An ongoing argument among coaches these days revolves around the issue of transference. Those who have delved into this subject may also know it as dynamic correspondence, and Dr. Verkoshansky is credited with initially using this concept to classify exercises. The five criteria he used serve as a gauge to determine transference:

- Same muscle groups

- Same range of motion

- Same type of muscular contraction (regime)

- Emphasis of a portion of the ROM

- Magnitude of force and duration applied

Examining this deeper, it’s not an all or nothing proposition but rather a classification process that can help coaches determine the “degree” of transference. This is evident in Bondarchuk’s “complex” system, where a training program encompassed exercises of high transference (CE/SDE) to lower transference (SPE/GPE).

Even though this sounds complicated and can prove to be a time-consuming endeavor, Dr. Michael Yessis (creator of the 1×20 system) broke it down into three categories, where most coaches can see their exercise sets in the gray areas:

- That the exercise duplicates the same neuromuscular pathway as seen in execution of the competitive skill.

- That the exercise develops strength over the same range of motion as it is displayed in execution of the competitive skill.

- That the exercise duplicates the same type of muscular contraction as seen in execution of the competitive skill. 1

For those of us working with young athletes in their critical developmental stage, the path of simplicity, efficiency, and frugality is in high order. Our goals are to drive improvement at a low cost and leave room for progress during a high-performance stage. Given that field and court sport athletes are best served by developing the major qualities of speed, power, change of direction, and strength in congruence, our exercise selection should give us a bang for our training buck. Regarding the athletes I discuss in this article, I’ll reveal how we drove improvements in speed and power markers with general training that covered a broad spectrum.

We can drive improvement at a low cost and leave room for progress during a high-performance stage using high repetition and low load, single-sets. Share on XFor me, the discovery of high repetition and low load, single-set exercises validated the effectiveness and efficiency of this method—especially when training the year-round athlete who has limited developmental time and reserve capacities due to the demands of their sport. Here, we’ll delve into the broad spectrum of transference that general exercises have on multiple athletic qualities. This is a follow-up to my post on applying velocity based training in the 1×20 system.

Quality I: Power Measures

I’ll begin with power measurements but won’t go on and on about how broad jump and vertical jump improvements are correlated to athletic performance, as these are well known. I’ll explain how improving the basic ability of power not only underpins the quality at which we do our sporting movements, but also bridges the gap of a strength exercises to applicable movement.

The quality of power production (and absorption) is particularly evident in a sport such as soccer with the many cutting and start and stop actions in pursuing or defending the ball:

In order to make a change in direction while in motion, especially a quick one, you must have adequate levels of strength (eccentric, concentric, and isometric), speed-strength (explosive strength), flexibility (ROM) and coordination (technique). Also included is speed of movement which is related to your strength levels. 2

For optimal projection to occur, the muscles of the hip, knee, and ankle must absorb, stabilize, and contract in a quick, powerful, and coordinated manner. I understand that the transfer of more specific drills (plyometrics, altitude drops, etc.) plays a vital role in the development of these movements, but these means incur a high cost if the athlete is not prepared. In other words, our athletes are only as strong as their weakest link—especially among an over-competed and under-trained population such as women soccer players.

Establish a base of preparedness from general means in the developmental stages with the foresight of preparation for a high-performance model. Share on XThe way I see it, coaches must develop needs sequentially: establish a base of preparedness from general means in the developmental stages with the foresight of preparation for a high-performance model. Even though both of the young women featured in this article are Division 1 signees, their base athletic metrics were at a relatively low level.

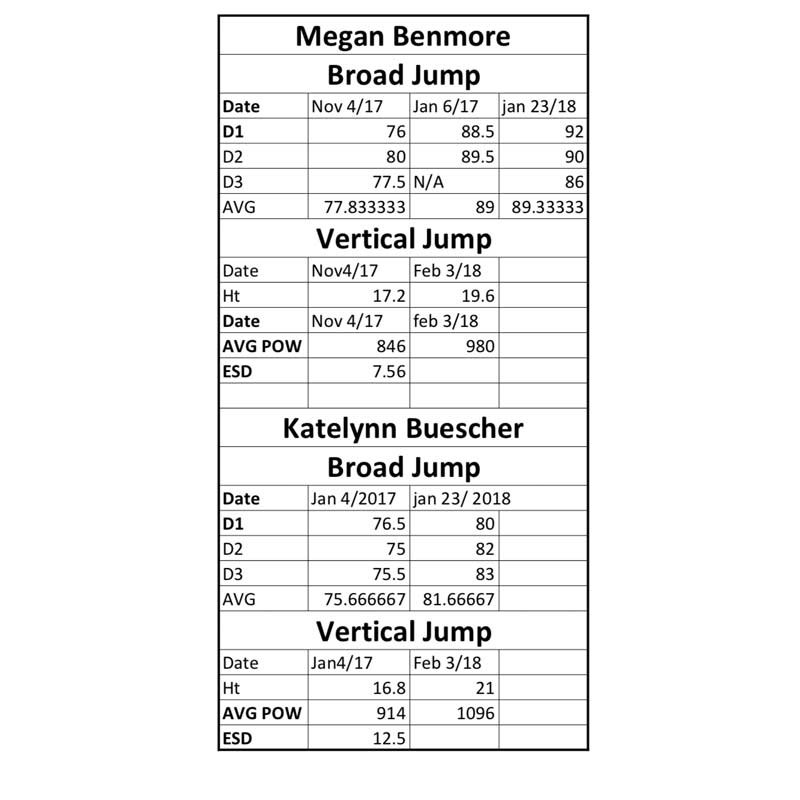

As you can see, both athletes made substantial progress over the respective time periods, especially in the broad jump. The beauty of using BABA (Build A Better Athlete system, a.k.a., 1×20) was two-fold. Performing one high-rep set for broad-spectrum (general) exercises helped build strength along the repetition spectrum. It also gave us time to work on other aspects of athleticism without draining the neuro reserves. These included cutting technique, sprinting, specialized exercises, and variations of broad and vertical jumps.

Side Note: This phenomenon became even more evident as Meg and Katelynn had their early morning team “conditioning” requirements as well as side jobs that included babysitting and shoveling snow for multiple hours a day. Jeff Moyer mentioned circumstances like these in his TFC presentation covering “strength as a spectrum,” as he explained the “why” behind the minimal effective dose philosophy.

What’s also interesting are the improvements in average power, a metric that includes jump height in relation to body weight. There are two ways to look at these improvements:

- Jump height remains relatively unchanged as body weight rises, which applies to athletes looking to put on quality muscle mass. This scenario mainly pertains to athletes in weight-class-dependent sports looking to bump up a class or two as well as underweight footballers or rugby players. I don’t believe in gaining weight at the sacrifice of our power production capabilities.

- Body weight remains relatively unchanged while vertical jump (countermovement style) rises, which applies to our athletes in this scenario. The low exposure to total volume (and time under tension) in this minimal dose, broad-spectrum strategy helped keep their body weights unchanged.

- Yessis also referred to the 20-rep sets as strength-aerobic, in which the cardiovascular system is stressed via cardiopulmonary response. Remember the old Super Squats program by Randall Strossen? Your heart would be beating out of your chest and you’d be breathing hard by rep 10.

- Capillarization is also a hypothesized effect where the growth of new BVs occurs.

- Aerobic style training is typically associated with mobilization of fatty acids, which may help keep a lean physique.

- The effect of Henneman’s size principle with this method lends itself to FT fiber growth without the risk of heavier loads.

The total volume remained stagnant (20-rep sets in the half squat), as each exercise was executed for the same amount of reps aiming at improving technical execution of the jumps and specialized exercises while making minimal increases in load in the strength exercises from week to week. This is unlike classic strength approaches in the West, where overall barbell loads (volume and intensities) and the number of exercises increase over time. While this approach may be optimal for those in barbell sports or the gym rat who wants to work out longer and harder, it will most likely eat away the adaptive reserves of those who merely need to use strength to develop athletic abilities.

Quality II: Agility

Devoting time to the specialized drills and jumping exercises (while sparing the adaptive reserves) was imperative to bridge the gap between our strength exercises and “on-field” work. While these young women improved their strength, they simultaneously learned how to apply that strength without running the well dry.

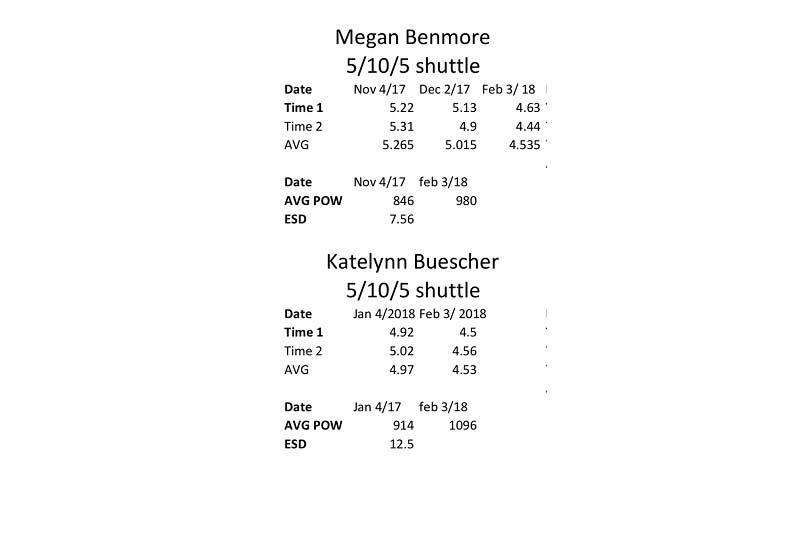

As you can see, both young women made great progress in the basic 5-10-5 test. Note that I did not introduce the specialized exercises for the side and forward cord lunges until the second week of January (these are described in the many resources provided by Dr. Michael Yessis and better shown in the Coaches Corner video section of the CVASPS Community site). This may be why we saw the larger improvements in Megan’s time from December to February. Part of this decision was two-fold:

- I felt Meg needed to develop strength in the spinal erectors, abductors, and adductors

- My comfort level with teaching the exercises, which was made easier with the videos on the CVASPS Community site (excuse my shameless plug for Jay DeMayo)

In hindsight, I probably would have introduced the lunges in a more basic manner with dumbbells, or possibly isometric holds, to make a smoother transition into the cords. Still, there is nothing wrong with the progress we made. Here are my takeaways on how we did this.

First: The protocol of half squats was not simply doing a set of 20. While I may get flack for this, I used a form of triphasic modalities in two warm-up sets preceding the 20-rep set (what we call our push set). The importance of eccentric strength in cutting cannot be understated, as it’s a key strength skill (a coordinated strength effort) in executing effective change of direction movements.3 I waved the method of slow-lowering to the half squat position (for a six-count), holding the half squat position (for a six-count), and slow lowering with a bottom hold (each for a three-count). We did this in three-week waves.

My reasoning here was for them to learn the position, posture, and pace of the pattern (apologies for the tongue twister). The loads represented fifty and seventy-five percent (respectively) of the load in the push set, which was just enough to prime them for it. In the grand scheme, loads this light may not have been sufficient to completely train eccentric or isometric qualities enough. But, given the training age of the athletes, I felt it was necessary to use the TP method as a learning tool to effect posture and position more than anything else.

Some may ask: Why the half squat? In short, a really smart guy in Whitewater Wisconsin told me in a phone conversation that half squats transfer to cutting and quarter squats transfer to sprinting, referencing the Rhea paper about joint angle specific adaptations.4

Second: As mentioned previously, the ability to spare training time and the nervous system allowed us to develop technique simultaneously. Below are a series of pictures at the “plant point” of a cut.

From this perspective, you can see a couple of things that stand out as inefficient. First, her head and shoulders are in front of her hips (center of mass). Second, her hips are closed, not turned, and are too late in positioning her body to run in the opposite direction. The lack of strength in her erector muscles is evident as her torso angle dips into her shin angle. The lack of position causes her head and hips to swing around her plant foot as she pushes off, which forces her lead foot to swing back and to the side roughly at a 45-degree angle from her intended direction (as marked by the circle), detracting from the sharpness of the cut.

In this case, her lack of technique and postural strength force her to lose a step in the direction she wants to change to.

Notice the more balanced and centered posture in the picture above, along with a pretty good hip turn. You can also see that Meg’s lead foot is more perpendicular to the plant foot as well as “in the air,” ready to receive the ground off the push-off. What used to take Meg two movements (and more time) to execute now takes a single movement. Look at the torso and shin angle—nearly perfectly parallel and into that ankle beautifully—so she can now apply the developed strength optimally.

Quality III: Confidence

I believe I heard Joe Kenn say in one of his presentations that “confidence transfers,” and this is a quality often overlooked in developing young athletes. It’s easy for us coaches to get lost in the numbers, but if there’s one intangible I’ve learned in this project, it’s that if we can measure, we can motivate. These two things go hand in hand, giving both coach and athlete an idea of where we’re going together and giving both equal ownership in the progress made.

If there's one intangible I've learned in this project, it's that if we can measure, we can motivate. Share on XGratification is a great thing, both as an athlete and coach: it keeps us in check with the athlete on the intent of effort, and for the coach, it pushes us on the critical thinking end. I believe it was Tony Holler who wrote in a recent article (or one of his million twitter posts per day) about a dopamine release when kids see their numbers. If this is true, is this not the neuro-rich environment we want our kids in? Hell yes, I say—because if they can see it, we can sell it! All this talk about buy-in is made simple.

In working with this pair of female athletes thus far, they’ve given me a hard time about having to go pants shopping because their legs had grown out of their current size. I, of course, joked, “As if you two ever needed another excuse to go shopping?!” This type of interaction is vital in relationship building. My young eighth-grader (whose numbers were not featured in this article as her training is mostly to garner technical competence and basic strength) has also experienced a similar confidence boost.

Recently, she scored a goal while playing as a defender during her indoor season—since she was on a shorter pitch, she was able to score from a long-distance kick. She and her parents were surprised and elated, and her mother told me that she would never have had the confidence to attempt that type of shot before. A couple of weeks later, her father told me how she now pursues offensive attacks with her arms up, unafraid to engage with larger players as she plays a level up against high schoolers. With that said, it’s hard to argue with the positive effects of a minimal effective dose approach that does not bash our kids into some archaic and ass-backward mantra of no pain, no gain.

For the private sector coach, this outcome is imperative, as keeping steady improvements throughout your time with athletes will make for a more enjoyable training experience—which also keeps parents and coaches happy.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Michael Yessis, PhD. “What Is Dynamic Correspondence?” SportLab (blog).

2. Michael Yessis, PhD, “You Must Have Adequate Levels of Strength (Eccentric, Concentric, Isometric),” in Women’s Soccer: Using Science to Improve Speed, (2001, Wish Publishing), pg 47.

3. Michael Yessis, PhD, “Strength Along with Coordination Is Very Important, Especially Eccentric Strength,” in Explosive Basketball Training, (2003, Coaches Choice), pg 130.

4. Matthew R. Rhea, et al. “Joint-Angle Specific Strength Adaptations Influence Improvements in Power in Highly Trained Athletes,” Human Movement 17, no.1 (March 2016): 43-49.