[mashshare]

How do you really know that the program you have written is the cause of your athletes’ positive adaptations? How do you know they aren’t just achieving success in spite of your program, due to their natural ability and genetics? As a coach, it is a tough question to answer, not only because of the complexity of understanding the human body as an ever-changing organism, but also because it forces us to acknowledge that we might not have as large of an influence on our athletes as we initially thought.

The challenge for all coaches is to truly discover what are an athlete’s drivers of adaptation. We must seek and problem solve to determine the key stimuli that make this athlete better, and then begin to direct more of our training program toward this.

The challenge for all coaches is to truly discover an athlete’s driver of adaptation, says @dylhicks. Share on XAcross the 2017–2018 season, I was coaching a group of mainly short and long sprint athletes. During this season (including a few months prior to the season starting), I was working with a young sprinter who went from being a solid club-level athlete to running the third leg on the 4x100m at the 2018 World Junior Championships in Tampere, Finland. It was a good achievement for both of us to get to this point; however, I think this stage is where many coaches can get it wrong.

Upon further reflection, this achievement had little to do with the program that I wrote. Yes, he came into a group with more structure and specificity, and some senior athletes to work with and learn from, but the athlete had a better-than-average level of natural talent and, along with hard work and consistency, the performances were brought out. The drivers of adaptation were specificity and determination.

But this information does not guide future training programs or provide insight into what type of training the athlete best responds to. I’m not underestimating my role in the process, but I believe many coaches could have achieved the same given the circumstances. In instances like this, it is likely still unclear what the true driver of adaptation is—assuming they are healthy, most young athletes will continue to improve on a simple diet of specificity.

But once the athlete moves into the senior ranks and the “teenage testosterone” boost no longer provides PR’s every time they hit the track…then what? What are you going to do to improve your athletes at this stage?

Much of this blog post consists of my initial thoughts on a podcast from HMMR Media with Stu McMillan of ALTIS, where he discussed (and I’m paraphrasing) how to progress the program (and athlete) once the training principle of intensity is exhausted. As with the example above, with young athletes, specificity and intensity are the major drivers of adaptation. As a coach, this is the easiest programming you will ever do. You could go on autopilot for several seasons using the same program and tweak these principles, and the PR’s will keep coming. Everyone will think you’re a genius. Often, other athletes see this progress and want to join the training group, without critically analyzing what is driving adaptation.

I have not been coaching anywhere near as long as Stu, but I have coached athletes at both the start and toward the end of their respective careers and know that thinking the same stimulus will drive adaptation is crazy (something he also referred to in that discussion). It’s like comparing an old car whose odometer has circled back around to a new car that is being driven out of the dealership. In my opinion, true coaching begins here.

I’ll be the first to admit, I have messed this part up. I failed to study my individual athletes and discover what was driving their adaptation(s). For some that I coached, they either didn’t adapt or they got worse, and at the time I didn’t recognize why. Not acknowledging this would be ignorance on my part.

Understanding Adaptation

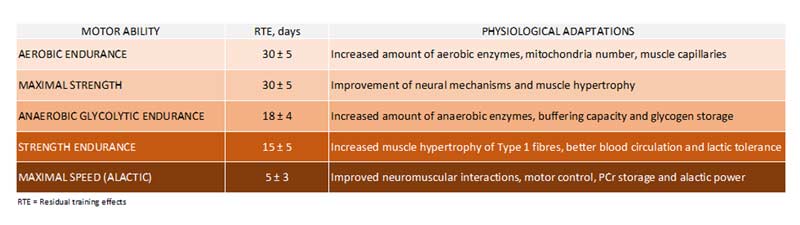

The first thing coaches need to be aware of is the length of time it takes for adaptations to occur. Some coaches know this information anecdotally, while others defer to the science. I don’t believe it really matters, but you need to know the rough timeframe of how many exposures (sessions, weeks, months) to the stimuli will provide the adaptation you desire, along with the residual training effect of how long the adaptations will remain if you do not train them frequently1 (figure 1). For example, anaerobic, aerobic, and alactic adaptations all occur and dissipate at different rates and, therefore, must be trained accordingly.

Too often, coaches change the theme (or priority) of the program before the adaptation occurs, says @dylhicks. Share on XOne area I think coaches can improve in is providing greater training time throughout the cycles to allow the adaptation to occur. Depending on the nature of the training focus or theme, adaptations occur over weeks to months and you cannot rush them. It takes as long as it takes. Too often, coaches change the theme (or priority) of the program before the adaptation occurs, usually because the month ended, the cycle concluded, or they want to try the “flavor of the month” training session.

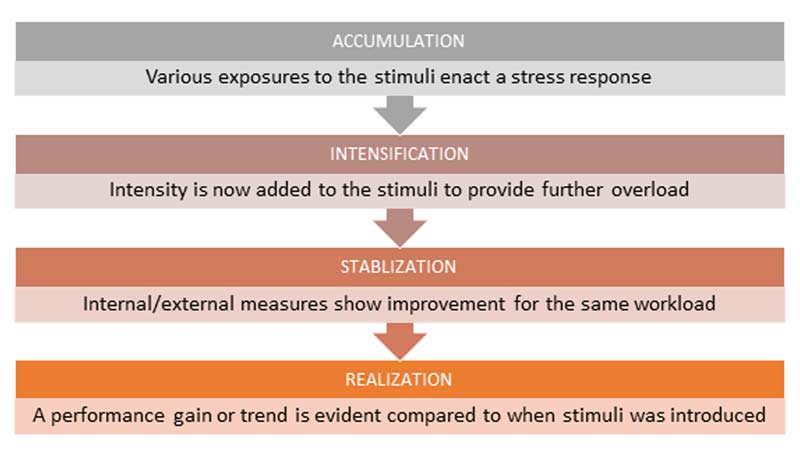

The process of introducing the stimulus and stress; allowing time for motor learning, skill acquisition, and responding to the stress; and then stabilizing and adapting to the stress is important to understand for training design. Vladimir Issurin’s work in regard to block periodization—where he describes the training process and how adaptations occur across mesocycles—can be a useful starting point with its introduction of the following terms: accumulation, transmutation, and realization.1

Although these concepts are not the sole focus of this article, the classification across cycles can be varied to understand training design. One variation of Issurin’s original work, and one which I think is effective for understanding the concept of adaptation along with training design, is detailed in figure 2. The visual is not specifically a reference to block periodization, but it provides a thought process of how coaches could think about applying stress to the system. Sometimes I think coaches write the sessions without truly thinking about what adaptations they want the session(s) to elicit.

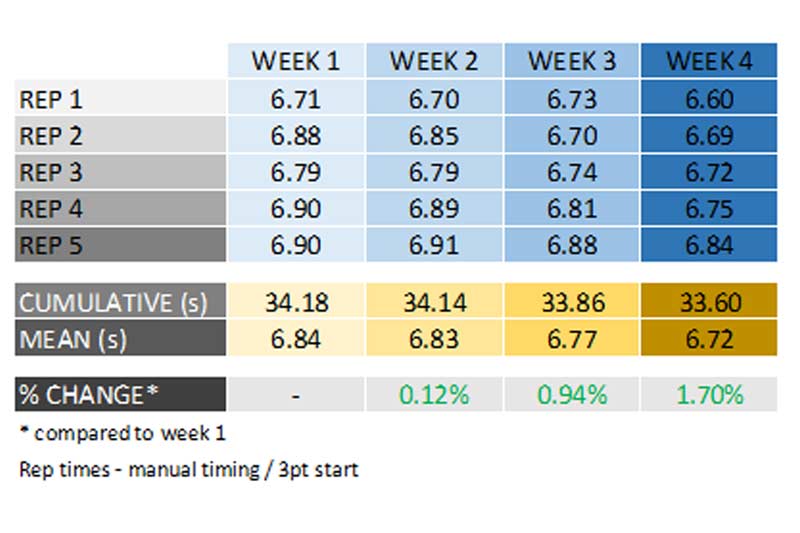

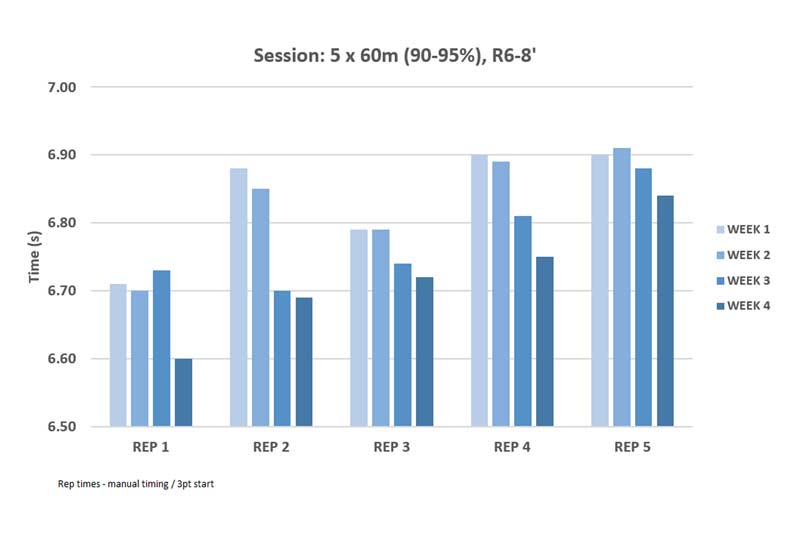

To determine adaptation (stabilization and realization) for my sprint group, a common session I used during the SPP involved running 5 x 60m reps at approximately 90–95% (not all-out), with 6–8 minutes’ rest between reps (figures 3 and 4). Over time, I wanted the athletes to demonstrate quality across all reps (specific work capacity), rather than having two strong performances and then dropping off for the final three. The session demands the athlete to put together a strong drive phase and transition to maximal velocity, but also show good speed endurance qualities across the series of runs (30–45 minutes), perhaps simulating multiple warm-ups and races in a day (albeit quite concentrated).

You can see the cumulative and mean time diminish across the weeks, which corresponds with a 1.7% performance change across four weeks. This is significant across a 60-meter distance and demonstrates a positive response to the stimulus. Having too much range in the rep times (one fast time, some in the middle, final rep significantly slower) probably wouldn’t demonstrate adaptation to this session and would require greater analysis of why this athlete has not responded to the imposed demands.

Anecdotally, I think coaches introduce a new stressor before the athlete has even responded/reacted, let alone stabilized against the previous stressor. Be boring and keep repeating the same series of sessions until you can see the athlete has adapted. How you do this is up to you—voila, the art of coaching!

Using the athlete mentioned above as an example, during that season I made a priority to streamline the training process and focus on three themes all season, with acceleration as the priority (micro-dosed each session) and—for the majority of the time—little variation in structure. Our focus was:

- Tuesday: acceleration

- Thursday: maximal velocity

- Saturday: speed endurance

Rocket science, I know! But I was just trying to control the variables by keeping the training pattern the same to observe when things were changing (for the good or the bad). Many coaches add too much to the recipe, leaving them unable to identify what is causing the change. You can’t determine which sessions or structure of sessions are driving adaptations if you keep changing the type of variable, or if you change them too frequently.

You can’t determine which sessions or structure of sessions drive adaptations if you keep changing the type of variable, or if you change them too frequently, says @dylhicks. Share on X

Responders vs. Non-Responders

From a medical viewpoint, it would be beneficial to understand why some patients respond favorably to a certain cancer treatment or intervention while other patients do not. This would create a discussion of responders vs. non-responders. Why did group A respond positively to the cancer drug, but group B showed no changes? The same can be said for coaching interventions. Why do some athletes adapt, respond, and improve, while other athletes stagnate?

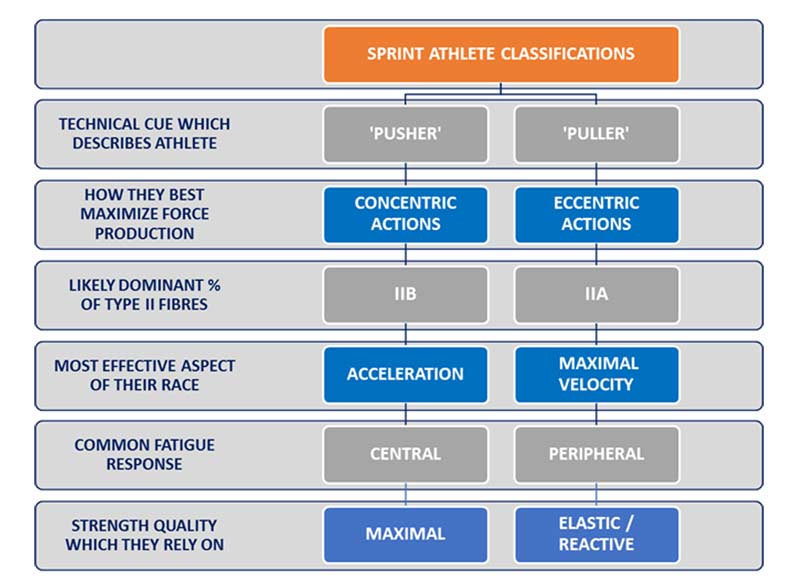

Again, this is multifactorial, but the quicker we, as coaches, try to understand why, the better. In regard to sprinters, I’ve seen various means to classify athlete types in the hope that the classification assists training direction and, ultimately, performance. Sprint athlete classification types (figure 5) have included athletes who are focusing on pushing or pulling, show a central or peripheral fatigue response, or those we think have a dominant percentage of type IIA or IIB muscle fibers.

Most of these classifications are a guess, relatively ambiguous, and subjective; however, they serve the purpose of discovering where the bulk of the training program should be directed. If coaches can match up the classification type with their training program, we may end up with more positive athlete response(s) compared to non-responders. One thing that can become a roadblock in this situation is the coach’s training philosophy or system. Assuming the coach discovers what drives adaptation to the athlete system, if they refuse to compromise on their training system, then improvement is ultimately limited.

Using Testing to Classify Athletes

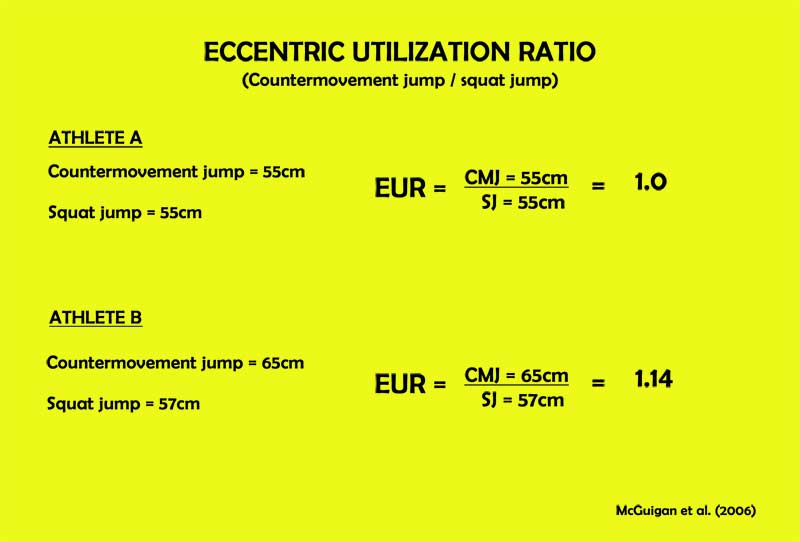

When classifying athletes, all we are doing is making large-scale assumptions about which “bucket” we can place them in. We make our best guess, but it must still be a fluid process between buckets if necessary. Two simple tests (and a ratio) you can use to classify sprint athletes are the squat jump (SJ) and countermovement jump (CMJ), and the eccentric utilization ratio (EUR).

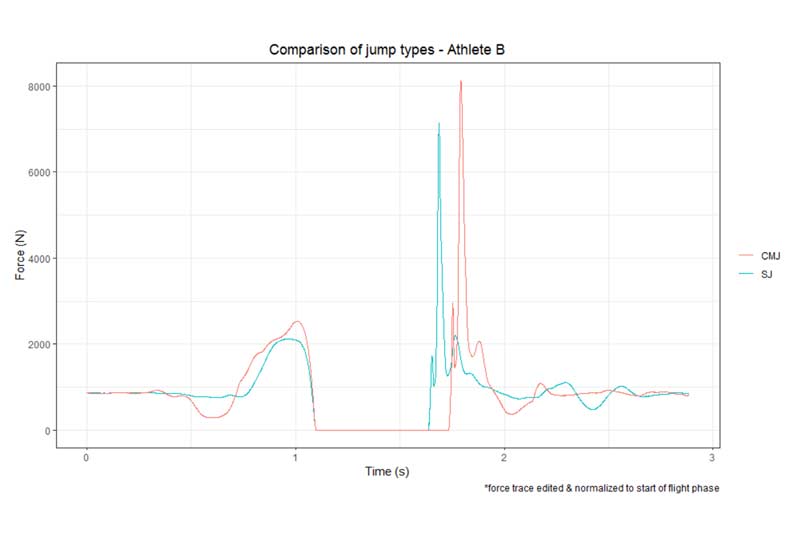

Jump tests are easy to administer and require limited equipment, and performance (jump height/maximal power) is often a strong indicator of overall athleticism. Squat jumps are commonly used to measure concentric strength (starting strength), whereas the countermovement jump is a measure of reactive strength of the lower body2. To determine jump height and maximal power, you can access a force plate (figure 6).

I recently purchased two PASCO force plates, which are reasonably affordable (albeit not as robust as Kistler plates, etc.) If you don’t have access to this technology, you can purchase the MyJump2 app for less than $15 to determine jump height and maximal power (plus other variables). Once these values are known, you can calculate the EUR by dividing the CMJ value (cm or watts/kg) by the SJ value (cm or watts/kg) for either height or power (figure 7).

Assuming there are no coordinative issues regarding jump technique, when comparing these two athletes, you could uncontroversially assume that Athlete A relies more on their mechanical (concentric) ability to transmit force than their ability to use the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) and elastic/reactive strength. Using very broad stereotypes, Athlete A may be strong through acceleration; however, they lack the ability to keep “bouncing” once they’re into the maximal velocity and maintenance/deceleration phase. This athlete may be a typical 60m/100m type.

Athlete B shows a EUR that suggests they have a strong level of elastic strength and can use their SSC/connective tissue effectively. Again using stereotypes, this athlete may still be quite good during acceleration, but may in comparison excel to a greater degree while at maximal velocity, maintaining their “bounce” and being the more typical 100/200m athlete. This is where they can show strong speed endurance qualities and often run past other athletes in the closing stages of both sprint events.

This is just one example of using testing to classify athletes. You could use many field-based (or track) tests to determine current status and the strengths and weaknesses of the athlete.

Training Systems

Another thing McMillan discussed in the aforementioned podcast was how some athletes change training groups and then adapt (or respond) positively to the new training system, going on to perform well. Others, however, do not. As he mentioned—and I wholeheartedly agree—there are numerous reasons this could be the case. It is easy to throw stones from the sofa while watching an athlete underperform at the elite level, without ever knowing the context.

When athletes change training groups but don’t perform to the same level (assuming they are healthy), I strongly believe the coach hasn’t discovered what drives the system. Share on XSeeing the same situation at a lower level in my own context, when athletes change groups and don’t perform to the same level, assuming they are healthy, I strongly believe the coach hasn’t discovered what drives the system (and I’ve made this mistake too). Often, this is because the athlete has not been there long enough, and the sample size of sessions is too small. It’s a tough spot to be in. Track and field is a results-driven business. No one wants to hear excuses.

If the training system they have come into goes against what drives adaptation, some hard decisions need to be made by both the athlete and the coach. For example, if intensity has always been the focus of the previous training system, and the athlete moves to a training group where this is not the major focus, you will initially have problems. The stimulus the new system provides will likely not exceed the adaptation threshold, and so improvement will likely halt. The coach now needs to get creative.

Adapting to the System

Magical things happen when you find that athlete who instantly responds to the program you are writing. And, as all good coaches do, you keep feeding the beast with this type of training, and the athlete keeps improving until they have adapted to the stimulus. At this point, most coaches would revert to manipulating typical training principles (e.g., volume, intensity, frequency, density, etc.). However, it is still the same system and philosophy. Once athletes (usually senior athletes) have adapted, you reach the point of diminishing returns: You cannot keep giving them more of the same type of training and expect it to provide a new stimulus and higher performance level.

I believe this is where the undervalued training principle of variation could be appropriately utilized. While still appreciating the athlete classification and the driver of adaptation, I’d challenge coaches to experiment with using an alternate system with these athletes—still specific to the overall goal (such as sprinting), but with enough variation in the programming to elicit a new stress response. After all, that’s all we, as coaches, are trying to do for our athletes.

- Stress their system.

- Allow time to adapt.

- Watch them perform.

I don’t believe variation of the same training system is the same as changing the programming mindset to elicit a new stress. This is where elite coaches show their true colors. Yes, it is an experiment, but all coaching is. Not recognizing athlete stagnation is a coaching error. You need to have a regular, systems-based approach to determine when they are no longer adapting to what you are writing. It is not up to the athlete to determine this, yet they will likely voice some opinion if things are not going well once the season begins.

Not recognizing athlete stagnation is a coaching error. You need to have a regular, systems-based approach to determine when they are no longer adapting to what you are writing. Share on XAt a certain training age, it may be time to forget if it’s not broke, don’t fix it, and in some form break the athlete down. This process will look different in every case, but if you are looking to drive new adaptations, this may be just what the system needs.

Focus on the Adaptation’s Driver

Focusing on the drivers of adaptation is an important concept to understand in order to appropriately program for your athletes. To determine the driver(s) of adaptation, coaches should try some of the following:

- Use typical testing protocols or regular workouts to classify your athletes.

- Link classifications to what YOU think drives adaptations.

- Match up the classification of athlete with workouts that are directed to their driver.

- Incorporate regular structures into training cycles to determine rate of adaptation (internal/external, subjective/objective monitoring).

- Assuming they are healthy, if athletes are not responding to the workouts, assess whether they have already adapted to the stimulus, it’s the incorrect stimulus for them, or the training system must be varied due to their training history.

All we are doing as coaches is experimenting with workouts and hoping they positively impact the athlete. The quicker we know what type of workouts will drive adaptation, the faster we will see improvements with our athletes.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

1. Issurin, V. “Block periodization versus traditional training theory: A review.” The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness.2008; 48(1): 65–75.

2. McGuigan, M., Doyle, T., Newton, M., Edwards, D., Nimphius, S. and Newton, R. “Eccentric utilization ratio: Effect of sport and phrase on training.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2006; 20(4): 992–995.