“The mental side of the game is way over 50 percent, probably about 80.” –Lebron James.

Is meditation the most significant legal performance enhancer available to athletes? From the contemporary mental health movement in the NBA all the way back to the consciousness ceremonies of the ancient Greek Olympic athletes, mindfulness practice and high performance in sports have quite the history together. Today, many athletes and everyday individuals are keeping this tradition and turning to their desired form of meditation practice for optimal health and performance, and a higher quality of life in general. With a growing trend of mindfulness turning more mainstream day by day, it’s time to explore how and why athletes should recruit mindfulness practices for gains on and off the court, field, and track.

Lessons from Pro and Elite Athletes

To the uninitiated, meditation may seem like a quasi-religious practice and in “woo-woo” territory. While some practitioners may also adopt these iterations of mindfulness practice, the reality is that these practices are more variations of what meditation is biologically: a software update that fine-tunes your operating system (brain and nervous system) back to the way it’s meant to function. The truth is that meditation is not some far-off enchanted land only visited by the enlightened. Not at all, in fact.

Meditation can certainly be developed and cultivated with certain processes, as seen in various iterations such as transcendental meditation. While exploration of various mindfulness practices and flow-state methods should be encouraged, the essentialist view here is to simply dial back and be. The practice can literally be as simple as sitting in a room with your eyes closed and engaging in conscious breathing.

For both athletic development and quality of life, it’s worth introducing your athletes to various forms of mindfulness practice, says @coopwiretap. Share on X“It may sound silly, but just closing my eyes in a dark room and breathing for 10 minutes a day helps me,” says Marcus Morris, forward for the Boston Celtics.

Let’s address the elephant in the room before reading any further.

I understand the difficult path a coach has to understand their role here. You don’t want to overstep your boundaries and force something on someone. I get that. But the reality is that in addition to developing athletes, we also try to leave them better off as people in general. Meditation addresses both. The mentoring part of coaching is still important. You don’t have to force anything on anyone, but for both athletic development and quality of life, it’s worth introducing your athletes to various forms of mindfulness practice.

The Neuroscience of Your Brain’s Operating System

Upgrading athletes’ software might sound like something out of a dystopian science fiction movie, but in a funny sort of way, that’s what it does. Both a simple toe dip and a deep dive into neuroscience research can demonstrate the positive effects of meditation on the brain’s nervous system complex. Research and testimonies from the trenches both illustrate these physiological morphs being a key ingredient in performing at a high clip.

Both a simple toe dip and a deep dive into neuroscience research can demonstrate the positive effects of medication on the brain’s nervous system complex, says @coopwiretap. Share on XThis field of neuroscience gives some credence to the long-held esoteric belief that the mind and the physical body are linked. This is exciting news for athletes and coaches alike. Don’t get me wrong—we aren’t at the point where we can fully unweave the rainbow. We may never be, but we are at least at the point of being able to illustrate morphological changes in the physical body.

Brain imaging techniques, biofeedback, and other biomarkers have shown statistically significant improvements in response to continuous meditation practice. The brain’s adaptability—or neuroplasticity—to epigenetic training inputs is now understood to be fluid for a much longer period of time than originally thought. This is encouraging not only for tactical strength and conditioning items like motor skill acquisition, but also for rewiring the brain and nervous system complex of athletes for mental performance.

In adults, meditation has cultivated adaptations in the brain such as increased gray matter concentration within the left hippocampus, the cerebellum, the temporo-parietal junction, and the posterior cingulate cortex, to name a few. These are key areas involved in learning, memory, perspective adoption, empathy, sense of self, and emotional regulation. It’s not hard to tease out how this could impact an athlete’s confidence, next-play mentality, presence, kinesthetic presence in the body, and recovery from stress to better accommodate the eustress of training for better adaptations.

Mindful Muscle: Successful Program Implementation

Before delving any further, it’s worth addressing how to successfully implement meditation in your private practice or organization. While there is no right answer, there are definitely ways to go and not go about the process.

At a bare minimum, helpful suggestions and highlighting the importance of meditation individually and/or in a group setting is a good idea. This gets away from any force feeding and instead is a further demonstration of the level of care in your practice. It lets the athlete know they are more than their stats and that their long-term well-being is a top priority, though there are certainly performance downloads to be had.

I find that with younger student athletes, having rapport with parents helps—I inform and ask permission of the parents of high school athletes prior to having the conversation. At a minimum, these younger (and even collegiate athletes) may respond best to meditation apps in the beginning. Some of these are even slanted toward athletic performance, which helps enable trust and buy-in for the uninitiated.

I also find that a group seminar session can be incredibly impactful. This “selling” through education empowers the athlete to make the decision, while also giving you a platform to speak on the supporting research and benefits to be had.

My colleague, Mike Franco of the Dallas Mavericks, represents something of a growing trend in the NBA. While the concept of sports psychologists is nothing new, Mike is a mental performance skills coach who leans heavily on meditation as a tool for player transformation. Having worked with athletes at a variety of levels, Mike echoes the above sentiments and treats the process as a fundamental extension of player development and training:

“Working on your mindset is a skill set, just like working on the physical parts of your game. For the physical skills, we might work on shooting, in-game reads, and strength and conditioning. I look at this the same—it’s a skill. You need to be able to be in the moment, play present, stay focused, control emotions, and take confident action every play, no matter what. Really, it’s just about not stopping yourself.”

Meditation helps players unlock parts of their game, while also leaving them better off as people—something we should all strive for in our own practices, says @coopwiretap. Share on XMike currently works with first-year players, as well as at the G-league affiliate, The Texas Legends. He not only helps develop players, but also implements meditation protocols to help fresh faces adjust to all of the life changes that playing at the professional level demands. The resultant effect is helping players unlock parts of their game, while also leaving them better off as people—something we should all strive for in our own practices.

What Can Go Wrong with an Athlete’s Brain

In addition to basic meditation iterations, sometimes stronger, more neurogenic interventions are warranted. In the contemporary meditation space, there’s a propensity to stop at meditation and positive-think your way through things. While this is immensely powerful on its own, it’s still important to feel and thus look at the big picture, addressing the entire nervous system. In reality, athletes may require more kinesthetic, somatomotor interventions to truly perform at their best.

The best places to start with this research are the behavioral neurology being done at Huberman Lab in the Bay area, somatic processing science, and the biology of early life trauma. In essence, we all have had some type of traumatic event or period of high stress happen to us. This isn’t to say that all athletes have PTSD-level trauma, but perspective is what constitutes trauma, not the event itself. This traumatic event or period of high stress leaves a biological imprinting at the neurological level. This imprinting can then come back to haunt you in periods of high arousal, such as athletic performance. Allow me to elaborate.

As an example, let’s say an athlete (Jim) was picked last on the playground and this was traumatic and altogether embarrassing for him. In these type of cases, certain neural firing combinations associated with survival light up—often the amygdala and xiphoid nucleus responsible for fear, threat detection, and stress. The kicker is that, obviously, Jim survived or else he wouldn’t be playing basketball right now.

However, the forebrain projects meaning onto experience. So, if these distress-bringing neural firing combinations lit up in the face of Jim’s performance as a child and he survived as far as the brain is concerned, then guess what? There’s a solid chance that—prompted with similar triggers—Jim’s nervous system lights up and potentially sabotages his performance. This performance anxiety is neurogenic and often has to be trained with kinesthetic components in addition to baseline meditation.

The book, The Body Keeps the Score, is an easily digestible, consolidated reference for a deeper dive into this research, but it’s also worth looking at the rodent studies on functional neurology. Scientists have observed these qualities in rats during last man standing simulations. In essence, two rats were on a platform meant for one. The rat that won the first time by knocking his opponent off then went on to win over 80% of the time, all things being equal on a physical level. Observations of brain patterns echoed these neural “glitches.”

The boomerang here is that sometimes athletes will need interventions that reprogram the mind-body interface, neurologically speaking. This can be as simple as free breathwork practice or as advanced as biofeedback.

Athletes sometimes need interventions that reprogram the mind-body interface, neurologically speaking. This can be as simple as free breathwork practice or as advanced as biofeedback. Share on XAuthor and former pro basketball player Witalij Martynow likes to use a collection of tools ranging from targeted breathing techniques to neuro-linguistic programming to help basketball players and other athletes perform at their highest ability. At the most basic level, he sees a need for players to be able to manage autonomics. “‘Excess’ sympathetic fight/flight/freeze response can negatively impact your game. We can consciously reverse that response with diaphragmatic breathing.”

Be it in a time-out or an in-game situation, it’s important to give your athletes a basic tool to switch stress response, slow down heart rate, and get into “flow states” (the zone) with conscious breathing. Being able to control your neural real estate is invaluable and as simple as strong nasal inhales with elongated, parasympathetic exhales (though many valid breathing techniques can work).

Your Body Speaks Its Mind

Occasionally, you’ll find athletes who have more significant “blocks,” find themselves in confidence valleys, and/or have severe performance anxiety independent of skill level. In these cases, it can be useful to refer out and recommend somatic processing or biofeedback techniques.

These techniques work on trigger-associated sensations, responses, and reflex arcs of the interconnected webs of the nervous system and respective subsets, including autonomic, peripheral, somatic, and enteric. These therapies include EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing), TRE (trauma release exercise), neurofeedback, sound therapies, trauma body work, and beyond. All of these have the end goal of integration, meaning the ability to process and reassociate various parts of the nervous system for the purpose of elevated quality of life and performance.

These therapies have an end goal of integration, meaning the ability to process and reassociate various parts of the nervous system to elevate quality of life and performance, says @coopwiretap. Share on XMammals have the ability to shake themselves free of neurogenic trauma. For example, if you see a deer cross the road and almost get hit by a car, it violently shakes itself to rid the effects of stress from the physical body. Athletes and all humans have lost their way to engage this mechanism as easily, so these therapies exist to recapture this natural adaptive response.

One of my favorite techniques for self-study homework in athletes is TRE, which was first introduced to me by health coach Ryan Frisinger. TRE is a manual technique for reproducing this mammalian reflex in humans. The contemporary TRE movement has been ushered in by Dr. David Berceli. While what grabs the headlines has been its effects on veterans’ PTSD, much work has been done for athletes and physical performance enhancement. I find that after a fluid period of time, athletes have the ability to self-induce when needed, to a degree, not unlike the aforementioned deer example.

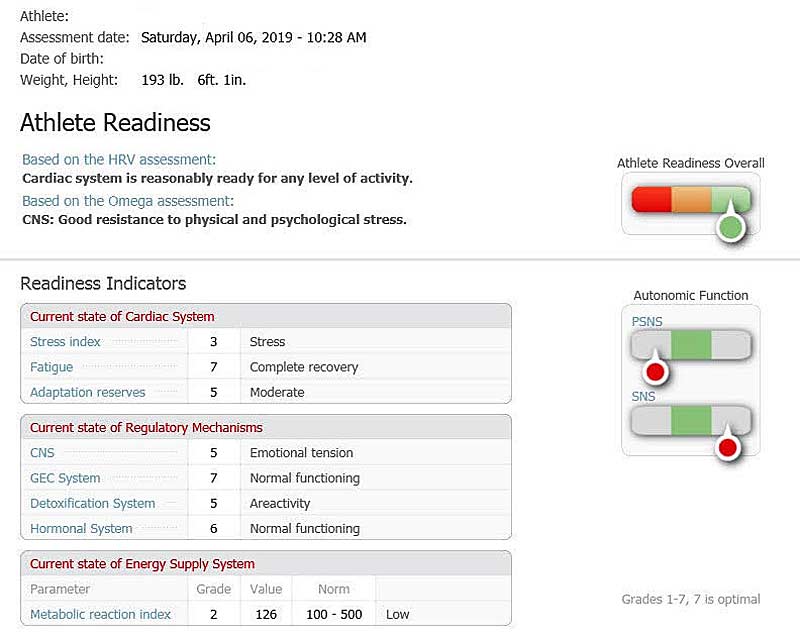

For me, personally, the net impact has been measurable in optimizing athletes’ health in some key biomarkers (Omegawave, Biostrap, biofeedback, labs), in subjective drops in performance anxiety, and also enhanced sport performance.

I personally refer out for most of these therapies, though I have found it helpful for me and Ron Acevedo to have sound therapies, syntonics, and neurofeedback helmets in-house for athlete needs. For athletes who claim to have trouble with mindfulness practices and/or can’t go see a practitioner, it has helped to be able to tackle this at a biological level while also respecting the athlete’s right to privacy.

The Brain’s Protect-to-Perform Continuum

In applied neurology, you’re taught that the brain works on a protect-to-perform continuum. This is also a major crux underpinning popular movement therapy schools, such as Reflexive Performance Reset, Postural Restoration Institute, Neurokinetic Therapy, and NeuFit.

The basic idea is that if your brain is shifted onto the protect side of things, you won’t be able to fully neurally express your maximum potential on the performance side of things. In his book, The Other 80, Witalij Martynow and Metta World Peace bring to light both sides of this spectrum in athletes.

The physical side of this is quite interesting. One potential manifestation of being shifted into the protect mode is limited neuromuscular function or diminished access to activation potential of certain muscles. This not only has implications on performance issues, but also on injury pathologies. When I see an athlete who is stressed, it almost always takes more work to get their movement prep work and corrective exercises to take effect or last. This is also where having the luxury of the direct current electrostim device, Neubie, greatly helps me to expand the central nervous system’s reach to the peripheral working muscle groups.

This can also play a role in rehabilitation. I’ve mentioned before that if a basketball player has an injury and their brain is still in the mode that they can only survive, say, a 20-inch landing, then their vertical is likely to be around that height. BUT if you can shift this into more of a perform continuum (e.g., tools like the Neubie, meditation, breathwork, etc.), then you can dissolve these central governors (limiters) and the athlete will be better able to express maximal intent. In this context, that vertical goes up right away in most cases.

In research on tension myositis (or myoneural) syndrome, also known as mind-body syndrome, it is taught that the brain is responsible for pain pathway generation and various tissue qualities, including stiffness and pliability. While training absolutely affects these, it really is a complex interplay of these inputs (nutrition, too), that can lead you down positive or negative roads. In some cases (and as referenced by Martynow), this can go as far as your brain injuring you to “protect” you from some perceived onslaught.

An extrapolation of this is to critically look at your weightlifting methods and identify which exercises place the athlete’s brain in a mode of bracing and survival (“protect,” e.g., heavy barbell back squat) vs. performing (e.g., sprinting). I think it’s fair that strength coaches should keep this in mind when performing a needs analysis. I suggest evenly splitting your exercises between ones that target loading benefits, such as metabolic and hormonal distress for muscle hyperplasia, and ones that target performance benefits for primarily neural adaptations.

Evenly split your exercises between ones that target loading benefits and ones that target performance benefits for primarily neural adaptations, advises @coopwiretap. Share on XClosing the loop, it’s important to keep this in mind when assessing athletes, prescribing exercise selection, implementing corrective exercises, practicing breathwork, and setting meditation protocols. You need to look at the holistic picture in an alchemical sense, instead of guessing and checking.

A New Look into the Flow-Like Experiences of Athletes

A better understanding of athletes and their neural circuitry means a better understanding of the default mode network (DMN). The DMN is your body’s predictable resting state patterning that your brain drifts into when at rest. Unfortunately, this unengaged state is also where worrying, anxiety, and ruminating tend to coexist. Originally discovered in fMRI studies, the DMN is one of the most abstract networks of the brain.

Based on interpretations of the latest research, what we know is that the more an athlete is engaged with a task, the less activated this resting cognitive state is. Mindfulness meditation, breathwork, and many of the referenced mind-body interfacing techniques help to quiet the DMN to help support a more optimal state for the athlete to perform in. However, you can also have some other novel techniques in your pocket for athletes.

Looking at the work of leadership consultant David Rock, it’s important to create dedicated practices, interventions, and settings for your brain to evolve out of the DMN. For coaches, this can mean dedicated time spent implementing games out of training, fun focus training (e.g., pattern recognition), and/or implementing game scenarios by which the athlete has to fully engage with the task.

Could this perhaps be one of the reasons why training methods that require the athlete to fully engage and exert themselves—like sprinting, isoinertial resistance, or performance isokinetics—seem to work so well beyond the physical adaptations? I can’t say for sure, but it’s an interesting concept to ruminate.

Meditation in the Trenches

Hopefully, I haven’t lost you with that last exploration. I would like you see this article for what it is: an anthropological piece on meditation, mindfulness, and basic neuroscience for both athlete and coach. Much of what has been discussed underpins the surface level we all see discussed by athletes such as DeMar DeRozan, Kevin Love, and more. Even if all of this is a little new or “woo-woo” for you, it’s easy to appreciate the “Zen Master,” Phil Jackson, implementing meditation with Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant, and his organizational culture. At the very least, you can’t argue with the results.

I see meditation and mindfulness practices as an extension of showing the human being behind the athlete, says @coopwiretap. Share on XRather than subscribing to one dogma, it’s important to educate athletes and invite them to do their own n=1 experimenting to discover what works best. I see meditation and mindfulness practices as an extension of showing the human being behind the athlete. You might just find some one-of-a-kind gains on and off the court.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Always been a huge fan of hypnosis and meditation to focus the mind, I remember the 400m sprinter Ewan Thomas started using when he was 47 runner.

Over recent years I personally have used a track from Simon Capon https://amzn.to/2DV3q1I that works great.