In July 2019, Baxter Holmes wrote “These kids are ticking time bombs—the threat of youth basketball” for ESPN.com, an in-depth article on the dangers of high volumes and over-specialization too early in an athlete’s maturation. Despite being written about basketball, the epidemic Holmes identifies is a general narrative amongst all youth sports, with soccer, softball, baseball, and volleyball all demonstrating similar paths to early specificity.

As the strength and conditioning coach for the Pittsburgh Riverhounds Development Academy, I have also witnessed the growing trend among our young athletes to identify strictly with one sport at increasingly younger ages. This same perpetual cycle appears to be the norm regardless of sport: extra, position-specific skill lessons scattered around team trainings throughout the week, culminating in weekend competitions. Well-intentioned, but slightly misguided, these youth sports operate under the misconception that more is always better.

As a result, young athletes (and their parents) have entered an open arms race to acquire as much technical skill work and attend as many “elite” showcases as possible. There is, however, an important distinction between development and demonstration. Continually prioritizing games, tournaments, and showcases at the expense of holistic development too early in an athlete’s growth will likely be unsustainable—not just as a detriment from a health and wellness perspective, but also a potential limiting factor as it relates to higher levels of skill acquisition. A lack of exposure to diverse motor patterns early can stunt growth late. As complexity continues to grow for increased sporting mastery, a lack of foundational motor function can inhibit further technical progress.

What athletes once organically acquired by playing different sports over different seasons now has to be achieved through well-thought-out, systematic performance training, says @houndsspeed. Share on XWhat athletes once organically acquired by playing different sports over different seasons now has to be achieved through well-thought-out, systematic performance training. As a result, I have comprised a hit list of both general and special preparedness exercises that not only build resilience, but also provide an enriched motor environment to sustain healthy, long-term growth in the one-sport youth specialist.

Specificity of Preparedness

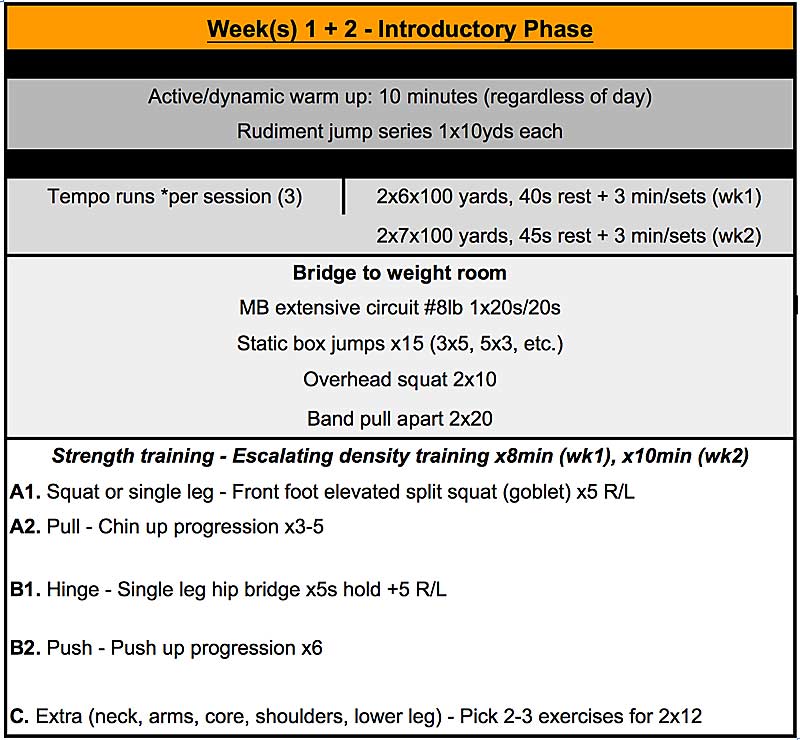

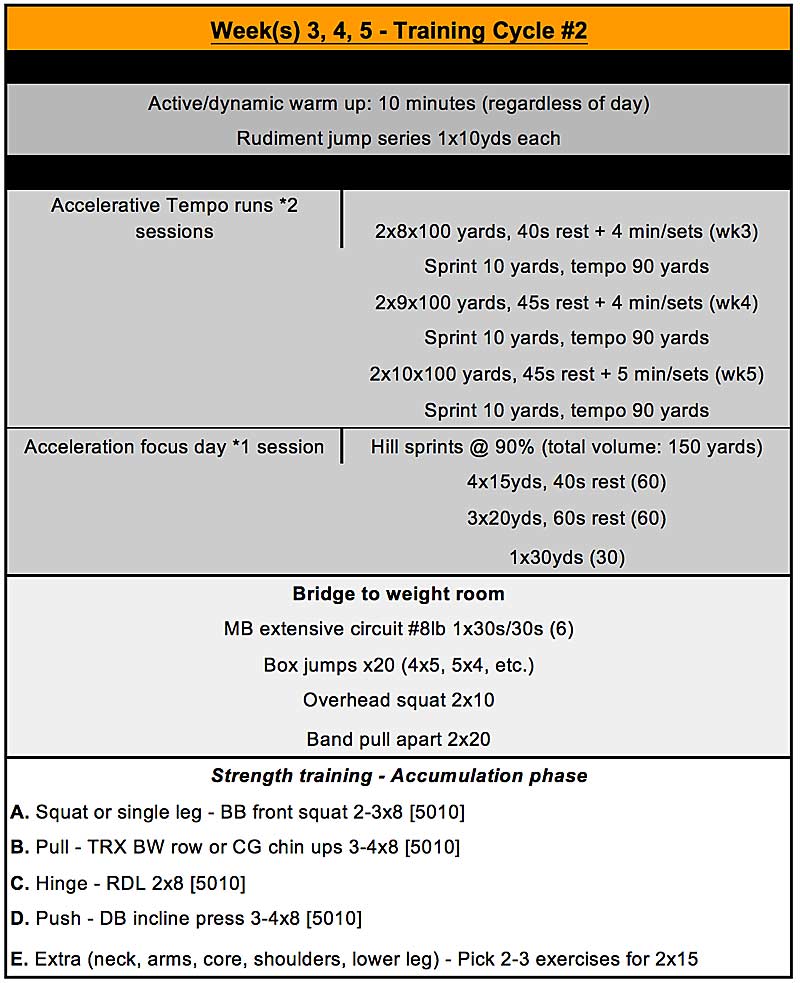

Preparation training should be effective, efficient, and nondisruptive to the two tasks being prepared for: training both to enhance performance in the specific sport and to fill motor gaps left by early specificity. Throughout the pursuit of fulfilling these two goals, performance coaches need to remain mindful of the fact that we are not trying to replace one sport for another, nor are any trophies won for excessively fatiguing athletes or inducing unnecessary soreness. There is tremendous value in being succinct, and like most things in life, the simplest answer is often the best.

The off-field physical preparation process should start by developing broad athletic principles and gradually narrow as progress is made toward more desirable traits. The difference between general preparedness (GPP) and more specific preparation (SPP) can be subtle. From a broader perspective, general preparedness exercises teach global concepts under minimal stress.

Maintaining a comparatively low magnitude and preparing for what is to come is of greatest consequence. Special preparatory exercises come closer to the velocities and stresses experienced during play, and the direction of the application of force also takes on greater significance. Some examples include:

- General prep: Basic strength work and in-place jumps.

- Special prep: More elastic and develops sustained, rhythmic horizontal displacement in all planes of motion.

- SPP: Skipping, bounding, lateral shuffling, and sprinting.

Good physical preparation should also include an appropriate blend of tension and torque-oriented exercises with special consideration given to the force-velocity relationship reflected by the sport itself. Increased time under tension is most associated with developing strength, and building strength is necessary regardless of the sport to enhance an athlete’s ability to produce force and increase their resilience to injury.

Video 1. Split jumps exemplify the subtle differences in GPP and SPP exercises, as these in-place jumps include a sustained, rhythmic element.

Rate-of-force themed exercises train an athlete to quickly demonstrate their strength. For nearly all ball-court athletes, most of their preparedness should reflect this. To play explosive and fast on the competitive field, you must facilitate those same attributes in the training hall by moving as dynamically as possible with zero external resistance and lifting light-to-moderate loads as explosively as possible (Verkhoshansky & Siff, 264.) Repetitive efforts and maximum efforts also must be done, but not as frequently. This general ethos is the foundation on which the Houndsspeed philosophy is built.

Radcliffe-Inspired Unilateral Jump Progression

High-Powered Plyometrics by Jim Radcliffe and Robert Farantinos was first recommended to me by Carl Valle, and it did not disappoint. Like the more widely known Supertraining by Verkhoshansky and Siff, High Powered Plyometrics delivers a highly scientific approach to speed and power development but in a much simpler, reader-friendly way. Loaded with logical and highly effective progressions specific to nearly every sport, this book is on a short list of must reads.

In particular, the single leg jump progression presented by Radcliffe and Farantinos satisfied both my desire for simplicity and the need to develop multiple traits concurrently, such as:

- Power.

- Speed.

- Proprioception.

- The ability to rapidly decelerate.

Video 2. Single-leg tuck jumps are part of a unilateral plyometric progression inspired by Coach Jim Radcliffe.

The best exercises are able to build the greatest number of attributes by the simplest means, especially when physically preparing an athlete who is already dedicating significant time and energy to the technical and tactical aspects of their sport. The one-leg jump progression certainly checks many boxes. Beginning with in-place single response efforts in which the landing is valued just as much as the takeoff, this is progressed by imposing greater speed and motor complexity before building out to more elastic single leg leaps in which the center of mass is displaced.

The best exercises are able to build the greatest number of attributes by the simplest means…and the one-leg jump progression certainly checks many boxes, says @houndsspeed. Share on XI appreciate this progression because of the smooth intensification from general characteristics to more specific desirables with a steady rise in both stress and skill, while simultaneously promoting strong pelvic position. Strong pelvic control is essential and an underlying theme that is a requisite for efficient movement. The single-leg jump progression is also fantastic at recruiting the opposite glute and hip simultaneously, which has strong carryover to good sprint mechanics. The progression is simple, but not to be confused with easy. It looks something like this:

- Single-leg pogos

- Split jumps

- Scissor jumps

- Double scissor jumps

- Single-leg tuck jump (in place)

- Single-leg leap (distance)

- Lateral single leg hop

As with any power- or speed-dominant exercise, low volume and high intensity is best. Approximately 4-8 total jumps per set and 2-3 total sets per exercise is optimal.

Videos 3 and 4. Progressing from the scissor jump to the double scissor jump.

Horizontal Skips, Jumps, Bounds

While the vertical jump might receive the most attention when it comes to assessing power, it only tells a comparatively small part of the story as it relates to soccer athletes specifically. Being able to rapidly generate force to overcome both inertia and gravity will always have value, but the vertical jump is a singular moment that illustrates brutish strength more than fluid, rhythmic athleticism.

For this reason, I value continuous horizontal jumps and bounds as better indicators of athleticism more than one singular vertical jump, because these movements demonstrate how well an athlete can create and sustain horizontal momentum. Even for more vertical-oriented sports like volleyball and basketball, horizontal jumps, skips, and bounds still have great value for motor development.

Even for more vertical-oriented sports like volleyball and basketball, horizontal jumps, skips, and bounds still have great value for motor development, says @houndsspeed. Share on XAlthough debatable, speed is perhaps the most coveted physical attribute among all ball-court sports, so preparatory exercises that develop and ultimately demonstrate horizontal displacement are better barometers of athletic success. Specifically, the triple broad jump and six-step alternating bound have much greater carryover to short accelerations, and academy athletes use objective measures like those the Probotics Just Jump Mat, Freelap Timing System, and a simple tape measure provide as evidence to support a heightened sense of value to horizontal efforts.

Through the years, I have found one of the most effective and time-efficient ways to develop horizontal displacement is to take the more extensive, less stressful skill development exercises such as marching, skipping, prancing, and galloping and impose specific ground contact limitations while simultaneously asking the athletes to just simply cover more ground. Imposing limitations on ground contacts serves two purposes:

- Drives intent and forces the athlete to consider every ground contact.

- Allows the coach to monitor volume.

This requires no quantitative measurements (although the movements can be measured), and embedding these within warm-ups for nearly every session adds up fast and exposes the young athlete to the feeling of “getting out” with a variety of cadences and movement strategies, providing the necessary diversity to be drawn upon later.

Stairs, hills, and resisted variations of the same exercises are also fantastic at teaching horizontal displacement—these mitigate the stress on the athlete as well by limiting the velocities achieved (and resultant forces). To that end, these variations are great precursors to flat surfaces, not the other way around. This is precisely why physics matter and why it is important to not confuse perceived exertion with actual effect.

Lateral Bounds

Complete preparation for all athletes should also include a sound approach to incorporating multiplanar movements. This is more necessary now than in previous generations because of the lack of movement diversity as result of the increased early specificity. Intricacies in carryover from sport to sport—like footwork in soccer translating to a more efficient lateral shuffle while playing defense in basketball or a wide receiver’s ability to better “high-point” a football because of rebounding in basketball—are now missing. Besides larger concerns—such as appropriate energy system development—coaches must also focus on smaller, more specific details such as direction of force and the planes of motion that reflect the needs of the sport being prepared for.

Lateral movements are potent developers of the glutes, hips, and adductors, so they are of great value to all athletes, but even more so for the multidirectional athlete. This is where I feel more traditional standards in strength and conditioning can lead a coach or athlete astray by perhaps overvaluing linear (sagittal) and vertical forces at the expense of lateral (frontal), rotational (transverse), and horizontal forces. For me, management and the slow intensification of stresses in the frontal plane begin with general strengthening exercises like lateral squat and lunge variations and is slow cooked to lateral marches, skips, hops, jumps, and ultimately bounds.

Admittedly, in the not-too-distant past, I feel I likely spent too much time developing the lower-stress lateral squat and lunge variations when my athletes would have been better served skipping, hopping, and jumping laterally. Lateral movements in conjunction with unilateral strength and rate of force development are the foundation for how I now prepare our athletes for multiplanar agility.

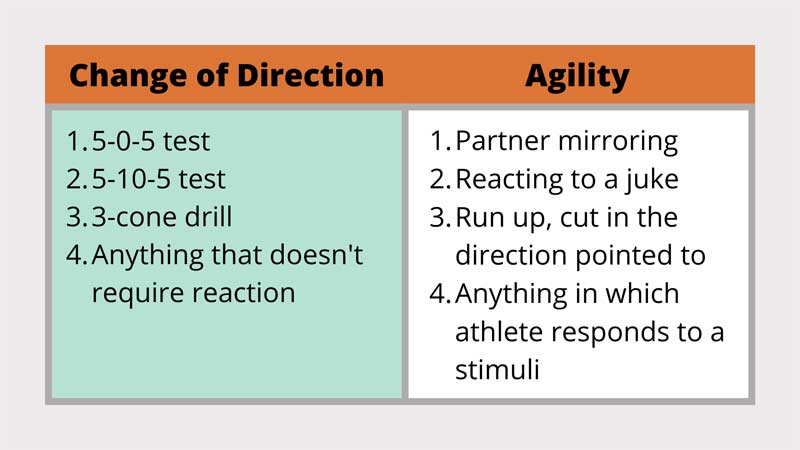

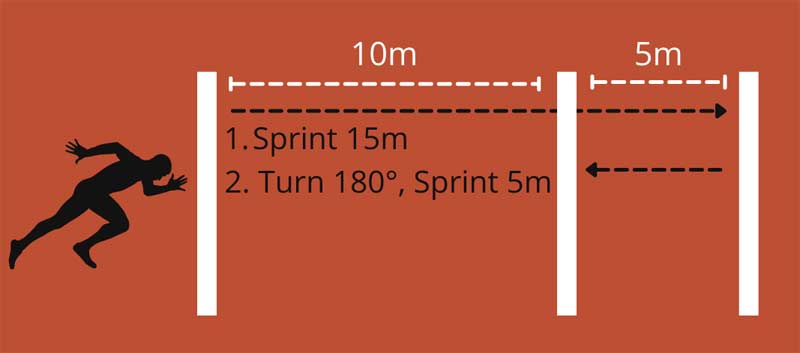

Lateral movements in conjunction with unilateral strength and rate of force development are the foundation for how I now prepare our athletes for multiplanar agility, says @houndsspeed. Share on XWith nearly unlimited degrees of freedom within the game itself, I am not the biggest fan of choreographed change of direction exercises. These exercises are great to develop broader concepts in the youngest athletes, but beyond the earliest stages of development, drills with predetermined paths lack realism. As result, I prefer to prepare our athletes for the forces and stresses they will encounter within the game and let their technical training and intuition develop the specificity necessary.

Video 5. Like the linear skips, jumps, and bounds mentioned earlier, lateral bounds teach an athlete to displace their center of mass, but in an entirely different plane of motion.

With that said, lateral bounding and its variations win the day as they relate to imposing stress in the frontal plane. Developing lateral bounds begins with single response efforts in which landing with a soft knee is emphasized and then progressed to fluid back and forth lateral displacements where force needs to be absorbed and quickly recreated in the opposite direction.

This exercise is harder to quantify because of the rhythmic back and forth nature, so simple qualitative assessments do just as well. Flat discs, tape, and lines on a field can provide good visuals for the athlete and coach alike as to how much separation they are creating with each bound.

As with all my plyometrics—regardless of intensity—I encourage our athletes to rely on feeling the ground as opposed to having to see the ground. Over time, this builds a tremendous sense of kinesthetic awareness. I feel very strongly this not only enhances performance but is also important in preventing injury. As an athlete becomes stronger, lateral bounding can be progressed to Polish boxes and asymmetrical surfaces to create subtle variances in both movement pattern and force.

Med Ball Mayhem

Bending, twisting, whipping, throwing, and catching are all base level motor skills every athlete should possess, regardless of sport. Medicine balls are a great tool for both developing and demonstrating mastery of all these athletic attributes; they can also be used extensively to develop low-stress strength and rate of force while having the potential to be “dialed up” to intense ballistic efforts.

Progress in these traits can be easily objectified with increasing med ball loads and distances on a measuring tape. Even though our field-playing soccer athletes (non-goalies) do not have to throw and catch, these two specific skills are great at developing upper body coordination. Over my tenure with the Riverhounds, it has become painfully apparent that as gifted as some of our young soccer players are with a ball at their feet, they are equally as deficient if instructed to catch that same ball with their hands.

Admittedly, this initially flew under my radar, as I was quick to dismiss it as unimportant. Time and experience have proven otherwise, and I share this in the hope that I can help others avoid the same mistake I made. Lack of upper body motor control is a large void that will negatively impact:

- Speed.

- Efficiency at submaximal speeds.

- The acquisition of more advanced technical capabilities.

Quite simply, max speed, the resultant speed reserve, and advanced technical prowess are full body efforts—therefore, a lack of upper body strength and coordination will eventually become a limiting factor. To combat this, simple partner drills that initially only require handoff exchanges such as med ball over/unders, half twists, and full twists eventually can be progressed to light tosses accentuating the same motor skills. I do not want my athletes catching max effort intensive throws, so I reserve those for expressions of starting strength and rate of force only.

Max speed, the resultant speed reserve, and advanced technical prowess are full body efforts—therefore, a lack of upper body strength and coordination will eventually become a limiting factor. Share on XI do, however, like to measure distances and loads on all intensive throws because I am a firm believer in that which gets measured gets improved. Throws of all varieties—like underhand forward, underhand backward, chest, rotational, and overhead—are great ways to monitor power development in an environment that more closely resembles a field-based athlete’s natural habitat. It is also important to consider utilizing throwing and catching as a tool to develop skill in tracking flighted balls. This is essential for field players timing headers, goalies managing crosses, and the entire synchronization of set pieces.

Again, I missed on this in my younger coaching days—what I mistakenly thought was innate was likely something that must be developed. Growing up playing basketball and baseball, reading and quickly assessing the trajectory of a ball off a rim or a bat was an acquired skill that undoubtedly assisted in my timing of headers. For those who specialize too soon, this becomes a glaring weakness in their aerial game. Fortunately, it is an easy skill to develop with a limited investment of time, energy, and equipment.

Five minutes a few times a week with a partner and some sort of ball (tennis, whiffle, lacrosse, football) is all that is needed. Over-the-shoulder catches like a centerfielder running down a ball hit into the gap should be the end goal, and injecting randomness to the throws is encouraged to allow an athlete to experience varied trajectories and cover different distances.

Relative Strength “Big Three”: Pull-Ups, Dips, and Single-Leg Squats

Too much strength will never be a weakness, but misappropriating time, energy, and precious adaptive reserves to continually pursue strength just might be. Not all strengths are created equal, so it is important to know the demands of your sport. While all sports require a well-rounded approach to both absolute and relative strength development, it is important to know what is most valuable to you and your athletes so you can “lean” accordingly.

For instance, my experience has shown that relative strength is of slightly greater value to my soccer athletes than absolute strength. Conversely, the opposite would likely be true for an offensive lineman in football. I develop and maintain absolute strength for our soccer athletes with conventional squats, deadlifts, presses, and pulls using basic progressive overload principles. Appropriate strength work should supplement on-field movement by enhancing an athlete’s resilience and force-producing capabilities.

Despite being the most general of all forms of preparation, quality strength work should also establish principles that will carry over to more specific iterations of prep such as power and speed exercises. Specifically, posture is critical, particularly as it relates to pelvic position. If the load or speed begins to negatively affect posture, it is dialed back until the athlete is capable.

One of the biggest things I have noticed with soccer athletes is that there is a point of diminishing returns as it relates to absolute strength, but seemingly unlimited performance potential as it relates to relative strength. This is exactly why I chose to highlight pull-ups, dips, and one-legged squats. These specific exercises demonstrate mastery over how well an athlete can move their own body mass and typically present some of the most difficult bodyweight exercises, particularly for young athletes.

One of the biggest things with soccer athletes is a point of diminishing returns as it relates to absolute strength, but seemingly unlimited performance potential as it relates to relative strength. Share on XIn my pursuit of bang for the buck exercises, time invested in these full-body displays of relative strength render the pursuit of more remedial exercises a waste of time (unless, of course, those exercises are in fact an intermediate or developmental step to a pull-up, dip, or single-leg squat). To clarify, I value these three tasks because of their higher degree of difficulty and the innate core stability, balance, and total body awareness necessary to demonstrate them.

More traditional relative strength tests such as the push-up and sit-up test fall short on this front. They could be a means of assistance in the development of the “Big Three,” but not the end goals themselves. I want my athletes to be able to perform 10 strict reps for all the exercises and on both legs for the single-leg squat. If athletes have not yet achieved this standard, keep developing; and if they have, add load.

Sprint

They say to save the best for last, so now I must mention the most delicate and difficult skill to teach: sprinting. The total body coordination and the stress imposed make max effort sprinting the consummate demonstration of athleticism. To optimize effectiveness, sprinting cannot be done haphazardly. Speed work should be done fresh, with full recovery between reps, and reps should last no longer than roughly five seconds.

Full recovery for ATP stores to replenish is widely accepted as one minute of rest for every 10 yards sprinted. Pragmatically, for a developing youth athlete, this is roughly 30-40 total yards of maximum intent, at most. Due to the potency, the total volume of sprints should be limited to approximately 150 yards per session, and sessions should only be administered two to three times a week to push progress, and always done at least once a week to maintain.

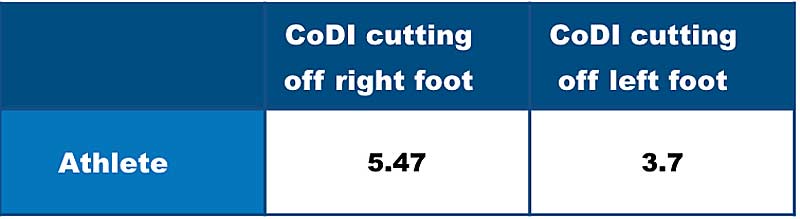

As the ultimate performance enhancer and soft tissue inoculant, the dosage and timing of dosage must to be treated with respect. Speed work should also be objectified to chart progress. For the past two years, I have used Freelap Timing for all our academy athletes’ speed sessions, as well as my personal speed sessions. Freelap is easy to transport and just as easy to quickly set up anywhere. Accuracy and precision are the two most desirable attributes of any tool used for measurement, and Freelap fills the bill on both counts.

The ‘L’ in LTAD

The era in which young multisport athletes were prevalent might be ending; and, in any case, the days of early specialization are likely here to stay. There are many challenges that accompany early specificity in young athletes, but a more imaginative approach to performance training can combat these drawbacks. I have provided specific insight to the limitations I have experienced in working with youth soccer athletes and the methods I have used to try to address those gaps.

There are many challenges that accompany early specificity in young athletes, but a more imaginative approach to performance training can combat these drawbacks, says @houndsspeed. Share on XEvery scenario and sport will have its own subtleties and nuances that require attention, so there is no right or wrong. I am merely encouraging critical thought to fill the voids and supplement accordingly, as I feel strongly it is our job within the performance field to identify and fix problems and not just identify them. I actually look forward to watching the growth and maturation of young athletes who are extra passionate about their craft, as they will push the boundaries of what we thought was possible in each individual sport—that is, provided we do our jobs by keeping them healthy and fully prepared.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Verkhoshansky, Y.V. and Siff, M.C. Supertraining. 1999. p. 264.

Radcliffe, J.C. and Farentinos, R.C. High-Powered Plyometrics. 1999.