Before training their athletes, the first thing a performance coach should do is engage in a detailed needs analysis. Look at the individual, their position, their sport, their playing style, and more. If you are still running cookie-cutter programs, then stop. Yes, I know it’s hard if you have 40 athletes to one coach, but you can still find ways to add individualized tweaks here and there.

Regardless of the planning methodology you choose, you still need to decide on your “big rocks.” These can be tangible or intangible qualities and skills. Here are some common “big rocks” in successful programs:

- Sprinting

- Jumping

- Medicine ball throws

- Zone 2 (aerobic work)

- General strength training

A good way to view this “big rocks” theory is to visualize an empty jar. To fill it, you have rocks, gravel, and sand. You could add all the sand first, then the gravel, and finish with the rocks—but you quickly can see that this is not the most optimal way to fill the jar. If you begin by putting your rocks in first, then the gravel, and then the sand, you will see how the cracks start getting filled in. Likewise, once you have your training mainstays, then you can start filling in the gaps.

Having constants in your program is also a great opportunity to allow athletes to ‘self-audit.’ Share on XHaving constants in your program is also a great opportunity to allow athletes to “self-audit.” Bondarchuk used to have athletes pick a handful of their favorite movements and then they would primarily train those. His throwers could then gauge effectiveness by the daily throwing they did—if he had them continually changing up exercises, it would be very difficult to pinpoint what worked and what didn’t.

Sure, elite athletes can be fast adapters, but you need time to stabilize and actualize the adaptations. Find the backbones of your program and use them as checkpoints to revisit and evaluate training. Boo Schexnayder has also talked about this concept in the form of “home base training”: If an exercise is important to the training program, it should exist in some form or fashion throughout the year.

This leads me to what I believe should be the backbones of every team sport athlete’s training program: tempo and chin-ups. Depending on the training block, coaches may get away from these to drive specific adaptations. After these periods, I would return back to your home base training and stabilize any residual effects.

Tempo Training

Tempo training traditionally has been done as a submaximal sprint effort. In sports that require high speeds and dynamic movement, coaches tend to only focus on the speed side of training. It is easy to fall into the speed trap because it is such an important quality for successful athletes to have. The old adage “speed kills” will live on.

My perspective has changed drastically on the subject. I started talking with other coaches and consuming any information on the aerobic system that I could. My main takeaway: Don’t sleep on the aerobic system for team sport athletes. Without a well-built aerobic base, it won’t matter how fast your athletes are. They won’t be able to repeat the same maximal efforts throughout the entire competition.

Without a well-built aerobic base, it won’t matter how fast your athletes are. They won’t be able to repeat the same maximal efforts throughout the entire competition. Share on XNot to mention the growing research into acute-to-chronic ratios in player loading. Without accumulation of work to match what they experience in their sport, the incidence of injury begins to rise. Common sense will tell you that the preseason is the time when the most soft-tissue, non-contact injuries occur. Why build a big engine on a frame that can’t handle it?

I could pose the question: Why does a track athlete need an aerobic base? They might only do a few max efforts and have very long rest periods in between. Charlie Francis and many other track coaches still trained athletes in a polarized program. On one end, athletes trained in the alactic environment. If you increase top speed, you also increase the speed of all submaximal efforts below that.

To contrast that, you use slow and smooth stuff. I’m sure Ben Johnson did some form of tempo, and it wasn’t all max effort squats and bench press to complement his high-speed track work. Tempo training might be the best bang for your buck—you develop the oxidative capacities of relevant musculature while having the opportunity to zero in on the technical aspects of running.

Talking with one of my mentors, it makes sense that tempo comes in two forms: energy system development and recovery. You could also say intensive and extensive, but I find that terminology tends to confuse more than it helps.

Energy system development is exactly what it sounds like. I want to train the body both centrally and peripherally to better utilize oxygen, take in nutrients, and shuttle out accumulated metabolites. This type of training widens the pyramid of performance. Theoretically, not only do you have increased capacity for repeated bouts, but you can also recover from them more quickly. In contests that last several hours, this is crucial.

Tempo training in this fashion can be in a variety of movements. Examples are linear tempo runs, curvilinear, submaximal change of direction, medicine ball tempo, strength aerobic resistance training, etc. Tempo can be done on grass, turf, a bike, battle ropes, or a rower, in a pool, or using strength training equipment.

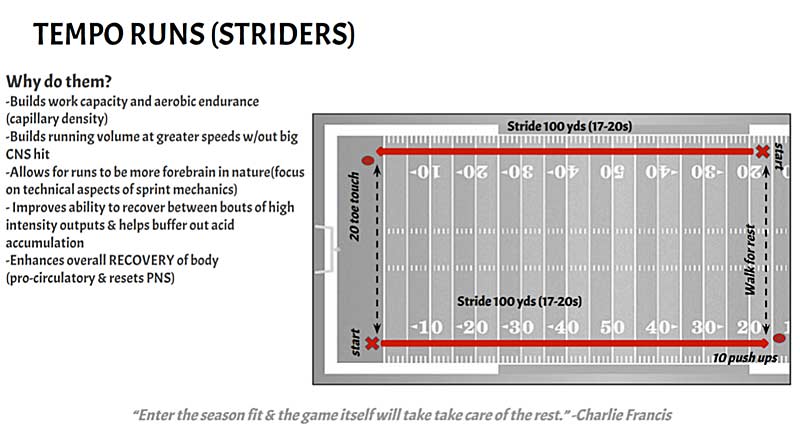

For team sport athletes, I reccomend performing tempo runs on grass. Doing your best to adhere to dynamic correspondence is key in training programs. Ultimately, the goal is to train just below your lactate threshold (~2.00 mmol). The benefit of tempo is that it substitutes for any long, steady-state cardio. You get better quality runs at faster speeds.

The benefit of tempo is that it substitutes for any long, steady-state cardio. You get better quality runs at fast speeds. Share on XBelow are two ways to use tempo runs for energy system development:

- 2 x 10 x 100 yards at 55%-60% of best time (add in BW exercises or MB work in between reps)

- Submaximal position work (wide receivers)

- Jog route tree x 20s/40s (progress to 40s/20s)

The more I look at tempo, the less I would have athletes go much beyond 65% into intensive work. It is hard to know exactly what lactate levels are during training (unless you are having them take samples.) That’s why a good dialogue with athletes is necessary. If the goal is to stay high-low and not interfere with my high output days, then it doesn’t make sense to constantly train there. As you progress closer to the season, one of your “high days” can mimic intensive tempo but focus more on lactic power and capacity.

Yardages are another focus point. Derek Hansen wrote an article years ago that has good recommendations for tempo volumes. I used to think they were a bit high, but looking back now, I’d agree that if you can get up to those weekly numbers, you are in a good spot.

The second form of tempo training is a primer for recovery. This style of training can improve circulatory mechanisms and reset muscle tone following competition or heavy resistance training. If you consistently trained tempo all year, then it could act as a “flush” to help the athlete return to a homeostatic balance. The intensity would fall on the lower end, around 50% of their best time.

RPE (rate of perceived exertion) can be used also—I like to see athletes in the 5-6 range on a scale of 1-10. The talk test is a simple way to gauge the intensity: You should be able to talk while performing movements.

I like the zone 2 parameters that Peter Attia has talked about in many of his podcasts. Zone 2 is an endurance athlete training scale popularized in cycling. Zone 2 is basically training at the highest outputs possible while staying below your lactate threshold. Adaptations occur mainly in the type I fibers where mitochondrial density is usually higher.

At any given time, athletes should perform three sessions at 60 minutes or four sessions at 45 minutes (at least three hours per week). Zone 2 tempo is steady state in nature. If using heart rate (HR), a quick way to determine working HR is the MAF 180 formula. Basically, it is 180 minus your age. You can adjust based on limitations or other lifestyle factors (+/-10 beats).

Whether to drive adaptation or to recover between contests, tempo is a great way to audit the readiness of athletes. Say you work in the NFL or at a lower division collegiate program. In these situations, chances are you won’t get to see your athletes for any extended period of time. Tempo would be an effective way to have a “progressing” conditioning test working in the background. If you know that an athlete needs to complete X amount of work to be ready, then you can direct training approaches to help bridge the gap. You can also pulse tempo (use roughly a third of off-season running volumes) throughout the in-season period to drive recovery from performances.

Whether to drive adaptation or to recover between contests, tempo is a great way to audit the readiness of athletes. Share on XI could write an entire article about how alactic efforts are impacted by improvements in the aerobic system, specifically in the capacity to repeat high intensity outputs. In a true high-low model of training, finding ways to be as polarized as possible would allow you to both “raise the floor” and “push the ceiling.”

The Chin-Up

Athletes require certain technical, tactical, physiological, and psychological attributes in order to have successful outcomes. In team sports, the bulk of work done is through cyclical and acyclical movements. So, you might ask yourself, why then are chin-ups a backbone in a program? The answer lies in relative strength and mass specific forces. (Disclaimer: Obviously, positions where athletes tend to weigh more and require higher strength levels will not always fall under this category. Remember, context is key.)

Good coaching is trial and error. What got me to point A won’t necessarily be what gets me to point B. To break through to something, you must break from something else. Experienced coaches have noticed that their faster athletes are typically also solid at performing chin-ups. You can get into the claim that a chin-up trains shoulder extension similarly to that of the arm action, but not here. It’s all about mass specific force.

Another argument is that if being good at chin-ups correlates to faster running speeds, then gymnasts would be excellent 100m sprinters. This is not the case. Don’t mistake correlation with causation. The scope of this article is to identify the backbones of training. These are things we can use to audit our programs for future course correction.

Back to the chin-up. It makes sense that athletes with lighter body weights could theoretically do more chin-ups; but without the requisite strength, they could also be poor at them. Looking further, fast sprinting requires you to produce high levels of force in decreasing increments of time relative to your body mass. In track and field sprinters, maintaining a lean body weight is beneficial since extra mass will likely slow you down.

Well-known coaches like Barry Ross and Ryan Flaherty recognized this in their practices. In Ross’s case, he trained exercises that would stimulate the nervous system while minimizing tissue damage and hypertrophy. A deadlift that eliminates the eccentric portion of the lift is a popular example of this style of training.

Bodyweight training is another way to accomplish this, whether it is from plyometrics or calisthenics. The goal is to produce as much force as possible at the lightest body weight to play your sport. Aside from the musculature involved during a chin-up, it is a good choice to assess relative upper body strength. If your athlete can do them, do them. I believe it’s worth the investment to train some variation of chin-ups at all times of the year. Handling your body weight is a must for any athlete. Chin-up for reps or weighted chins are a simple, cost-effective way to build athlete standards throughout your training system.

I believe it’s worth the investment to train some variation of chin-ups at all times of the year. Handling your body weight is a must for any athlete. Share on XLet’s look at different ways you can progress chin-ups based on your athlete population. Regardless of the sport, if your athlete can’t do a dead hang chin-up, then take a step back. Below is a progression that you can use to get that first chin-up:

- Inverted BW rows (work to 15-20 reps in each category and add in sets)

- Legs bent

- Legs straight

- Legs elevated

- Weighted

- Chin-up iso, top position (work up to 90 seconds)

- Work passive hang also (2 minutes from bar)

- Eccentric chin-up (work up to 45 seconds of work)

- 8 x 5 second lower and use box/bench to reset

- Chin-up

- Weighted chin-up

The above progression is adaptable for females and males at any age level. I typically won’t program more than 50 reps of chin-ups per session. Start adding in extra weight once body weight becomes easy. There will be some outliers who need special programming, such as larger athletes and longer-limbed athletes.

For American football linemen, if they can’t perform them, I usually piece together a few exercises: passive hang, close grip lat pulldown (underhand grip), and incline TRX BW row are my main choices. The goal is still to get chin-ups, so sometimes I might have them loop a band on the rack to add assistance to the reps.

For long-limbed athletes like basketball players, I’ve successfully done the above progression. I added in some wide grip lat pulldowns to target the lats and help build the supportive musculature. Based on what you see as a coach, you can manipulate the exercise choice and sequencing to fit your goals.

The big coaching points with the chin-up are:

- Extend the arms all the way out at the bottom of each rep.

- Pull the elbows down and back on the concentric action.

Strong Opinions, Loosely Held

The backbone of your training program could be any KPI you want. At the end of the day, you need to know your population. Tempo training and chin-ups are two choices that can span all athlete qualifications. Get really good at them, then work to fill in the gaps elsewhere.

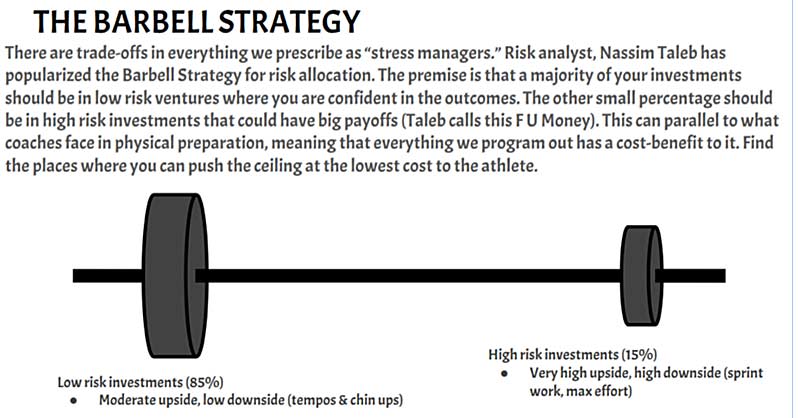

The backbone of your training program could be any KPI you want. At the end of the day, you need to know your population. Share on XExpanding this thought out further, tempos and chin-ups are low-risk investments that have a good chance of yielding positive returns. Nassim Taleb, a financial risk analyst, uses a model called “The Barbell Strategy.” On one end of the bar, you have low-risk investments that are in a way safe. On the other end, you have the high-risk investments that have much greater downsides. This small allocation of funds allows for aggressive tactics to be used in hopes for a very high upside.

Taleb talks about a general distribution of 85% low-risk to 15% high-risk (similar to the distribution of the Pareto Principle). Tempos and chin-ups are exercises with little downside and moderate-high upside. Your true speed work and maximal effort lifts are across the spectrum and should be used intelligently.

The profession has gone away from simplicity. As coaches, we are support staff. What you do will not win games (though it might lose some). Accept that, drop your ego, and start searching for the “best” answers. The greatest thing you can do is to have strong opinions that are loosely held. Always be willing to change and adapt while you continue to learn.

The greatest thing you can do is to have strong opinions that are loosely held. Always be willing to change and adapt while you continue to learn. Share on XI am the first one to speak out against stating anything in absolutes. Often, it is smart to disregard the content and further investigate the context. The human body is complex. There are too many variables at play for anyone to say they know for sure where their athletes will be even a day from now. I would love to implement some things I see out there on social media, but 30 minutes with beat-up athletes changes a lot. Most days it turns into running around with an index card, going from plan B to plan C to plan D—and having those backbone exercises to fall back on keeps things in place.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF