Good ol’ warm-ups! When you hear the term “warm-up,” I’m sure a few different things come to mind: running slow laps, static stretching, mobility circuits, mini-bands, movement drills, and so on. For as long as I can remember, I have participated in “dynamic warm-ups”—all the way from Little League through my days playing college football. All of them had a common outcome: They were anything but dynamic and didn’t move the needle in terms of accomplishing the goal of “warming us up.” (Looking back, this has become even more clear.)

For as long as I can remember, I participated in “dynamic warm-ups”—they were anything but dynamic and didn’t move the needle in terms of meeting the goal of “warming us up,” says @bigk28. Share on XEven when I began leading my own warm-ups as a professional, we still weren’t accomplishing what was necessary or maximizing our time. That’s why this year I got rid of the term “warm-up” and swapped it out with “ignition series.” Our ignition series has two primary goals:

- Improve performance

- Ready the athlete for the activity ahead

In this article, I outline what I use as our current ignition series and what you can do to get the most out of your pre-practice, pre-game, or pre-lift routine. I changed the name of “warm-ups” to “ignition series” to make it clear to my athletes that we were no longer going through the motions or easing into things—we were sparking our nervous systems to perform at a high level.

Warm-Ups, Then and Now

In Little League, our coach would have us run around the field, do jumping jacks, and stretch our hamstrings (sadly enough, this is still common among teams across all levels). Fast forward to high school football, when my fellow captains and I were responsible for leading the team in a pre-practice/pre-game “warm-up.” We used to stand on the goal line and lead the team through a series of static stretches, both upper and lower body, before we went into team drills.

In college, we came out in different groups based on position, going through different “movement drills” before partnering up to do static stretches and then moving on to position-specific drills. Through the years, each warm-up became a little more complicated, but still didn’t accomplish what was necessary during a pre-practice/-game routine. The only good thing I took away from doing these warm-ups—through all my years of playing—is that when I finally did design my own warm-up, I didn’t want static stretching anywhere near it.

The only good thing I took away from doing these warm-ups through all my years of playing is that when I finally did design my own warm-up, I didn’t want static stretching anywhere near it. Share on XCoaches can debate all they want about whether static stretching helps an athlete get prepared or present the argument that “the athletes like it”—in my opinion, that’s an insufficient argument. Our job as professionals is to give athletes the best possible recipe for success, and sometimes that’s things they may not enjoy…AT FIRST. But I guarantee if you implement the series I outline below, the athletes will feel better in movements that matter (such as speed).

As a professional, my warm-ups evolved over time into the sequence I had run through the past couple of years:

- Jump rope circuit to increase blood flow

- Foam roll series on the now pliable muscles

- Different “glute activation” drills before going into the weight room

Initially, for a warm-up before a run or practice, we spent our time going through “dynamic movements” followed by “form running” drills that were anything but dynamic and did nothing to improve form. Looking back, I’m glad I led these warm-ups just to know exactly how much we were wasting our time (or doing activities with less-than-optimal intensity).

Ignition Series

The moment I decided to change our pre-activity routine came when evaluating how effective our warm-ups were—I can honestly say that they were uninspiring and did nothing to prepare the body for what was ahead. When jumping rope, it appeared more like a chore than a preparation. Our foam roll series looked like a pillow session, with athletes just lounging on the foam rolls versus performing the drills with 100% focus. The mini-band series, which was probably our most engaging of the three-part warm-up, would turn into a friendly talk session for the entirety of the rep/set scheme.

Until the day I changed my warm-up, I saw too many athletes go through the motions during this period. If you want to improve at anything, you must do it with 100% effort and intensity. I was failing them as a coach: If these were things that I wasn’t inspired to do before my own workouts, why should they feel any differently? This becomes even more true when going through a warm-up before an intense activity.

Before I go into our current warm-up, it is important to understand how much time we spend on our “warm-up” throughout the year. I personally do not see my athletes daily, and most of the time they do their warm-ups on their own. I wish it could be different, but this is the truth of the matter, and I must optimize how much time I have with them and take into consideration how much time they are completing this series without me.

Let me break the math down for you. We are currently in week 23 of our training year for both of our men’s and women’s basketball teams. On average, we lift 2-3 times a week, they practice 4 times a week, and they play games twice a week (regular season). On days we plan on lifting, we do our ignition series first, so we get the most out of the lift. I would say our warm-up takes roughly 15 minutes. Here is the math for how much time we spend warming up throughout this period:

- 15 minutes a day x 6 days a week = 90 minutes

- 90 minutes x 23 weeks = 2,070 minutes = 35 hours

On the days my athletes are with me, we usually do our ignition series for 15 minutes, followed by a 45-minute lift. I will go over our lifting in another article, but let’s look at those numbers. Based on how long our lift sessions are (1 hour), those are 35 extra 1-hour sessions we get in during this period with just our ignition series alone! I know a lot of coaches say the warm-up is so important, but how many of those coaches spend time doing knee hugs and Frankenstein kicks? Last time I checked, the knee-hug lunge won’t move the needle in terms of improving sports performance.

Below, I outline the four parts of our ignition series that help our athletes improve performance throughout the entire year. One of the best lines I’ve heard about sport performance is (and I paraphrase)—If it doesn’t look like their sport, then it isn’t improving performance. I have used that principle in developing this warm-up to make sure we are doing what’s right by the athlete to maximize their genetic potential.

1. Reflexive Performance Reset™(RPR)

There are few things that have been more influential in my career and had a bigger impact on my athletes then Reflexive Performance Reset™ (RPR). I have never come across a system that prepares my athletes and ensures correct firing patterns better than RPR. Throw away your glute bridges and lateral banded walks and go learn about the Reflexive Performance Reset™ system.

I am not going to go into the extensive aspects of RPR (you can look that up on your own), but since implementing RPR we have seen a reduction in injuries and games lost due to injury. This is consistent among all teams that use RPR within our program. No, I’m not arbitrarily saying this—I have the data and the facts to back it up. (If interested, get a hold of me and I will share those numbers.)

Injuries are going to happen, but it is our job as professionals to reduce the risk. RPR helps reduce that risk. We start with belly breathing for a minute in a supine position, our zone 1 warm-up for about 30 seconds each zone, and finish with supine belly breathing for another minute. We perform assessments on our athletes prior to the year, so if any athlete has any incorrect or less optimal firing patterns, we give them additional drills to correct those firing patterns before we begin our workout.

The beauty of RPR is that you can always adjust on the fly. If an athlete comes in and they are feeling less then optimal, there are drills you can use to help their CNS fire the correct way. The other beautiful thing about RPR is that the athletes can do it on their own; they don’t need a coach there to tell them the drills or to perform the drills on them. The system is incredible! Seriously, if you have not taken an RPR class yet, go and do it—it will be one of the best things for your career and for your athletes. After performing RPR we are ready to start our next set of drills.

2. Sprint Mechanics

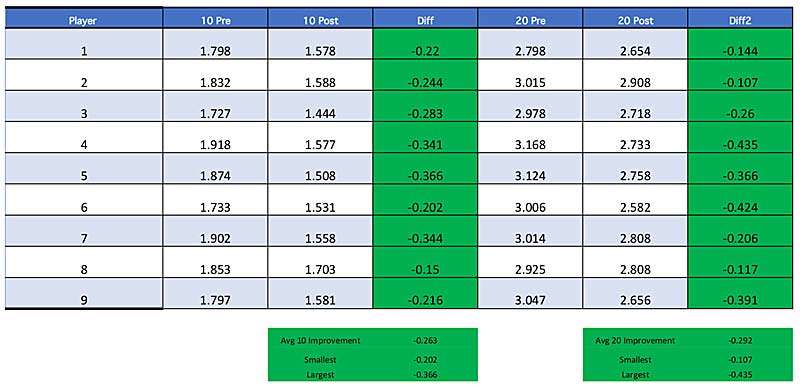

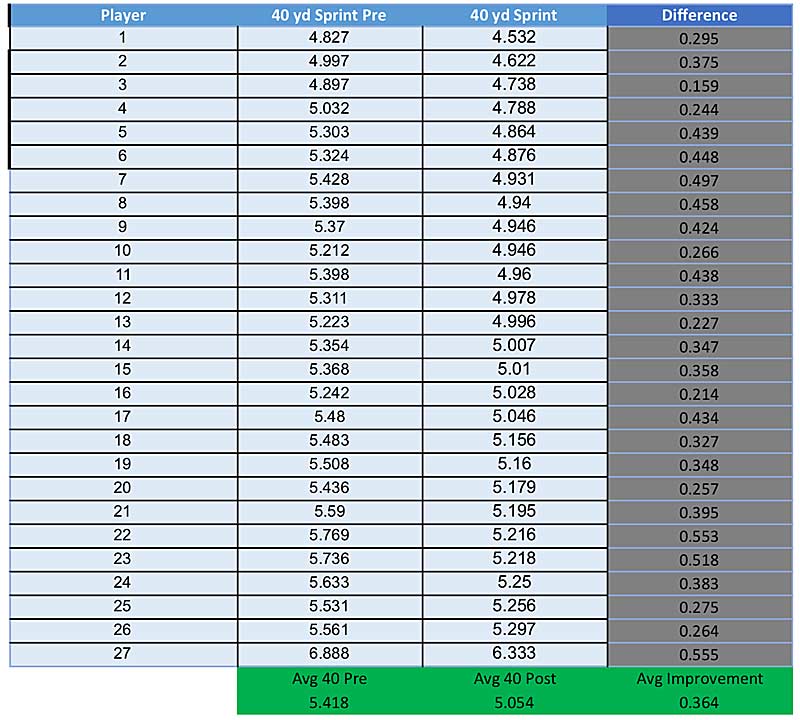

This is not going to be a section on how to make Olympic track athletes, but rather simple things I have implemented that have helped my athletes improve their technique and therefore their speed. I experimented this year with ONLY doing timed sprints prior to our lift, and I got good results. I saw improvements in sprint times throughout the entire year just by doing 10-/20-yard sprint variations. Just because something works, however, doesn’t mean it is ideal.

I have read a lot of articles about whether altering sprint mechanics has an impact in the field of play or during competition. The answer I have found out is simple: YES. A lot of athletes just do not know how to run, and it is our job as professionals to do the best we can to help correct easy mistakes. We do not all have to be track coaches or speed gurus to see that athletes are at risk of injuring themselves when running out of control at high speeds.

I have read a lot of articles about whether altering sprint mechanics has an impact in the field of play or during competition. The answer I have found out is simple: YES, says @bigk28. Share on XThese are the sprint mechanic drills we perform daily. All of them are done at 100% effort followed by 100% recovery. Each athlete should do these at their own pace; we do not need everyone to do the drill at the same time to look like a “team.” Performing drills as a team to look unified is a gimmick. We need the drills to be effective at improving performance, and that means each athlete doing the drills at their own pace when they feel recovered. The following is a list of drills we do daily:

- A/B Skip Variations (march, low, regular)

- High Knees with correct arm action

- Butt Kicks (real ones)

- Ankling Drills

- Bounding Variations (speed, height, straight leg, single leg)

- Backward Runs

Insert Video 1. Athletes in the gym performing sprint mechanics and mobility drills as part of the “Ignition Series.”

We do the first four variations one time through over the distance of 10 yards. We do bounding and backward runs once or twice (depending on the day) over a 20-yard distance. All these drills are designed to excite the CNS and improve speed. The day after a game, these drills change slightly; we usually cut the volume in half in terms of distance and increase the recovery between each drill. I can tell you that athletes will be prepared to run fast year-round, as I have seen many kids PR even after playing 40-60 minutes of high-intensity athletic events.

Now that I have outlined the drills that we use in order to improve our sprint mechanics, there are also simple form cues I follow when looking at improving speed:

- Triple Extension out of the Start: For any sport where an athlete starts in a two-point stance (lacrosse/softball to name a few), it is crucial to look to see if they get proper triple extension. Way too many athletes come stumbling out of their stance, false stepping with their necks extended, chest forward, and big knee drive from the front leg. All big no-no’s when it comes to proper starts.

- Relaxed upper body and face: This one I see way too often—an athlete trying to run faster, so they hike their shoulders up, close their eyes, create tension in their face, and stiffen up every part of their upper body. This is a disaster for running effectively at high speed. I tell all my athletes to run relaxed, shoulders down, eyes open, moving smoothly. This is something we can improve upon instantly with regard to improving speed.

- Upright running motion: Simple, but athletes will lean forward while sprinting, lessening their knee drive, increasing the braking effect of their foot, and therefore slowing themselves down. Tell your athletes to get upright when sprinting in order to get maximum force production from their lower body.

- Arm drive: It is strange how athletes sometimes use (or don’t use) their arms in the course of sprinting. The cue I give, and I heard from Coach Tony Holler, was driving their elbows back so their hand passes their hip. This is another simple cue, but it must be hammered away when coaching sprinting mechanics. It may not dramatically change their speed, but anything that can help improve, we want to do.

If we do any of those movements listed before, we will lose force and be slower. We are looking for our athletes to be in a straight line with regard to their ankle, knee, hip, and shoulder (triple extension); this will be the best position to produce the most amount of force. When we get tall, we also get maximal stretch reflex of the hip flexor helping us to fire the front knee forward in our second step out of the gate. Our second step should work on keeping that foot as close to the ground as possible, shortening the distance to the second step. Again, I’m not saying this is perfect, but this is what has worked for my athletes. I found that athletes benefit most when you film their start so they can see what they are doing.

3. Timed Sprints

To me, this is the most important part of the ignition series. I know there is some controversy over the issue, but in my opinion, if you don’t have your athletes running timed sprints, you are not working on speed. It is not the fault of the athletes participating, but it is human nature. When you are being timed and the times are being announced, you will run faster.

I know there is some controversy over the issue, but if you don’t have your athletes running timed sprints, you are not working on speed, says @bigk28. Share on XI have experimented with thousands of athletes and my lightbulb moment (I have a few of these throughout the year) happened after an off-season with one of my teams. We worked on “speed” every Monday before our lifts. We did progressive sprinting movements (or, at least, I thought we did), from bodyweight to hills to bands and sleds. After 14 weeks of training, I couldn’t have been more excited to test their sprint times. Shockingly, my athletes made little improvement. Looking back, it was very clear why they didn’t improve: They weren’t being timed. When you are asked to full-out sprint and you go 90%, that is not enough to improve speed. WE MUST RUN WITH 100% INTENSITY.

I have spent six years at my current school, and I have seen more improvements in speed in the last two semesters then in my previous five years as a coach. Timed sprints work and help improve speed. There are some variations of timed sprints we do as the final part of our warm-up:

Each drill is performed 2-3 times, depending on athletes’ results:

-

- 10-Yard Sprints

- 20-Yard sprints

- Flying Sprints

- Sled Drag Resisted Sprints

- Sled Pushing Resisted Sprints

- Wickets

- 40-Yard Sprints

Like I said earlier in the article, I did nothing but 10-yard and 20-yard sprint variations in the fall and saw great improvements in our 40-yard dash times across all sports. Over the course of this year, my mind has shifted, and I am now putting a bigger emphasis on developing max velocity.

I believe if our max velocity improves, so will our acceleration. I saw someone say that it is ill-advised to have your athletes jump right into 40-yard sprints without properly working them up to that intensity and distance. I will have to respectfully disagree for one reason: There is no time for preparation when you get to college.

If you play a fall sport, you get to campus in July/August, and as soon as you get on the field, you will be competing in practices and sprinting distances of 40 yards and more. You will not sit out because you don’t have proper mechanics, and you will not sit out because you haven’t run all summer. You will be in the middle of high-intensity practices, competing for a spot. That’s why, as sports performance coaches, we need to prepare our athletes for the rigors of competition, each day.

Evaluate Your Own Warm-Up

In closing, if you still find yourself doing “warm-ups” that include slow movements and less-than-inspiring drills, you need to start evaluating what it is you want to accomplish. As a sports performance coach, I would love to see my athletes as often as possible throughout the week. But, based on your situation, that may not be a reality, and you need to figure out the next best thing to helping your athletes daily.

The days of looking at the warm-up as just a thing we need to do before we work out are behind us, and we need to start looking at it as a great amount of time we get to improve performance. Share on XBy looking at some of the steps mentioned above, you can create your own plan that is best-suited for your athletes. I think the days of looking at the warm-up as just a thing we need to do before we work out are behind us, and we need to start looking at it as a great amount of time we get to improve performance. So, ditch the warm-up, and start igniting your athletes to get the most out of their training every single day.