Tim Rabas has served as Associate Director of Football Strength and Conditioning/Director of Football Athletic Performance for North Carolina State since January 2016. He was previously on the Wolfpack’s strength staff from 2012-2014, before spending 2015 as the Associate Football Strength & Conditioning Coach at Nebraska. Prior to 2012, Tim spent six years at Oregon State as an assistant strength and conditioning coach, working with the football program. He was also the Director of Strength & Conditioning for men’s basketball, volleyball, baseball, wrestling, swimming programs, and performance camps at OSU.

Freelap USA: The field of strength and conditioning has evolved with science and technology, but coaching competence is now in a dark age. Looking at the craft as a whole, how has the coach regressed as an instructor over the last decade?

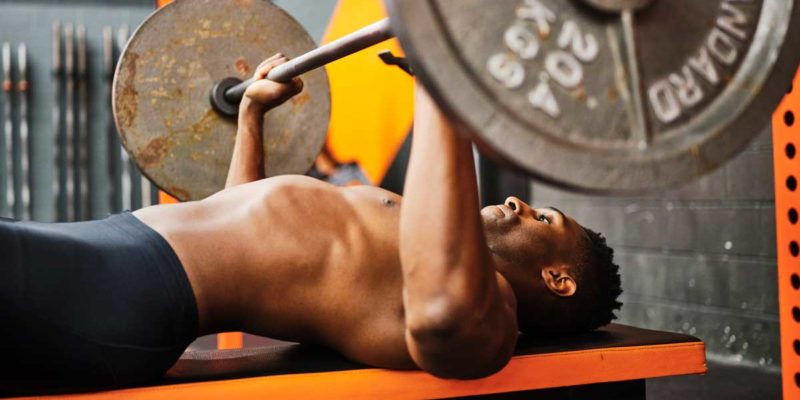

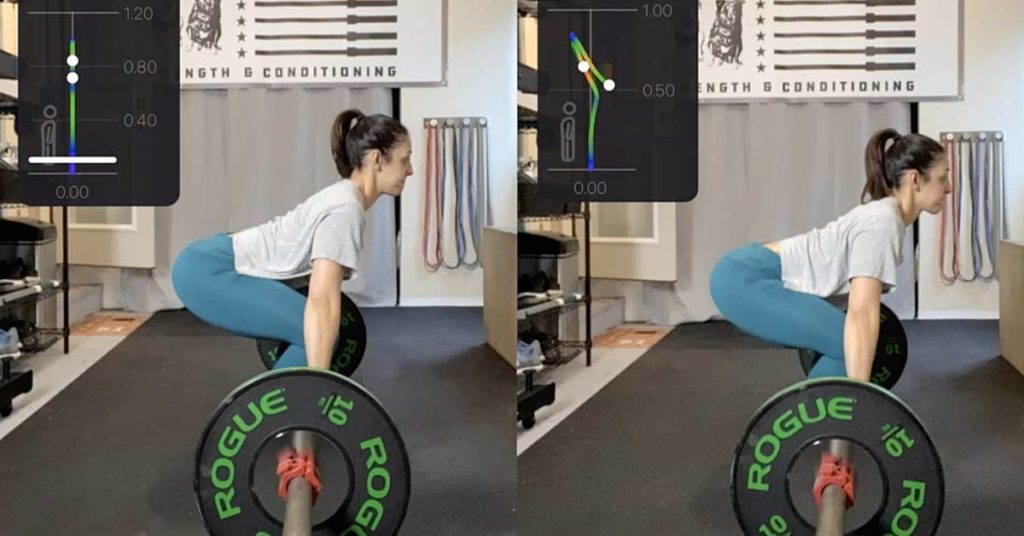

Tim Rabas: Technology is a resource that can provide more direction to maximizing the genetic potential of our athletes. The data helps establish our training periodization model that we provide to our sport coaches, athletic trainers, and athletes. The key to maximizing technology is tied to movement measured and the level of true proficiency. For example, the bar speed of doing a clean pull has many technical aspects much more critical than simply looking at the “velocity.”

First, we have to be able to identify and teach the fundamentals and provide ample opportunities to develop them. Progression and regression are critical to enhancing movement capacity. Simplify complex movements into parts. Get familiar with the exercises and mechanics that are taught within the program. Our experience provides the frame of reference for the cues we use. Lack of familiarity will make it difficult to explain it to the athlete.

Our experience provides the frame of reference for the cues we use. Lack of familiarity will make it difficult to explain it to the athlete. Share on XThe coach leading the process requires knowledge, patience, and discipline. We establish the pace and level of expectation. The more we understand, the more we can manipulate the variables. We select movements because they scientifically support our goal of athlete performance, but only if the movements are done correctly. This is the blend of both the SCIENCE and ART of coaching. We have to be willing to be the fool in order to develop expertise. Learn to think in the box before going outside of it.

Freelap USA: Player monitoring is popular in football, but decisions afterward seem to be nothing more than volume and intensity tweaks. How do you use the latest technology to write better workouts and teach? It’s not like VBT is new.

Tim Rabas: In 2002, I was an intern with the Chicago Bulls. Al Vermeil has always been ahead of his time in the profession. Al designed The Berto Center training facility in 1992 with racks, platforms, barbells, dumbbells, and a multi-lane track. He developed his own timing devices that measured acceleration, velocity, and reaction time.

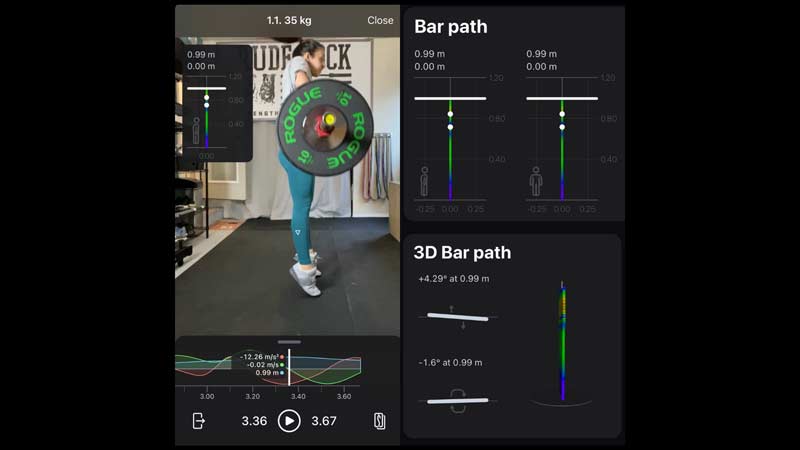

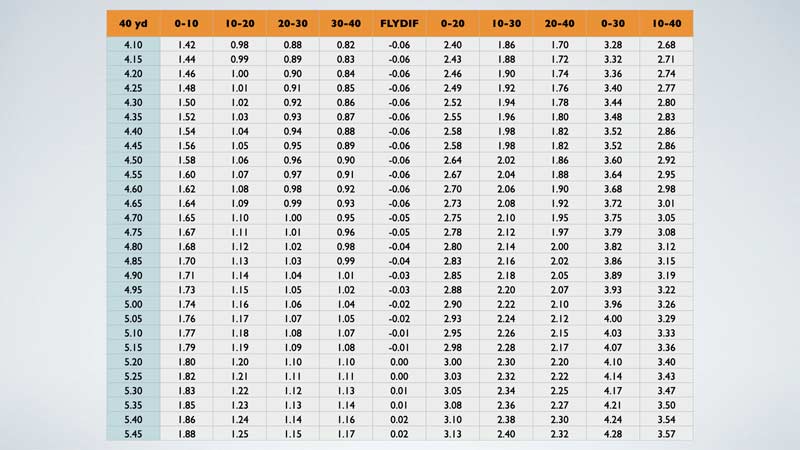

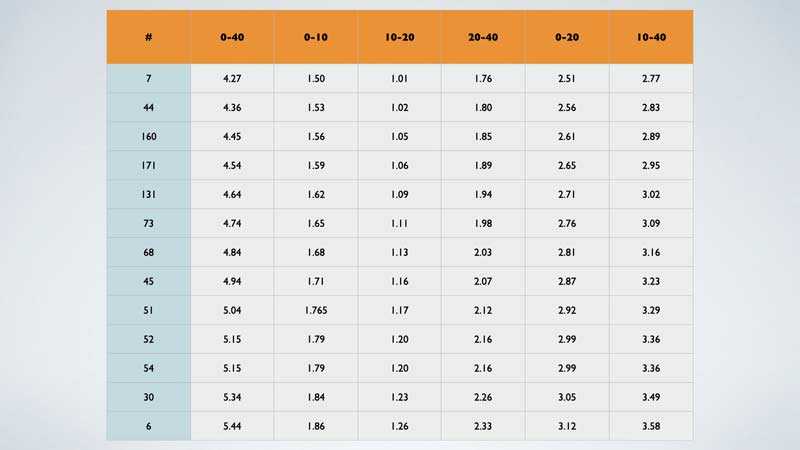

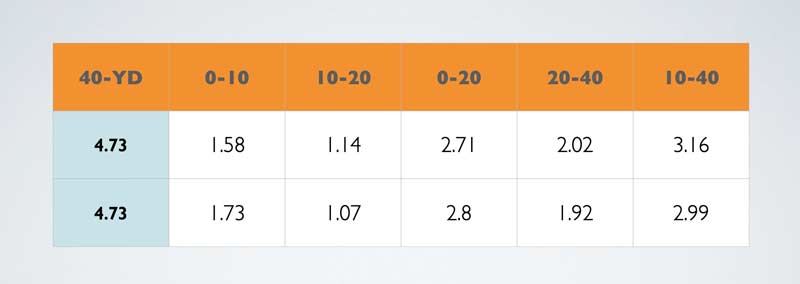

We did an evaluation of every single athlete who was trained in the building. Only after the athlete had earned a level of ability did we use the TENDO Unit. Today’s advancements, such as GPS tracking devices like Catapult Sports, provide a true objective measure for programming. Volume and intensity for team output and each athlete are objectively identified.

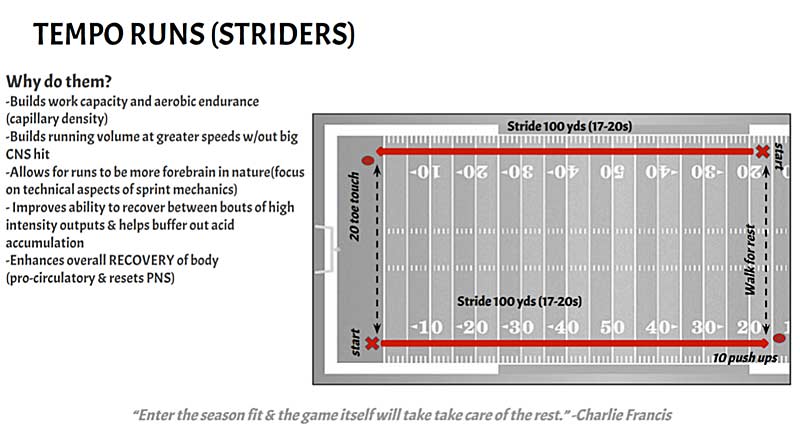

Many other components can also be identified such as number of IMAs (COD) along max velocity and high-speed yardage. This information allows us to program the speed at which a group of athletes runs tempos, ensuring they are specifically training the desired outcome.

Freelap USA: You are a licensed massage therapist as well, showing the value to you of soft tissue therapy. How have you seen your training reduce injuries, and how do you look at muscle status to facilitate those results?

Tim Rabas: The tissue quality of an athlete provides information about how the athlete is responding to our training. A mentor once said that if you want to have longevity in this profession, get access to a quality manual therapist.

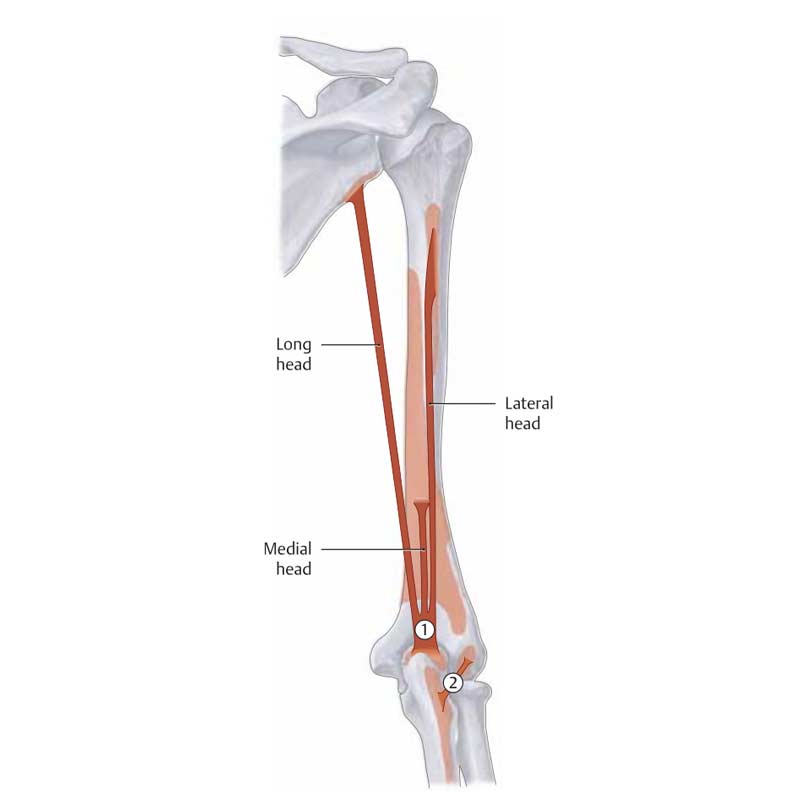

Muscle tone provides information about the movement patterns of the athlete. We all have asymmetries, and this is a predictor of injury. Share on XMuscle tone provides information about the movement patterns of the athlete. We all have asymmetries, and this is a predictor of injury. Identify and strategize to address the deficiency. We can discover adhesions/scarring of damaged tissues in certain locations in the body, particularly the hamstring, quads, and IT bands. Lastly, muscle tone indicates our level of hydration and how well we can clear byproducts of training (lactic acid). These three areas have absolutely helped minimize the likelihood of injuries.

Freelap USA: The process of challenging and stressing an athlete requires careful record-keeping to be safe yet aggressive. When reviewing workouts, what do you do to enhance your system for next year? What does this method look like?

Tim Rabas: Having a collaborative relationship between the sport coaching staff and athletic training is critical. Collaboration shows that the departments want to foster a relationship to learn and develop creative solutions that benefit the athlete. Each year has a new challenge. We always reevaluate and determine a few new objectives for the next training cycle.

A young team may focus on reestablishing work capacity and refining movement techniques. Developing that athlete requires a balanced approach to maximize the power-to-weight ratio. The consideration of body weight for setting standards of performance is another lesson I learned under the tutelage of Al Vermeil and his staff. A 300-pound lineman benching 1.25% body weight should be able to complete a few pull-ups. The emphasis is always directed toward what is lacking.

Freelap USA: Data without leadership is just a chart with a doomed forecast. How do you see coaching integrity succeed with transparency? When communicating with team coaches, how can high performance work more collaboratively so an athlete can truly evolve better?

Tim Rabas: Assumptions are dangerous in any area of life. Data should be checked and cross-checked prior to making a forecast to any member of an organization. It is better to deliver small accurate bits of information that can be understood clearly. Making an inaccurate claim runs the risk of losing trust.

It’s always best to do the homework on the front end and educate the group that you will be communicating with on what information will be provided. There will be times when the suggestions you make will go against what a coach wants to do. Be courageous and deliver the information and provide a hypothesis of concerns based on the objective data you hold. Be consistent and offer suggestions for a creative solution.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF