The term “individualized” is used so often that it’s a common, accepted fact that coaches are individualizing workouts. Or maybe no one has cared enough to reply to those professing to individualize workouts, “Cool! Can you show me some examples of two players at the same position with two training programs that are very different?” as this may have proven a practitioner was not exactly honest.

My educated guess would be that there are probably several definitions of individualization floating around. I don’t think coaches are flat-out lying or being pretentious. They really think that they tailor their respective programs specifically for each individual. But what exactly does it mean to individualize a program, knowing that there are certain physical aspects that cannot be ignored in a training program for entire teams, but also that each athlete’s body needs different things? How much individualization is needed, if any, and how much is too much?

What I Have Learned the Hard Way from 30 Years in the Trenches

Each sport has inherent physical qualities, movement patterns, and energy sources that all athletes must be held accountable for if they’re to have any personal or collective success. I understand then that there are some similarities in training programs amongst a team. I’ve always said that if I showed you a lifting program, you should not be able to tell me exactly what sport it was designed for. Maybe you could rattle off a few possible sports it could be for, but nothing apparent should say that it was 100% this sport or that sport.

The rotational sports—tennis, golf, baseball, softball—are a good guess when you see rotational exercises, but then so are discus, shot, javelin, and hammer. Even with the heavier poundage, you couldn’t pick one out of the four throwing sports with total certainty. A shoulder program could easily be for tennis, water polo, volleyball, baseball, softball, or swimming. It would be the leg programs that throw you off the scent, with all of them likely squatting and pulling. Even the conditioning and movement programs should be along the same lines—lots of crossover energy sources and drills over an array of sports. But this is really talking about a word I hate to use—“sport-specific”—and less about athlete-specific for the sport they play.

I can illustrate this stance with my recent work with Division I male basketball players. In short, returning players’ programs were individualized enough that they could not partner up with each other. At times, a few players started the session with the same platform exercises, but even then, the percentages for that day were different. The order of the exercises was different, the menu was different, some athletes performed a light day while others were 90+%, and so on.

For the most part, freshmen and incoming players had identical programs. True freshmen were really the same kid—I’ll explain this later—and had pretty much the same core menu for the entire first year. Incoming players start out that way because they come in older and with a little training background, but progress much faster than true frosh.

Still, I want to see what they have done and what they can do, so they begin with the freshmen. It’s not lost on me that when you have 15 athletes with individual training times (usually in groups of three to four) and three or four other coaches helping, it is much easier to implement personalized programs. Yet, I still say if a group stays around 20 athletes (even a 1:20 coach/athlete ratio), each one of those athletes should have tailored programs, aside from the frosh and incoming.

Of course, logistically it doesn’t make sense to not pair up the team and it creates an administrative liability when you have fewer platforms than athletes. Nonetheless, a good level of custom-made programming should exist. So, even though the program design for a team must have a root menu for the sport, the real roots need to be established in physical goals and the path each athlete needs to take to get there.

The Cornerstone to Tailoring Training to Athletes

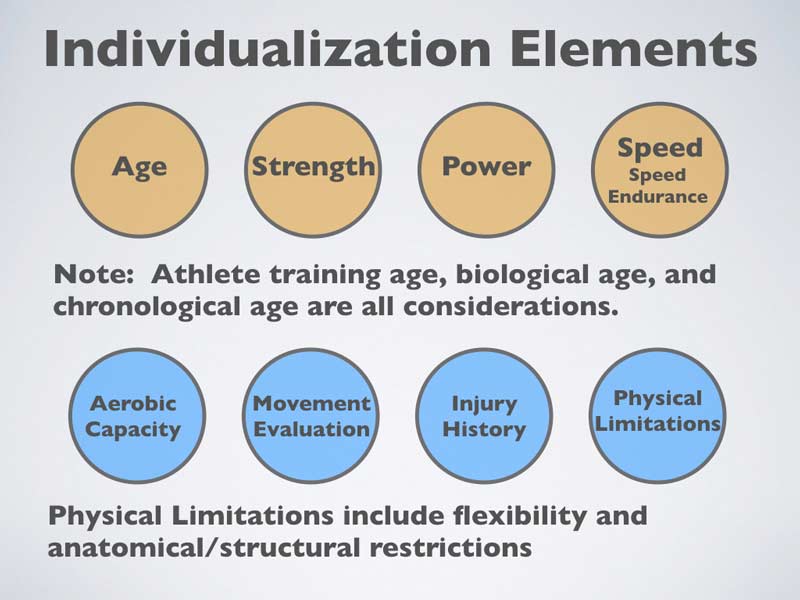

The foundation for this article is that individualized training, by definition, should mean a program design based on the physical assessments of each athlete, outside of the somewhat distinctive exercises of a given sport (not to exclude nutritional and psychological influences, which are outside the scope of this paper).

Let me also set some ground rules going forward. These actions are NOT individualization:

- Using percentages of RMs for team prescription. Let us all assume that no one would tell a team, “We are all squatting 300lbs for five sets of five today.” Of course, you would have each athlete handle weight that is individually appropriate.

- Adjusting workouts based on injury. My intuition tells me that coaches would not have an athlete do a barbell bench press when they have a broken wrist. Adjusting workouts due to injury is just what you do…every time!

- Implementing med ball twists for rotational sports. Exercises that are programmed based on the sport do not count.

- Using the same workout card but changing the athlete’s name. Do I really have to explain this one?!

Decision-Making and Criteria for Customizing Workouts

When designing tailored programs, you should consider the following arguments and relevant questions:

There’s no need to individualize all the time.

Sometimes you just can’t individualize. I can’t remember when, where, and who, but I remember a discussion about “being up with the times”—a.k.a., being current. The coach said to me, “Every year you and I get older, but the freshman kid is the same age every year.”

This observation held a few meanings for me. First, that you can’t stay so set in your ways that you don’t roll with the fads or see the signs of the times. If you do, then what you do is irrelevant because it just doesn’t work that way anymore.

Secondly, from a training perspective it holds true for me to this day: Freshmen have essentially been the same kids that I saw at UCLA in 1984—untrained, with a chronological training age (CTA) at beginner level. (CTA is an objective assessment of time spent training, and the level and result of that training since the athlete has been under supervised, organized training. It is independent of the athlete’s birth age). They are athletes waiting for the highest percentage increases in physical capacities and qualities than at any other time in their lives.

I’m a firm believer that collegiate freshmen do not need individualized programs. And don’t assume incoming athletes (transfers) have trained the way you want them to or have adequate strength levels because they are older. Incoming athletes (transfers) should start on the frosh program and an assessment should be made as to how long they will remain on the frosh program. Technique is the first test they must pass to progress to poundage.

When we talk about early specialization with younger athletes (I consider high school athletes in this group), we must include weight training as part of the conversation. It’s never brought up and it should be. From a scientific standpoint, we cannot dismiss that this group is as untrained as they come, meaning that 100% of all early gains in strength will be solely from neural factors. Plus, that neural time frame might last a year, or maybe two! Wobbly bench presses and squats will tell you that much.

While the athlete is in this phase, there is absolutely no reason to make the training more complex, based on one training axiom, “Always perform the least amount of work with the most gains.” I’d even suggest that after six to eight months, if the athlete is still securing good technique and making good gains, adding more complexity to the training will most likely lead to decreases or at least a slowing down of progress, not greater gains. I will call it neural overload.

I confess that I don’t have any data to prove this, but think of it this way: Just because I am improving—not mastering—juggling three baseballs, it doesn’t mean that if you toss me a fourth ball (a more complex skill), my rate of improvement gets better! Still, after acquiring technical proficiency and strength, and therefore speed, power, etc., and at some point, muscular effects, the athlete will continue with a consistent rate of progress up to their senior year.

I think we can all agree that a senior in high school will not be “tapped out” in terms of physical prowess gained from resistance training. Sure, there will be some modifications, but in no way would I call those modifications “individualizing.” I contend that high school athletes can make the same amount of progress with very little, if any, individualizing that they would with some of the circulating complex training programs we’ve all seen, in the same four years. High school programming could be an entire article by itself.

Resources also govern whether personalized programs are appropriate and, if so, to what degree. The number of athletes in the room, number of strength and conditioning coaches available, knowledge base and skills of the strength and conditioning coaches, equipment available, time allotment—these are all general issues of programming and definitely impact how detailed a coach can get.

While the time allotted for training affects a program menu every time, the amount of time it takes to design a program isn’t looked at. If you are doing it comprehensively, then you are using the assessments previously mentioned. If there are only two to three full-time strength and conditioning practitioners and 400+ athletes coming through the doors (many NCAA institutions are like this), then performing the assessments, analyzing the assessments, and implementing (programming) the interventions that go with them is a laborious job that is time better spent elsewhere…like sleep!

Assessments are important. Without them, you are on an adventure with no destination. Or, like I say, you’re just guessing when you write programs, and hope is a bad strategy. While there might not be a thorough personalized approach in a team setting for several reasons, it is necessary to put special programming in place where it is practical and effective.

Don’t individualize by birth age or skill level.

I touched a little on CTA above, and the importance of depending on that age as the mark by which you organize the training. It should have the most influence on program design. Still, the collegiate setting sees many athletes who come in as freshmen (17-18 years of age) and have not participated in an organized strength and conditioning program or long enough (not enough time or strength) to be past the beginner range.

Chronological training age (CTA) should have the most influence on program design. Share on XLikewise, transfer athletes may have some training background, but may not be physically or technically prepared for the new school’s program. Fernando Montes, former longtime MLB strength and conditioning coach, gave me great words to live by when he was preparing training program design for newly drafted pitchers of any age. He said, “Treat them as damaged goods.” For the most part, he was referencing their throwing arms, and it made the training conservative and, at the same time, safe and effective.

Basically, assume nothing! In summary, no matter how old an athlete is or looks, and no matter how long they say they have been training, start them at the lowest level. You can always ramp it up. I’ve seen it too many times—an athlete says they bench press X amount of weight or “I know how to power clean” and, when they attempt it, the actual amount of weight they can bench isn’t even close or you’d have to widen the definition of the power clean so you could actually call it a power clean! When athletes tell me they “know how to do it,” I tell them, “I’ll be able to see that, and when I do, we’ll move forward” and go from there. No further discussion.

Individualizing programs by skill level will, without a doubt, inhibit physical growth potential. Period. Looking at a few sports where younger athletes will soon be in the professional landscape, it could be easy to adopt the programs of athletes at the same skill level who are significantly older. The NBA and MLB are two such places where just-graduated high school seniors and collegiate underclassmen—freshmen in the NBA—play almost immediately upon their arrival to their new team.

Individualizing programs by skill level will, without a doubt, inhibit physical growth potential. Share on XYou could ask, if they are at the national or elite level, how much growth potential remains. It’s a fair question, but in this case, I am talking specifically about younger athletes. Physical growth potential remains high because of the low CTA. For that reason, there could be a beneficial effect on performance when the athlete gets stronger, runs faster, etc.; an improvement not likely made by older athletes. Plus, there is a significant physical stress difference between the next level and the level these kids were just at. So, at the very least, administering developmental-type training becomes a surefire way to immediately manage injury from a neural and physical capacity overload.

Individualizing based on absolute strength vs. relative strength.

Going back to the original premise that athletes with a younger CTA need not be individualized, strength values are somewhat meaningless in the beginning for them. Not every just-starting-out athlete comes in with their strength levels at zero. For instance, I knew Natalie Williams as an exceptional collegiate freshman. She played volleyball and basketball at UCLA, and was the first woman to earn All-American honors in both in the same year. Natalie was a two-time volleyball national champion and Women’s Basketball Hall of Famer; she was also a terrific, upbeat person. As a freshman, her first legitimate squat test was a wobbly 140kg (308lbs). This is where the common sense comes in.

You might see this in every article I write:

Common Sense + Intuition + Science = Best Results

Because she was the best player in the country at both the sports mentioned, the risk-to-benefit ratio of continuing to push the limits of her squat was, in my judgment, not a good idea. She would have squatted 400lbs in one year’s time, which is only a 29.8% increase. I’m sure of that—again, she hit a wobbly 140kgs!

We continued to squat moderately heavy (75-90%), but I did not test her back squat again. Instead, when I felt the load looked easy for a given projected 1RM, I changed the load and re-estimated. However, as I say, I did not raise the new 1RM with any vigor on my part. To be clear, just because I didn’t test the back squat doesn’t mean she did not improve. I looked for other metrics to let me know her leg strength was fine. You can apply this idea to literally any exercise.

I still pushed development and tested in the other areas—pulls from the ground, basic incline and flat bench pressing, basic plyometrics and jump testing—which satisfied her physiological needs. This also points to an important aspect of training: Just because you train a lift doesn’t necessarily mean you must test it. I relied on the comprehensive nature of the programming to get to our goals of health and power; not just one lift.

The moral to the story is that strength levels don’t determine programming with beginning athletes. There might be some exceptions to parts of the programming and goal-setting for those close to or consistent with advanced strength levels in lifts that have inherent risks associated with them. However, the remainder and majority of the program should still be developmental.

There are times that older athletes don’t progress at the rate expected over a one- or two-year period in one or more qualities. We’ve seen this, right? The combinations of good news/bad news are endless: vertical jump increases with little squat progress; squat increases with little power clean progress; squat and clean increases with little progress in short sprint times. Naturally, individualization of those areas that need attention must happen. Nevertheless, it might not only be strength. It could be a lack of power, flexibility, mobility, or technique that holds the athlete back from progressing.

For example, if it’s technique slowing down development, then take caution with the load and volume schemes of the other parts of the program. Sensitivity to volume must be at its peak because, as we all know, it is very difficult to hone technique when there is a background of fatigue. Sprint technique will suffer if the legs are tired, but upper body fatigue has a deleterious effect as well. Pulling from the ground, if not well-monitored, could drain back strength and affect squatting patterns. Conversely, demanding squat workouts will make pulling from the ground a chore if the squat training is not modified while working on pulling skills.

Strength levels don’t determine programming with beginning athletes. Share on XIf “the plan” goes better than expected (Hallelujah!), then it is categorically time to get personal. Keep in mind that it’s not rare, but it shouldn’t happen often. And, I’m not talking about in the first 8-12 months; there is still much to be gained. It’s more like in 14-24 months.

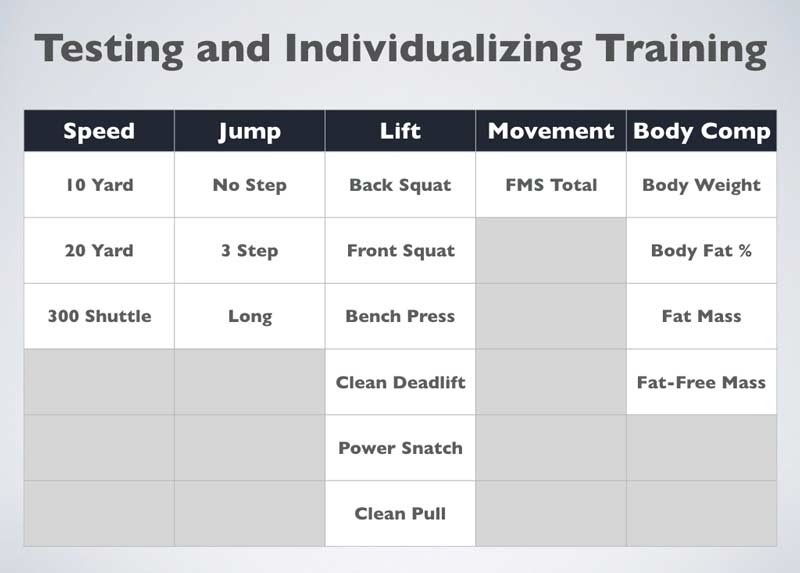

Ironically, while we talk about designing programs specifically for each athlete, for the most part we deliver a program that has essentially the same goal for everyone in regard to teams or groups: 400m sprinters, point guards, shortstops, 100m freestylers, wide receivers. It’s just that some of the methods might be—should be—different for each athlete. This is the reason there should be a comprehensive athlete profile kept for each athlete, chronicling all the assessments and testing over the duration of their career or at least their time in a setting.

This will give the practitioner an idea of how much progress to anticipate in each of the testing/assessment categories based on homogenous group standard deviations, averages, and comparisons over any segment of time (year to year, year 1 to year 3, year 2 to year 4, etc.). Based on the data, an athlete who reached enough strength in the squat can progress to a program based less on strength and more on speed, and the profile can also indicate a longer stay in a training block for an athlete who lags in some areas. Collaterally, this data will inform the sport coach of the physical profile of the athlete they are recruiting and their expected growth patterns.

Individualizing based on movement pattern quality.

Technically, we must do this. If squat patterns, running technique, or shoulder mobility aren’t great, then, as the saying goes, it’s not a good idea to put strength on top of dysfunction. What should you do if that athlete is a full-time starter; one of the better players on a team? I’m a firm believer in the FMS and, at the same time, know that you can’t just keep doing light corrective exercises. At some point, you gotta get ’em strong!

With younger athletes (up to 21-22 years old, I’d say—collegiate seniors), it’s not as if they are a dumpster fire waiting to happen if the screening score is low. Although it may mean that poor movement corrected will produce a more efficient power/strength/speed delivery system. I believe that if you don’t compromise poor movement with half-assed technique to accommodate heavier loads, you can work on strength and correcting patterns with younger athletes. Keep in mind though, until those patterns clear up, it makes no sense at all to test strength levels in the given exercise. In other words, if the goal is to get the hamstrings parallel to the ground for an appropriate squat depth, testing at a depth higher than that serves no purpose.

Progress while correcting movement is not the improved strength of an incorrect pattern, but rather an improved pattern towards the correct pattern. The lifting part is easy; you can separate those that need help from the rest of the team during a training session. But what about conditioning sessions? Now those are a different beast. Candidly, you might just have to play it out with the young or beginning player. Personally, I have not seen someone with a poor screen score or poor movement pattern break down during conditioning.

I’m sure we’ve all seen the frosh group come to the collegiate setting thinking they are in shape until the first conditioning day, then…whoa! We can’t really blame that on poor movement quality. Of course, if movement quality problems do occur, then adjusting (what we do best) happens instantly. You need to implement other modes of exercise to effectively condition the player. Just as importantly, convey the reasoning to the sport coach so they know the mechanisms in place, and what the future could look like for this player if they ask him to “gut it out.”

Older athletes and professional-level athletes are quite a different story. We’ve all heard and seen, especially working at the professional level, that successful athletes and veteran athletes are great compensators. This group must have personalized training for no other reason than their livelihood and health depends on it! Add in the fact that their bodies have morphed around whatever it has taken to be successful—good patterns, strength, speed, and flexibility be damned!

That said, an education must be delivered to all involved—coach, GM, player, ATC, and physician. At some point, compensation is not going to hold up (to say nothing of the aging process) and keep injury or physical limitations away. The program design needs caution and development at the same time, and let me tell you why.

As I write this, I realize that this might be the one exception to my view that older professional athletes need not focus on development. Joe Kessler, strength and conditioning coach of the Cleveland Indians, has been a huge influence on my functional movement screen knowledge and application. We were discussing improving movement patterns when he made a statement that I hadn’t thought of.

These guys were successful, albeit with certain patterns that could use improvement. What happens if a player gains greater range of motion in his swing or stride? Could it change how successful they are? Or worse, could they injure themselves because of the new ROM without accompanying strength and power increases that are difficult to get within one season?

It made me pause, and at that moment I added it to my philosophy: Take great caution in improving certain movement patterns in older athletes because there is a risk that is tough to measure. Not that you wouldn’t try to clean up asymmetries or dysfunction, but a carefully constructed program must consider many other physical qualities that dovetail in a timely fashion so it doesn’t disrupt elite skill sets or create a fertile ground for injury.

Without a doubt, individualize by position.

Let’s be clear though—the individualization does not stop there. Offensive lineman in football are a great example. Position breaks down into a few sub-positions, as seen on this chart.

Some Last Words on Individualization

When it comes to individualization, some coaches have said to me by way of excuse, “You know, our sport is unique. It’s different than the others.” Yes, coach, your sport is unique. That’s why each sport has its own name. And no, it’s not different to the strength and conditioning community, in that every sport has movement patterns and energy sources—that’s what we look at. Are there any sports that we should or should not individualize? No.

Another question goes something like this: “Do we individualize for one athlete that goes to bed at 10:00 p.m. and one who goes to bed at 2:00 a.m. on the same team for the 9:00 a.m. workout?” If you say you individualize, yet know that a kid is not getting sleep, has serious family or relationship troubles, or hasn’t eaten anything all day, and you don’t make immediate training changes, then I’m calling BS!

Personalizing programs daily is the ultimate move by a strength and conditioning coach. Share on XThis is where personalizing the programs daily is the ultimate move by a strength and conditioning coach. A weight is too heavy so you lighten it up, a lift is too complex so you simplify it, a conditioning drill begins to look like a health risk to an athlete so you pull them out—this is not customizing a workout. It’s like breathing; you should be doing it every day.

When a coach begins to look outside to variables that affect the training, and makes adjustments because of them, that’s when you have something special as a philosophy. Some coaches say they individualize programs, but for that to be accurate you’d have to significantly widen the definition of “individualize.” I’d say it doesn’t happen as often as folks say it does. Though, to be fair, you can’t really customize programs all the time and often not to the extent that you could or would like to.

I will concede that, like “The Basics,” there is no solid definition of individualization, but we still should be able to discern what it is. Much like telling the difference between jogging and running, it’s hard to explain, but we know what it is when we see it. The goal, the quest, is to tailor as much as possible for each athlete while not compromising the physical goals necessary for sporting accomplishment.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

It’s nice that you mentioned that you can’t expect everyone to perform the same. I liked your example of squatting three hundred pounds and how ridiculous that made it seem because it illustrated the point extremely effectively. I think it’s also important that athletes themselves don’t expect to train the same as others and that training is a very individual thing.