[mashshare]

Strength training programs for sprinters often focus on total body, multi-joint exercises such as squats and deadlifts. These powerful exercises usually take up the majority of an athlete’s workout, such that there is only time for a few sets of auxiliary exercises. One type of exercise we believe is worthy of a sprinter’s attention are single-leg squats.

One reason to consider performing single-leg squats is they improve pelvic stability. If there is pelvic instability, it will take longer to absorb, store, and release energy during sprinting. As such, a sprinter’s ground contact time will be longer, and their stride length will be shorter.

Pelvic instability leads to longer ground contact time and shorter stride length. Single-leg squats are worthy of a sprinter’s attention because they improve pelvic stability. Share on XA coach may have some success giving their athletes instructions to avoid excessive rotational movements during sprinting, such as “cheek to cheek” for their arms or “knees up and forward” for their legs. However, if muscle weakness is the primary cause, coaching cues alone are not an efficient way to correct this problem. At least, not as efficiently as performing a few sets of corrective exercise. Let’s look at some numbers.

When you sprint, you are continually supporting your entire bodyweight on one leg and dealing with additional disruptive forces acting on the body. In his book, Running Rewired, Jay Dicharry estimates that the side-to-side forces your body has to deal with when you run equal 10-15 percent of your bodyweight, the acceleration/deceleration forces equal 40-50 percent of your bodyweight, and the vertical forces could be as much as 2.5 to 3 times your bodyweight! With such high levels of stress, it’s no wonder that Dicharry’s book focuses on resistance training to correct poor running mechanics, especially variations of single-leg squats.

Although single-leg squats obviously work the quads, sprinters and their coaches should consider that they also strengthen the glutes. As a review, the glutes consist of three muscles: the gluteus maximus, the gluteus medius, and the gluteus minimus.

The glute medius also has three subdivisions: anterior, middle, and posterior. Its functions include abducting the hip, stabilizing the pelvis, and eccentrically controlling internal rotation and hip adduction—as such, this muscle plays a major role in sprinting. Not only may a weakness in the glute medius cause excessive rotation of the pelvis, but it may also cause the knees to buckle inward, increasing the risk of knee ligament and overuse injuries.

With that background, let’s address the question, “What are the best exercises for the glute medius?”

The Science of Stability Training

In 2009, the Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy (JOSPT) published the results of a study that looked at the effectiveness of 12 popular glute exercises. One of these exercises was the forward lunge, which had significant activation of the glute medius.

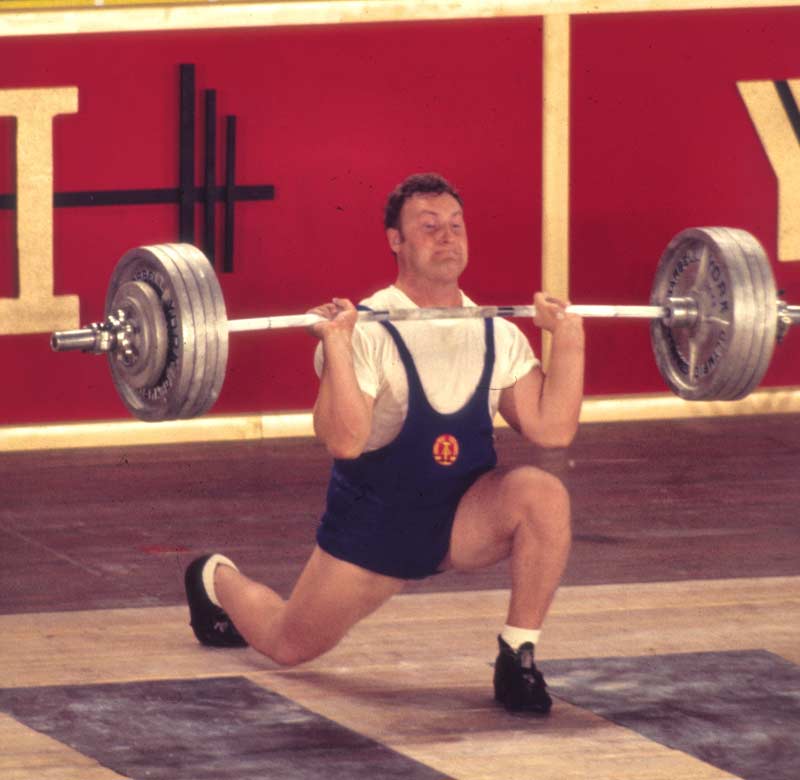

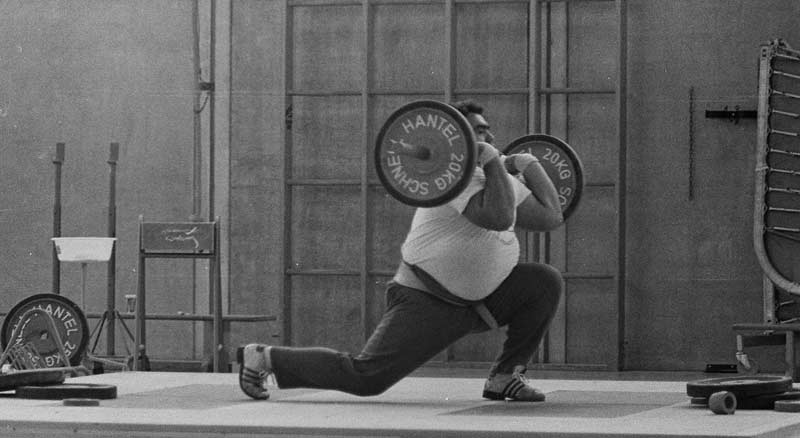

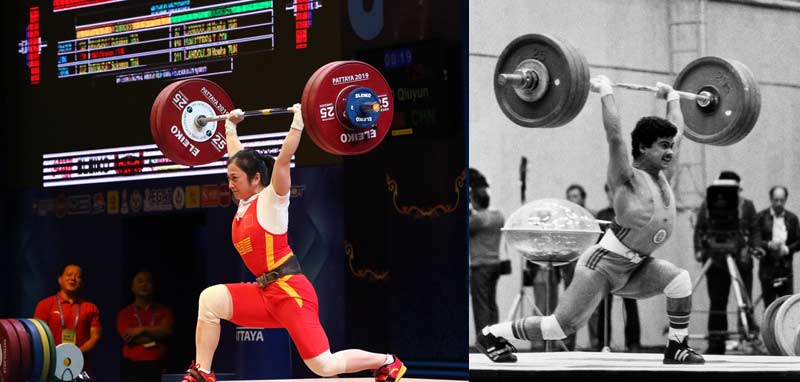

Forward lunges have become a favorite of many sprint coaches, who believe that they are more sport-specific to sprinting than squats. Many other types of athletes perform them. In fact, in the early days of the sport of weightlifting, lifters often used the split-style snatch and the split-style clean rather than the squat style. The split-style receiving position resembles the low position of a forward lunge. Thus, as part of their training, some of these lifters often performed lunges to increase their strength and stability in the receiving position.

Although a weightlifter can potentially catch the bar in a lower position with the squat style, thus enabling them to lift more weight, many early lifters who practiced the split style could achieve extremely low receiving positions. Few lifters use the split style today, but some may perform lunges to prevent muscle imbalances developed by performing the jerk. In fact, Vasily Alexeev, a two-time Olympic champion from Russia who broke 80 world records and was the first to clean and jerk 500 pounds, performed front lunges with a barbell.

One of the exercises in the JOSPT study with the highest ranking for glute medius activation (ranked #2 behind the side-lying hip abduction) was the single-leg squat. It also beat out the single-limb deadlift for the highest activation of the gluteus maximus. Before taking a closer look at the single-leg squat, let’s examine some of the drawbacks of two of the most popular glute exercises: lateral band walks and hip thrusts.

Lateral band walks have become the “go to” exercise for the glute medius in physical therapy and “functional training” programs. This makes sense, as it ranked #3 for glute medius activation in the JOSPT study (but, interestingly, last in gluteus maximus activation!). As a plus, it’s performed from a standing position.

According to Canadian strength coach and posturologist Paul Gagné, the tendon signals that correlate to elastic strength storage and release are stronger with standing exercises. Unfortunately, when used with high levels of resistance, lateral band walks place considerable shearing stress on the knees. They also do little to develop body awareness, which is important because sprinters must deal with instability to run fast. Although lateral band walks strengthen the glute medius, exercises that improve body awareness should take precedence in a sprinter’s training.

Although lateral band walks strengthen the glute medius, exercises that improve body awareness should take precedence in a sprinter’s training. Share on XHip thrusts were not one of the exercises in this study, but consider that athletes perform these types of glute exercises supine and in a stable environment. Using the definitions developed by sports scientists Mel Siff and Yuri Verkhoshansky, the hip thrust should be classified as a structural or bodybuilding exercise, and as such has little carryover to athletic performance. That said, let’s look at some real-world research.

In an eight-week hip thrust study involving 21 college athletes (15 males, 6 females), researchers found that “…maximum hip thrust strength through use of the barbell hip thrust does not appear to transfer into improvements in sprint performance in the collegiate level athletes.” It’s certainly fine for sprinters to occasional use exercises such as the hip thrust, especially for glute activation before sprinting or lifting, but performing it on a regular basis with maximal weights may not be the most effective use of an athlete’s training time if the goal is to run as fast as humanly possible.

Getting back to single-leg squats, one variation we like for sprinters is called a “pistol squat,” so named because at the bottom of the exercise your body takes the shape of a hand pistol. Although our main focus here is on sprinting faster, consider that pelvic stability is also essential for moving laterally and changing directions because you must be able to control the high forces your body is exposed to while moving in this manner.

Think about it: When you plant one foot to change directions, you’re pretty much standing on one leg and performing a partial single-leg squat! With all the side-to-side movement that takes place in athletics, especially in sports such as soccer and basketball, those extra fractions of a second needed for an athlete with poor pelvic stability to maintain their balance can be the difference between making the play or being part of an “ankle breaker” highlight video.

When you plant one foot to change directions, you’re pretty much standing on one leg and performing a partial single-leg squat! Share on XAnother advantage of single-leg squats—at least all but one of the versions we will discuss here—is that they work the legs through a full range of motion. If an athlete focuses on partial range-of-motion leg exercises (such as the so-called Bulgarian split squat), not only are the muscles around the knee inadequately developed, the connective tissues may lose their elasticity and their ability to react to high stress.

If you follow the sport of weightlifting, you may have seen athletes dropping heavy barbells on their legs with their ankles and knees in awkward positions, but not suffering injuries. Further, hamstring, ACL, and ankle injuries are practically non-existent in this sport. Contrast that with sports such as soccer, volleyball, and football, where approximately 70% of injuries to these areas of the body are non-contact. Perhaps full-range leg exercises, even those such as the clean and snatch in which you bounce out of the bottom of the squat, are the future of pre-hab training?

The Workouts

Many strength coaches avoid single-leg squats because most athletes, due to flexibility or stability issues, cannot perform a full pistol squat the first time they try it. Rather than avoiding an exercise that can help correct these problems, how about trying a progressive system that enables athletes to not only to perform the exercise, but to do so with resistance!

Video 1. Marybeth Fitzsimmons, a multiple high school state champion sprinter from Rhode Island, demonstrates a progression to perform pistol squats using several of the exercises discussed in this article. Fitzsimmons earned a full athletic scholarship for track at Northeastern University, excelling in the long jump and the short sprints.

The program we will share with you contains four workouts, each building on the previous one. If an athlete can already do a pistol squat, they can jump to Workout 4. For everyone else, perform the workouts in the order presented. Some athletes will progress faster than others, which is fine—the goal is to master one sequence of exercise before proceeding to the next. Here are the workouts:

Workout 1

The first exercise requires little stability, but it works the legs through a full range of motion, even if the athlete has mobility restrictions. The second exercise, although performed through a partial range of motion, focuses on the glute medius and increases body awareness.

- Pistol Squat, Assisted: 2 sets x 10 reps, each leg, rest 30 seconds

- Single-Leg Squat with Lateral Press, Big Toe Up: 2 sets x 10 reps, rest 30 seconds

Workout 2

This workout increases the intensity of the first exercise performed in Workout 1, whereas the second is another, more stable version of the pistol squat.

- Pistol Squat, Assisted, Eccentric Emphasis: 2 sets x 5 reps, rest 30 seconds

- Single-Leg Friction Squat: 2 sets x 5 reps, rest 30 seconds

Workout 3

This workout introduces the full pistol squat, with the first exercise being a more stable version of the full movement. The second exercise is the full pistol squat, or at least as close as possible to a full pistol squat. The workout should continue until the athlete can perform five full repetitions of the pistol squat.

- Pistol Squat Between Boxes: 2 sets x 10 reps, rest 30 seconds

- Pistol Squat: 2 sets x 5 reps, rest 30 seconds

Workout 4

At this point, the athlete should be able to perform full pistol squats without any assistance. Thus, the first exercise is the pistol squat, whereas the second is the pistol squat performed with additional resistance.

- Pistol Squat: 1 set x 10 reps, rest 30 seconds

- Pistol Squat with Weights: 3 sets x 5 reps, rest 30 seconds

A few notes: The reps indicated are for each leg, not the total reps for a set. Next, these are stability exercises and, at first, should be performed at a relatively slow tempo—a good general guideline when you first try these exercises is that it should take twice as long to lower your body as it does to raise it. Also, as these are single-leg exercises, minimal rest is needed between sets because as one leg works, the other rests. This means each workout can be finished in about 6–8 minutes, depending on how long it takes to set up for each exercise.

The Exercises

Here are the details of the exercises, along with illustrations of each.

Pistol Squat, Assisted

One reason many athletes cannot perform a single-leg squat is that they lack the mobility in the ankles. An option is to perform partial single-leg squats and calf stretches, gradually increasing the depth of the exercise as their mobility improves. This exercise has more “bang for your buck,” as it enables you to perform a full range of motion of the legs from the first workout, increasing mobility in the lower extremities along the way.

The exercise is performed inside a power rack. You position a barbell at a height level of about the top of your pelvic bone. You need to set the bar so that when you perform the exercise, the bar pulls against the support (so that you don’t fall backward). Lift one leg and keep it off the floor throughout the exercise. Squat as low as possible, using your hands for support and leaning backward if necessary, then pull yourself upward. Check out the accompanying video to see exactly how this exercise should be performed.

During this workout, you should move slowly to ensure proper alignment. When you progress to Workouts 2–4, however, it may be okay to have a slight bounce out of the bottom, as these tissues have elastic properties.

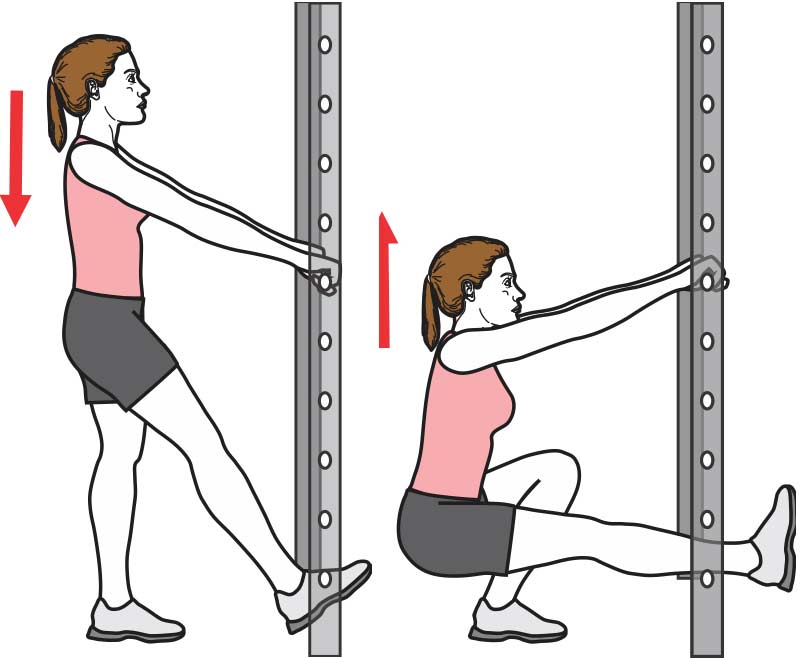

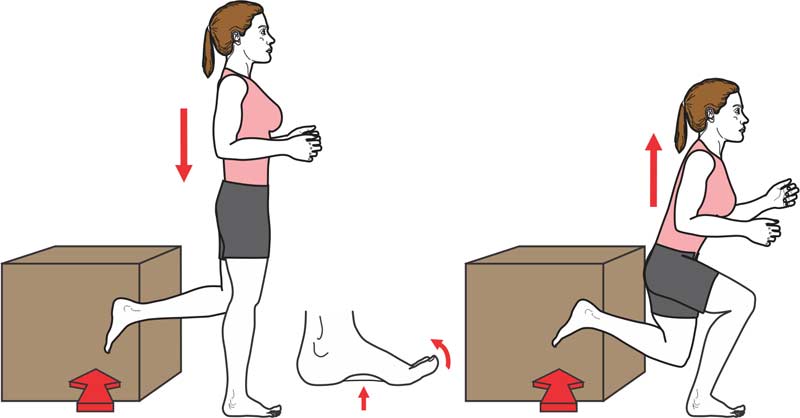

Single-Leg Squat with Lateral Press, Big Toe Up

Coach Gagné created this unique exercise to strengthen the glute medius, help correct valgus feet (i.e., fallen arches), and improve body awareness. As an experiment, try performing this exercise before sprinting and then try performing lateral band walks before sprinting—you’ll find that Gagné’s exercise creates a better sense of stability. We should also mention that this exercise is especially valuable for hurdlers, as these events can lead to imbalances in the glutes.

Coach Gagné’s single-leg squat with lateral press and big toe up helps with stability and is especially valuable for hurdlers because it corrects imbalances in the glutes. Share on XThis exercise is performed barefoot alongside a high box (or another sturdy object). Stand on one foot with the other leg bent and behind you (forming a 45-degree angle). Lift the big toe of the foot on the floor. The primary muscle that lifts the big toe is the extensor hallucis longus, and it is important for correcting a valgus foot because it creates lateral tension on the foot. Press the rear foot alongside the box, which will increase the work of the glute medius. Now do quarter squats, maintaining the pressure on the box and keeping the big toe up.

Pistol Squat, Assisted, Eccentric Emphasis

This is the same setup as the assisted pistol squat, but with this version you challenge yourself on the lowering phase. From the start position, let go of the bar, keeping your hands about an inch away from it. Lower yourself slowly, but grasp the bar for support if you lose your balance. When you reach the bottom position, grasp the bar and use your arms to assist you on the way up.

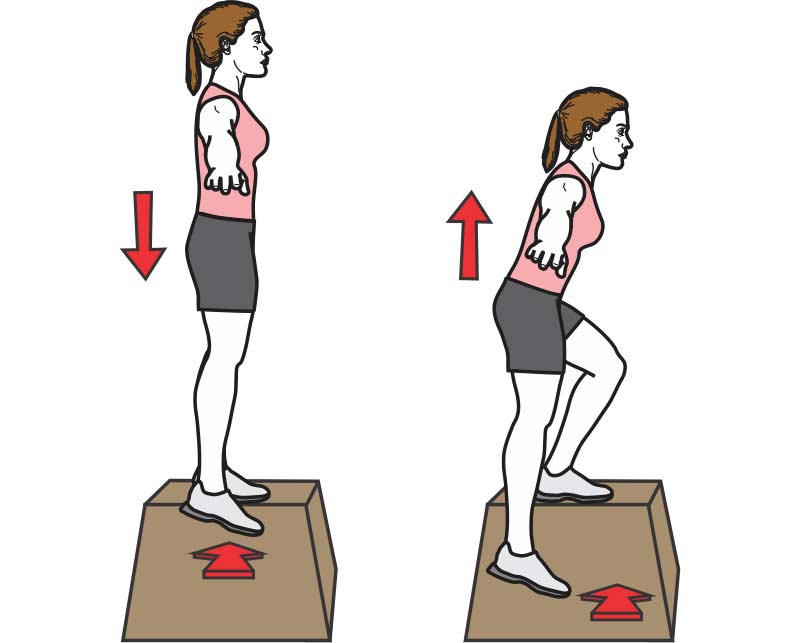

Single-Leg Friction Squat

This exercise was created by physical education teacher Bob Rowbotham. You need a sturdy box that won’t tip if you stand on one side of it (and it’s a good idea to have someone brace the box to prevent it from tipping).

Stand on one edge of the box so that your outside leg is in free space. Press the side of the free foot against the edge and keep pressure on it as you slowly lower yourself. When you reach the bottom, use that free leg to push off the floor and help you return to the start.

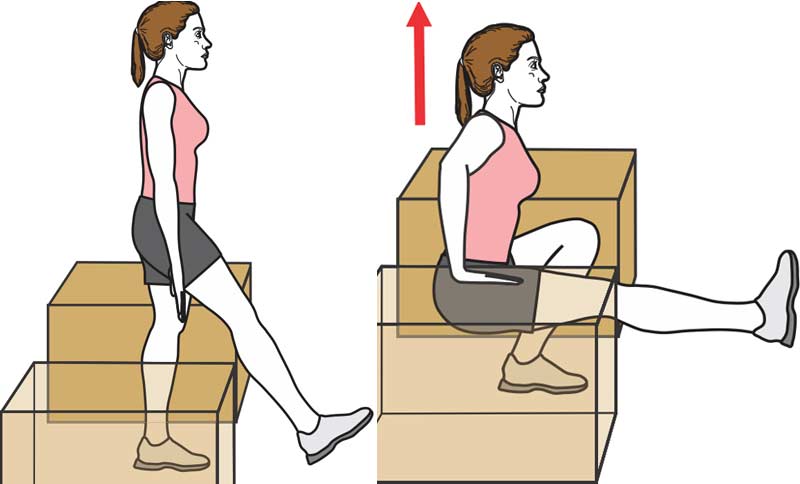

Pistol Squat Between Boxes

This exercise is a full pistol squat, but it’s performed between two boxes so you can use your arms to assist you at the bottom of the movement. The boxes need to be about knee height, spread slightly wider than shoulder-width apart.

Stand between the two boxes with hands at your side. Lift one leg high enough so that it doesn’t touch the floor during the exercise. Bend your leg, but catch yourself with your arms as you near the bottom position to slow yourself down and increase your stability; then use your arms to help push yourself up to the start.

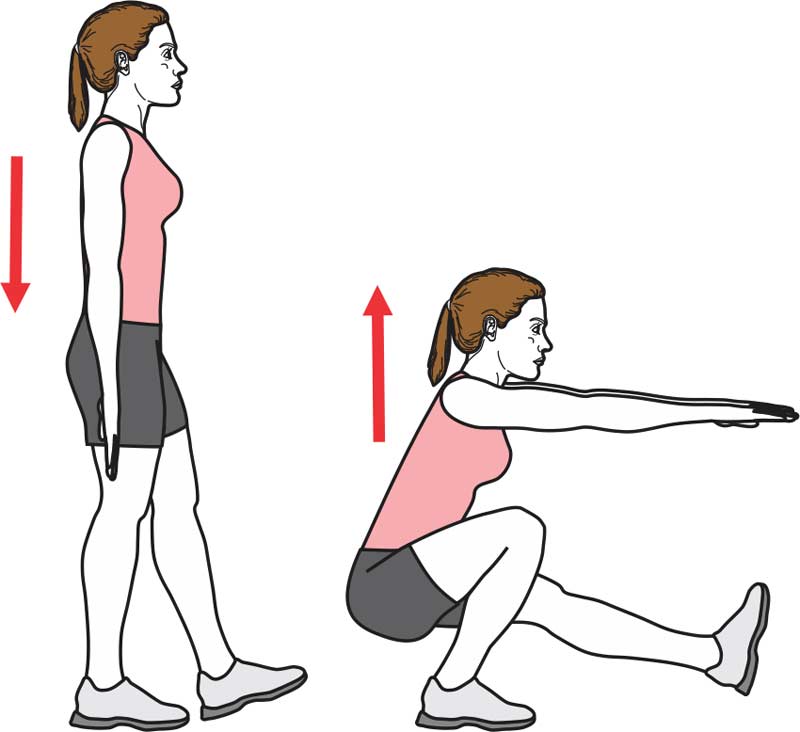

Pistol Squat

This is the full pistol squat. However, it’s not expected that you’ll be able to perform all the recommended reps for the sets prescribed at first. As such, you should perform as many full reps as possible for each set, then do the remaining as partial reps.

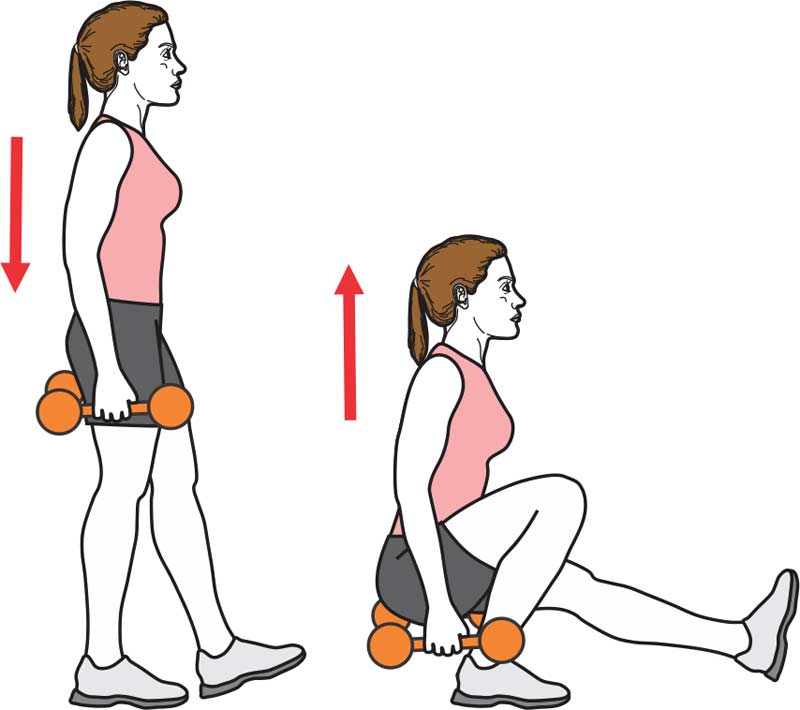

Pistol Squat with Weights

After you’ve mastered the pistol squat, it’s time to increase the intensity of the exercise by holding weights. Dumbbells and kettlebells are ideal ways to increase resistance. Perform the exercise just like a pistol squat, but with weights held at your sides.

A Simple Solution as the Best Solution

Applying the principle of Occam’s Razor to athletics, the simplest solution to a sprinting problem is often the best solution. The single-leg squat is one simple solution to helping sprinters maintain optimal pelvic alignment to achieve the fastest times. Give the workouts presented here a try and see what this remarkable exercise can do for you!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

Anderson, Frank C. and Pandy, Marcus G., “Storage and Utilization of Elastic Strain Energy During Jumping.” Journal of Biomechanics. 1993; 26(12):1413–1427.

Bishop, C., et al. “Heavy Barbell Hip Thrusts Do Not Effect Sprint Performance: An 8-Week Randomized–Controlled Study.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2019; 33:S78–S84.

Dicharry, Jay. Running Rewired, 2017, VeloPress, pp. 2-3.

Distefano, L.J., et al. “Gluteal Muscle Activation During Common Therapeutic Exercises, Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy.” 2009; 39(7):532–40.

Goss, K. “The Case Against Stability Training.” Bigger Faster Stronger, March/April 2007, pp. 70–72.

Siff, M. and Verkhoshansky, Y. Supertraining, 1999, 4th Edition, Supertraining International, Denver USA 1999,pp. 7–8. (1st edition, 1993)

Kim Goss was a strength coach for the U.S. Air Force Academy and has a master’s degree in human movement.

Kim Goss was a strength coach for the U.S. Air Force Academy and has a master’s degree in human movement.