The conversation around sleep has become ubiquitous: It’s one of the most important aspects of enhancing recovery and performance, not to mention its benefits for mental processes like memory consolidation. Athletes need to develop sound sleep habits, and we know this.

However, many coaches don’t arm themselves with strategies to help athletes maximize sleep and recovery when life and sports inevitably get in the way of a perfect sleep routine. In particular, we have to take into consideration: athletes play games at night, all but guaranteeing they won’t get to sleep at a decent hour.

Competing late at night causes an influx of sympathetic hormones, like cortisol and adrenaline, while suppressing the secretion of parasympathetic hormones like melatonin.

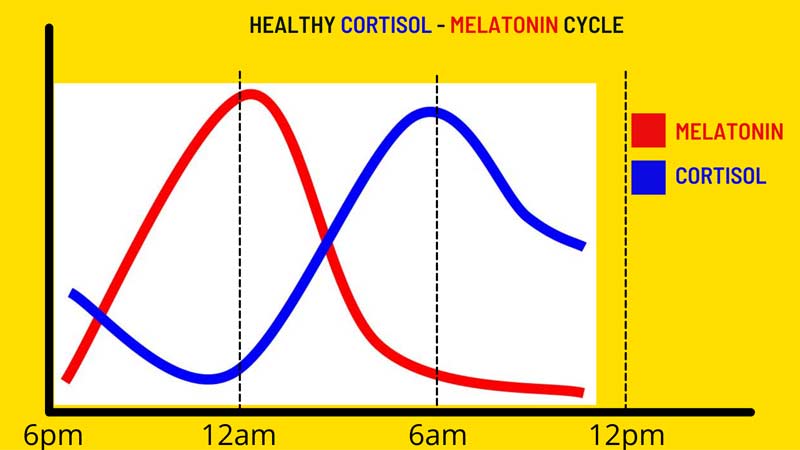

When athletes train in the evening, it elevates sympathetic hormones and suppresses parasympathetic hormones at exactly the time when we want it to be at its lowest—near the onset of sleep. Share on XIn an optimal sleep pattern and circadian rhythm, melatonin rises in the evenings as we prepare for bed and cortisol sinks to its lowest point. When athletes train in the evening, it elevates sympathetic hormones and suppresses parasympathetic hormones at exactly the time when we want it to be at its lowest—near the onset of sleep.

The solution to this would be obvious: Set up schedules with more day games and eliminate late-night practices. However, life and logistics get in the way, and the reality is that sports are usually played at night.

At the highest levels, (NBA, MLB, NHL) athletes need to compete at their best between 7 p.m. and 10 p.m. Combined with the brutal playing schedule, where teams need to play back-to-backs—and three games in four nights—this can lead to chronic issues with sleep and recovery.

This is not just a professional sports issue. College athletes play in the evening as well, and often on back-to-back nights (Friday and Saturday). High school teams often compete in the evening, with schedules that can be dictated by field/facility availability. Youth sports have perhaps the worst schedule of all, as they often have practices scheduled at 7 p.m., 8 p.m., or 9 p.m. several evenings per week, even during a school week.

As performance coaches, we may have some influence over practice times. For the most part, though, game times and travel schedules are largely out of our hands, and it’s our job to take the schedule given to us and make the best of it.

Here are some proven strategies to help athletes recover after nighttime competition and training.

The Post-Game Hormonal State

After a game, sympathetic hormones are rushing through an athlete. Our job is to provide athletes with strategies to shift into a parasympathetic state as swiftly as possible.

Nearly all strategies to induce quality sleep after a game revolve around this concept. Generally speaking, we want athletes to limit activities that cause an uptick in sympathetic hormones and encourage them to make changes that support the flood of parasympathetic hormones.

We won’t be able to completely reverse the downsides of playing sports in the evening. Rather, we do the best we can to get athletes back into a state of relaxation and recovery. As the performance coach, it’s our job to work with our athletes to discuss which strategies will work best for them and their lifestyle, ensuring they’re both accessible and practical.

We won’t be able to completely reverse the downsides of playing sports in the evening. Rather, we do the best we can to get athletes back into a state of relaxation and recovery. Share on XIn my experience, helping athletes make changes starts with educating them on why it’s important and why it matters to them. With adolescent athletes, ask them questions like whether they’re tired during the day after they stay up late after hockey (they likely are). Implant that it’s possible to wake up with energy and feel great, even after late-night games or practices, by making a few changes.

Or, if they’re exceptionally competitive, appeal to how much better they’ll perform in their sport. Ask them to imagine the best they’ve ever felt in their sport—a day where they could do no wrong and they felt great. By improving their sleep, they can always feel like they’re at the top of their game. Ultimately, just like implementing any suggestions to athletes, they have to see what’s in it for them.

Many of these strategies won’t require any technology, although I do recommend athletes monitor their recovery looking at their daily HRV score on their wearable device so they can get a sense of which activities help or hamper their sleep.

Add a Foam Roll (or Massage) Session with Deep Breathing

Foam rolling and deep breathing can increase vagal tone1 and therefore facilitate activation of the parasympathetic nervous system. Right after a game ends, have the foam rollers right there in the locker room so that, as they shower and get ready to leave, athletes can use a few minutes to pair deep breathing with foam rolling. As for quantity, a little bit can go a long way. Thirty seconds is better than nothing. Choose a few body parts that are typically tight after a game (hip flexors, glutes, mid back) and take 3-5 deep breaths per body part.

All told, this will take your athletes less than five minutes, but it’s a key step to shifting to a parasympathetic tone quickly, which will ultimately help the athletes get to sleep sooner and improve the quality of that sleep.

Like foam rolling, traditional massages can also activate the parasympathetic nervous system.2 Even in pro settings, having a massage therapist on hand is a huge luxury, but I encourage athletes who have another person who’d want to give them a massage (like a significant other) to include it as they wind down for the evening.

Deep breathing is a powerful tool, and intuitively I think we all know that if you take a few deep breaths, you’ll instantly calm down and relax. More scientifically, slow, conscious breathing increases activation of our vagus nerve, which in turn blunts the sympathetic nervous system and increases activation of the parasympathetic nervous system.3

After games (assuming there’s no post-game lift), players should pair deep diaphragmatic breathing with a quick foam rolling and stretching session. Share on XAnd, of course, deep breathing is something anybody can do, pretty much anywhere. You can encourage your athletes to do it immediately after competition. While this would help, in my experience athletes will stick to a post-game breathing regimen if they have some structure. That’s why, after games (assuming there’s no post-game lift), players should pair deep, diaphragmatic breathing with a quick foam rolling and stretching session.

Post-Game Nutrition and Sleep

Of course, athletes need to eat. And they need to eat well. Getting to bed 20 minutes earlier at the expense of getting in the nutrition they need is not a good trade-off. However, there are some foods that will harm sleep more than others.

Ideally, at night our digestive tract is slower than normal, and a heavy meal will require our digestive system to work overtime and potentially disrupt sleep.4 But athletes need to eat. A solution to this is to encourage athletes to consume faster-digesting foods.

In a perfect world, this would be a shake. And some athletes can make an absolute beast of a shake that contains all the nutrition they need. However, other athletes—like younger athletes trying to gain weight—need a full-fledged meal. Encourage them to make little shifts toward faster-digesting foods. Choose white rice over brown rice, eggs over steak. Educate them on digestion times of different foods so they can make better decisions. A protein shake can supplement their caloric needs here.

Of course, the nutritional needs of every athlete will vary, but all else being equal, choose the faster-digesting foods.

Manage Blue Light Input

Having a bit of structure immediately after competition will go a long way, but there are still several hours from the time the athletes leave the facility until they go to sleep. During that window, a huge step all athletes should take is to manage their blue light input.

Along with exercise, light entering through our skin and eyes is one of the main regulators of our circadian rhythm. Without getting too deep into a discussion of evolutionary biology, we evolved to be awake and alert when the blue skies were out. On the flip side, with the absence of blue light (and a presence of red lights, like fires), we evolved to shift into relaxation and sleep. The less blue light exposure athletes have after games, the more melatonin will be secreted—which will not only help them get to sleep but help them get higher-quality sleep.

The less blue light exposure athletes have after games, the more melatonin will be secreted—which will not only help them get to sleep but help them get higher-quality sleep. Share on XWith the rise of technology and smartphones, getting athletes to put the phone and other screens away is one of the biggest challenges (especially if you work with high school athletes). Yet, it’s also one of the best steps we can take to help with their recovery.

Here are some specific ideas to help athletes limit blue light exposure after late-night games. Of course, you won’t be able to strictly monitor whether your athletes follow these suggestions or not, so it has to be an ongoing conversation with each one of them.

1. Make sure night mode is on. This one sounds so obvious and so easy. In fact, it is obvious, and it is easy. And yet you’ll be surprised to find out how many of your athletes have the brightness all the way up on their phone right until the moment they go to bed. This is low-hanging fruit, and if you can’t even get your athletes to do this, you have further buy-in problems.

Often, athletes—especially younger ones—will have to be on their devices in the evening doing schoolwork. Without getting into a broader discussion of study habits for young athletes, take the extra few seconds to also put the laptop on night mode.

While night shift mode is a good start, the next level for this is to also turn on grayscale. The grayscale feature also has the benefit of making phones less addicting5, and therefore might help athletes put the freaking things away just because they won’t be continually craving more dopamine hits. Doing these things won’t eliminate blue light, but they are helpful first steps.

2. Encourage athletes to have a screen curfew. A coach won’t be able to enforce this, but it’s the best step for actually eliminating blue light after a game to prepare for bed. Right after a game, the athletes have their night mode and grayscale on. Once they’ve gotten home (or to the hotel room) and had their meal, it’s time to unplug for the night.

To a lot of younger athletes, this can be borderline traumatizing, so you have to offer them alternatives for things they can do in place of being on their phone. Oh, and no—TV is not an option.

Again, you’ll have to work with each athlete to figure out what will work best for them. Of course, factors like schoolwork, home obligations, and—let’s be honest—their social lives may push this back, but help the athlete understand that whenever they don’t need their devices, they should try to put them away. Their social life will still be there in the morning.

As a general guideline, the athlete should aim to put all screens away one hour before they plan on being asleep. So, if they get home at 10:30 (a bit optimistic, but let’s stick with it), and have the goal of being asleep by midnight, then put away all screens at 11.

3. Options for athletes to replace screen time.

-

● Read a Book. Now, getting athletes to read a physical book can be as challenging as nearly anything, depending on the athlete. It arguably deserves its own article. However you go about this discussion, reading is a natural option.

● Journaling. This is one of those new-agey practices that you’ll hear in all the latest self-help books. However, despite this connotation, a journaling practice can help athletes consolidate their memories, stresses, successes, and thought processes, helping them gain a clearer sense of the world, relax their mind, and prepare for sleep.

● Conversation. Ask your athletes if they’ve thought about actually talking to the people they live with. In the case of older professional athletes, this usually means talking to their significant other. Besides the sleep benefits, who knows what kind of positive impact it can have to spend some time talking instead of on screens before bed. Just a thought.

There are limitless options—as long as it doesn’t involve screens, you’ll be helping out your athletes.

Encourage Athletes to Meditate

Meditation is a concept that gets thrown around a lot—and, depending on whether you talk to a neuroscientist or a traditional Buddhist practitioner, you’re going to get very different definitions. You can read more about some the benefits of meditation here, but within the context of sleep, meditation has some interesting research because it can help slow down brain waves, which are a measure of the electrical impulses of the brain6.

While we’re awake, our brain waves are faster than when we’re sleeping. In fact, deep sleep is also called “slow-wave sleep” precisely because our brain waves are their slowest during this phase of sleep.

While meditating, we won’t get into “delta” or slow brain waves, we can leave “beta” (our normal waking brain waves) and enter “alpha” or even sometimes “theta” brain waves through meditation. And then, once we are asleep, we’ll have an easier time getting into deep, restorative sleep. So, not only will meditation help us get to rest, but it can also help us get deeper sleep. And, of course, deep, restorative sleep will be way more valuable to athletes than light sleep.

Not only will meditation help us get to rest, but it can also help us get deeper sleep. And, of course, deep, restorative sleep will be way more valuable to athletes then light sleep. Share on XDoing this in the evening will help shift our brain into relaxation (not to mention meditation also often involves deep breathing). There’s also interesting research that shows meditating at any time of day helps the brain calm down later in the evening. In one study, insomniacs meditated for eight weeks in the afternoon (10 a.m.-2 p.m.); after eight weeks they had improved, suggesting that learning how to relax during the daytime can help people get to sleep at night7.

Strategies to Help Athletes Meditate

Now, it’s one thing to understand the benefits of meditation, it’s another thing—as every performance coach knows—to get your athletes to establish the habit. And meditation, in my experience, has been one of the tougher sells.

But meditation has a benefit that a lot of other aspects of our job—like speed and power training—don’t have: athletes appreciate the benefits much more quickly. But, that’s only if it can click for them. This often begins by breaking down misconceptions surrounding meditation. I often have to explain that it’s not about sitting still for hours on end; it can be as simple as bringing conscious attention to something (like your breath or an object) and then recognizing when the mind wanders from that. Regardless of whether it clicks right away or not, it’s crucial to lower the stakes at first.

Encourage your athletes to set a timer on their phones for just three minutes, and to try to stay aware of their breath. Don’t change it, just notice it. The three minutes will go by quickly. Over a bit of time, you can have them work up to 10 minutes.

By the time an athlete is doing it for 10 minutes and is starting to “get it,” you often won’t have to mention it. They’ll come to you next week talking about how they downloaded a meditation app (like Headspace or Calm) and have been doing it every day.

Smart Supplementation

When it comes to sleep, there’s one mineral that a huge proportion of the active population is deficient in: magnesium. One study showed that 68% of Americans are deficient.8 For athletes, this estimate is likely higher because magnesium is lost through sweat.

Additionally, magnesium is not easy to get through whole foods, so supplementing with it is usually the correct route. However, this gets even more complicated, because most supplemental forms of magnesium aren’t bioavailable, and in fact, they act as a laxative. Rushing for the restroom is not what you want your athletes doing the morning after a game.

Many have made suggestions such as a magnesium cream you can rub on your skin or taking Epsom salt (magnesium sulfate) baths. However, research on whether our body can absorb magnesium through the skin is mixed.9

Another option is to do deeper research on which forms of magnesium are better absorbed in our body. One form that’s showing promise, and in particular brain-health benefits, is magnesium l-threonate. However, these high-quality forms aren’t cheap, so you’ll have to educate your athletes on the benefits and let them make the decision. To avoid serious deficiency, encourage them to eat a few servings of leafy greens each day to cover the bases.

What About Post-Game Lifts?

In the last few years, training after games has become more and more popular among professional sports teams. The logic here is simple: In a jam-packed game schedule, there’s very little time to get quality training in. By training immediately after a game, the athletes have the maximum amount of time to recover from the lift before the next game.

Post-game lifts, though, have the obvious downside of pushing back the athlete’s sleep even further. However, in the professional ranks, these post-game lifts are only 20 to 30 minutes. If you’re organized, you can get a lot of critical training work done in this short time span. And the athletes are already in a heightened sympathetic nervous system state, so they can just stay in a sympathetic state for an extra 20 minutes. Adding a few extra minutes of sympathetic activity to a get a lift in usually makes a lot of sense.

Post-game lifts have the obvious downside of pushing back the athlete’s sleep even further. But if you’re organized, you can get a lot of critical training work done in this short time span. Share on XThe alternative might be to have the team come in early the next morning, which will have its own drawbacks. The third option would be to just not train. As the saying goes, you can’t make an omelette without breaking some eggs, so every option has trade-offs. Depending on the specific schedule, in a lot of cases training right after a game is the best decision.

Immediately after that training session though, have the athletes do what they can to get into a parasympathetic state to jumpstart the recovery process and help them get better sleep. Have the rollers ready and take them through some deep breathing.

Assessing What Works

While I’ve outlined a lot of different strategies here, of course you don’t have to implement all of them with your athletes. Here’s where the art of coaching comes in. It’s your job as a coach to select and gently encourage athletes to try whichever methods will work best for them; this, in all reality, is likely whichever method the athlete will actually stick to.

Second, you’ve probably noticed I didn’t say anything here about getting more sleep. In the busy life and crazy schedule of an athlete, the amount of sleep is obviously important. As performance coaches, that’s often out of our control, and it’s part of our job to help athletes improve the quality of their sleep.

Finally, you’ll want to have a plan to measure and assess whether these changes are effective, so that you and your athletes can see the difference. A simple way to do this is to measure HRV on a wearable device. As I talked about in-depth in this article, HRV pulled while you sleep essentially measures the activity of your parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system. A higher HRV indicates more parasympathetic activity, so you can use the wearable device to track what’s actually supporting the athlete’s sleep and recovery.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Lastova, K., Nordvall, M., Walters-Edwards, M., Allnutt, A., and Wong, A. “Cardiac Autonomic and Blood Pressure Responses to an Acute Foam Rolling Session.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2018;32(10):2825-2830.

2. Diego, M. and Field, T. “Moderate pressure massage elicits a parasympathetic nervous system response.” International Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;119(5):630-638.

3. Bergland, C. “Diaphragmatic Breathing Exercises and Your Vagus Nerve.” Psychology Today. 5/16/17. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-athletes-way/201705/diaphragmatic-breathing-exercises-and-your-vagus-nerve

4. Dantas, R.O. and Aben-Athat, C.G. “Aspects of sleep effects on the digestive tract” (in Portuguese). Arq Gastroenterol. 2002;39(1):55-59.

5. Nield, D. “Try Grayscale Mode to Curb Your Phone Addiction.” Wired. 12/1/19. https://www.wired.com/story/grayscale-ios-android-smartphone-addiction/

6. “Brain waves and meditation.” Science Daily. 3/31/10. Submitted by The Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/03/100319210631.htm

7. “Meditation May Be an Effective Treatment for Insomnia.” Science Daily. 6/15/09. Source: American Academy of Sleep Medicine. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/06/090609072719.htm

8. King, D.E., Mainous 3rd, A.G., Geesey, M.E., and Woolson, R.F. “Dietary magnesium and C-reactive protein levels.” Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2005;24(3):166-171.

9. Gröber, U., Werner, T., Vormann, J., and Kisters, K. “Myth or Reality—Transdermal Magnesium?” Nutrients. 2017;9(8):813.