Tom Dos’Santos is a Ph.D. student in Sports Biomechanics at the University of Salford, U.K., where he is investigating the biomechanical determinants of performance and injury risk during change of direction. Dos’Santos has published approximately 40 peer-reviewed journal articles and is a certified strength and conditioning specialist (NSCA). He has previously worked as a strength and conditioning coach in soccer, netball, rugby, lacrosse, and BMX. He currently consults on strength and movement profiling with professional rugby and soccer teams in Greater Manchester and is a co-creator of the science of multidirectional speed.

Freelap USA: The penultimate step is of great importance for coaches to understand change of direction. Often, we read the research but need a good explanation of what the role of that step is for redirecting an athlete. Can you share a simple definition for us and explain why it’s important to know how that step works?

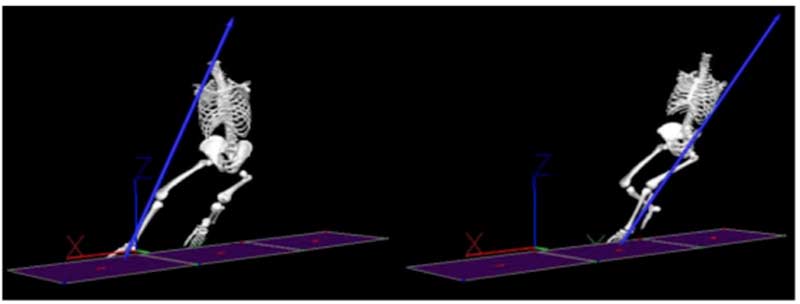

Tom Dos’Santos: Changing direction is a multistep action1 and the penultimate foot contact (PFC) plays a major role in facilitating such actions. The PFC is defined as “the 2nd to last foot contact with the ground prior to moving into a new intended direction”16 (figure 1), and it serves two primary functions depending on the change of direction (COD) scenario, angle of COD, approach velocity, and physical capacity for that athlete:

- Positional/Preparatory Step – to facilitate an effective whole-body position for effective push-off during the main COD foot contact (i.e., final foot contact (FFC)).

- Braking Step – to reduce momentum prior to push-off during the FFC (typically for CODs of sharper angles >60°, but dependent on the COD scenario, approach velocity, angle of COD, and athlete physical capacity).

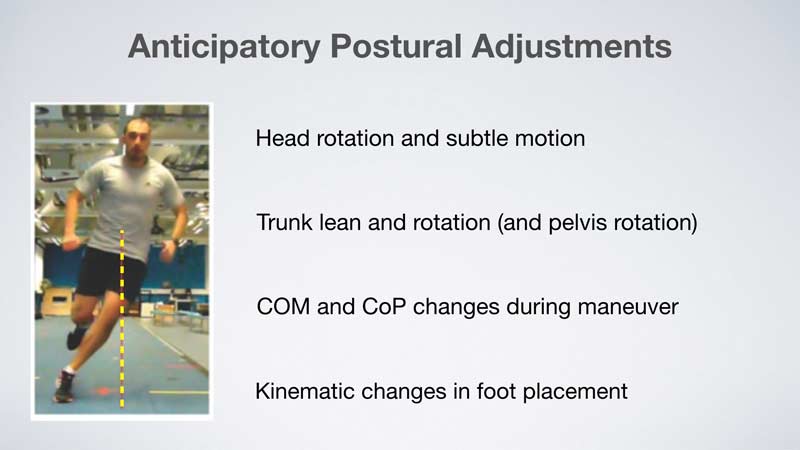

During COD, athletes typically initiate the directional change one or more steps prior to the main COD foot contact. This is known as an anticipatory postural adjustment. These postural adjustments typically include kinematic changes in foot placement, trunk lean and rotation (and pelvis rotation), and head rotation. As shown in figure 2, by typically pre-rotating the step prior to the main push-off (FFC), it helps reorient the whole-body center of mass (COM) toward the intended direction of travel, thus reducing the redirectional demands of the FFC and facilitating faster performance13.

For sharper directional changes (i.e., 90° cuts and 180° pivots), the PFC also plays an important role as a preparatory step by positioning the whole-body COM for effective push-off during the FFC. For example, in a 505 agility test, you athletes go through rapid knee, hip, and ankle dorsiflexion to lower the COM. This is performed in a rotated position to reorient the COM toward the intended direction of travel, again reducing the redirectional demands during the FFC. This then puts the athlete in a favorable position for effective push-off during the FFC.

When performing COD actions, athletes typically reduce their velocity (i.e., momentum) prior to changing direction. As approach velocity and angle increase, athletes need to reduce their momentum over the PFC, and potentially over a series of steps prior to the FFC, in order to perform the intended angle COD, which we describe as an angle-velocity trade-off18. Based on the literature, it appears that for CODs ≤ 45°, PFC braking forces are limited, and velocity maintenance is key (though the PFC is still important for effective body positioning). However, for CODs >60°, the PFC plays an important role in braking and, undoubtedly, preliminary deceleration is needed. It is worth noting that with greater approach velocities, distances, and angles, preliminary deceleration will occur over a number of foot contacts.

Results from research show that PFC-dominant braking strategies (i.e., maximizing and emphasizing horizontal braking force) could be one way to help improve COD performance14,19,21 while reducing injury risk16,19. From a performance perspective, by braking earlier during the PFC (and potentially steps prior):

- We increase braking impulse, which leads to a reduction in horizontal momentum of the COM.

- This then allows more effective weight acceptance and preparation for the drive-off phase of the directional change and can allow the FFC to emphasize propulsion rather than braking. This also results in a shorter ground contact time (a key determinant of faster performance).

- Greater PFC braking forces are associated with faster 90° and 180° COD performances.14,19,21

From an injury perspective, PFC-dominant braking strategies may help alleviate knee joint loads during the FFC.16,19 Knee joint loads have the potential to strain the ACL and, when high enough, can result in rupture. Emphasizing braking during the PFC is a safer strategy compared to the FFC because:

- PFC braking is typically performed in the sagittal plane, where we can utilize the strong hip and knee musculature, and the ground reaction force (GRF) vector is more aligned with the knee joint (though athletes should ensure strong frontal plane alignment).

- The knee goes through greater knee flexion range of motion (PFC 100–120° versus FFC 20–60°), which equals greater angular displacement. Thus, based on the work-energy principle, ↑ work = greater reduction in kinetic energy and ↓ velocity.

- We reduce FFC GRF and subsequent knee joint loads in FFC—the limb that gets injured during COD actions.

- Crucially, ACL injuries occur ≤ 50 ms, which provides insufficient time for postural adjustments (neuromuscular feed-forward mechanism). Thus, reducing momentum is critical for reducing knee joint loads and potential ACL strain.

A review article we have published presents technical guidelines for coaching the PFC.16 Hopefully, coaches understand the importance of the PFC as a preparatory and braking step.

Freelap USA: The isometric mid-thigh pull is growing in popularity here in the U.S., for good reason—it’s safe and valid in determining an athlete’s peak force and rate of force production. Can you share why you feel the test has so much value in sports performance?

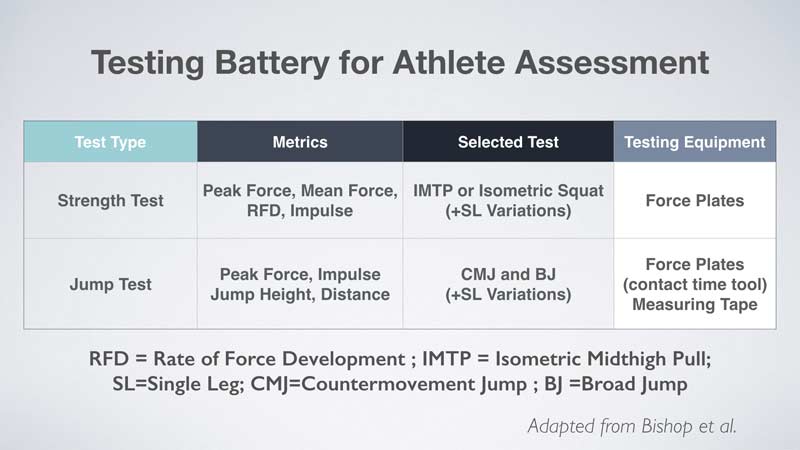

Tom Dos’Santos: As the ability to apply force over time intervals (i.e., impulse) underpins movement (i.e., change in velocity), and greater strength (i.e., the ability to exert force) is typically associated with superior dynamic performance (during numerous athletic tasks) and potential injury mitigation, practitioners are interested in methods to evaluate the rapid and maximal force production capabilities of athletes. The isometric mid-thigh pull (IMTP) is a fantastic assessment for evaluating the rapid and maximal force production capabilities of athletes when the testing and data analysis are performed correctly! I strongly encourage coaches to read and follow the recommended testing and data analysis guidelines that we have recently published9.

In comparison to traditional 1RM testing, which requires skill and can be a time-consuming and fatiguing process with the potential risk of injury, IMTP testing is simpler, safer, and a more time-efficient method (typically 5–8 mins to test one subject) that induces less fatigue. Importantly, strong associations have been observed between IMTP peak force (PF) and 1RM back squat, deadlift, and weightlifting performance; thus, the IMTP could be used as a potential surrogate to 1RM testing9.

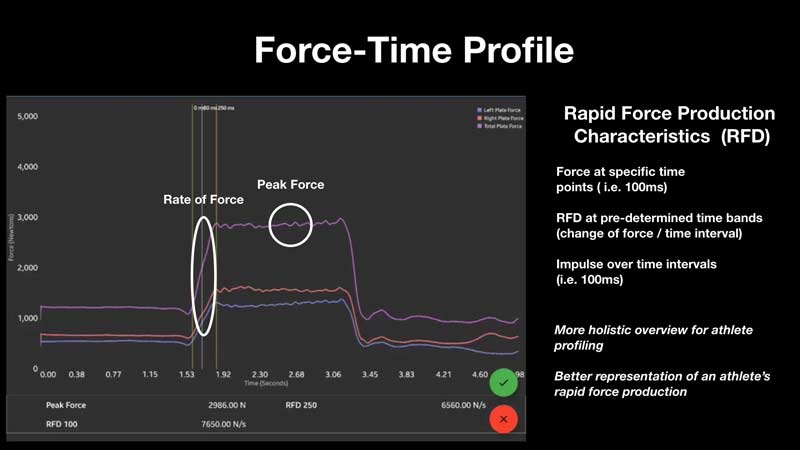

The critical advantage of IMTP testing is it allows examination of time-limited force expression variables, such as time-specific force, RFD, and impulse over time intervals. Share on XThe critical advantage of IMTP testing, however, is that not only can maximal force production be attained from the vertical ground reaction force data (i.e., peak force) collected from the force plate, but time-limited force expression variables can also be examined, such as time-specific force, rate of force development (RFD), and impulse over time intervals, typically 30–300 ms (figure 4). Being able to examine these rapid production characteristics is significant, and arguably more important than maximal force production, because of the time constraints to express force rapidly during sprinting, jumping, and COD.

During IMTP testing, a force-time curve is generated and, subsequently, we can create a “force-time profile” for our athletes (figure 4) that we can use for strength diagnostics and profiling, setting benchmarks, and talent identification. The key variables of interest include PF, time-specific force, RFD, and impulse over specific time intervals (i.e., 30–300 ms), as shown in figure 4. Specifically, PF has demonstrated high within- and between-session reliability measures across a range of different athletic populations7, and time-specific force values appear to provide the best reliability measures compared to RFD and impulse9,15. RFD, impulse, and time-specific force variables provide similar information; thus, I recommend practitioners inspect time-specific force values along with PF, due to the better reliability measures.

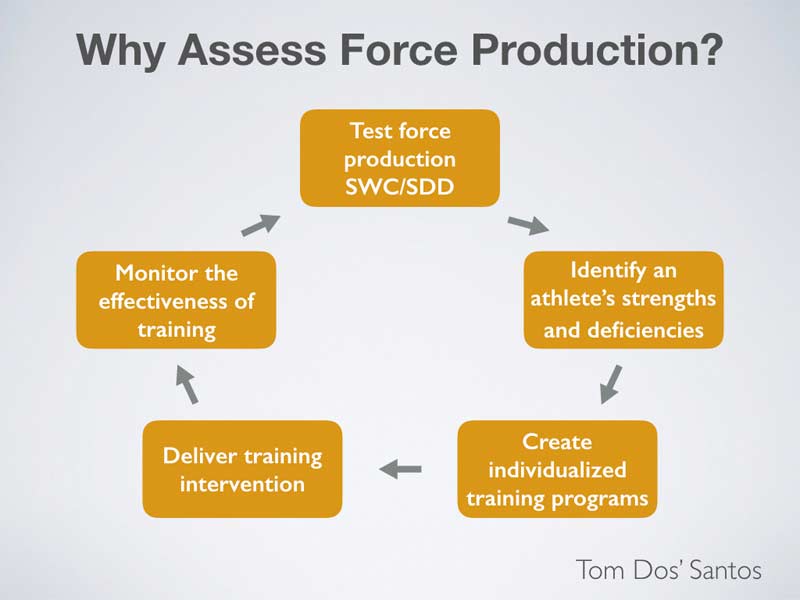

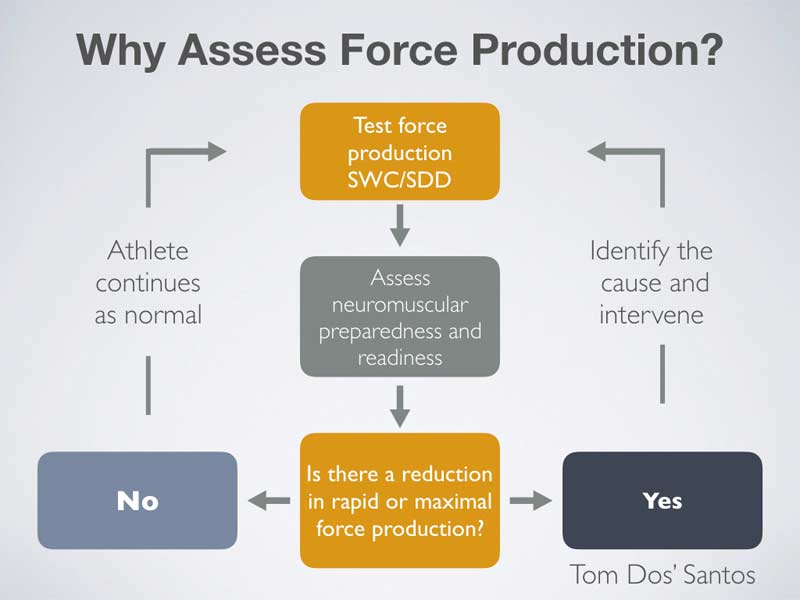

The aim of strength and conditioning is to shift the force-time curve up (i.e., magnitude of force) and to the left (rate of force development), and the IMTP directly allows practitioners to identify strengths and deficiencies so that we can create individualized training programs. We can monitor the effectiveness of training interventions by reassessing IMTP force production (under standardized conditions) and determining whether the changes are greater than the smallest worthwhile change (SWC) or smallest detectable difference (SDD) (figure 5). We can continually go through this process throughout our mesocycles and macrocycles.

The IMTP directly allows practitioners to identify strengths and deficiencies so that we can create individualized training programs, says @TomDosSantos91. Share on X

Finally, we can also use the IMTP to assess neuromuscular preparedness and training readiness.24 As illustrated in figure 6, practitioners may consider using the IMTP as a neuromuscular preparedness/training readiness tool prior to sessions to identify athletes who may be displaying reductions in maximal or rapid force production characteristics. This reduction could potentially be viewed as “fatigue,” and, thus, practitioners can delve deeper by identifying the cause and devising strategies to overcome the “fatigue.”

It is stressed that if practitioners are going to use the IMTP as a neuromuscular preparedness assessment, they should follow three recommendations:

- Establish their own between-session reliability measures.

- Select a variable that will be sensitive to change.

- Establish individual SWCs/SDDs to determine “real” changes in performance.

Norris et al.24 recently found that PF was not meaningfully suppressed post Australian rules football (ARF) matches (up to four days) and that RFD 0–50 milliseconds and 100–200 milliseconds were variables more sensitive to changes (i.e., reductions) post ARF matches (2–4 days).

Freelap USA: The change of direction deficit is a practical and simple test for coaches. Knowing that most strength coaches still struggle to get access to technology, how can they use simple timing gates and software to get more out of 5-10-5 tests?

Tom Dos’Santos: As we are all aware, an assessment of COD performance based on completion times that only use timing gates is heavily biased toward faster athletes22, and the COD deficit has been developed to provide a more isolated measure of COD ability that is not biased toward faster athletes17,23. This can be simply calculated by subtracting the COD completion time by a linear speed time of the equivalent COD test distance. The commonly used method for calculating COD deficit is: 505 completion time – 10-meter sprint time. These tests commonly feature in testing batteries for most practitioners and sports, and subsequently require very little effort to calculate (as you have already collected the data).

As it is advantageous to be equally proficient at changing direction rapidly from both limbs, I encourage practitioners in their COD assessments to first examine COD performance from both limbs to establish if any athlete displays a performance deficit when turning/COD from either limb. Doing this can help inform future training for that athlete.

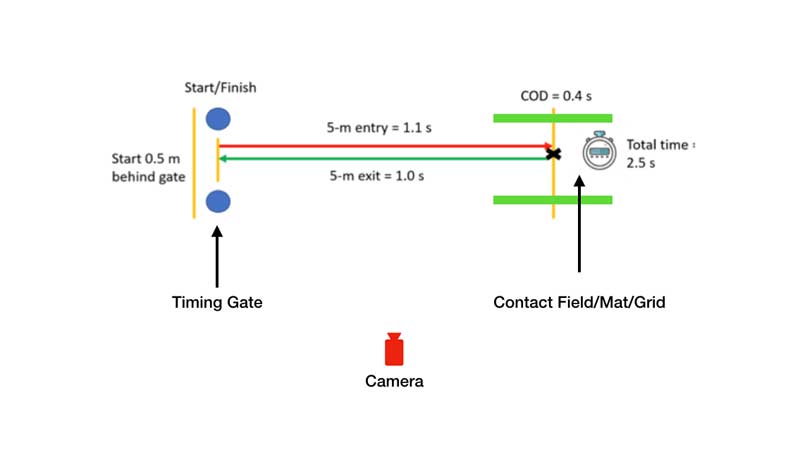

I encourage practitioners to first examine COD performance from both limbs to establish if any athlete displays a performance deficit when turning/COD from either limb, says @TomDosSantos91. Share on XNext, practitioners with access to contact mats, OptoJump, or other software that can be synced with timing gates could gather a lot of information during the 505, 5-10-5, or other COD speed assessments. Rich Clarke has recently been at the forefront of devising simple strategies to gain more insight into COD and deceleration ability during tasks such as the traditional or modified 505 (figure 7), and I recommend that coaches read his posters and presentations on his ResearchGate profile.

If we look at figure 7, Rich Clarke suggests that we could obtain more information regarding the entry profile prior to the COD (red arrow), COD ground contact time (black cross), and exit profile (green arrow), by syncing timing gates with a contact mat, OptoJump, etc.

In the hypothetical example above, an athlete performs a modified 505 in 2.5 seconds. We can divide this total time into three components to gain better insight into how they achieve the time:

- Entry time (red arrow). Duration from athlete crossing start timing gate (first break of beam) to touchdown of the COD at the turning line = 1.1 seconds (1st split time).

- COD (black cross). Duration from touchdown of COD to toe-off of the COD (performed at the turn line) = 0.4 seconds (2nd split time).

- Exit time (green arrow). Duration from end of COD GCT to athlete crossing the finish timing gate = 1.0 second (3rd split time).

By applying this method, the practitioner can gather more information on how the total time was achieved and determine where an athlete’s strengths and deficiencies are in terms of deceleration, COD GCT, and reacceleration. They can then use this to inform future training. It is worth noting that I have adapted Rich Clarke’s method, as he adds 50% of COD GCT to the entry and exit times and does not include COD GCT in terms of his profiling.

Personally, I think it would be beneficial to divide the total time into the three components, but it is the discretion of the practitioner as to which method they apply, as long as analysis procedures are standardized longitudinally when monitoring changes. Irrespective of method, the process outlined in figure 7 could be applied to the traditional 505 (as Rich Clarke has done), the 5-10-5, or cutting tasks.

Finally, for coaches who do not have access to timing gates, Carlos Balsalobre-Fernandez has developed and validated the COD timer app, which uses the high-speed video capabilities of a smartphone to film COD tests2. Carlos has initially validated the app for modified 505 COD speed tests. This simply requires the coach to stand perpendicular to the start/finish line, film the trial using a smartphone, and manually select the start, touchdown, and toe-off of the FFC, and finish. Consequently, the coach obtains total time and GCT for the COD.

I believe Carlos is working on updating the app to encompass the entry and exit times that Rich and I have discussed, which would be a great addition. A video outlining how to use the COD timer app is presented below.

Video 1 (here). Carlos Balsalobre-Fernandez has developed and validated the COD timer app, which uses the high-speed video capabilities of a smartphone to film COD tests.

Freelap USA: The dynamic strength index is a crude ratio but some coaches like it because it’s simple to calculate. Can you go into the pros and cons of this metric?

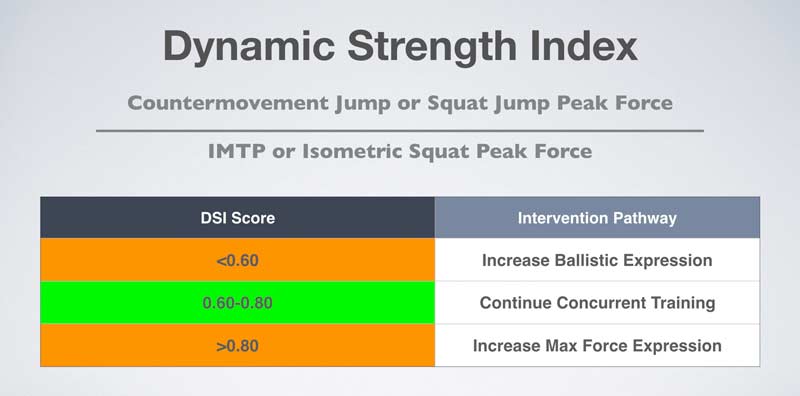

Tom Dos’Santos: The dynamic strength index (DSI), also known as the dynamic strength deficit (DSD), is a combined assessment method that examines the ratio between dynamic (ballistic) propulsive PF (i.e., squat or countermovement jump) and isometric PF (i.e., IMTP or isometric squat) for the lower limb, and the ratio between dynamic bench press throw PF and isometric bench press PF for the upper limb25,26. For the purpose of this section, I will focus on lower-limb DSI, but we are essentially assessing how much of an athlete’s strength potential can be expressed dynamically.

The key aspect of the ratio is that it is used to assist in the profiling and training prescription for an athlete. As shown in table 1, Shepperd et al.25 suggests an athlete displaying a ratio <0.60 would warrant training emphasis on ballistic force expression, >0.80 would warrant training emphasis on maximal force expression, and 0.60–0.80 would warrant a combination of ballistic and max force expression training.

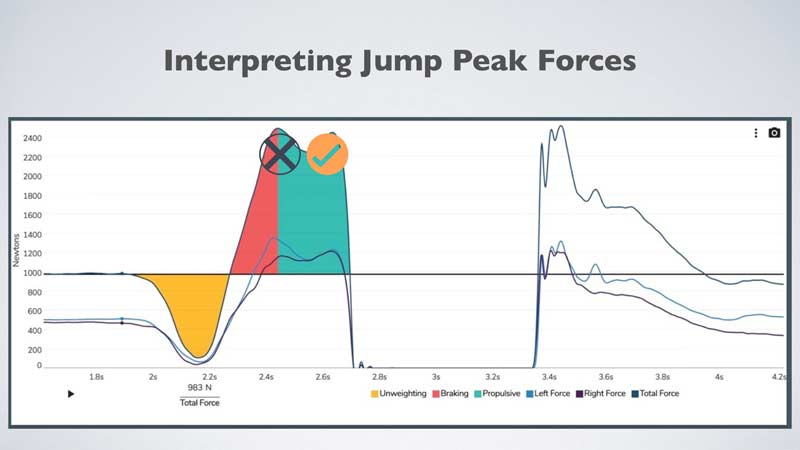

As coaches’ testing batteries commonly include jump and isometric strength assessments, this ratio would require very little effort to calculate. We have shown that better between-session reliability measures are obtained when using CMJ PF versus SJ PF10, most likely attributed to the CMJ being easier to standardize and perform. However, it is imperative that coaches ensure they are using PF during the propulsion phases of the CMJ, not the braking phase. This is extremely important for athletes who may display bimodal CMJ force-time profiles, as illustrated in figure 8.

Furthermore, athletes can also alter their CMJ strategies to alter their force-time characteristics, which coaches should be aware of. Verbal cues can affect force-time characteristics; thus, it is imperative that CMJ instructions are consistent longitudinally. Typically, “jump as fast and as high as possible,” is common practice and produces reliable measures.

Additionally, I prefer IMTP testing to isometric squat testing. In my experience, athletes dislike driving up against a fixed immovable bar during isometric squatting due to the spinal compression. Irrespective of testing method, coaches should be conscious of the method of obtaining DSI when comparing values to normative data across the literature.

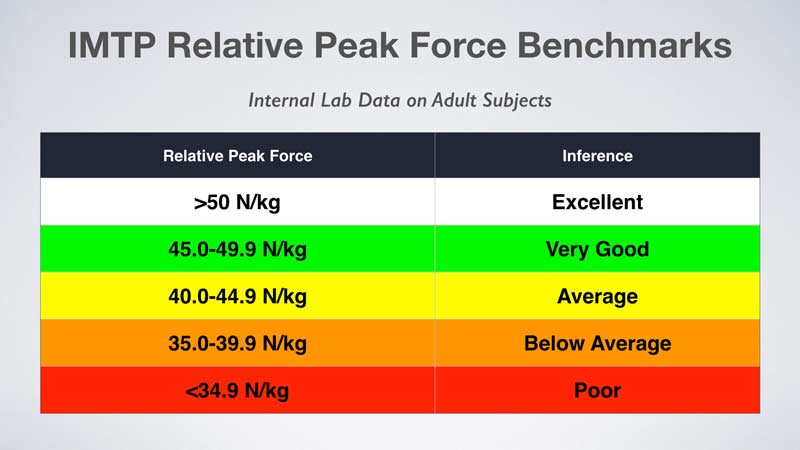

A significant limitation of the DSI is that it is only a ratio, and interpretation of the ratio alone could lead to incorrect evaluations. For example, an athlete may display a ratio of 0.6 (CMJ PF = 18 N/kg / IMTP PF = 30 N/kg), and based on the ratio alone, they would warrant combination training. However, inspection of the IMTP PF indicates that the athlete is relatively weak (based on relative IMTP data from our lab–table 2) and would most likely benefit from getting stronger (i.e., developing maximal force expression)11,27. Thus, I advise caution when looking solely at ratios, and I strongly encourage coaches to look at the absolute values of the two components (i.e., CMJ PF and IMTP PF) for a more holistic overview.

Alternatively, I suggest practitioners examine relative IMTP PF to decide if an athlete warrants emphasis on maximal or rapid force expression. Table 2 provides some benchmarks from our lab (i.e., inclusive of BW). If an athlete achieves very good to excellent scores for IMTP relative PF, they would benefit from shifting their training emphasis to rapid force production. If they do not hit these benchmarks, I suggest targeting maximal force expression.

Additionally, I encourage coaches to examine additional variables, not just DSI, when profiling their athletes. Variables such as RSI during a 10/5 or DJ and inspecting alternative variables for CMJ testing such as jump height, time to takeoff, and subsequently RSI mod can be used for profiling and to assist in the training prescription for an athlete.

Freelap USA: Asymmetries are complicated to manage, as there are natural differences between right and left. What can youth or academy coaches do to help screen out problems but not overreact to differences in leg power? What do you think is a good approach to get a practical assessment in place for high school athletes ages 14–18?

Tom Dos’Santos: An inter-limb asymmetry is simply a difference in performance or function of one limb with respect to the other4, and it can be categorized into strength (force asymmetries—i.e., IMTP PF) and skill asymmetries (i.e., difference in COD time between left and right limb)20. Before I discuss the methods and processes for assessing asymmetries, we first must look at the bigger picture and question whether being asymmetrical is a problematic issue. Currently, there is no clear consensus that an athlete with greater strength asymmetries (i.e., PF, impulse/ power deficits between limbs) will display inferior athletic performance and is predisposed to increased risk of injury.

There is currently no clear consensus that an athlete with greater strength asymmetries will display inferior athletic performance and is predisposed to increased injury risk. Share on XThe issue with strength asymmetries is that they are task- and metric-dependent, with the magnitudes of % imbalance inconsistent across tasks (e.g., isokinetics typically have a greater % imbalance than IMTP PF), and metrics within the same task (e.g., IMTP PF % imbalance < impulse % imbalance)3,28. Additionally, the directions of asymmetry are also task- and metric-dependent3,28. For example, an athlete may display superior IMTP PF on their right limb but display greater concentric knee extensor strength during isokinetic assessments for the left limb. This issue has been excellently highlighted by Chris Bishop and Chris Thomas in recent work investigating strength asymmetries in team sport athletes, and it shows the difficulty in diagnosing a consistently dominant and stronger limb.

Personally, I would be more concerned about an athlete’s coordination and skill asymmetries in performance during dynamic tasks; for example, examining inter-limb asymmetries in jump-landing mechanics, COD performance, etc. I would argue that athletes displaying suboptimal landing mechanics for their left limb are of greater concern than a 15% imbalance in IMTP PF, which is only reflective of that one muscle quality during that specific task. Nevertheless, when exploring strength asymmetries, there is a whole range of tests available, as outlined excellently by Chris Bishop6 in table 3 below.

While looking at strength asymmetries can be insightful, there are a whole range of factors that we must consider. Once the coach has chosen their tests (and acknowledged the task-dependent nature of asymmetries), we must decide how to calculate and determine a meaningful imbalance between limbs. Chris Bishop and Chris Thomas have done some great work in this area, and there are a whole range of equations that you can use to calculate a % imbalance or ratio.

Importantly, the different equations result in different % imbalances (which may alter your evaluation)4. Bishop et al.5 has recommended the use of this equation—assessments % imbalance = (D-ND)/D×100—for unilateral, with D and ND referring to stronger and weaker limbs, respectively. Additionally, for bilateral assessments, this equation has been proposed: % imbalance = (D-ND)/total of left and right limb×100.

Next, the difficulty is how to define a meaningful imbalance between limbs. Currently, there is no consensus across the literature for an asymmetry threshold, with various methods employed. A 10–15% imbalance has generally been considered a meaningful asymmetry; however, there is very little evidence to support this. Coaches may consider comparisons to normative data or adding the mean % imbalance and SWC for their group of athletes to define an asymmetry threshold.

It has been recently suggested that in order to establish a “real” asymmetry between limbs, the difference must exceed the variability/error (% imbalance = 10%, % CV = 5%). However, in order to be confident that a real asymmetry is present, I would suggest establishing the between-session reliability to see if the % imbalance and direction of asymmetry are consistent. For example, does an athlete displaying 15% greater IMTP PF on the right limb also display the same imbalance for the right leg 48/72 hours later? If an athlete does not consistently display a similar % imbalance for the same leg, I would caution against defining an athlete as asymmetrical and ask coaches not to overreact in this situation.

If an athlete doesn’t consistently display a similar % imbalance for the same leg, I would caution against defining an athlete as asymmetrical, says @TomDosSantos91. Share on XAs stated earlier, the issue with strength asymmetries is that they are task-dependent and can vary between tasks (i.e., athlete right limb dominance for IMTP PF but left limb dominant for CMJ propulsive impulse). Additionally, the metrics during the same task, such as an IMTP, can also fluctuate in terms of limb dominance. Furthermore, Bishop et al. has also highlighted that the magnitudes and directions of asymmetry are not necessarily consistent between sessions3, longitudinally over a season, and they are also sensitive to post-match fatigue (24/48 hours)8. These issues are problematic and can lead to different evaluations being made in terms of an athlete’s asymmetry profile and potentially erroneous conclusions that could lead to incorrect training prescription.

Finally, the major issue to consider is that asymmetries are simply a percent or ratio, and, as I stated regarding DSI, we must also take into account the absolute values and compare these values to some normative data/benchmarks. For example, an athlete may be strong and asymmetrical, but their weaker limb still outperforms the rest of the squad. Alternatively, you may have an athlete who is symmetrical but weak and the worst performer for that metric in the squad.

When monitoring changes in asymmetries, I not only advise coaches to inspect the % imbalance, but they must consider the direction of asymmetry (i.e., an athlete may still have a 10% imbalance, but the dominance has changed from left to right). More importantly, they must also inspect the absolute values because an athlete can reduce their % imbalance by the dominant limb becoming weaker while maintaining strength in the non-dominant limb.

Ideally, we’d want athletes to be symmetrical in terms of force production and skill. However, there’s evidence that simply getting athletes stronger can reduce strength asymmetries. Share on XIn an ideal situation, we would want athletes to be symmetrical in terms of force production and skill. However, there is evidence that simply getting athletes stronger can reduce strength asymmetries12. Generally, I would concentrate my efforts on getting athletes stronger and to a high strength level (i.e., 1.5–2×BW squat/ IMTP PF 45 N/kg) before overreacting and specifically targeting force asymmetries. Conversely, I would argue skill asymmetries are a problematic issue, and every effort should be made to correct such imbalances in landing mechanics, COD ability, etc. between limbs.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Andrews JR, McLeod WD, Ward T, and Howard K. “The cutting mechanism.” American Journal of Sport Medicine. 1977; 5: 111–121.

2. Balsalobre-Fernandez C, Bishop C, Beltrán-Garrido JV, Cecilia-Gallego P, Cuenca-Amigó A, Romero-Rodríguez D, and Madruga-Parera M. “The validity and reliability of a novel app for the measurement of change of direction performance.” Journal of Sports Sciences. 2019; 37(21): 2420–2424.

3. Bishop C, Read P, Chavda S, Jarvis P, and Turner A. “Using unilateral strength, power and reactive strength tests to detect the magnitude and direction of asymmetry: A test-retest design.” Sports. 2019; 7(3): 58.

4. Bishop C, Read P, Chavda S, and Turner A. “Asymmetries of the Lower Limb: The Calculation Conundrum in Strength Training and Conditioning.” Strength and Conditioning Journal. 2017; 38(6): 27–32.

5. Bishop C, Read P, Lake J, Chavda S, and Turner A. “Inter-limb asymmetries: understanding how to calculate differences from bilateral and unilateral tests.” Strength and Conditioning Journal. 2018; 40(4): 1–6.

6. Bishop C, Turner A, Jarvis P, Chavda S, and Read P. “Considerations for selecting field-based strength and power fitness tests to measure asymmetries.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2017; 31(9): 2635–2644.

7. Brady CJ, Harrison AJ, and Comyns TM. “A review of the reliability of biomechanical variables produced during the isometric mid-thigh pull and isometric squat and the reporting of normative data.” Sports Biomechanics. 2018; 1–25.

8. Bromley T, Turner A, Read P, Lake J, Maloney S, Chavda S, and Bishop C. “Effects of a competitive soccer match on jump performance and interlimb asymmetries in elite academy soccer players.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2019.

9. Comfort P, Dos’Santos T, Beckham GK, Stone MH, Guppy SN, and Haff GG. “Standardization and Methodological Considerations for the Isometric Midthigh Pull.” Strength and Conditioning Journal. 2019; 41(2): 57–79.

10. Comfort P, Thomas C, Dos’Santos T, Jones PA, Suchomel TJ, and McMahon JJ. “Comparison of methods of calculating dynamic strength index.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 2018; 13(3): 320–325.

11. Cormie P, McGuigan MR, and Newton RU. “Adaptations in athletic performance after ballistic power versus strength training.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2010; 42(8): 1582–1598.

12. D. Bazyler C, A. Bailey C, Chiang C-Y, Sato K, and H. Stone M. “The effects of strength training on isometric force production symmetry in recreationally trained males.” Journal of Trainology. 2014; 3(1): 6–10.

13. David S, Mundt M, Komnik I, and Potthast W. “Understanding cutting maneuvers – The mechanical consequence of preparatory strategies and foot strike pattern.” Human Movement Science. 2018; 62: 202–210.

14. Dos’Santos T, Thomas C, Jones AP, and Comfort P. “Mechanical determinants of faster change of direction speed performance in male athletes.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2017; 31(3): 696–705.

15. Dos’Santos T, Thomas C, Jones PA, McMahon JJ, and Comfort P. “The Effect of Hip Joint Angle on Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull Kinetics.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research: Published ahead of print, 2017.

16. Dos’Santos T, Thomas C, Comfort P, and Jones P. “The Role of the Penultimate Foot Contact During Change of Direction: Implications on Performance and Risk of Injury.” Strength and Conditioning Journal: Published ahead of print, 2018.

17. Dos’Santos T, Thomas C, Comfort P, and Jones PA. “Comparison of change of direction speed performance and asymmetries between team-sport athletes: application of change of direction deficit.” Sports. 2018; 6(4): 174.

18. Dos’Santos T, Thomas C, Comfort P, and Jones PA. “The effect of angle and velocity on change of direction biomechanics: an angle-velocity trade-off.” Sports Medicine. 2018; 48(10): 2235–2253.

19. Graham-Smith P, Atkinson L, Barlow R, and Jones P. “Braking characteristics and load distribution in 180 degree turns.” Presented at Proceedings of the 5th annual UKSCA conference, 2009.

20. Maloney SJ. “The Relationship Between Asymmetry and Athletic Performance: A Critical Review.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research: Published ahead of print, 2018.

21. McBurnie A, Dos’ Santos T, and Jones PA. “Biomechanical Associates of Performance and Knee Joint Loads During a 70-90° Cutting Maneuver in Sub-Elite Soccer Players.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research: Published ahead of print, 2019.

22. Nimphius S, Callaghan SJ, Bezodis NE, and Lockie RG. “Change of Direction and Agility Tests: Challenging Our Current Measures of Performance”. Strength and Conditioning Journal. 2017; 40: 26–38.

23. Nimphius S, Callaghan SJ, Sptieri T, and Lockie RG. “Change of direction deficit: A more isolated measure of change of direction performance than total 505 time.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2016; 30: 3024–3032.

24. Norris D, Joyce D, Siegler J, Clock J, and Lovell R. “Recovery of Force-Time Characteristics After Australian Rules Football Matches: Examining the Utility of the Isometric Midthigh Pull.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 2019; 14(6): 765–770.

25. Sheppard JM, Chapman D, and Taylor K-L. “An evaluation of a strength qualities assessment method for the lower body.” The Journal of Australian Strength and Conditioning. 2011; 19(2): 4–10.

26. Suchomel TJ, McMahon JJ, and Lake JP. “Combined assessment methods.” Performance Assessment in Strength and Conditioning, 2018.

27. Suchomel TJ, Nimphius S, Bellon CR, and Stone MH. “The Importance of Muscular Strength: Training Considerations.” Sports Medicine. 2018; 48(4): 765–785.

28. Thomas C, Comfort P, Dos’Santos T, and Jones PA. “Determining bilateral strength imbalances in youth basketball athletes.” International Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017; 38(9): 683–690.