[mashshare]

Long-term athletic development (LTAD) is “habitual development of ‘athleticism’ over time to improve health and fitness, enhance physical performance, reduce the relative risk of injury, and develop the confidence and competence of all youth.” Many groups and organizations have espoused the implementation of LTAD, such as Canadian Sport for Life, the USOC, and the NSCA.

LTAD and quality coaching are both part of the process of positive youth development. LTAD is a framework, not specific directions for unknowing coaches to follow. The framework is important because it:

- Identifies that there is a problem with how adults are providing quality experiences for kids.

- Shares evidence (both research-based and practical application) that the current youth sports system (fitness and physical activity, too) is flawed.

- Creates the structure with which youth practitioners can develop their system that works with the kids they coach, using the LTAD framework as a template.

Applying LTAD with Youth Tennis Players

My current sports environment provides the opportunity to train kids from 10-18 years old, primarily. They participate in one (or more) of three ways: summer sports camps, year-round sports programming, and fitness center usage. For example, they can sign up for tennis under USTA classifications for early development programs, which matches their playing ability, age, and tennis placement.

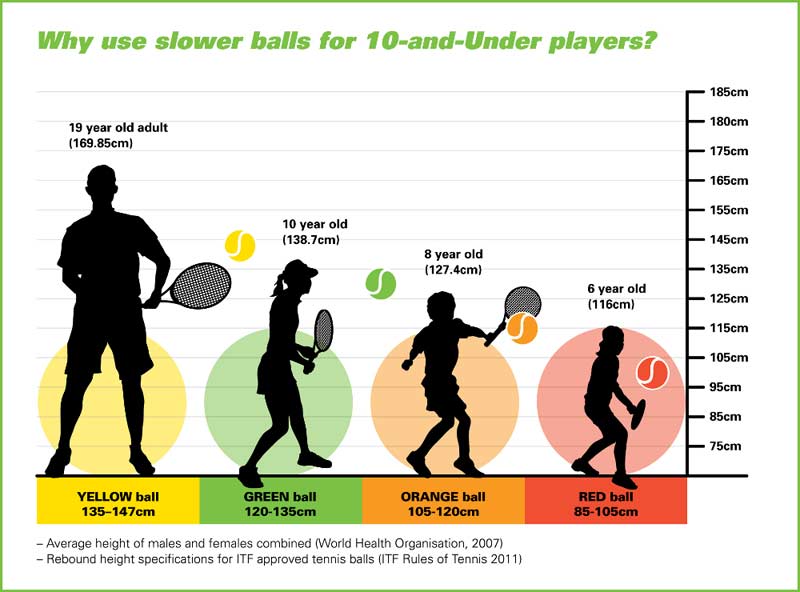

The club uses this model, which has a progression for the Junior Tennis Pathway that looks something like this:

- Munchkins: (3-4 y/o)

- Red: three levels (5-8 y/o)

- Orange: two levels (8-10 y/o)

- Green: two levels (10-12 y/o)

- Yellow: two levels (12+ y/o)

- High Performance/High School

The program is largely technical and tactical, and—according to USTA—seeks to get more kids playing tennis and kids playing more tennis. Luckily, the forward-thinking tennis staff believes in LTAD and expands the USTA concepts to allow me to integrate fitness training for all age levels during summer camps, and all year long before or after practice. This has helped the aspiring athletes make the connection between fitness and sport success, and learn to enjoy movement in other contexts.

I begin by teaching the ABCs of movement: athletic stance, body awareness, and cardinal planes of motion. No matter what sport the kids play, they need to know the universal athletic stance, and how moving their body, either with a racquet, lacrosse stick, or bat, changes their need to keep their balance over their base of support. Then we begin to move in all three planes of motion from the athletic stance. We learn this in a fun, informal environment with games, child-led or child-selected activities and challenges, and traditional exercises and sports skills.

Additionally, youth ages 10-15 can become Beasts! Using what they have learned in group sessions, they earn their Beast badge, which is the name they created (with multi-colored wristbands emblazoned with “Certified Beast” on them) to signify that they could now use the fitness center with their parents (10- and 11-year-olds) or on their own (12- to 15-year-olds). In this way, the youngsters are active all year, engaging in year-round free play, semi-structured play, and structured play. Many of these kids play school sports and/or other sports at the club, so an LTAD culture is developing and parents are seeing increases in both performance in sports and interest in fitness.

In our program, we focus on all 10 fitness attributes across three levels:

- Level 1

– Rules and etiquette

– Athletic stance

– Body awareness

– Cardinal planes of movement

– Instruction in exercise technique for a variety of movements

- Level 2

– Continued instruction in additional exercises

– How growth and development influence exercise selection

– PHV: pros and cons

– Training age

- Level 3

– How to design LTAD programs

– How to teach exercise technique to others

– Sport relevance

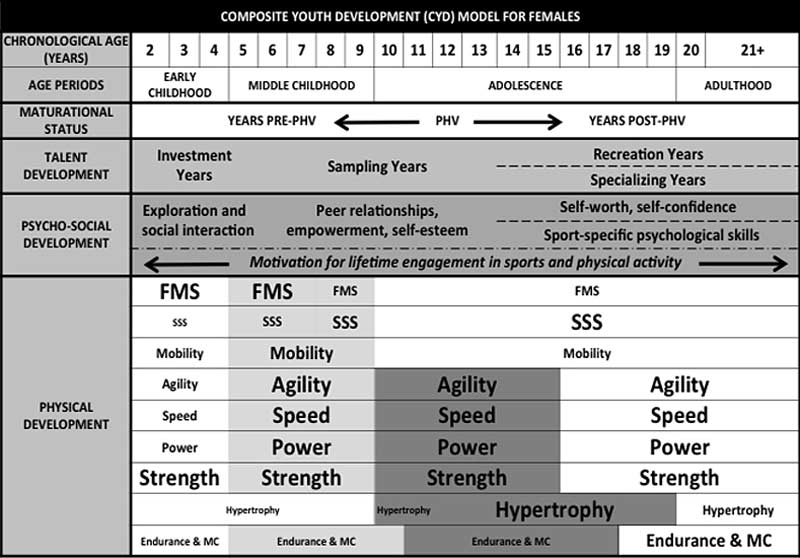

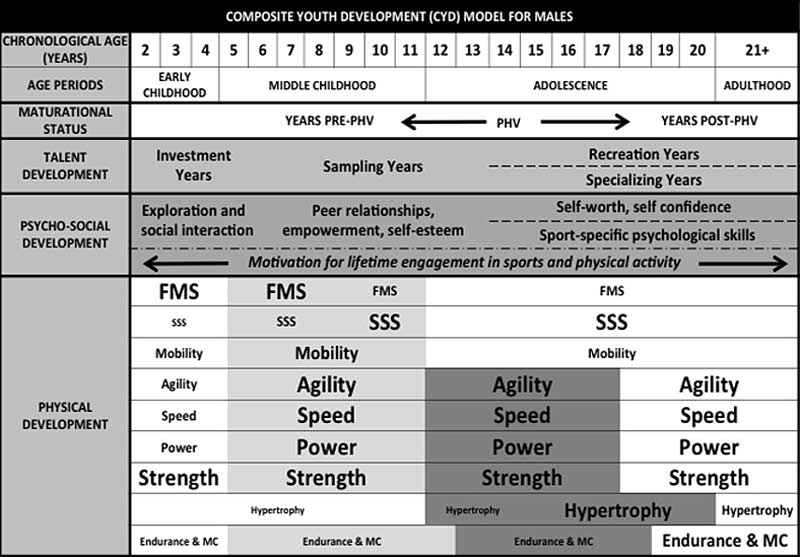

We continually train all 10 fitness attributes, in accordance with the Composite Youth Development Model from the NSCA LTAD Position Statement.

All fitness attributes are trained across childhood and adolescence. Our movement, skill, game, and sport application model affords us the flexibility to incorporate sport-relevant training for all kids, all the time. After only one year of implementation, we are finding that the youth in our program participate because they have fun, interact with their friends, and develop skills and strength. All these positive findings correspond with the top reasons kids play sports, indicating that we are not only developing their athleticism, but we are giving them ownership of the process so that it is their motivation to continue. This is key to promoting lifetime participation in physical activity.

Our program is in line with recommendations for all fitness attributes, including developing speed. Istvan Balyi’s LTAD model, modified by the United States Olympic Committee as the American Development Model, shows speed as having two specific “windows” in which it is thought to develop faster than in other periods. The first window is between ages 7 and 9 in boys and 6 and 8 in girls, and again from 13-16 in boys and 11-13 in girls.

The Youth Composite Development Models and the Unchained Fitness blog on “windows of opportunity” both indicate that any fitness attribute is largely trainable across childhood and adolescence. This means that youth sport coaches and strength and conditioning coaches should train all fitness attributes for all kids.

Youth sport and strength & conditioning coaches should train all fitness attributes for all kids, says @rihoward41. Share on XDue to the pillar that says that growth and development is nonlinear, it is difficult to establish when a “window” (“sensitive period” is thought to be a better term) exists. It is better to give every youth the opportunity to improve speed as well as every other fitness attribute (fundamental motor skills, sport-specific skills, mobility, agility, power, strength, hypertrophy, endurance, and metabolic conditioning) at all stages of growth and development for children and adolescents (roughly ages 6-19).

LTAD Foundations

Nonlinear growth and development of youth helps validate that kids are unique and different from one another—biologically, physically, and psychosocially. Therefore, it is impossible to say that all kids on a team should be doing a specific drill or exercise, or that a magic formula or gold standard applies. For these reasons, LTAD is a framework that was never intended to tell coaches specifically what to do. It is incumbent on coaches to learn as much as possible to better understand pediatric principles that can be applied to kids of varying levels and abilities.

The NSCA Long-Term Athletic Development Position Statement provides 10 pillars of LTAD, which can be summarized as:

- The health and well-being of all kids is the central tenet of LTAD.

- Development of fundamental motor skills and muscle strength are paramount to successful participation in sport, physical education, and physical activity.

- Kids should be routinely provided with opportunities to develop health-fitness and skills-fitness capacities across childhood and adolescence.

- Kids do not grow at the same rate and growth is not a linear progression.

- All kids deserve an opportunity to play, be active, and participate in sport at every age and ability.

- Kids should be exposed to a variety of sports, games, and physical activities (play, chores, etc.).

- While focusing on positive sports and physical activity, it is important to remember proper injury prevention protocols and practices for youth.

- Testing is only a snapshot of performance on that given day, so it must be used prudently when determining ability. Testing should reflect overall abilities.

- All kids should be introduced to strength and conditioning, which can be integrated into sports practice, so that they develop positive healthy habits, learn to enjoy strength and conditioning, and get in shape to play—not vice versa.

- Coaches need to understand pediatric principles of youth growth and development, including pedagogical instruction, to best serve youth.

You can see, therefore, that a coach cannot simply read the NSCA Long-Term Athletic Development Position Statement (or any other LTAD construct, for that matter) and expect to have ready-made practice plans for Monday afternoon! It should be obvious by now, however, that LTAD helps provide a reference point for what coaches need to do for all aspiring athletes. An athlete needs to be defined as anyone with a body; meaning that we work with kids of all ages and abilities, not just who we regard as elite athletes.

#LTAD helps provide a reference point for what coaches need to do for all aspiring athletes, says @rihoward41. Share on XIt has been suggested that “elite” is a word that should not apply in the world of youth sports, as so many growth and maturational influences can change the developmental outcome. Instead, focus on physical literacy. According to the International Physical Literacy Association, physical literacy “is the motivation, confidence, physical competence, knowledge and understanding to value and take responsibility for engagement in physical activities for life.” Therefore, as coaches we need to promote the value of sports as part of physical literacy, recognizing physical literacy as a key component of positive youth development.

When looking through the lens of positive youth development, it is extremely important for coaches to promote sports, play, and other physical activity. For example, the Ten Pillars of a Good Childhood recognizes the importance of play, physical activity, positive experiences, social interactions, and positive youth-supportive communities. If we believe that our current sports model does exactly that, then how do we explain that 70% of kids drop out of sport by age 13 and 25% of kids never play a sport? For comparison, video games are played by 97% of youth—is it because we have not created a youth-centric sports experience?

Similarly, the Search Institute’s 40 developmental assets for youth clearly indicates that the NSCA Position Statement pillar on the health and well-being of youth goes far beyond the physical component and includes the physical, social, and environmental well-being of youth. This should remind all coaches that sports and other forms of physical activity are one cog on the Wellness Wheel (for example, the William Diamond Middle School version).

It is important for all coaches to recognize their role in overall positive youth development, says @rihoward41. Share on XThe Wellness Wheel includes the physical domain, but also recognizes the importance of the social, emotional, environmental, intellectual, and spiritual domains. If any of the dimensions are undervalued or not included, the wheel is flat. It is important for all coaches to recognize their role in overall positive youth development, which is quite often promoted through sports and other physical activity.

LTAD Summit and Beyond

Despite the evidence for the 10 Pillars of LTAD, there continue to be coaches that think that LTAD is irrelevant and that LTAD is just coaching. Really? Then why are we still plagued with coaches that:

- Yell at kids.

- Play only the most talented kids.

- Overschedule games and under-schedule development.

- Use exercise as punishment.

- Have too much volume in their program.

- Use maximum lifting with kids that can’t properly perform the lift.

- Focus on the product of winning rather than the process of positive youth development.

- Use repetitive drills rather than create fun, game-type experiences.

- Think they are “dealing” with parents instead of engaging parents.

- Feel that their sport is the center of the universe, not the kids.

- Over-specialize kids too early.

- Do not focus on the whole child because they refuse to bridge the gap between science and practical application.

Even if they are volunteers, coaches should invest in their role by better understanding LTAD, to do the best job possible.

Check out opportunities for professional development within the sporting community and from other youth-serving organizations. Many National Governing Bodies (NGBs) of Olympic sports have developed implementation strategies specific to their sport. Many of these strategies are primarily technical and tactical, so there remains some work to be done on physical training, but there is information available. Coaching organizations such as the US Center for Coaching Excellence, USOC/Athlete-Development/Coaching-Education, National Alliance for Youth Sports, and Positive Coaching Alliance all have excellent materials for youth coaches.

A Long Term Athletic Development Summit was held in May to address the growing concern that youth sports are not youth-centric; that physical literacy, daily physical activity, and free play are being lost at the expense of overstructured sports; and that all youth practitioners and stakeholders need to be at the same table. Attendees included NGBs, the NSCA as a featured national organization, and local practitioners who came together to promote a grassroots “boots on the ground” implementation strategy for LTAD.

The structure was such that all attendees shared their experiences and strategies for implementing LTAD, provided input to one another at roundtables, and as a group, constructed feedback on sessions for direct application to practitioners. The day concluded with an accountability town hall exercise, where all attendees were asked what they would do to help bring LTAD to the population in their school, rec center, gym, community, etc. Accountability statements will be checked throughout the year and reviewed at next year’s session.

The summit enabled participants to not only share with one another, but to be part of the process of taking LTAD to the next level. Collaborations among participants to further the widespread implementation of LTAD are underway. LTAD Summits are being planned in other key locations throughout the coming year.

#LTAD is a vital framework to ensure all kids can grow, learn, and play to the best of their ability, says @rihoward41. Share on XWe need LTAD now more than ever. It is time to band together all positive youth development organizations and agencies to share the message that physical literacy through sports, play, and physical education is paramount to the growth and development of kids. LTAD is a vital framework to ensure that all kids can grow, learn, and play to the best of their ability, and that we as coaches, parents, and community stakeholders must make it happen. We need to act and increase accountability to make LTAD the focus of youth sports, physical education, physical activity, and play.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]