short (and the not-knowing can make life hard for strength coaches).

GPP usually consists of aerobic base building, maximal strength work, and very general technical training or brushing up on perceived technical shortcomings from the fighter’s last bout. Often, GPP is dropped immediately when a date is announced. This can make it hard for fighters to do intensive strength work consistently, especially when athletes strive to stay in fight shape for prolonged periods or take long breaks post-fight. By focusing on a cyclical back and forth between intensive and non-intensive sport-focused cycles, we can keep athletes primed without wearing them down.

Traditional 8-Week Out Model

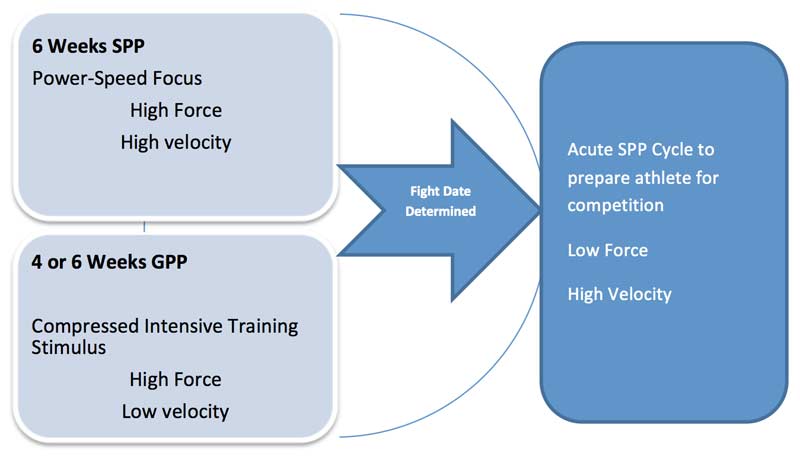

When a fight is announced, we move to an acute SPP block to prepare. How quickly we break off the cyclical model is determined by the length of time the athlete has before their fight.

For instance, a 12- to 16-week time frame allows the athlete to stay on the cyclical model to finish out the accumulation of their current training stimulus. Eight weeks or less, however, requires the athlete to break off the cyclical approach far sooner.

There should be no problem jumping straight from compressed intensive training to high-velocity peaking—in fact we may see some serious potentiation from such an approach. One caveat that I’ll add is that an intensive GPP block for athletes with a low training age is conventional submaximal lifting, which I’m happy with up until the athlete develops a competency.

Application of Supramaximal Training and Training Compression

Compressed intensive training is a period in which we apply the greatest stimulus to accumulate the desired response in the shortest time possible—this is where we apply supramaximal training. Supramaximal training is one of the approaches that excites muscular physiologists, as it leads to rapid adaptations and a reduced need for the repeat exposures we get from the same contraction focus at submaximal loads. Time, as a commodity, is always in short supply.

The question I often get asked is why apply supramaximal training at all when submaximal loads do a perfectly good job. I hear the clichéd statement in strength and conditioning about “all roads leading to Rome”—to me, this is relativistic tosh. Isn’t the best road the one that gets us there the fastest without the wheels falling off?

Very high-intensity, low-frequency training seems counter-intuitive for the coach who has a maintenance mindset. I’m not in the business of babysitting athletes: opportunities are available to add powerful stimuli when timed right. Supramaximal training is nothing new; it’s been a staple of athletes with long off-seasons and massive strength requirements for some time. I recall seeing early YouTube videos of suffering bobsledders with three spotters performing supramaximal back squats with 120% of their max for 10-second durations, and thinking most athletes could tolerate such a load.

MMA athletes need to be very strong, according to UFC Performance Institute performance director Duncan French at the recent UKSCA conference (I’m paraphrasing): Striking occurs in 200ms or less. Ninety percent of the variability in RFD can be accounted for by maximal strength. Given this primacy of strength, we have a slew of training options available to us—but “all roads lead to Rome, right?” I argue, again, don’t we want the fastest route? I’ll take the one that gives us the greatest depth of strength qualities trained, not just concentric-focused number-chasing.

Supramaximal Eccentrics

Eccentric muscle and neural action are enormously load-tolerant and physiologically different from their isometric and concentric counterparts. This is due to differing motor unit recruitment during muscle lengthening compared to muscle shortening. During eccentric movements, the motor pool is less activated, leading to the activation of fewer muscle fibers.

To quote Matt Van Dyke, “The fact that fewer motor units are activated means there are fewer myosin head attachment sites during this eccentric movement phase. These fewer myosin-actin attachment sites lead to increased stress on those filament attachment sites that are being used.”

Eccentric movements cause both muscle fibers and tendons to absorb high amounts of force, as the muscle resists lengthening under load. Carl Valle explored the value of eccentric training in an earlier article, which offered exercises that are rather targeted but make for great introductory eccentric application. We can, however, amplify all the positives using supramaximal loads and systemic full body stress, which means the stress on each myosin-actin structure is increased to an even greater extent than with ordinary submaximal eccentrics—basically, all the benefits of eccentric training turned up to 11.

A 2010 study suggested: “The enhanced eccentric load apparently led to a subtly faster gene expression pattern and induced a shift towards a faster muscle phenotype plus associated adaptations that make a muscle better suited for fast, explosive movements.” The training led to significantly increased height in a squat jump test versus conventional training. This was accompanied by significant increases in IIX fiber CSA.

In Jonathan Mike’s great NSCA classic, he mentioned that “In addition, the energy cost of eccentric exercise is comparably low, despite the high muscle force being generated. This makes eccentrics an appealing strategy for those wishing to gain additional strength and hypertrophy because of the fact that more volume can be performed without excessive fatigue.” The lack of excessive fatigue is part of the reason I’ve forged ahead so keenly with applying this type of training, especially in a population that has to deal with as much fatigue as MMA athletes.

The neural hangover from #supramaximal eccentrics is less than I anticipated, says @WSWayland. Share on XFor those who try the method, yes acutely supramaximal eccentrics are fatiguing, but I’ve found the neural hangover to be less than anticipated. The primary drawback is managing DOMS. In the same NSCA article, Mike also mentioned: “Research focusing on the effects of overload training (100–120% 1RM) during the eccentric phase of a movement has routinely demonstrated a greater ability to develop maximal strength. Research by Doan et al. reported that applying a supramaximal load (105% of 1RM) on the eccentric phase of the lift elicited increases in 1RM concentric strength by 5–15 lbs.”

Supramaximal Isometrics

Supramaximal isometrics are the second act of the supramaximal method. Ostensibly, an athlete could derive an enormous amount from just eccentric focused supramaximal training, but muscle action is a three-part process.

To quote another Matt Van Dyke article, “By training isometrically in a supramaximal fashion, greater tissue adaptation is realized within the muscle. This adaptation occurs as muscle fibers are fired and re-fired throughout the duration of the repetition to the greatest extent with supramaximal loads, even though no movement is occurring. The adaptations occurring within the tissue through this training maximizes the free-energy that is transferred throughout every dynamic muscle contraction and the SSC.”

Supramaximal isometrics force an athlete into a hard-braced position, no less grueling than its eccentric counterpart, but the feel is different. We’ve noticed that some athletes prefer isometrics to eccentrics, especially those athletes with a grappling base, as sustained isometrics are a constituent element of their sports. According to Yessis,“The isometric contraction is less intense than the eccentric, but up to 20% greater than the concentric and plays an important role for developing greater stability for better execution of strength exercises.”

The notion that isometrics are only any good for the joint angle trained is an outmoded one. We’re realizing that isometrics have a systemic effect, including changes in neural drive and cardiopulmonary effects due to the immense pressure placed on the system.

The outsized stressor of #SupramaximalTraining causes an outsized rebound of positive qualities, says @WSWayland. Share on XTraining compression is the yielding of favorable adaptations in a shorter time frame than would be considered “normal.” The outsized stressor supramaximal training brings causes an outsized rebound of favorable qualities. After single doses, I’ve seen improvements in jump values between sessions, possibly due to latent potentiation. Obviously, stretching any adaptive window beyond its limits will cause a breakdown an athlete can’t recover from—this is why subsequent supramaximal training exposures are short, intense, and limited.

As a population, MMA fighters generally handle high volumes of middling intensity, and the wear and tear of these athletes under these volumes mean that strength training often orients around exercises in under-loaded novelty. The idea is strength and conditioning, not stuff and conditioning. We achieve strength by making the strength training a short, but sharp, stimulus during which we induce residuals that carry the athlete through SPP phases and up until a fight. The change in thinking means having the bravery to get stuck into the application of what outwardly is the most intensive method available as coaches.

Application

Generally, load tolerances with supramaximal eccentrics are idiosyncratic to some extent, but they have the potential to be at maximum 140%-160% of an athlete’s given maximum. This 1RMECC is difficult to ascertain, but there have been theoretical maximums of 160%+. For the sake of safety, keep athletes below 120%. While higher tolerances are achievable, there does come a time when we have to draw a line under what we can achieve safely.

The Conventional Supramaximal Method

Conventional sequence systems for supramaximal training are intended to be sequenced over longer periods to allow for adequate adaptation and recovery.

| Weeks 1-2 | Week 3 | Week 4-5 | Week 6 | Weeks 7-8 | Week 9+ | ||||||

| Eccentric 105-120% | De-load | Isometric 105-120% | De-load | Concentric 80%+ | Concentric 55-80% | ||||||

| Day 1 115-120% |

Day 2 90% | Day 3 105-110% |

Day 1 115-120% |

Day 2 90% | Day 3 105-110% |

Day 1 75-80% |

Day 2 85-90% |

Day 1 55-62.5% |

Day 2 65-72.5% |

||

When applying supramaximal blocks for 1-2 weeks, you perform eccentric lifts at 120%-110% of your max on Monday, normal 90-97% lifts on Wednesday, and 110%-105% eccentric lifts on Friday. De-load for one week and perform the same with isometric squats. Then perform another de-load. This is followed by two concentric weeks at 80/90/72 per normal triphasic training undulation. The de-loads are intended to give soft tissue a recovery opportunity, as supramaximal eccentrics and isometrics induce very high levels of DOMS.

The Compressed Supramaximal Method

Because of the unpredictable nature of the MMA fighters’ schedule, we use a compressed sequence. In effect, we remove the de-load weeks and jump straight to a high-force high-velocity training block. Because we only have two lifting days and we removed the heavier concentric work, we can afford to take out the de-load sessions.

I’ve used this compressed approach with UFC fighters and high-level amateurs alike, and have great returns in improved MTP and jump numbers, as well as numbers in their conventional lifts.

| Weeks 1-2 | Weeks 3-4 | Weeks 5-6 | |||

| Eccentric 105-120% | Isometric 105-120% | Concentric 55-80% | |||

| Day 1 115-120% |

Day 2 105-110% |

Day 1 115-120% |

Day 2 105-110% |

Day 1 55-62.5% |

Day 2 65-72.5% |

Exercise Choices

While I like keeping the stimulus consistent, you could alternate during the two days between a bilateral and a unilateral option. Systemic stress still being total, and movements being somewhat similar, we should yield similar results. Note that all the movements are squat-focused over any deadlift/hinge pattern: overloaded hinge is difficult in all but submaximal eccentrics and flywheel-type work. The sheer on the lumbar would make any purer supramaximal hinge movement potentially very, very risky.

We're not building powerlifters so the exercise is less important than the stimulus, says @WSWayland. Share on XI’m occasionally asked, “Why not use conventional back squat?” While this is a potential option, it comes with a number of risks: intense T-spine discomfort, the need for three spotters, and risk of T-spine collapse, which can cause the athlete to fall forward. We’re not building powerlifters here, so the actual exercise chosen is less important than the stimulus we try to apply.

Trap Bar Supramaximal Lowering

Trap bar lowering is probably the simplest method of delivering supramaximal efforts with minimal fuss in most gyms, considering that a squat safety bar is not often available. Most athletes are familiar with the trap bar deadlift, and getting them to buy into this variation is simple. The caveat, however, is that you need two spotters to help initiate the exercise, and then the athlete is responsible for lowering the bar to the floor.

The movement requires the athlete to stay tall and minimize any forward lean, keeping the pattern squat dominant rather than hinge dominant to avoid stressing low-tolerance structures. The athlete must make sure they center their grip, or use straps, as any tipping of the bar with supramaximal loads will be difficult to recover.

Video 1. The athlete needs to move in a squat pattern, rather than a hinge, and center their grip or use straps to prevent tipping.

Trap Bar Supramaximal Pause

Much like the trap bar lowering, the supramaximal movement with a pause works well as a low-entry exercise.

Video 2. After two spotters lift the bar into position, the athlete drops as quickly and safely as possible and brakes at an appropriate height—at the knee or just above the floor.

Hand-Supported Squat

The hand-supported squat is also known as the Hatfield squat, a subject I wrote about previously. Adding hand support increases stabilization and eliminates some of the axial stress, allowing an athlete to provide a maximum effort through their legs.

This option eliminates many of the problems we find with conventional barbell supramaximal squats or with athletes who are not confident in a split stance. The handles allow the athlete to keep a good position and assist themselves on the concentric portion of the lift. It generally requires one less spotter than barbell squats. Across our athletes, we’ve found the maximum for hand-supported squats is about 25% greater than a conventional squat maximum.

Video 3. By holding on to handles, an athlete can maintain a good position while assisting themselves with the concentric part of the lift.

Hand-Supported Split Squat

The hand-supported split squat is the supramaximal movement I apply most regularly because it covers many sport contexts, MMA included. It has many advantages over standard split squat variations, the main one being the load. Supramaximal loading takes this to its most intensive application. For details on the set-up, I suggest reading “Supercharge Single Leg Strength with This Key Split Squat Variation”—you will need two spotters to assist on the concentric portion.

Video 4. The split stance is my preferred variation among the above exercises because it delivers powerful stressors in a semi sport-specific position. I suggest athletes have a decent level of competency with these lifts before applying supramaximal means.

Organizing the Session

Athlete status generally dictates the application of supramaximal work. I prefer a 2-day model, forgoing the 3-day model that Cal Dietz applied in his original methodology. That’s not to say I won’t employ a third day if circumstances allow. Often, I’ll apply an eccentric or isometric stimulus to only the heavy lower body exercise we’ve chosen, and keep the rest of the session at conventional loading and tempo and carefully pick and choose my other eccentric stimuli.

For example, choosing to perform eccentric neutral grip lowering and RDL work versus eccentric benching is a good use of an MMA fighter’s time, as the DOMS elicited by eccentric bench work can interfere with technical or tactical practice. Eccentric upper body work seems to lead to greater soreness than lower body soreness, which is an important consideration. But I let athlete feedback and individuation guide this process.

I generally place supramaximal work first in the session, and it’s often best paired with French contrast. The combination uses the enormous potentiation that supramaximal training brings and the benefits of training variable, rapid-lengthening velocities. It also counters one of the possible effects of intensive eccentrics, which is some concentric dampening. Alternatively, you could always pair it with necessary prehab exercises between sets.

Eccentric and isometric tempos aim to keep the exercise largely alactic <10s. The quality of repetitions dictates total time under tension, so we could do 1 rep for <10s or 2 reps for <5s each, for instance. The idea is to control hormonal response and avoid oxidative qualities that would come into play with longer durations of time under tension. Remember, the aim here is strength, not conditioning. Longer durations would spoil the intended effect of the supramaximal method. Additionally, clusters can be used to emphasize quality reps further.

The decision to employ each model is based largely on athlete readiness, but remember to expect some drop in readiness during such an intensive method. Generally, anything greater than 10% in our readiness metric (peak velocity week to week) means we’ll switch to a submaximal day. This need for plasticity has led to many templates that I apply when building an athlete’s program.

| Day 1 | Day 2 |

| Supramaximal Squat 105-110% 4 x 1,1 (cluster) <7s rep time French Contrast · Jump · Weighted Jump · Assisted Jump |

Supramaximal Squat 110-120% 4 x 1 <10s rep time French Contrast · Jump · Weighted Jump · Assisted Jump |

| Push-Pull (eccentric submaximal tempo) | Push-Pull (eccentric submaximal tempo) |

| Hinge-Hip flexion-Weaknesses (eccentric submaximal tempo) | Hinge-Hip flexion-Weaknesses (eccentric submaximal tempo) |

| Day 1 | Day 2 |

| Supramaximal Squat 105-110% 4 x 1,1 (cluster) <7s rep time French Contrast · Jump · Weighted Jump · Assisted Jump |

Submaximal 90% (clusters etc.)

4 x 1,1(2) 20s between reps |

| Push-Pull (eccentric submaximal tempo) | Push-Pull (eccentric submaximal tempo) |

| Hinge-Hip flexion-Weaknesses (eccentric submaximal tempo) | Hinge-Hip flexion-Weaknesses (eccentric submaximal tempo) |

A modified 3-day program is determined by athlete availability, but generally I place the extra day at the start of a week block. I’ve been influenced by the likes of Cameron Josse and ALTIS in making that first day a potentiation day, setting the athlete up for the week ahead. I generally avoid adding the middle dynamic day at 90% as outlined by Cal, as it’s just too much with a busy combined practice schedule.

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

| Submaximal lift (60-80% determined by) Contrast Method Extensive Jump etc. |

Supramaximal Squat 105-110% 4 x 1,1 (cluster) <7s rep time French Contrast · Jump · Weighted Jump · Assisted Jump |

Supramaximal Squat 110-120% 4 x 1 <10s rep time French Contrast · Jump · Weighted Jump · Assisted Jump |

| Submaximal Upper Contrast etc. | Push-Pull (eccentric submaximal tempo) | Push-Pull (eccentric submaximal tempo) |

| Hinge-Hip flexion-Weaknesses (eccentric submaximal tempo) | Hinge-Hip flexion-Weaknesses (eccentric submaximal tempo) |

Conditioning

I find that MMA fighters generally have good levels of work capacity, which comes from frequent game exposures across a number of sport contexts. That said, we can certainly add conditioning to prime the athlete at the periphery of his or her capacities. I’ll have athletes perform highly alactic work after or around supramaximal sessions in the form of heavy bag work, short sprints, and sport-based isometric holds (which are undervalued for their conditioning effect). This is to keep the congruence between lifting stimulus and conditioning stimulus to minimize the interference effect.

| Day 1 | Day 2 |

| Supramaximal Squat 105-110% | Supramaximal Squat 110-120% |

| Alactic Conditioning <10s Qualitative |

Alactic Conditioning <7s Qualitative |

Longer duration training or aerobic sessions can be added around this as needed, but often I find it not useful as most MMA, jiu-jitsu, and striking training is moderate-aerobic and continuous, making it difficult to justify this type of additional work.

Letting the Athlete Lead

By applying this method, we learned that the qualities that make fighters great are the qualities that make them a sponge for compressed training approaches. Tolerance for stress, robustness, and high levels of strength beget tolerance for stress, robustness, and high levels of strength—there is a reason this athletic population is tough.

Because of the intensiveness, I ensure an athlete-led approach that has communication as its underpinning. I always ask athletes how their training has been due to how variable it can be. I also chase them on recovery methods because of the pervasiveness of DOMS during the program. A gentle nudge to go sauna or perform a movement session can make the difference in readiness for the week ahead.

Closing Thoughts

This article explores the method as I apply it. Hopefully you can take something from it, even if it’s just a renewed consideration of how much stress we can apply beyond minimum effective doses to optimal effective doses. The supramaximal compressed method is not the only means available, as it lacks the skill acquisition component standard submaximal lifting has through more prolonged exposure. This is why I suggest having a few years of training accumulation, or at least moving loads more than twice bodyweight concentrically, on any of the supramaximal options presented.

Considering the short windows of opportunity MMA fighters have, it can be challenging to expose them to enough intensive strength methods throughout a training year. Compressed methods seemed like a gamble initially, due to the unknown of what an athlete can tolerate. But I learned to appreciate the method as a stressor we can apply like any other. Approached pragmatically—and with judicious application—it can be a powerful driver for change.

For further exploration of the underlying physiology of the supramaximal eccentric training and its positives and drawbacks, watch this video from the 2015 NSCA National Conference by Dietmar Schmidtbleicher.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Gavin L. Moir, et al. “The Development of a Repetition-Load Scheme for the Eccentric-Only Bench Press Exercise.” Journal of Human Kinetics, 2013; 38: 23-31.

Yessis. “Are Eccentrics (Negatives) For You?“SportLab: Building A Better Athlete.

Suchomel, T., et al. “The Importance of Muscular Strength: Training Considerations.” Sports Medicine, 2018.

Mike, J., et al. “How to Incorporate Eccentric Training Into a Resistance Training Program.” Strength and Conditioning Journal, 2015; 37(1): 5-17.

Jamurtas, A.Z., et al. “Comparison between legand arm eccentricexercises of the same relative intensity on indices of muscle damage.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, 2005; 95(2-3): 179-185.

Hyldahl, R.D., et al. “Lengthening our perspective: morphological, cellular, and molecular responses to eccentric exercise.” Muscle & Nerve, 2014; 49(2): 155-170.

Good article. The S+C if you would call it that of most MMA fighters just looks like a circuit training bootcamp.