Speed kills. Sprint training will enhance body composition, build explosive power, and increase an athlete’s ability to make a game-defining impact on their game. I designed The Blue Program to introduce sprint newbies to speed development without blowing a hamstring in week one, so athletes can make long-term gains and become more effective all season long.

Research consistently demonstrates that faster athletes make more big-time plays1, appear better conditioned, and even make more money2. There is no denying that to be the best, your athletes must address sprint speed. Some will argue it’s all genetic, but my experience working with various athletes at all levels has shown me that speed is a trainable quality. And while I can’t turn the weekend warrior into Usain Bolt, everyone can get faster and improve their ability to make a bigger impact on game day.

Intricate technical drills and confusion regarding efficiency and effectiveness of body positions and postures leaves many athletes intimidated and unsure of how and where to begin. Share on XBecause the importance and trainability of speed is becoming more well known, I have noticed an increasing number of questions from parents, coaches, and athletes coming my way. They know they need to be sprinting, but intricate technical drills and confusion regarding efficiency and effectiveness of body positions and postures leaves many intimidated and unsure of how and where to begin. That’s why I created The Blue Program for building game-breaking speed.

Foundations

This program is an amalgamation of the various speed development programs I’ve rolled out with basketball, rugby, soccer, and cricket athletes over the last five years and mostly closely resembles how I prepare my academy Cricket New South Wales athletes today. I designed this program to establish a foundation of general physical preparation for team sport athletes who want to begin regularly sprinting, and it sets the scene for more individualized approaches with technical coaches down the line. This program is most appropriate for uninjured, active athletes 16 years of age and above, but you can also use it following a return to running program for reconditioning from injury.

Before we get into the program, let’s establish a few key things:

- Technique is critical.

- To begin with, focus on a tall, proud, and relaxed posture when sprinting.

- Work the hands from the lip, back past the hip, and let the elbow flex and extend between the front and backswing. Arms should be smooth and relaxed, not robotic or mechanical. Drive the arm action at the shoulder.

- Initiate the foot strike through the ball of the foot and aim directly beneath the hip—do not “run on your toes.”

- Use a front-side dominant lower limb action—get the legs working in front of the body as much as possible by driving the knee high. Avoid a big, long kick out the back after toe-off.

- Fatigue is the enemy.

- A proper speed development program requires plenty of intra-set and inter-rep recovery. For some, this may feel like dead time. But as the legendary sprint coach Charlie Francis famously taught, anything under 95% of top speed is just conditioning. If we fatigue as the workout progresses, our outputs will diminish, and before long we’ll have stopped making progress with the goal in mind. While this program isn’t always about max effort sprinting, when longer rests are prescribed, it is critical they are adhered to.

- Sprint training is a risky business.

- For team sport athletes who have never followed a speed training program, this is the program with the greatest injury risk they’ll ever complete. Running at top speed exposes muscles and tendons to movement velocities that can never be replicated in the gym. This is why this program is so important to follow before going headlong into a full-blooded speed development program.

- This program aims to build tissue tolerance and condition the body to handle top speeds, so that once completed, the athlete can push the limits and get maximal gains. Follow The Blue Program to the letter before individualizing programs later down the line.

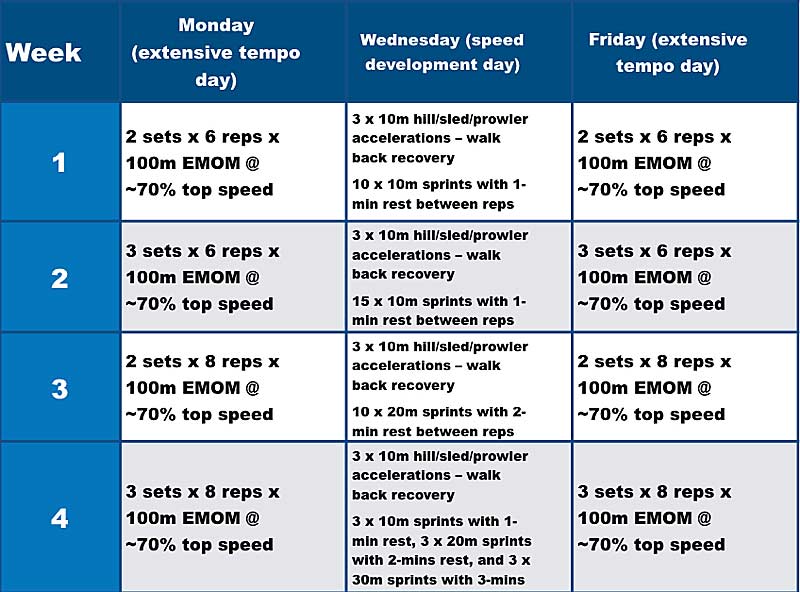

The program consists of two main blocks. Block one is an accumulation phase, with two extensive tempo sessions each week and one speed development day. In the second block, an intensification phase commences, and the script is flipped to one extensive tempo day and two speed development sessions each week. I designed this program to be completed in the off-season; however, by eliminating one set from each tempo session and halving the reps on speed development days, athletes who just can’t wait to get started can also safely and effectively complete it during the pre-season or in-season.

Warm-Up

Because sprinting exposes the body, particularly the feet, calves, quads, and hamstrings, to such large magnitudes and rates of force, a proper warm-up is critical. The warm-up for this program consists of two components. Component one is the general dynamic warm-up and component two is the sprint-specific priming and potentiation exercises.

Because sprinting exposes the body, particularly the feet, calves, quads, and hamstrings, to such large magnitudes and rates of force, a proper warm-up is critical, says @nathankiely_. Share on XGeneral dynamic warm-up—perform each for 10 meters walking.

- Hamstring ground sweeps

- Lunge with overhead reach

- Toe walks

- Arabesque

- Quad stretch

- High kicks with a straight leg

Video 1. I have carefully selected these bang-for-your-buck exercises to increase range of motion and also strengthen and activate specific muscle sites of common injury seen in high-speed running.

Sprint-specific priming and potentiation.

- Dribble build-up: 2 x 30m with walk back recovery

- Fast feet with knee drive, actively dorsiflex the ankle at all times, focus on landing on the ball of the foot.

- Perform first 10m small cycles, middle 10m medium cycles, and final 10m big cycles with intent to snap up and into the glute with the heel.

- Triple exchange: 2 x 10m with walk back recovery

- 1-2-3 stick and hold.

- Emphasize vertical displacement—this should feel bouncy up and down, not rushed like you’re tripping over yourself while moving forward.

- A-skip with switch in the air: 2 x 10m with walk back recovery

- 1-2 jump and switch.

- Focus on limb exchange during flight phase.

- Straight-leg scissor bound build-up: 2 x 30m with walk back recovery

- Keep knee extended at all times by flexing quad; initiate ground contacts by pulling back and down through the glute and hamstring.

- Perform first 10m short strides, middle 10m medium strides, and final 10m long powerful strides with intent to cover as much ground as possible with each stride.

- Stride-throughs with walk back recovery

- 1 x 10m @ 75%

- 1 x 20m @ 85%

- 1 x 30m @ 95%

Rest for three minutes following the warm-up prior to commencing the day’s training session.

Video 2. The four exercises in this video target ankle stiffness, hip lock, extension reflex, and posterior chain-driven paw-back to facilitate improved self-organization and performance while mitigating injury risk. Take your time to explain, demonstrate, and provide feedback to athletes on their technique in these exercises, as they can take some time to learn.

Phase One – Accumulation

The accumulation phase, as the name implies, is all about building work capacity. Each week progresses in volume and intensity to create a broader base of high-speed running conditioning. These volumes and intensities are initially inspired by guidelines and programs from great coaches like Keir Wenham-Flatt, Graeme Morris, and Mike Young. However, I have modified these to complement all elements and the context of this specific program.

You should use hills, sleds, or prowler sprints immediately prior to completing the main exercise on each speed development session to provide a neuromuscular priming effect and reinforce effective and efficient application of ground reaction forces. A hill of an approximately 20- to 30-degree incline is usually best, but other hill inclines can work just as well. If you’ve got access to a sled or prowler, this can be an even more effective tool for overloading specific acceleration qualities.

For sled or prowler sprints, based on research by Cross et al.3, a load of 75% of body weight should be used for resistance to optimize peak power output. Some coaches believe this is far too heavy, as it changes technique; however, contemporary research shows lighter sleds may not be as effective as first thought4 and that sled loads up to 130% of body weight can be highly effective for improving sprint performance5.

Video 3. Athletes can perform resisted sprints up a hill, using a prowler, or with a sled like the SKLZ SpeedSac.

The extensive tempo sessions are used to build tissue robustness and improve conditioning to handle repeated exposures to high contractile velocities. Each of these tempo sessions is a simple every minute on the minute (EMOM) workout. This is where the athlete keeps a rolling clock and commences each new repetition as the clock ticks over the minute.

In this type of training, the recovery time is dictated by the speed at which the work is completed. For example, if the athlete completes their 100m in 18 seconds, they get the remaining 42 seconds in the minute as their rest period. Take a full three minutes to rejuvenate between sets in the tempo sessions.

A heart rate monitor may be useful when completing extensive tempo training. The goal is to avoid excessive lactate and glycolytic metabolite accumulation by staying in a predominantly aerobic state. To do this, a helpful guide is to keep the heart rate below 80% of maximum at all times (estimated HR max = 220 – age in years). If the athlete’s heart rate climbs progressively throughout the set, you should decrease velocity to allow for the retention of an aerobic state.

A typical male high school athlete should start by aiming to complete all tempo 100s in under 20 seconds. A well-trained adult male team sport athlete should aim to complete tempo 100s in 16-17 seconds. The tempo session should feel easy, and they should execute the last repetition with the same level of rhythm, relaxation, and technique as the first—err on the side of too slow if you’re unsure. Remember, in speed development, lactate is the enemy—avoid it at all costs.

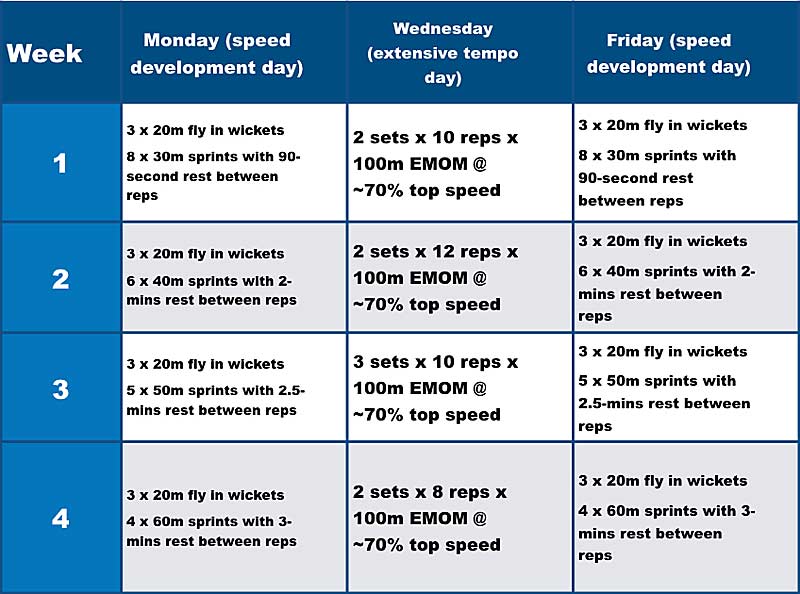

Phase Two – Intensification

The intensification block changes tack from phase one and begins to emphasize exposure to high-speed running, leaning heavily on inspiration from Mike Young’s speed development guidelines for team sport athletes. Two entry criteria must be met before commencing phase two: the athlete is injury-free and there is no excessive overreaching (consider regular assessments of neuromuscular fatigue via jump testing). This phase uses intensity to drive adaptation and development—while plateauing the volume of work capacity sessions—so recover just as hard as you train during this block.

Phase two begins to emphasize maximal velocity sprinting, and the mini-hurdle wickets drill is an especially useful exercise for improving this aspect of technique. Use wicket runs to practice a strong knee drive, maximal hip height, and vertically orientated foot strikes immediately prior to all-out sprinting on the speed development days. During phase two, tempo 100s should be completed around one second faster than they were in phase one.

Video 4. In this clip I explain the purpose, benefits, and application of the mini-hurdle wicket drills, as well as the correct spacing and setup for seamless delivery in your training sessions.

Once athletes complete this eight-week program, you can bet your bottom dollar they will be better conditioned, have improved body composition, be faster and more explosive on the field, court, or pitch, and be ready to make game-breaking plays week in and week out.

A Word on Strength Training

Yes, you can and should be completing strength training at the same time as this program. Many roads lead to Rome when it comes to getting strong, and I’m not about to tell you which of the many great programs you must follow in conjunction with The Blue Program—besides, that’s outside the scope of this article. However, you should make a few key considerations to optimize training adaptations and mitigate injury risk.

You should prescribe heavy lower-body strength training—particularly targeting the posterior chain—with care. Consider prescribing lifting after sprint training on the same day. This may compromise your outputs in the weight room, but no one ever won a match with a game-defining deadlift, so just suck it up.

This will allow for improved recovery—do not train lower body on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Sundays (the day before Blue Program sessions)—and create greater windows for adaptation. I also recommend incorporating exercises specifically designed to address sites and mechanisms responsible for injury during sprinting, such as Alex Natera’s run-specific isometrics, Nordic hamstring curls, and unilateral strength movements such as split squats and step-ups.

Be Ambitious

Most speed programs I’ve read on the internet aim too low, treating athletes and coaches as if they cannot handle complexity, or they use sprinting as a general training tool for the average Joe. This means they fail to adequately consider the nuance of physical preparation in athletic populations—promising all the rewards, but conveniently ignoring the risks. That’s why I felt The Blue Program was so dearly needed: A program aimed at smart coaches and athletes who want a starting point for getting fast without blowing a hamstring two weeks in.

Most speed programs I’ve read on the internet aim too low, treating athletes and coaches as if they cannot handle complexity, says @nathankiely_. Share on XI’ve used similar periodization and progression in my speed programs over the last five years and consistently see improved sprint times, greater impact on game-defining plays, and greater levels of robustness and injury resilience. This program is the synthesis of my learning, practice, mistakes, and coaching triumphs during this time period.

A strength coach once told me: “Getting strong is easy. It’s like falling out of a boat and hitting water—anyone can do it.” Speed development, on the other hand, is a tough task and takes years of refined coaching and work to build. Speed grows like a tree from a seedling, slowly gaining height over the years. But with The Blue Program, there’s no longer an excuse not to start the quest for getting fast. By following The Blue Program, you plant the seeds today that can be reaped tomorrow.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Faude, O., Koch, T., and Meyer, T. “Straight sprinting is the most frequent action in goal situations in professional football.” Journal of Sports Sciences. 2012;30(7):625-631.

2. Treme, J. and Allen, S.K. “Widely received: Payoffs to player attributes in the NFL.” Economics Bulletin. 2009;29(3):1631-1643.

3. Cross, M.R., Brughelli, M., Samozino, P., Brown, S.R., and Morin, J.-B. “Optimal loading for maximizing power during sled-resisted sprinting.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 2017;12(8):1069-1077.

4. Clark, K.P., Stearne, D.J., Walts, C.T., and Miller, A.D. “The longitudinal effects of resisted sprint training using weighted sleds vs. weighted vests.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2010;24(12):3287-3295.

5. Cahill, M.J., Oliver, J.L., Cronin, J.B., Clark, K.P., Cross, M.R., and Lloyd, R.S. “Sled-push load-velocity profiling and implications for sprint training prescription in young athletes.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2019.