I had the privilege of speaking to Kebba Tolbert (the associate head coach of women’s sprints & hurdles, and horizontal jumps at Harvard University) several times last season. While we mostly talked about in-season training and recovery, in previous interviews and in programs he created (Complete Track and Field: Specific Endurance for Sprints & Hurdles: An Advanced Approach), he has often stated the importance of building a base of speed and power in the off-season. In an interview with Latif Thomas last year, Tolbert said: “I would say (of) building the base (that) you want to build a base of speed and power and technical capacity, because technique matters, too—that allows you to perform at a high level consistently. So the base is really important, but the base is not aerobic.”

I’m not reinventing the wheel when I emphasize building a base of speed and #power, but it works, says @mario_gomez81. Share on XCertainly, we are not reinventing the wheel and writing about a paradigm shift in training. Obviously, coaches borrow freely from each other and, in this instance, I have borrowed many of the training ideas from Coach Tolbert and numerous others. I would like to discuss what building a base of speed and power looks like, and how it impacts your training cycles.

Training Week

When a training program makes speed and power a priority during the preparation phase of training, what does a typical week look like? What those three training days entail is completely a coaching decision. Below I discuss two different examples showing how we have included three days of prioritizing speed and power development.

General Prep: Example Training Cycle #1

This is probably the most traditional training cycle that we have followed early in the training year. We dedicate one day, usually Monday, to acceleration (between six and 12 starts). Early in the season we do starts from different positions (2/3/4 point). We generally start at 10 meters and work toward 30 meters, but rarely go beyond 20 or 25 meters because most high school athletes cannot accelerate properly.

At times, we create an acceleration complex or cluster (different exercises or drills to accomplish the same feeling) where an athlete pushes a hurdle, sled, or another athlete in order to feel how violent and explosive acceleration must be. Then, the athlete comes back and performs an acceleration without any physical restriction.

Later in the season, as we get closer to competition or testing, athletes start to use spikes and sprint on the track. We begin to compete against each other and practice acceleration during relay exchanges, and athletes begin using blocks if the coaching staff feels they are prepared.

Our second day is also dedicated to accelerations in several formats (pushing up a hill, pulling sleds with a harness, pushing when pulling is not an option, using bands, and any type of starts that you can imagine); anything that requires the athlete to create energy from a still position. We supplement acceleration training with horizontal jumps (standing long jump, standing triple) and horizontal bounding (skips for distance) and/or med balls throws that include a horizontal displacement. Again, as the season progresses, we begin to get more specific, as noted on Day 1.

Day 3 is another specific speed day. There is an unlimited amount of variation for what this day can look like, but early in the season we work on feel, technique, and the part-whole-part process (an idea stolen from Latif). Last season, I fell in love with the idea of straight leg bounds and used it as a primary exercise for developing elasticity. Again, I borrowed that directly from Coach Tolbert’s Specific Endurance training (which he, in turn, borrowed from Tony Wells). Our third speed session of the week might therefore have a max velocity warm-up (including max velocity sprint drills), wickets, and straight leg bound training modality, finished with another form of vertical displacement exercise to match the theme of the day.

What Should You Do Between Each Speed Day?

If we follow the format above in a seven-day cycle, what do the days between speed training include? At the high school level, most athletes do not train on Saturdays during the general prep phase. If we include three days of speed work in a five-day cycle, we might be asking for an injury and CNS fatigue. Therefore, we combine both acceleration days, and come back on Tuesday with tempo work (during general prep) to prepare the body for specific work later in the season.

We use Wednesday as a recovery day—a complete day off. Thursday would count as the second speed day and would look very much like Day 3 as described above. Friday would then be treated as a second tempo day to prepare the body for specific endurance later in the training cycle. If Saturday is available for training, then Friday could be a third speed day, followed by tempo on Saturday.

General Prep: Example Training Cycle #2

The following example will also look at training during the general prep phase. The three days of speed and power development remain the same—however, the daily order changes. It actually allows for a specific day within a seven-day training cycle, aside from three days of speed and power development. I came up with this weekly cycle training regimen from speaking with Gabe Sanders (the assistant coach of sprints and hurdles at Stanford University). Latif Thomas also talked about it in similar terms on Complete Track and Field.

Potentiation is the driving factor for Day 1. Basically, Day 1 prepares the body for Day 2, allowing for two consecutive speed days. Generally, speed days are separated by a minimum of 48 hours so the central nervous system can recover from all the power output created in a typical speed session and then come back 48 to 72 hours later to perform another speed session. Because Day 1 serves as a primer, the athlete will be prepared to have another valuable speed day of training the following day. Since high school athletes do not produce nearly the same amount of force as college or elite athletes, two consecutive speed days is safe for most high school athletes if the right exercises and progressions are followed.

Two consecutive speed days is safe for most high school athletes if the right exercises are done, says @mario_gomez81. Share on XDay 1/2 exercises can include any tools within the acceleration and max velocity inventory, keeping in mind the goals of Day 2. Both days can serve as acceleration or max velocity days, or a combination of the two. Latif Thomas talked about “training deeper in the same pool”—meaning using back-to-back days of the same skill—but using a variety of different exercises, versus “training shallower in the same pool”—meaning using one day as a more difficult version—but still training the same skill or speed in general.

Day 3 of speed would occur 48 hours later, on Thursday, allowing the body to recover following two back-to-back days of speed. During the general prep session, we give the athletes a complete day off on Wednesday.

Day 4 (third speed workout) would resume the work established during days 1 and 2. The athlete can revisit what was practiced or established in the first two days or complete a more specific workout.

For example, on Day 1 of this week I might have a 100/110 hurdler work on such things as skip for distance, pull a sled with a harness, or use a bullet belt or resistance band, all to apply the principles of acceleration. Day 2 might include wickets, following a max velocity warm-up and sprint drills. Then they would have Day 3 off. On Day 4, the athlete could come back and work over hurdle 1, if they are prepared to do so, or continue to work on the acceleration mechanics necessary to arrive at hurdle 1 in eight steps with proper mechanics. Depending on the skill level of the hurdler, they would then continue to the subsequent hurdles.

Another example could include a sprinter on back-to-back max velocity days working step over runs (dribbles) and sprint posture on Day 1, followed by performing wicket runs and fly runs on Day 2. Day 3 would be off and Day 4 could be another sprint-specific day.

Day 5 would follow Day 3 in that they would have the entire day off for prescribed rest and recovery. On Day 6, the athlete can complete their tempo runs to work on specific endurance, preceded by a tempo warm-up that also includes wicket runs or some sort of speed work.

Gratitude and Justification

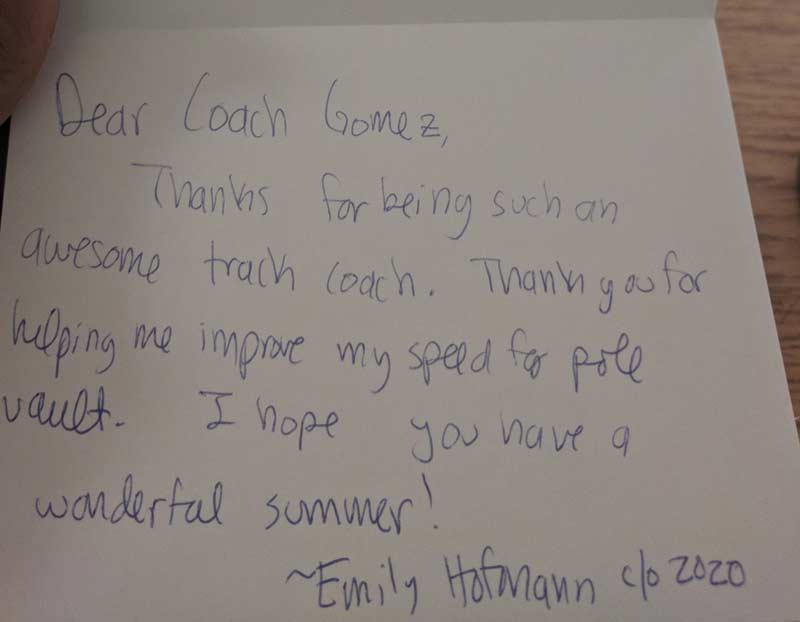

Our No. 1 priority as a program is to create speed, power, and coordination because the skills apply to the majority of events in track and field. At the end of last season, I had a pole vaulter write me a personal note before her family moved due to her father’s relocation. In the note, she stated, “Thank you for helping me improve my speed for pole vault.” I’m proud to share this letter because it supports our program’s emphasis on speed and power development, and how it translates to so many events.

We prioritize creating speed, power and coordination—skills that apply to most track & field events, says @mario_gomez81. Share on X

To reemphasize, this type of programming is certainly not new, but it is a training principle that I have come across in the last few seasons. It has allowed our programming to continue to focus on our No. 1 goal: Make athletes faster and more powerful. And if we focus on creating a base of speed and power in the off-season and throughout the general prep portion of the season, then our ultimate goal will certainly be closer to becoming reality.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

What days would you incorporate weight room? And how would your in-season track/ weight room days look?