To be, or not to be, a multisport athlete—that is the question.

The answer? Like so many other things, it depends.

I’ve found that coaches encourage athletes to play multiple sports to improve overall athleticism and fill buckets of performance that they may not tap into within their “main” sport. Unfortunately, this virtuous and well-intended idea has, in practice, become riddled with little-to-no context, poor application, and limited transferability, making “multisport athlete” yet another buzzword in the sports performance industry.

While most (if not all) coaches understand the importance that different performance qualities ultimately play across the variety of sports, positions, and playing styles athletes are exposed to, the execution on the coaches’ end is lacking—particularly when it comes to track and field directly translating to and improving other court and field sports.

As a former athlete and current coach, having dealt with the supposed performance pipeline of football players running track to get better at football (primarily wide receivers, running backs, and defensive backs), I’m not seeing that realistically play out in real time. At least not on a large (or large enough) scale to justify the hard push.

If the only goals of pushing field and court sport athletes to run track are to improve speed and provide a source of off-season competition, but the means of doing so come at the cost of the athletes:

- Enjoying themselves

- Understanding the context

- Neglecting, or even damaging, physical traits crucial for their primary sport

…Then what’s the point?

In this article, I will counter the idea that football players, and any other field or court sport athletes, need to join the track team in the off-season to improve their performance on the field and/or court.

*Disclaimer: Track and field is one of my favorite sports to watch, and the primary reason I watch the Summer Olympics.

Definitions

Sport: “Any form of competitive physical activity or game that aims to use, maintain, or improve physical ability and skills…” – Wikipedia

Athleticism: “The physical qualities that are characteristic of athletes, such as strength, fitness, and agility.” – Dictionary.com

An understanding of these two definitions should start to clarify the issues with pushing track as a team-sport performance enhancer to all other sports and reveal the path to a clearer solution.

In the game of football, the qualities, skills, and abilities include—but are not limited to—speed (linear and multidirectional); agility; power; strength; “physicality” (for lack of a better term); and a basic understanding of game rules, techniques, and tactics (i.e., blocking, tackling, catching).

Track and field requires and builds speed, speed endurance, and power, and in a best-case scenario, it promotes efficient sprint mechanics. This is not a slight.

Speed and power are important qualities in American football. Speed and power are also important qualities in track and field. These are things we know and understand.

However, the issue arises when track is used as a tool to enhance speed and/or power for a sport with minimal relation to track performance.

As a coach (former track and field, current football, and strength and conditioning for multiple others), I’ve seen just about every version of high school athlete participate in track because:

- They were trying to get better for another sport (a noble venture).

- It’s “easy.”

- Their friends begged them to.

Out of all of the athletes I’ve had the opportunity to work with, only a handful actually reaped benefits that were transferable to another sport. Were there improvements? Absolutely. Did these improvements show up in another arena? Seldom. Football players who ran track in the spring and then came back out for football in the summer were visibly more efficient in their running and sprinting, but often lacked control in deceleration, game agility, and change of direction ability.

Enjoyment = Improvement

There is an abundance of information and research available that shows physical activity (and sport participation) improves the mental and emotional health of children (and adults). But what if the individual doesn’t enjoy the activity they’re participating in?

It is my belief (because of science) that when sport is truly enjoyed, there is a dopamine spike and “higher levels of dopamine can lead to feelings of euphoria, bliss, and enhanced motivation and concentration.”1

Enhanced motivation and concentration, in turn, will lead to greater bouts of effort, which will then eventually lead to improvement.

That being said, I believe the inverse to be true as well. When sport and physical activity is not truly enjoyed, there is no release of dopamine, leading to a lack of motivation and concentration.

Track practice is like no other sport practice I know of: There are very specific skills, traits, and qualities being honed, and at times, it can be pretty tough both physically and mentally. With a lack of motivation, those practices and often mundane activities can grow old fast for a youth athlete, and it can be a monumental task for coaches to keep their undivided attention. Especially these days, when research shows that on average, “children ages 8-12 in the United States spend 4-6 hours a day watching or using screens and teens spend up to 9 hours.”2

Forcing or manipulating an individual to participate in any activity removes the enjoyment from it and leads to a decreased probability of any optimal benefit coming from that participation. Share on XForcing or manipulating an individual to participate in an activity removes the enjoyment from it and leads to a decreased probability of any optimal benefit coming from that participation.

Context Is Key

Football players need—and should want—to get faster and more “explosive.” In between whistles, football is a high-intensity, fast-paced game that the longer you play, year to year, the faster and more explosive it gets. There are, however, varying types of speed.

There is speed-ability (how fast you are physically capable of moving through space) and then there is speed-skill (also commonly known as game speed).

In his book, Game Changer, Fergus Connolly discusses the “Four-Coactive Model” for performance: physical, technical, tactical, and psychological. For the purpose of this article, as it relates to football, I believe psycho-physical, and techni-tactical should be joined as such.

Racing against either an opponent or the clock is in no way the same as running even one play on the football field. The physiological demands of both activities are similar, but not nearly identical. We can make the same comparison between the training of change of direction and agility. While the basic fundamentals of the simplest aspect of each have overlapping points, their functionality and execution are separate existences.

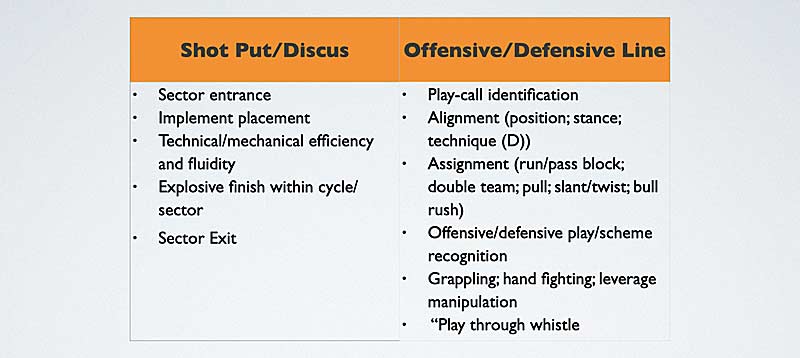

Below, I have created tables of the most comparable activities/positions between football and track and field to visually represent what each takes to perform effectively.

Again, this is a general overview of the events and activities stated, but as you can see, there are very few—if any—similarities in their execution.

Now, if we’re looking at specific qualities that track practice and meets can help to develop (i.e., acceleration, max velocity, “explosive power”), then yes, there are more similarities that can be matched up. But in regard to playing football, those similarities do not exist much outside of the first .5 seconds of any given play.

The speed ability that helps one excel, or even just survive, in a football game can be developed with the track and field program, but the game speed that is required cannot. The many variables of the techni-tactical type that are necessary for football players are specific to the game, development, and preparation process of football in and of itself.

The fastest athlete on the track in the 100m or 200m can be virtually nonexistent on the field as a wideout if he does not have: the appropriate knowledge of the game and his position; the ability to maneuver near, around, and sometimes through a defensive player; or the technical ability to catch a ball.

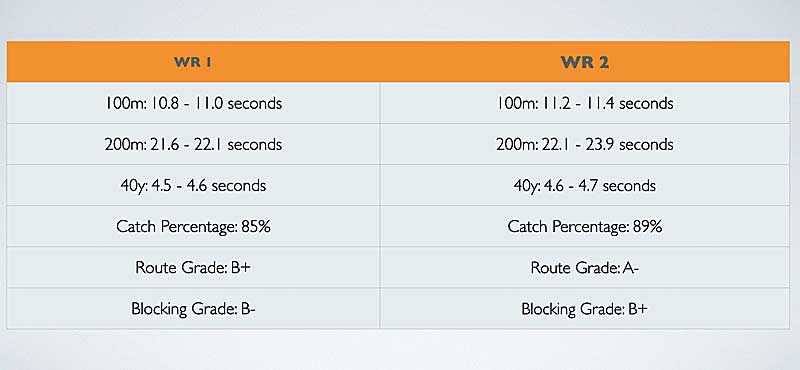

Let’s take two hypothetical wide receivers, and their (again, hypothetical) performance numbers:

It is safe to assume that WR1 would be the starter and/or primary receiving target and threat. While WR2 lacks “track speed” or the speed ability of WR1, based on these hypothetical numbers, he is the better technical football player: a better pass catcher, a better route runner, and a better blocker. That being said, he could most certainly benefit from speed training.

This speed training can come in the form of joining and competing on the track team—indoor and outdoor—in events that are directly related to acceleration and max velocity: 55-meter dash, 100-meter dash, 200-meter dash, and short sprint relays.

Other options, though, are a great strength and conditioning program offered via the sport coach, a strength and conditioning coach within the school’s athletic program, or privately in their community. (Not all high schools have a strength and conditioning coach on staff, but information is readily and plentifully available for sport coaches to do an effective job.) With these three options, the speed development program can be tailored specifically within the context of football.

While track is the primary option for speed improvement—as running faster is the sole task for a number of events—it is not the only option, says @KoachGreen_. Share on XWhile track is the primary option for speed improvement—as running faster is the sole task for a number of events—it is not the only option.

I made a very similar, and admittedly less intelligible, point on Twitter.

Track doesn’t make you a better football player.

Being good at football makes you a better football player.

The “guys excelling at football because of track” rhetoric is a lie.

They excel at both because they’re good athletes.

@KoachGreen_

April 14, 2021

Needless to say, this tweet initially didn’t go over so well with a few track and field coaches and enthusiasts, as well as a surprising amount of current and former football players and coaches.

After the Internet dust had settled and discussions and deeper conversations were had amongst those who opposed and those who agreed, there seemed to be a consensus that people understand this truth—a sport can only really be improved by engaging in the actions of that sport.

And without speculating, the initial outcry was brought out because:

- Track and field at the high school and collegiate level is “under attack,” since it’s not as big a player as football and basketball in the financial aspects of their institutions and athletic programs.

- Coaches and athletes directly and indirectly involved in track and field are doing their best to lift up the name of the sport and are encouraging as many people to be a part of it as possible.

- And unfortunately, there is a small but effective set of individuals who are taking full advantage of the “speed kills” push happening in the sports performance industry.

In doing so, there has been a naturally developing narrative that:

In-Season Football Player + Off-Season Track participation = Better In-Season Football Player

Unfortunately, the equation is one of physics and sports science, not simple arithmetic.

Skills Pay the Bills

As defined earlier, athleticism is “physical qualities… such as strength, fitness, and agility.” We can throw speed and power in with those qualities because that’s what they are: physiological attributes that can be trained and adapted.

But those athletic qualities do not guarantee success in sport.

While track and field can aid in the improvement of speed development and running economy, it does not account for agility, physical interactive play with the opposition, opponent reactivity, decision-making, techni-tactical skills, and the bioenergetics necessary.

This is not to say one sport is better or easier than the other. Both are difficult in their own right. And I could argue that track may be more difficult.

The point is, individual sports are different, require their own individual training protocols, and cannot be used exclusively for the improvement of another.

The point is, individual sports are different, require their own individual training protocols, and cannot be used exclusively for the improvement of another, says @KoachGreen_. Share on XA young wide receiver who joins the track team after his freshman year in high school with hopes of improving his speed can be assisted in that endeavor—with appropriate coaching and guidance of course—but may still be terrible if he returns in the fall and cannot block, run a route, or catch sufficiently.

A lineman who joins the track team to throw shot and/or discus to improve his footwork and power may acquire a good glide/kick step for pass blocking and a decent “punch,” but the amount of strength and force-absorbing abilities he needs to actually stay in a pass set with a rusher, or just run block in general, may still be lacking.

A great track program can yield an average (or in some cases, worse) football player. A great football program can yield a below-average wrestler. Sports are not connected in the way people advertise them. They are interconnected by qualities:

- Speed

- Power

- Strength

- Agility

- Etc.

The presence of these qualities, in and of themselves, will not and has never made any single person better at a technically inclined sport. Instead, what these qualities do is create better athletes who, with appropriate preparation tactically, technically, and psychologically, can utilize them to be better in a sport.

They create an advantage. But advantages alone are useless if used inefficiently. Remember David and Goliath?

In conclusion, if the aim is to improve in the sport of football, the best way to do so is by playing and practicing football. If the goal is to improve the qualities that are intertwined within the sport of football (i.e., speed and power), then track can be the best option if, like every other sport, competent, qualified coaches are at the helm.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Eske, J. “Dopamine vs. serotonin: Similarities, differences, and relationship.” Medical News Today. August 19, 2019. Retrieved April 18, 2021, from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/326090#relationship

2. AACAP. “Screen Time and Children.” American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. February 2020. Retrieved April 18, 2021, from https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Children-And-Watching-TV-054.aspx.

I would agree, and say that the same is true for a S&C program. It will improve certain qualities and create adaptions but will not necessarily create a better sport player. That happens when those adaptions are used and improved by practicing the specific sport with a good coach.