[mashshare]

The Nordic curl proved to be a simple yet valuable exercise for sprinters to help prevent hamstring injuries; step-ups and Bulgarian lunges, on the other hand, did not fulfill their promise of turning athletes into cheetahs. The hip thrust is one more exercise that has proven disappointing for sprinters. Let’s take a closer look at why this glute builder doesn’t live up to its hype and explore how you can do better.

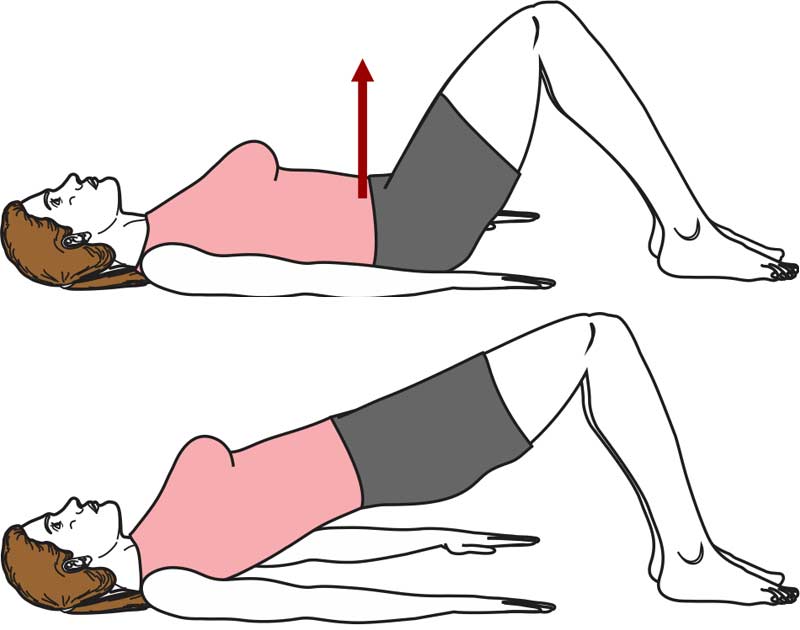

To avoid confusion, I’ll mention that the term hip thrust was first used to describe a lower body sled popular with football players. In physical therapy, hip thrusts belong to a class of exercises called pelvic bridges often used in lower back rehab protocols. Don Chu, Ph.D., a jumps coach known for his work in plyometrics, introduced me to this exercise during a physical education class I took from him in 1982.

To be clear, I’m not coming from the perspective that bodyweight hip thrusts should never be performed. Again, they are commonly used in physical therapy. However, you need to consider that there are risks associated with performing hip thrusts with a heavy barbell resting across your pelvis. With this background, let’s look at how we got into this state of confusion about glute training in the first place.

EMG Results and the Hip Thrust

We can track much of the initial hype over the hip thrust to studies using electromyography (EMG) machines, which measure the electrical activity of muscles. This information is especially important in the medical field for identifying neuromuscular diseases. That said, we have to question the value of EMGs for determining how useful an exercise is for improving athletic performance. Just ask sports scientist William Sands, Ph.D.

Sands did his dissertation on EMGs, saying these machines could determine which muscles are active and when they’re active. “However, after that it gets a little dicey. There is a nice linear relationship between magnitude of EMG and muscle force, but the relationship is only valid for isometric tension.” Since most athletes want to demonstrate strength at fast speeds, EMG results have limited real-world application to athletics. There is also the issue of how EMG testing is administered.

Since most athletes want to demonstrate strength at fast speeds, EMG results have limited real-world application to athletics. #speed #EMG Share on XThe most accurate EMG tests involve inserting needles into the muscles and performing maximal muscle contractions. Besides the challenge of finding volunteers to perform squats with needles stuck in their glutes, this practice can cause nerve damage. Further, the results of any hip thrust study can be misleading because participants perform exercises on the floor to lessen interference from other muscles. Sports coach and therapist James Jowsey addressed this issue when he said that, as the pelvis lifts during this exercise, “the only neurological drive goes to the glutes, hence the high EMG reading for the bridge.”

One well-publicized EMG personal experiment on hip thrusts was conducted by a fitness trainer who used less accurate surface EMGs to compare the hip thrust with other exercises for glute activation. He found that the highest reading for the gluteus maximus was not with the hip thrust. In fact, the single-leg reverse hyper produced double the EMG measurement, and the reverse hyper was also nearly double. He followed it with another study in which the hip thrust produced a slightly higher EMG reading than the reverse hyper. This second study, though, was rather pointless because he used a maximal load on the hip thrust and a submaximal load on the reverse hyper.

One study that looked at hip thrusts vs. back squats for improving several qualities of athletic fitness was part of a Ph.D. thesis. The hip thrust came out on top. However, the study only involved two people, which sent up my first red flag because it had poor “statistical power” (to use this individual’s own words).

My second red flag was that the subjects were twins, so it would be difficult to replicate the study. My third red flag was that the subjects performed either hip thrusts or squats, but did not switch protocols in the middle of the study. My fourth red flag was that the student shared the results of his research on social media before his thesis was approved, a practice my academic colleagues tell me is frowned upon. But my fifth, and darkest, red flag was the type of squat performed in the study.

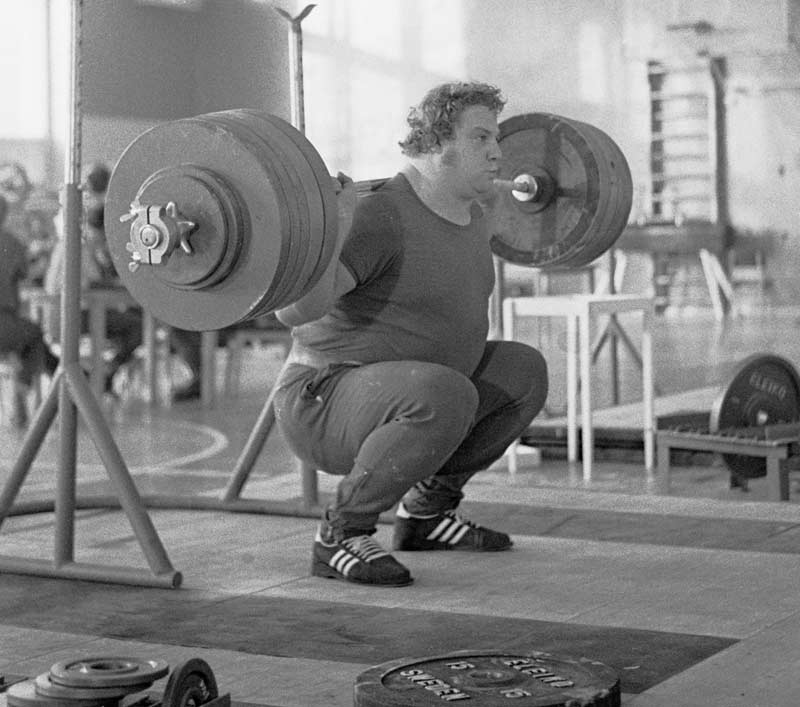

From looking at the photos from the study the student shared on social media (which, for some bizarre reason, also included an inappropriate photo of the subjects grabbing each other’s glutes), the squats performed did not appear to reach the depth that would pass the judging standards of any powerlifting federation.

Contrast that to a 2014 paper on squats, which explained that squatting to an appropriate depth was critical to work the posterior chain muscles adequately: “Without squatting to the proper depth, the hamstrings and gluteus muscular complex may not be adequately challenged. Specifically, training at shallower knee flexion can influence quadriceps dominant sport skill performance that can limit performance and increase injury risk. Likewise, training at deeper depths will help benefit motor control positions that are common to sport.”

Will Hip Thrusts Help Sprinters Run Faster?

The short answer: probably not.

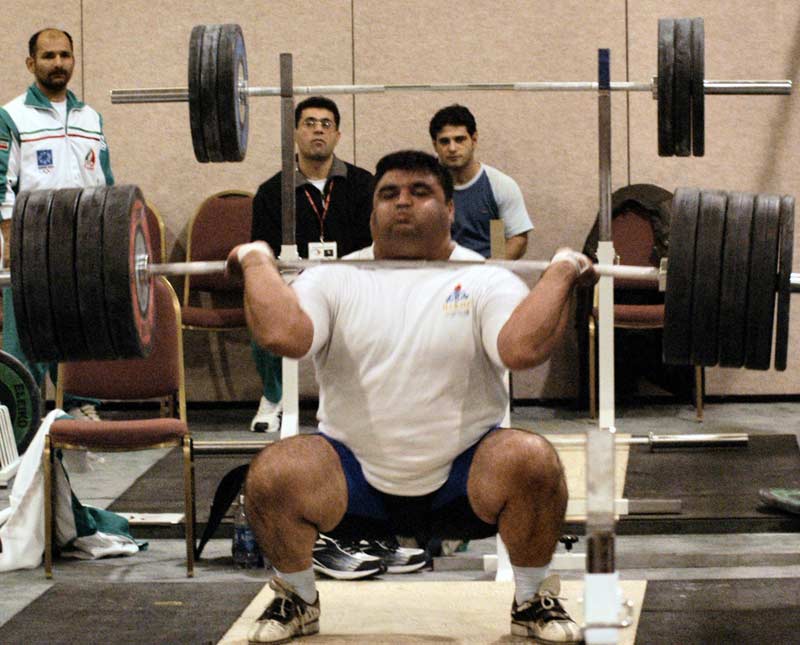

Let’s start with a six-week study that compared the hip thrust to the front squat for improving short sprinting speed. The research group included one individual who sold hip thrust benches. The authors concluded, “Potentially beneficial effects were observed for the hip thrust compared to the front squat in 10- m and 20- m sprint times.” Pretty shocking, until you see how the study was designed.

Rather than performing full front squats, the subjects performed parallel squats. If you’re going to play that game, then how about only performing partial hip thrusts? What’s just as troubling are the loading parameters of the front squat. Here is what they did:

- Week 1: 4 x 12

- Weeks 2-3: 4 x 10

- Weeks 4-5: 4 x 8

- Week 6: 4 x 6

Say what? Sets of 12?

With over four decades in the Iron Game, I’ve never seen any published athletic fitness workouts that recommended sets of 12 in the front squat. Holding a barbell on the shoulders compresses the chest and inhibits normal breathing, making it difficult to perform higher repetitions. Performing more than 3 repetitions also often leads to a breakdown in technique as the upper back muscles fatigue quickly, forcing an individual to use especially light weights. In this study, the average number of reps was 9. In my weightlifting circle, we often refer to sets of 4 reps in the front squat as cardio!

As for the hip thrusts in this study, the same number of reps were performed as the front squat. This exercise prescription doesn’t make sense because the range of motion is considerably shorter with a hip thrust than a squat, so the time under tension will be different and thus the training stimulus. Let me explain.

Although an average of 9 reps per set may be considered a mass building protocol for the front squat that transfers poorly to sprinting, performing the same repetition bracket for the hip thrust could be considered a relative strength protocol that would increase maximal strength with minimal increase in body mass.

The researchers should have used time-under-tension repetition brackets, performing both exercises for the same amount of time for each set. You wonder what the results would have been using, let’s say, sets of 2-3 front squats. And it should be noted that in 2017, one of the study’s researchers admitted in a podcast that the hip thrust might have a better transfer to running, not sprinting.

Because of all the hype surrounding the hip thrust, researchers from the UK decided to conduct an 8-week study on the effects of hip thrusts on athletic performance. These researchers apparently were not selling hip thrust benches so had no potential financial gain from the results. The study involved 21 college students (15 males, 6 females).

When hip thrust strength improved dramatically, the effects did not transfer to #sprinting speed. #hipthrust Share on XAlthough hip thrust strength improved dramatically, the effects this strength had on sprinting speed were underwhelming. Here’s what the UK researchers said: “These findings suggest that increasing maximum hip thrust strength through use of the barbell hip thrust does not appear to transfer into improvements in sprint performance in collegiate level athletes.” Well, so much for that theory.

Is There Any Harm in Doing Hip Thrusts?

The short answer: perhaps.

A human spine is a column-like structure that is better suited for handling vertical compressive forces than the horizontal shearing forces that the hip thrust exerts on the spine. As for real-world evidence, sports coach Justin Kavanaugh followed the progress of 100 athletes performing hip thrusts. Forty of these athletes had back surgery or a history of back pain. Guess what?

“The athletes who did not perform the heavy barbell hip thrust had very little problems in terms of pain in their lower back. Those athletes that did perform the heavy barbell hip thrust, even the ones with no history of back pain or injury, were having issues shortly after finishing with this specific lift.”

Another issue with weighted hip thrusts is that the prolonged pressure of the bar resting directly over the pelvis compresses the fascia. The body may react to this stress by laying down more fascia, which makes this connective tissue less “pliable” (as Tom Brady’s trainer would say). The eventual result is disruption of the fascial system. If one of your training goals is to improve elastic strength so you can sprint faster, you should avoid performing activities that compromise the performance of these tissues.

But wait. What about those athletes who have glutes that “don’t fire”? Here’s the deal. The glutes help us maintain upright posture (which is why apes, who possess minimal glute development, have trouble standing for long periods). If your glutes didn’t fire, every time you took a step you would fall flat on your face.

You can, however, have glutes that are inhibited in their ability to contract if there is tightness in their antagonistic (opposing) muscles, specifically the muscles that flex the hip. This interference is known as Sherrington’s law of reciprocal inhibition. What this means is that before signing up for a “Bum Blasting Boot Camp” because someone said your glutes weren’t firing, try stretching your hip flexors.

Better Options to Develop Elastic Strength for Sprinters

If I’ve led you to become a bit skeptical about using hip thrusts in an athletic fitness program, let’s go a step further and consider some alternatives. But before sharing these with you, consider that one reason the hip thrust may not improve sprinting is that the exercise does not address the timing of the glute muscles in dynamic athletic activities. What do I mean by timing?

Performing an exercise that focuses on training one glute muscle at slow speeds (to avoid hyperextension of the spine) could affect the timing of how the glutes contract and relax in sprinting. And perhaps, as possibly demonstrated by the UK study, the glutes can become a weak link in the posterior chain that will adversely affect your ability to run fast. I say this because, if you don’t time your deceleration properly when the foot strikes the ground during sprinting, the amount of force you apply into the ground will be deficient. I discussed this topic in detail in my previous article on elastic strength, using the example of Usain Bolt’s knee action in sprinting.

#Flywheels offer fast eccentric loading to work on the timing of glute activation during #sprinting. Share on XSince the reverse hyper got gold stars for its EMG results, consider that one of the best ways to perform it would be a horse-stance reverse hyper using a flywheel pulley for resistance. These flywheel machines provide fast eccentric loading that enables you to work on the timing of glute activation during sprinting.

Video 1. The reverse hyper can be performed unilaterally with a flywheel pulley machine. This machine lets you train the muscles that extend the hips at fast speeds.

To take this flywheel exercise a step further, you could perform a horse-stance kickback using a flywheel pulley. This variation strongly involves the quadriceps, as these are the muscles used when applying force into the ground during a sprint. Stride length is one of the keys to improving sprinting speed, and powerful athletes can apply more force into the ground to propel themselves further with each stride. Sprint coach Charlie Francis was a big believer in this type of movement, which he had his athletes perform on a horizontal leg press machine.

Video 2. The horse-stance kickback using a flywheel machine is an advanced exercise for developing sprinting power.

One possible workout sequence for sprinters would be to do a few sets of the reverse hyper flywheel exercise to strongly activate the glutes and then transition into the more advanced variation. After that, sprinters could progress to standing glute exercises with a flywheel—speed-specific exercises I could discuss (along with several others) in a future article if there’s any interest.

The lesson here is that coaches should stop looking for revolutionary isolation-type exercises and piecing them together into some strange Gestalt system of superior program design—remember the story about the blind men trying to describe an elephant? Muscles work together with the fascia to create biological springs to produce maximum speed and power. In other words, partial training produces partial results. This brings up the issue of pelvic stability.

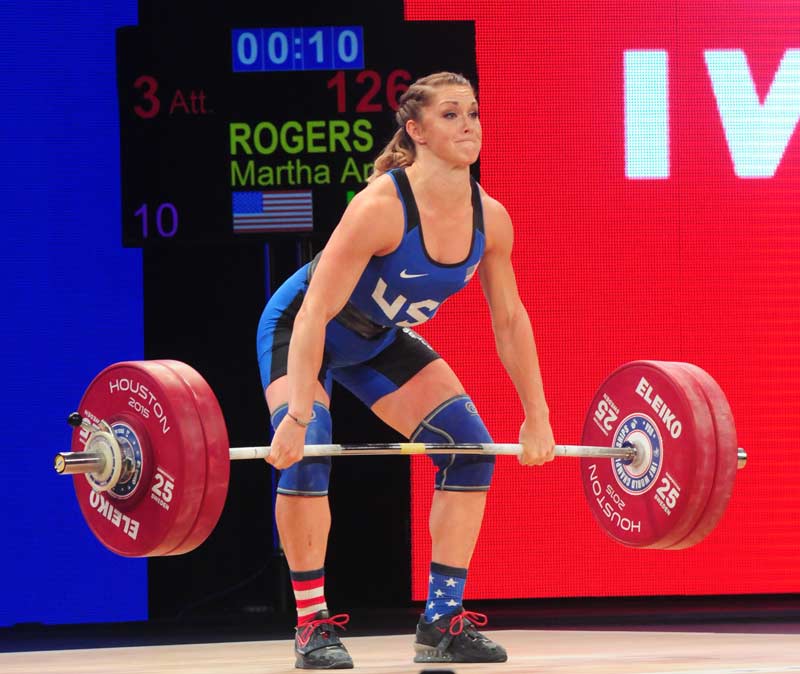

One of the primary functions of the glutes during sprinting is to stabilize the pelvis, and there’s not much core stability involved in performing a hip thrust while lying on your back. In contrast, many exercises can be performed that address this issue. And the exercises that top the list for core stability are the Olympic lifts.

The snatch and clean and jerk are large amplitude movements performed at high speeds that develop the elastic qualities of the tissues and promote pelvic stability. In other words, they make you more powerful through a full range of motion. These lifts are not to be confused with the partial power clean nonsense promoted by those functional trainers who have their athletes shuffling across plastic ladders that teach them how to run in place really fast.

Concluding Thoughts

When you look at the preponderance of research and real-world evidence that dispute the claims of those promoting the hip thrust, it’s obvious that this exercise has little value to a sprinter. The takeaway is that rather than jumping on the latest training “secret” that carries the promise of dramatically improving athletic performance, look at these discoveries with a journalist’s eye and carefully read the research to see its true value, if any.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

Koch, Fred. “EMG Testing: Does It Tell All?”

Jowsey, James. “Why the Glute Bridge Will Not Make Your Squat Better.”

IPF Technical Rules Book 2016.

Meyer, G.D., et al. “The Back Squat: A Proposed Assessment of Functional Deficits and Technical Factors that Limit Performance.”Strength and Conditioning Journal.

Dietmar Schmidtbleicher, Ph.D., NSCA National Conference, San Diego, California, 1990.

Contreras, B., et al. “Effects of a Six-Week Hip Thrust vs. Front Squat Resistance Training Program on Performance in Adolescent Males: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Strength and Conditioning Journal.

Bishop, C.,et al. “Heavy Barbell Hip Thrusts Do Not Effect Sprint Performance: An 8-Week Randomized–Controlled Study.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

Kavanaugh, J. “The Heavy Hip Thrust Is Ruining Our Backs and This Industry.”

Francis, Charlie. Charlie Francis Training System, p. 50-51.