The field of athletic development and sport preparation often undergoes audits via the latest fads, trends, and paradigm shifts. Lately, many successful coaches have moved toward low dose, optimal dose, minimal effective dose, or insert your term here dose. This is especially true among the coaches I’ve been fortunate to interact with and listen to in the past three years. During that time, I attended the Track and Football Consortium (TFC), where Jeff Moyer outlined the idea of strength as a spectrum and how to execute that in a program such as the 1×20 system—a concept that stood out to me.

At TFC and conferences like it, the information often leaves one’s head spinning…in a good way! Each presentation has nuggets of gold and diamonds in the rough, and Jeff’s presentation contained both. In this application, strength training is one component of many that need to be trained in an athlete’s toolbox.1

In a practical sense, a coach who has limited time to train his athletes (as many of us experience) needs to find a way to effectively and efficiently make improvements in the key indicators that matter. Spending time executing multiple sets and reps of multiple strength exercises not only takes time away from learning vital skills but also the athlete’s recovery and adaptation reserves. In other words, you can only run the well dry so long before you run out of water.

General Physical Preparation? Try Broad Spectrum Preparation

In Moyer’s words, “twenty rep sets are one of the least possible CNS costs to get a positive transfer.” The phase of 20s is also paramount to building a young athlete’s broad spectrum of needs, which include strengthening connective tissues, cardiovascular development, and capillarization of blood vessels, skill improvement, and maximal strength— all within a single set. Sounds like a way to get a bang for your buck.1

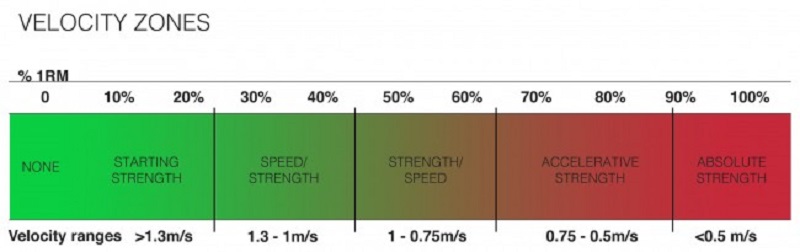

All this got me thinking: How can I see or show this? In his TFC presentation “A Minimalist Approach to Building a Better Athlete,” Moyer mentioned that the 20s cover a spectrum of strength, including:

- Accelerative strength

- Strength endurance

- Maximal strength

It also includes immense carryover to power metrics, such as vertical jump, broad jump, and sprinting. The great thing about trends is that sometimes they produce nifty little tools. Enter velocity measuring devices!

I decided to measure the spectrum of reps in a twenty-rep set and see how these fell along the velocity zone-special strengths chart. In this case investigation, I used Open Barbell V2.0 and the accompanying IOS app in the ½ squat exercise with a pair of female soccer players.

A Mini-Case Study

As chance would have it, I had two perfect candidates to apply this idea with immediately after the conference—two female collegiate soccer players, Meg and Kate. Like many soccer players, they had a lot of experience and hours on the pitch, but only a brief training history consisting of pre-season work (meaning endless low speed running) with their high school team. Meg also had a short period of basic work with me before entering this system. At the time, both were entering their senior seasons and looking forward to Division 1 collegiate careers.

This brings us to a discussion about goals. The funny thing about high school kids is you’ll always get the vague “bigger, faster, stronger,” except in this case, many females choose “faster, stronger, and better abs” (cue the eye roll). The faster and stronger part we can measure, the better abs part may be translated as the following:

Coach: “Oh, you mean better shape? As in better condition.”

Player: “Yeah, that’s what I mean!”

That’s also not hard to measure. Or you can simply observe this as a “what the hell” effect, especially when employing 20s.

With all of my field athletes, I do an initial assessment involving a sprint, long jump, agility drill, and body dimensions. From a general standpoint, the numbers generated from this battery of tests seem to display the key interplay of strength, speed, and power for field athletes. In this case, it was particularly helpful with females who are typically self-conscience about getting “too muscular.” For both Meg and Kate, the absence of gaining body weight over this time period (127 lbs. and 142 lbs., respectively) had a two-fold positive effect. Functionally, as relative strength increased, these metrics improved. The density of their bodies allowed them to move more powerfully and efficiently. Perceptually, the young women were never hit by the scale demon and always fit into their clothes comfortably—if you’ve ever worked with high school females, you know how important this is.

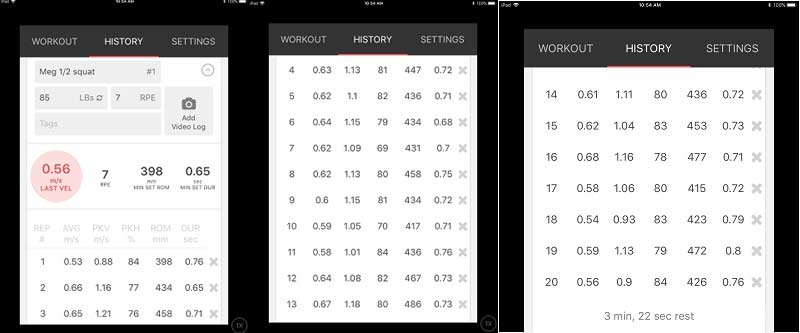

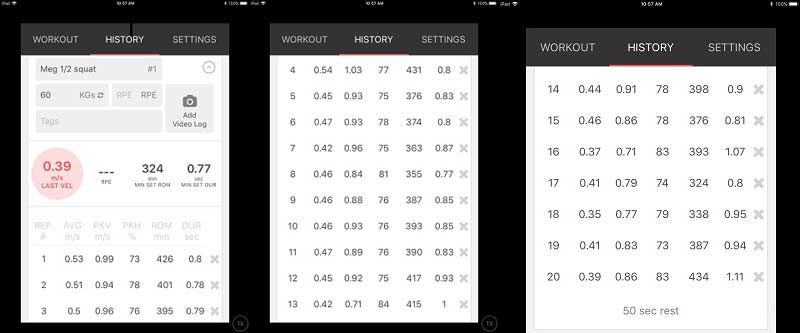

The following images show the velocities of each rep during the twenty-rep set. I was able to track Meg’s progress over several weeks because she began training with me before Kate. So goes life in the private sector—once one athlete sees results, she tells her friends and, soon enough, you get more athletes working with you. But I digress.

As to why this transpired, my guess is that it was her first session attempting a twenty-rep back squat, and she was feeling her way through the movement before fatiguing a bit at rep 10. Being the competitor she is and knowing she can’t quit on a 20, Meg hits nearly a 0.7 on reps 13 and 16 (see image above) before dropping back down in the 0.5s.

On her last rep, she jumps near 0.6 again, probably because she was cued to finish fast—intent is everything when you get fatigued! Upon close examination, you see some fluctuations as the speeds certainly did not drop uniformly as they would in a perfect spectrum. Again, I attribute the jagged outputs to her first endeavor into the 20s.

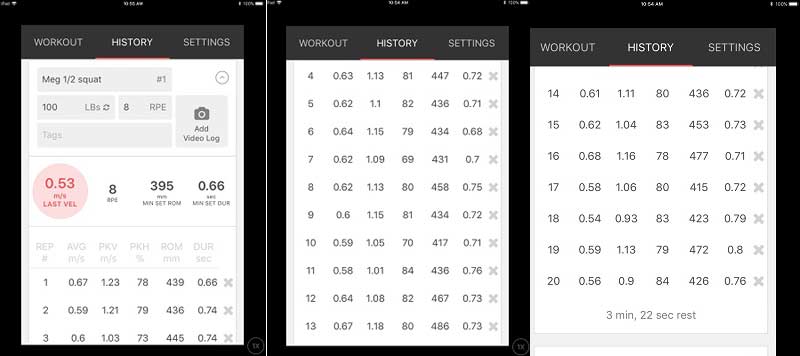

In the second and third pictures above, we see that Meg slowed down a bit to 0.53 m/s but maintained a fluctuation in the low accelerative range for the remainder of the set. In other words, she was able to repeatedly display her accelerative ability for 14 reps after the initial fast reps.

What’s more interesting is that she displayed faster bar speeds with an additional 15 lb.-load. This gives us insight into the type of strength she’s able to develop in the 1×20 system.

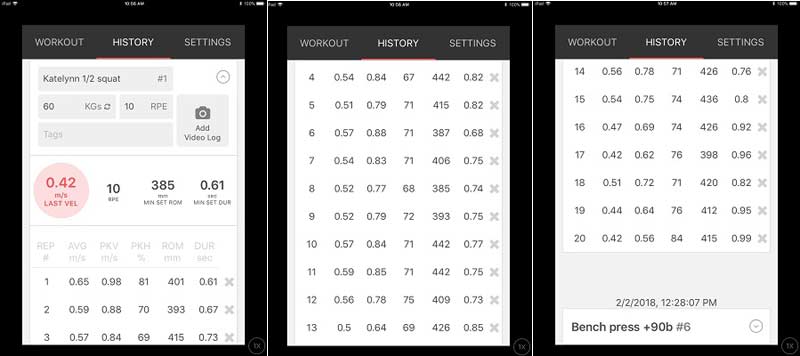

As you can see in the sequence above, Kate begins really strong at 0.65 before dropping a bit into the low accelerative end in the mid-0.50s in rep 4. From rep 5, she maintains speeds in the low accelerative range until rep 16, when she begins to teeter in the absolute strength zone to 0.47 and near-uniform drop until the last rep at 0.42 m/s. We can attribute Kate’s finish in the low 0.40 range to a few factors. First, she is a taller athlete—about 5’10” vs. Meg’s 5’5″ so has further to work. Second, I believe this represented an optimal load where Kate finished in a range that was closer to the absolute strength zone after fatiguing in the accelerative zone for about 15 reps, revealing the spectrum effect of the 20s.

In retrospect, using velocity based training (VBT) to manage loads and cut-off points instead of “failure” may help coaches keep rep quality in perspective, avoiding potential injuries. Twenties can be a tricky demon where athletes will find a way to compete to get their reps. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing unless they’re tumbling under loads or slopping it up with spinal posture. Here, using a bar speed cut-off can sharpen the coach’s eye while providing visual feedback so the athletes can’t argue that they had more reps. Knowing each athlete’s cut-off speed will help coaches determine optimal loads.

Knowing each athlete's cut-off speed will help coaches determine optimal loads. #VBT #1x120System Share on XAbout six weeks after her initial session with 85 lbs., Meg increased her squat to 132 lbs. (we jumped ten pounds every time she got to 20). As mentioned above, she did not put on one pound of bodyweight in the six weeks. **This will come into play in a follow-up article as I show how this transferred to her speed and agility markers.

In the sequence above, Meg maintains that force production capability until rep 15, where the “weight” of the load has become heavier in the 0.37 range. (In Dr. Mann’s recommendations, 0.30 m/s is the slowest cut-off for the squat lift [3; pg. 48]). Meg then maintains the high-end absolute strength zone for the 5 remaining reps.

Key Takeaways

Many contend that everything we do in the weight room or in our programming should complement and amplify an athlete’s skill—an outlook I share, particularly within the landscape I operate in of over-played, over-competed high school athletes. For Meg and Kate, this endeavor with the 1×20 system allowed us to stay safe while pushing up general strength and work capacity in an efficient manner. Given that training sessions will become few and far between with the pending season, this program helped lay the groundwork for the myriad of qualities needed during their season.

Using velocity based training with the 1x20 system allowed us to stay safe while pushing up general strength and work capacity efficiently. Share on XThe progress from this system also allowed us to leave a little on the table, given the low neural cost and the conglomerate of other qualities trained along the way. This will come into play as they progress to the collegiate level, where the work becomes more intensive as the stakes become higher. Also, the technical skills Meg and Kate learned in the weight room will prove invaluable as they’ll be expected to hold their own when they enter fall camp.

These days, collegiate strength coaches are on to the fact that most incoming freshmen they train will have relatively low, or no, training age. It’s always good to know my kids can get in there and know the “language,” the technique, the program, and the retention and response of the trainable qualities.

For me, as a coach, this experience spawned a couple of revelations:

- I can certainly use a VBT device in the training of lower level sportsman. My old thinking was that athletes had to “qualify” to use it (meaning they had to be in a position where we would employ the dynamic effort method). If you work with developmental clientele, you’ll find this a rarity as a reserve of strength and consistent technique are a must.

- The readings from the device serve as a calibrator of sorts, both for athlete and coach. If the urgency of doing a single set is not enough (no do-overs in my room!), the proof is in the numbers. For the more aggressive athletes who want to load at any cost, the numbers will tell us when to stop. For the complacent athletes who don’t (or simply will not) load the bar despite hitting the rep mark, we can keep it and show improvement or regression in the speeds. In either case, the intent is everything.

If you’re a coach battling with if and how the 1×20 can work, I hope this article answered some of those questions. In the follow-up to this post, I’ll present other metrics that grew congruently with this system. Even if you don’t have a VBT device, a keen coach’s eye, along with measuring things like jumps, sprints, and agility drills, may allow you a similar “scope on the rifle” that VBT offers with this system.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Moyer, Jeff. “A Minimalist Approach to Building a Better Athlete.” Track and Football Consortium VI, December 2017.

2. Mann, Bryan. “Bryan Mann Talks Velocity Based Training.” elitefts (website), April 2, 2015.

3. Mann, Bryan J. Developing Explosive Athletes: Use of Velocity Based Training in Athletes. Ultimate Athlete Concepts 2016.