With the football season wrapped-up, prospects, whether they have aspirations of a college scholarship or hearing their name called on draft night, are turning their attention to speed. It is no secret that one of the best ways to improve your stock as a prospect is by improving your time in the 40-yard dash. While most coaches know a good time when they see one, many struggle to actually make their athletes faster.

I was in that same boat, but I wanted more. I wanted ways to analyze the data from my athletes and make better training decisions from that data. After taking a deep dive into the times of NFL draftees over the last five years, I have found a few trends that can hopefully help guide you on your quest for improved speed. After reading, you will have a better understanding of the intricacies of this highly valued sprint and be better able to help your athletes achieve their speed goals.

Before we begin, understand that the times being discussed are solely from the NFL Scouting Combine. All reps were run in Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis using Zybek timing systems. The times we see published publicly are started by hand with gates at 10, 20, and 40 yards. Zybek does compile FAT data that is not shared with the public, but they did explain on Twitter that: “If the coach is at the 6 yard line, the average [difference between human vs. FAT] is 0.085 [seconds]; however, there is a +/- 0.05 seconds or larger (1 Standard [Deviation]) in the best case.”

The Three-Second Rule

In the last five Combines, 376 draftees ran sub-4.6 seconds; 365 (97%) ran the “flying 30” portion in 3.00 seconds or less. For the high school athletes I coach, we use the 30-yard fly as our primary max velocity metric because I love how seamlessly it ties in with our 40-yard dash training. For most high school speedsters, running a 30-yard fly in three seconds or less is not a daunting task, but when you reduce their run-in, the task becomes more difficult and aligns with the acceleration needed to master the 40-yard dash.

It is important to know the difference between ‘how fast can you get?’ and ‘how fast can you get fast?’, says @CoachStokowski. Share on XIt is important to know the difference between “how fast can you get?” and “how fast can you get fast?” Once you understand the speed strengths and weaknesses of your athletes, you can narrow your training focus to address those needs. Cameron Josse comes to mind when I think of using pragmatic exercise selection to address needs on the force-velocity curve.

Big Fellas Need a Good Start

One of my favorite metrics to play around with is pounds-per-inch: a way of analyzing relative size and the speed needed for success at that size. Athletes at 4.0 pounds-per-inch or larger dominate in the trenches of professional football. We are talking about body sizes ranging (on the small end) from 72 inches, 293 pounds (4.07 pounds-per-inch) to 79 inches, 317 pounds (4.01 pounds-per-inch).

One-hundred sixty-nine athletes 4.0 pounds-per-inch or larger have been drafted since 2016. Twenty-two of them (13%) were able to crack five seconds in the 40-yard dash. When looking at the splits from those attempts, I notice a distinct difference between the speed profiles of professional linemen and high school skill players. Running similar 40-yard dash times, the linemen excelled in the acceleration portion (0-20 yards), while the novice high schoolers fared better on the back end (20-40 yards).

Taking a closer look at those 22 linemen, their times ranged from 4.75-4.99. On average, their front 20 yards clocked in at 2.85, while their back 20 came in at 2.06. None of those 169 draftees, other than Caleb Benenoch (his published splits point to a possible error at the second gate), were able to break 2.00 seconds from 20-40 yards. On the flip side, I have recorded 119 40s between 4.75 and 4.99 from my high school athletes, obviously much smaller clientele. Their average front/back split is 2.86/2.02, which does not seem like much of a difference, but 38 (32%) of those ran sub-2.00 on the back 20 yards.

Two takeaways:

- Once a body gets to a certain size, there is not as much velocity potential. In other words, linemen at the Combine do not have the maximum velocity ability to outrun a slow start. They MUST get through 20 yards fast (relatively) to finish fast.

- When a high schooler legitimately lowers their time by a significant amount, the area of most improvement happens early in the dash. Does an improved maximum velocity help? Absolutely! But never forget that around one-third of your time happens over one-fourth of the distance.

Apples, Oranges, and Doughnuts

When discussing the 40-yard dash, it is important to remember that the gold standard, the NFL Scouting Combine, is more concerned with consistency than accuracy. We know this because both FAT and hand-started times are recorded, but the hand-started times are the ones shared with the public.

The goal of recreating exact testing variables is a fool’s errand, but there is value in attempting to find a level of consistency and accuracy in your testing protocol. Surface, shoes, weather, and a myriad of other nuances make the way you time the 40-yard dash unique. I believe we should all try to create a testing protocol that provides an in-depth look at our athletes’ abilities and gives us information on where our time would be best spent in their training. In classroom terms, I believe we should be using the 40-yard dash as a formative assessment as well as a summative one.

I know the way I time (apples) is not the way the NFL does (oranges), but both do a good job of providing feedback. Simply telling an athlete that they ran “4.4” (doughnuts) is not true (99% of the time) and does not provide them with the information needed to improve their speed. Sure, it makes them feel good, but it does not make them better. By providing split times within the 40-yard dash, we can learn far more about our athletes’ strengths and weaknesses.

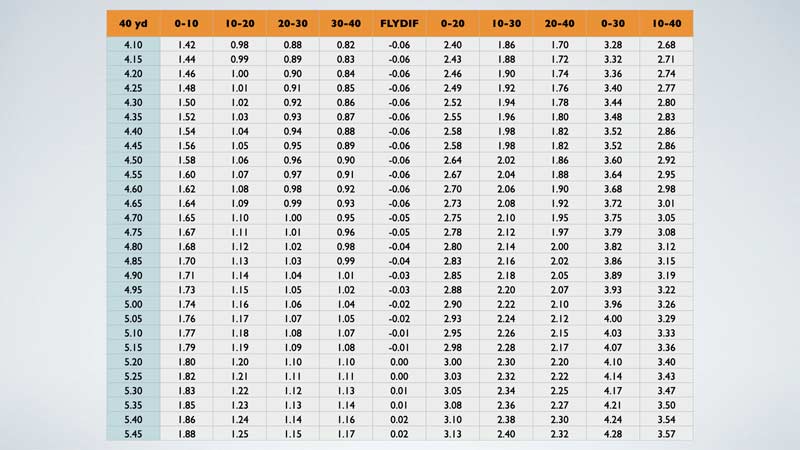

By providing split times within the 40-yard dash, we can learn far more about our athletes’ strengths and weaknesses, says @CoachStokowski. Share on XI use Freelap to time the 40-yard dash, on a rubberized track wearing spikes. We use the touchpad as a consistent way to tether our athletes to a moment of near-zero forward momentum. We place split transmitters (cones) at 10 yards + 80 centimeters, 20 yards + 80 centimeters, 30 yards + 80 centimeters, and 40 yards + 80 centimeters. (For those unfamiliar with Freelap, 80 centimeters accounts for the radius of the electromagnetic field produced by the transmitters.) By setting up the system the way I have explained, we acquire 10 pieces of data from one single attempt: 0-10 yards, 10-20, 20-30, 30-40, 0-20, 10-30, 20-40, 0-30, 10-40, and 0-40.

In my three years timing athletes using Freelap, I have had two athletes break 4.70 seconds. Coincidentally, those are the only two skill players who have been offered any form of NCAA Division I football scholarship. With that knowledge, we know running in the 4.6s, using our metric, has value.

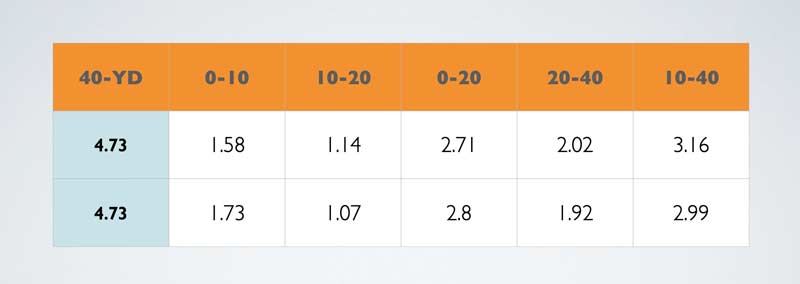

Our favorite two segments to analyze are 0-20 and 10-40, and the formula for success is simple: 2.70 seconds from 0-20 yards and 3.00 seconds from 10-40 yards. If the athlete can find just one-hundredth of a second, they break 4.70.

Two seasons ago, I had two athletes run 4.73 on the same day. Athlete A ran 2.71 from 0-20 and 3.16 from 0-40. Athlete B ran 2.80 from 0-20 and 2.99 from 10-40. Identical outcomes with significantly different speed profiles! Athlete A needed maximum velocity intervention while Athlete B had significant room to improve on his acceleration.

Need for Speed

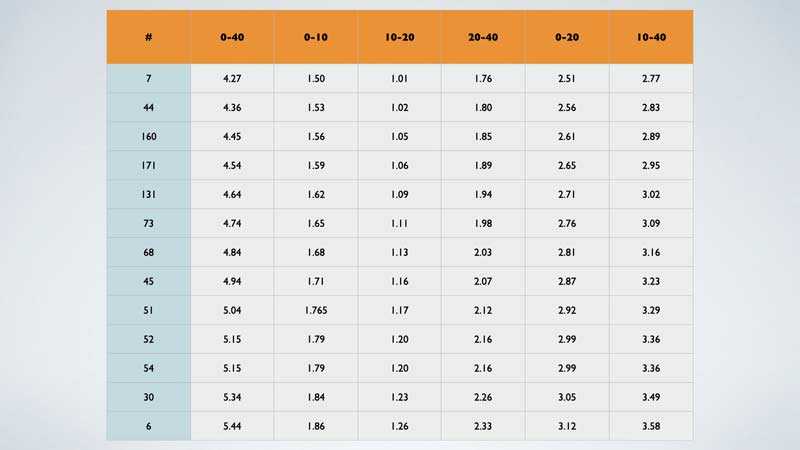

Using mph as an easy-to-understand metric for young athletes is all the rage. I am on that bandwagon, and I wanted to know what kind of speeds we are seeing from the elite athletes at the NFLSC.

Here is a breakdown of the “flying 20-yard” portion of the 40-yard dash. We are looking at average time, pounds-per-inch, and mph of draftees since 2016. Keep in mind that the Vmax numbers are faster than I will show, since the athletes, for the most part, are faster at yard 40 than yard 21. Also, be careful comparing turf times with limited run-in to track times with unlimited run-in.

- 2 (3 total); average: 4.26 seconds; pounds-per-inch: 2.74; flying 20: 1.76 = 23.24 mph

- 3 (43 total); average: 4.36 seconds; pounds-per-inch: 2.77; flying 20: 1.80 = 22.73 mph

- 4 (159 total); average: 4.45 seconds; pounds-per-inch: 2.87; flying 20: 1.85 = 22.11 mph

- 5 (171 total); average: 4.54 seconds; pounds-per-inch: 2.97; flying 20: 1.89 = 21.65 mph

- 6 (131 total); average: 4.64 seconds; pounds-per-inch: 3.13; flying 20: 1.94 = 21.09 mph

- 7 (73 total); average: 4.74 seconds; pounds-per-inch: 3.29; flying 20: 1.98 = 20.66 mph

- 8 (68 total); average: 4.84 seconds; pounds-per-inch: 3.44; flying 20: 2.03 = 20.15 mph

- 9 (45 total); average: 4.94 seconds; pounds-per-inch: 3.72; flying 20: 2.07 = 19.76 mph

- 0 (51 total); average: 5.04 seconds; pounds-per-inch: 3.98; flying 20: 2.12 = 19.30 mph

- 1 (52 total); average: 5.15 seconds; pounds-per-inch: 4.11; flying 20: 2.16 = 18.94 mph

- 2 (54 total); average: 5.24 seconds; pounds-per-inch: 4.08; flying 20: 2.21 = 18.51 mph

- 3 (30 total); average: 5.34 seconds; pounds-per-inch: 4.13; flying 20: 2.26 = 18.10 mph

- 4 (6 total); average: 5.44 seconds; pounds-per-inch: 4.19; flying 20: 2.33 = 17.56 mph

- 5 (7 total); average: 5.55 seconds; pounds-per-inch: 4.18; flying 20: 2.37 = 17.26 mph

In conclusion, I hope that this information will help you better understand the data on your athletes, and, in turn, you will be able to provide them with better feedback and training. While not every athlete we coach will reach their speed goals, you will see improvements in team speed if you keep it a focus of your programming. The 40-yard dash is a puzzle, but one that reaps massive rewards when mastered. I hope this resource helps you better understand the pieces of that puzzle!

If you would like to talk shop or have any questions, do not hesitate to reach out to me at [email protected].

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Good article coach. My 5’9 205 pound running back son graduates high school soon and will be playing NAIA D2 football in Fall 2021.

I have digitally hand timed him at 4.72. What specific drills do you recommend we use to improve upon his time? He is fairly quick.

Thanks

I’m just a reader and football fan, but from what I understand of the article, it would be a good idea to time his 0-20 split and 10-40 split and compare them. A 1.5 seconds seems to be the high end of speed for the 0-10 split, so for example: if he runs a 1.68 second 0-10 split you would want him to practice running that split and try to edge his time as low as possible, improving his acceleration and thus his overall 40 time. If he’s already close to 1.5 or feels he is as fast as he can get in the 0-10 split, then you would try… something else, maybe adjust stride length or run style? Sorry, the article didn’t go into that much detail. Hope that’s helpful, good luck to you and your son!

I did 2 splits of throwing baseball out the blocks .1.7 & 1.7. While running 🏃total 3.44 111ft.

SuperMan 🏃🏈

How do you set up the timing on the freelap app for timing 40 and splits

Place the start cone at 1 yard and the finish cone at 40 yards 31 inches.