Managing training load has become an increasingly prevalent concern in athletics, for sport coaches as well as strength and conditioning coaches. I work with an NCAA volleyball team, and it is imperative to monitor and manage fatigue for a number of reasons: reducing injury risk; improving performance in general; specifically maximizing performance for key matches; and managing the overall readiness of each team member individually, as well as the team as a whole. Off-season training is different, but this article will discuss a method (and justifications) for measuring fatigue during the competitive sport season.

Addressing the Specific Demands of a Sport

Jumping is a critical movement in volleyball. Across practices, matches, and training, volleyball players jump more frequently than athletes of many other sports. Intense hops, bounds, and depth jumps require the highest nervous system demand and generally necessitate 2–3 days of recovery before training again.1 Unfortunately, college volleyball players are not afforded the luxury of taking 2–3 days off between practices, games, or strength and conditioning training sessions.

For volleyball, jump performance is a useful metric in helping coaches make adjustments to the training needs of the athletes, explains @will_ratelle. Share on XTracking fatigue—both acute and chronic—is important to training for the maximum performance at the critical time. For volleyball, jump performance is a useful metric in helping coaches make adjustments to the training needs of the athletes.

Constraints in Collegiate Sports Training Programs

Ideally, strength training would occur when an athlete is rested and recovered from practice or competition. NCAA sports, however, have unique circumstances that must be addressed when developing practice plans and training sessions. Every team must follow the same maximum practice/training hours rules per week, but each team will have different situations regarding:

- Practice time of the day

- Training time of the day

- Travel schedule

- Class schedules

- Age/gender of athletes

The volleyball team that I work with consists of 18- to 22-year-old females, with practice times at 6 a.m. Our weight room training sessions occur immediately after practice ends, with a 10-minutes transition period from the court into the weight room. Training after practice isn’t ideal, but it’s the time slot available. We share facilities with both the men’s and women’s basketball teams, so we all have to work together to get our practices and training sessions in.

The team travels at inconvenient times, sometimes early in the morning or late at night, and sometimes they’ll be out of town for as much as six consecutive days. Every college student athlete has to go to class, and some have more rigorous class schedules and workloads than others. There are 15 players on the volleyball team, and there are many factors that cannot be controlled that may or may not impact their performance.

How to Use Squat Jumps to Measure Fatigue

Our program measures three squat jumps at the beginning of each conditioning training session using the Just Jump Mats. A squat jump is defined as a vertical jump at a self-selected depth without a counter movement. The athlete gets into a jumping stance, drops into a self-selected squat depth, holds for a count of “one one-thousand two,” and then jumps from that position without dipping down again. A squat jump height is usually lower than a countermovement jump.2

Video 1. A single squat jump performed from self-selected squat depth and using proper form.

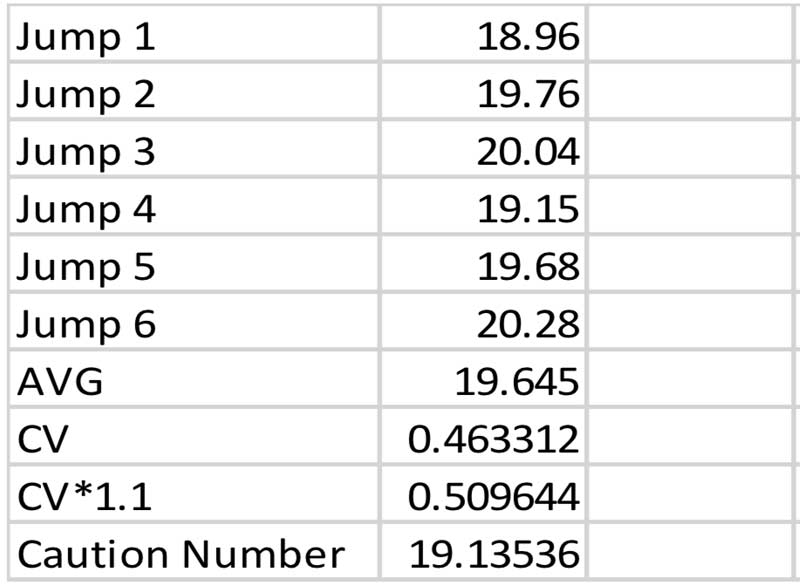

We have our baseline jump height for each athlete that is recorded at the beginning of the pre-season. We get three jumps on the first two days, for a total of six jumps. We take the average of these six jumps, calculate the coefficient of variation of the six jumps, and multiply the coefficient of variation by 1.1. Then we subtract that number from the average of the six jumps. The resulting value is what we call the athletes’ caution number (caution number = jump height average less coefficient of variation x 1.1).

Throughout the season, we take daily measures of the athletes’ squat jump heights and compare these to their caution numbers. The athletes jump two times: If both of their jumps are higher than their caution number, then the athlete follows the training plan as scheduled. Their jump results indicate that they are in a good enough state to train hard.

If one of the two jumps is under their caution number, the athlete will jump a third time. If their third jump is higher than their caution number, the athlete will follow the training plan as is, but we will monitor them a little bit more closely. If both jumps are under their caution number, we make the necessary adjustments to their training plan. Generally, we reduce volume, and we possibly reduce load or consider making additional adjustments to other training variables.

A specific example of how we’ve adjusted training based upon the athletes’ jumps occurred at a time when we had most of our players jumping below their caution number. We were scheduled to perform four sets of two on cleans that day, and three sets of three on back squats. We ended up cutting out all of the sets of cleans and just got right into our squatting sets. The following day, our jumps went back up to their normal range.

We have access to Tendo Units as well, so when we have only a couple athletes jump under their range, we can give them a speed range to hit that is a little bit faster than what is planned for the day. This will lead to lightening the load, but the intent should still be there because the athlete is moving the bar as fast as they can. The good thing about having a small team to work with is that we can more readily individualize the training program.

One problem that we sometimes see when having the athletes perform the squat jump is that after they pause in the bottom position, they want to quickly dip a little bit lower and innately turn it into a countermovement jump. When that happens, we just have them perform another trial and remind them not to dip a second time.

Video 2. A squat jump performed with improper form, with a dip that mimics some of the qualities of a countermovement jump.

The Jumps as Metrics: Vertical, Approach, and Squat

A vertical jump is a standing countermovement jump for maximum height with no approach steps, while an approach jump is a jump for maximum height using self-selected approach steps prior to the jump. Typically, volleyball programs test the vertical jump and approach jump to measure improvements pre- and post-macrocycles in training. These two types of jump tests have been shown to be correlated to other athletic performances, such as sprinting ability and change of direction ability.3

The squat jump is a standing jump for maximum height with hands on hips at a self-selected squat depth with no countermovement. The squat jump is a common test for researchers with a force plate that can measure:

- Takeoff velocity

- Rate of force development

- Starting gradient (1/2 peak vertical force divided by time at 1/2 peak vertical force)

- Acceleration gradient (1/2 peak force (time to peak force minus 1/2 time to peak force))

- Jump height

There are many advantages to using the squat jump in a monitoring program over the countermovement jumps. There is less intra-subject variation in performance in a squat jump compared to the countermovement jumps, which allows for a smaller co-variance and, therefore, a smaller window of performance and more reliable measurements. Also, psychologically, volleyball players are not worried about seeing low jump heights on the squat jump because they know that it is supposed to be lower than a countermovement jump. Because they do not jump as high, the exercise itself is less intensive compared to the countermovement jump.

Since jumping is a skill that is part of every volleyball game—and research suggests there is a strong correlation between vertical jump performance and fatigue and athletic performance in other skills—we measure it daily to get feedback and adjust training.

You could argue that using a countermovement jump would be more useful to test volleyball players because it is more specific to the way they jump on a court, it includes the stretch shortening cycle, and it includes a buildup of muscle stimulation, as well as allowing elastic energy to contribute to the performance.2 One study compared the differences between different types of jumps and found that concentric neuromuscular activity does not seem to vary when the subject is attempting to maximally jump, while eccentric neuromuscular activity does vary depending on factors such as landing, speed of movement, etc.4 Utilizing the SJ eliminates all of the other noise that may or may not contribute to jump height performance.

However, having a higher squat jump may have just as much or even more value, as it reflects the capability to reduce the degree of muscle slack and quickly build up stimulation, which is important to high-intensity sports such as volleyball.2 Another point to consider is that it takes approximately .4 seconds to produce maximum force5, and the squat jump reduces the amount of time allotted for the athlete to produce force, possibly indicating the fatigue or freshness of their neuromuscular state of well-being.

A high squat jump reflects a capability to reduce the degree of muscle slack and quickly build up stimulation, which is important to high-intensity sports such as volleyball. Share on XDue to time and the number of players, it is not logistically feasible to track all three jumps for all players on a regular basis, so we just use the squat jump.

Sharing Our Data with the Coaching Staff

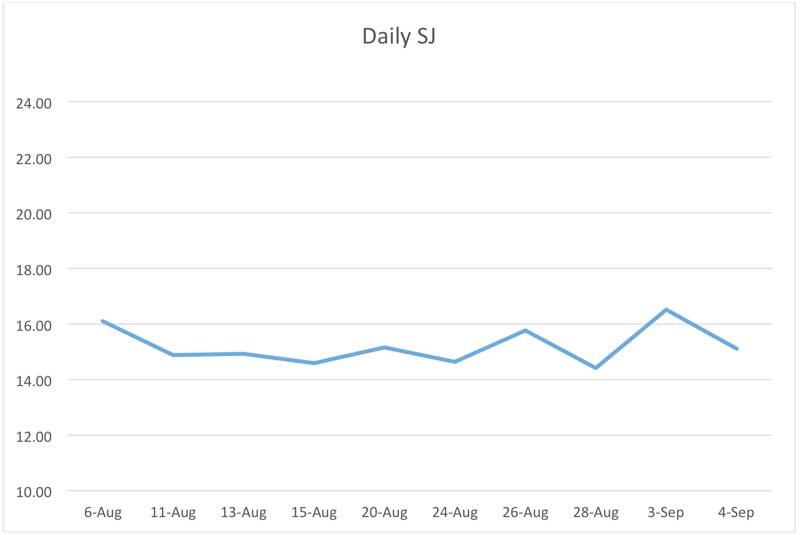

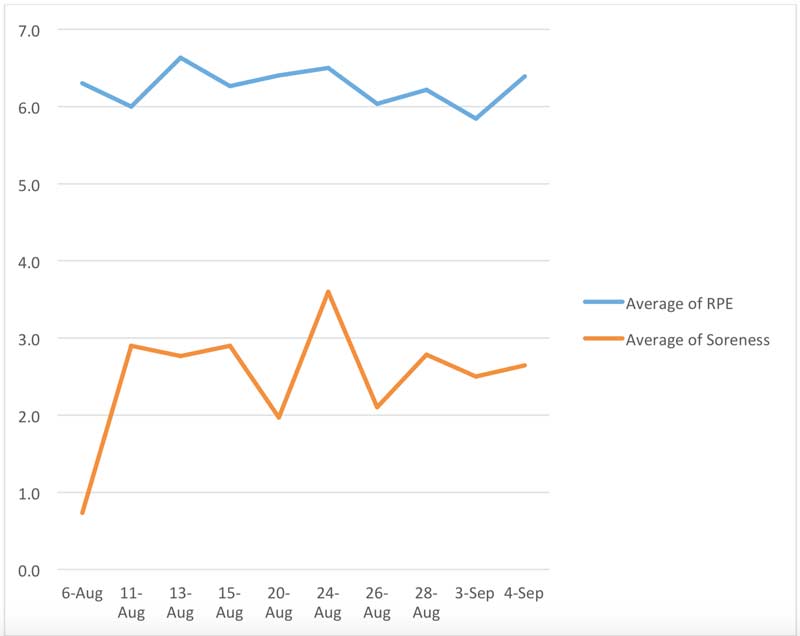

We track all of the athletes’ squat jump trials throughout the season and periodically share our findings with the coaching staff. We provide this in both table and chart formats to easily visualize trends.

The coaching staff appreciates actionable data that they can implement into their practice and game preparation as they consider the athletes’ physical status and fatigue. On top of the SJ tracking, the athletes also fill out a session Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) after every training session we do, along with a soreness grade on a scale of 1–5. Some may not like using RPE, but if you can establish trust with some of the older athletes or the captains on your team, it can be a useful tool.

As an additional factor in our athlete monitoring program, we also track body weight: not necessarily for fatigue management, but as a way to hold the athletes accountable to make sure they get enough food in throughout the day. As I mentioned above, our team practices at 6 a.m.—knowing how college students sleep, it is unlikely that they wake up early enough to make breakfast. Most of them probably roll out of bed at 5:30 and head straight to the gym without eating more than some toast or a protein bar.

Tracking body weight helps reduce some of those habits when the scale shows that they are down 6 pounds from the previous week. It is also interesting to check if there are any correlations between body weights and jump heights on a daily or weekly basis. We haven’t noticed anything as of now, but it can’t hurt to continue collecting data—perhaps I’ll learn more about what to do with the information down the road in a way that can help enhance our program. The system we have now works for us, and hopefully we continue to grow and expand our abilities on this subject to keep improving.

We are fortunate enough to have access to two pieces of reliable technology: Just Jump mats and the VERT monitoring system. The players wear the VERT every day during practice, and it provides live recordings of jump counts, jump heights, landing impacts, etc. Our volleyball staff finds VERT very useful during practice and even during games. If you do not have access to this type of technology, you could always just use a Vertec or a G-Flight by Exsurgo Technologies. It is all up to what resources you have access to and what your situation is.

We previously tried to monitor our athletes’ fatigue using the Tendo Unit. If the athlete doesn’t hit the targeted velocity on their first set, then load gets reduced. There are, however, two problems I see with that method. First, if we only use the bar speed, we only reduce absolute load, when in reality it is probably best to reduce volume instead. Second, our athletes play sports, they are not powerlifters, so their bar speed will have much more variation from rep to rep since they are not necessarily elite barbell athletes.

So, it is a tool—and a useful tool—but we are finding more success using the squat jump at the beginning of our sessions right now. The goal from here on out is to continue building on what we are doing: making ourselves better to improve the performance and the lives of the athletes that we train.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Gambetta, V. (1999). “Plyometrics: Myths and Misconceptions” [Web log post]. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

2. Van Hooren, B. and Zolotarjova, J. “The Difference Between Countermovement and Squat Jump Performances.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2017; 31(7): 2011–2020.

3. Köklü, Y., Alemdaroğlu, U., Özkan, A., Koz, M., and Ersöz, G. “The relationship between sprint ability, agility and vertical jump performance in young soccer players.” Science & Sports. 2015; 30(1): e1–e5.

4. Jarvis, M. M., Graham-Smith, P., and Comfort, P. “A Methodological Approach to Quantifying Plyometric Intensity.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2016; 30(9): 2522–2532.

5. Zatsiorsky, V. M. and Kraemer, W. J. Science and Practice of Strength Training. 2006. Champaign, IL.: Human Kinetics.

Hey Will, could you tell my why you multiply the coefficient of variation by 1.1 ?

Regards Luca

Great article, thanks.

Can I ask if the caution number a rolling number? Ie does it take in consideration for improvements in leg strength and specific skill adaptations to jumping daily, especially for a new athlete. If not it could be that fatigue is being masked and toy get a false positive.

Also how do you adjust for beginner effect?