[mashshare]

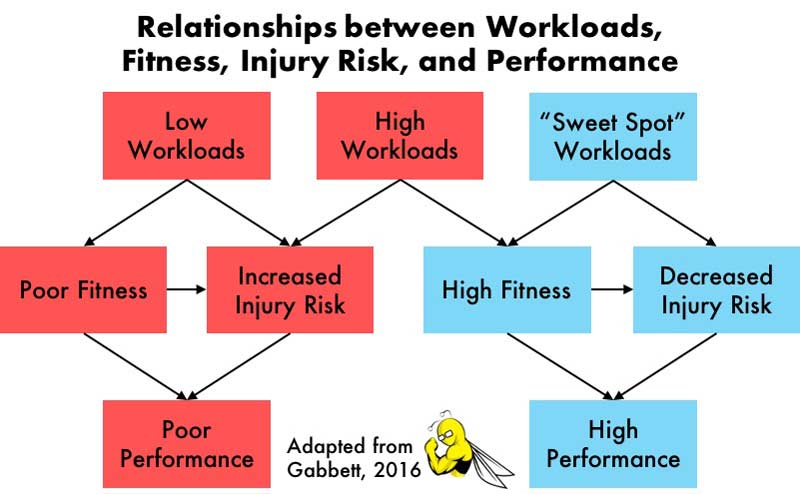

When training and rehabilitating athletes, the sports science professional has two crucial but apparently paradoxical responsibilities: He or she is simultaneously charged with minimizing risk of injury (or re-injury) and maximizing performance. However, to maximize performance, high workloads are required, and high workloads are often associated with increased injury rates.

Therein lies the “training–injury prevention paradox.”1 How can the practitioner help improve the athlete’s performance if the more the athlete trains, the more likely they are to sustain an injury? Is there a way to enhance performance without increasing injury risk? To solve this paradox, Australian applied sports scientist Tim Gabbett recently developed the Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio Model.1

Types of Workloads

Before delving into the model, an understanding of workloads is essential. In general, a workload is any training or competition stimulus an athlete undergoes. There are two different types of workloads: external and internal.2 External workloads correspond to the amount of work an athlete performs (e.g., distance, speed, duration, or total pitches thrown). Internal workloads denote the athlete’s physiological or psychological response to an imposed external workload (e.g., blood lactate, heart rate, or rating of perceived exertion).

Because different athletes respond to the same external workload with different internal workloads, both types provide useful data.3 Often, internal and external workloads are multiplied to create a “combination workload.” The most common combination workload has been termed “exertional minutes” and is the product of training duration and session rating of perceived exertion.1 For example, suppose an athlete’s rating of perceived exertion for a 90-minute training session is 8 out of 10. This would correspond to a workload of 720 arbitrary units.

Effects of Workloads on Injury Risk and Performance

When an athlete takes on a workload in training or competition, two performance-altering processes occur: fitness and fatigue.4,5 Naturally, fitness enhances the athlete’s performance. In conjunction, the athlete develops physical qualities that protect against injury (e.g., strength, power, and repeated-sprint ability).6,7 Furthermore, the more injury-free the athlete remains, the better they perform.

Conversely, Dr. Gabbett explains that fatigue causes the athlete’s performance to suffer.1 Fatigue also subjects the athlete to increased injury risk, which would further impair performance. The nature of the workload determines the degree to which fitness or fatigue dominates the athlete’s response to the imposed workload.1

The nature of the workload determines whether fitness or fatigue dominates the athlete’s response, says @trpollen. Share on XFor example, high workloads lead to high fitness, but they can also lead to high fatigue and, consequently, increased injury incidence. This relationship is well-documented across a variety of sports (e.g., rugby, Australian football, and baseball), levels of play (e.g., youth, sub-elite, and professional), and workload types (e.g., external, internal, and combination).8-14 The studies have consistently shown that as all types of workloads increase, injury incidence also increases. Moreover, reducing training duration and intensity tends to reduce injury rates.9

Based on this research, the simple solution to the injury problem would seem to be a sweeping reduction in workloads. In fact, in an effort to reduce injuries, some sports medicine practitioners do lobby for reduced workloads.15 However, reducing workloads may actually have the contradictory consequence of hampering the fitness response, a necessary component for injury reduction as well as performance.1

The 10% Rule

According to Dr. Gabbett, the problem with high workloads lies not in the absolute workloads themselves, but rather in an athlete’s relative preparedness for them.1 From this perspective, the so-called “10% rule” is another proposed solution to the training-injury prevention paradox. The rule states that an athlete should not increase their week-to-week workloads by more than 10%.16,17

The issue with high workloads is not a workload itself, but the athlete’s relative #readiness for it, says @trpollen. Share on XThe 10% rule is most commonly applied to running, but prospective data on rugby players and Australian footballers also supports the recommendation.1,18 For example, a 15% or more increase in weekly workload put ruggers at upwards of a two to five times increased likelihood of injury compared to a 10% or lower increase.1 Nonetheless, despite this prospective data, in a large-scale randomized controlled trial of 486 runners, there was no difference in injury incidence between those following the 10% rule and a standard training program.16

The Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio

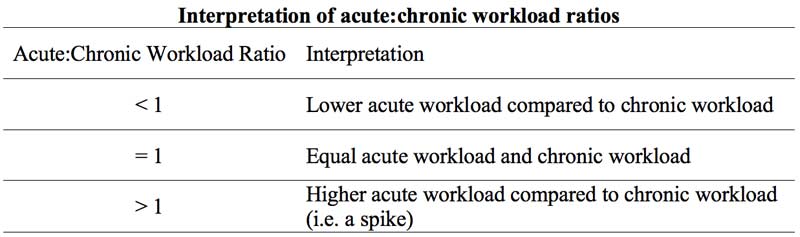

While the 10% rule may be a field-expedient heuristic in some cases, Dr. Gabbett’s Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio Model endeavors to characterize athletes’ preparedness more completely. Dr. Gabbett asserts that an athlete’s preparedness is dictated by their chronic workload.1 Chronic workload is the workload an athlete is accustomed to on a medium-term basis. It’s typically calculated as a rolling average of the preceding four weeks. This time frame may be more indicative of the athlete’s current level of fitness than the previous week alone (as with the 10% rule).

The acute:chronic workload ratio may be the best solution to the training-injury prevention paradox, says @trpollen. Share on XMeanwhile, the acute workload is that which the athlete faces presently, typically over the most recent week. The quotient of the acute and chronic workloads represents the acute:chronic workload ratio. Values of the acute:chronic workload ratio much larger than 1.0 can be interpreted as workload “spikes.”

The acute:chronic workload ratio may represent the ultimate solution to the training–injury prevention paradox. Dr. Gabbett posits that an athlete accustomed to a high chronic workload will respond to a high acute workload with increased fitness, performance, and resilience to injury.1 On the other hand, an athlete who is not accustomed to a high chronic workload will respond to a high acute workload with fatigue, impaired performance, and increased injury. Emerging data supports Dr. Gabbett’s claims about the relationship between acute:chronic workload ratio and injury.

The Workload ‘Sweet Spot’

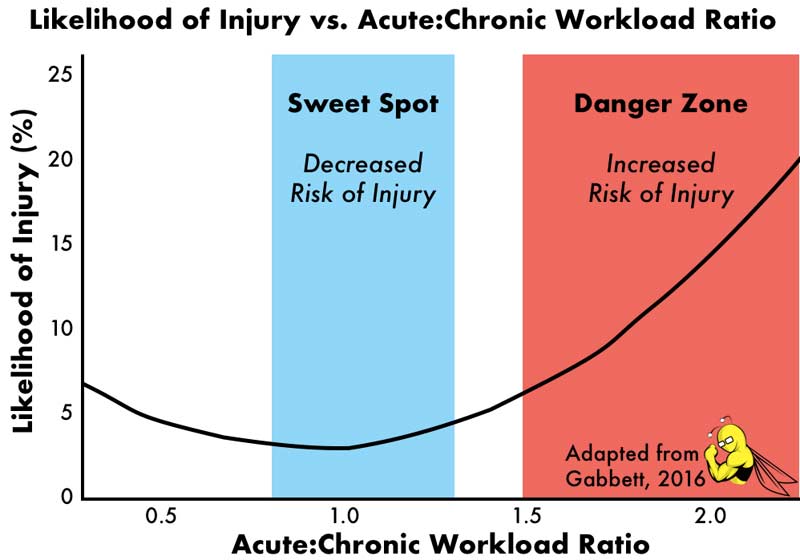

An explosion of recent work in a range of sports (e.g., cricket, soccer, rugby, Australian football, basketball) has shown increased injury incidence is in fact associated with spikes in the acute:chronic workload ratio.19-23 Across sports, the “danger zone” for increased injury appears to be acute:chronic workload ratios over 1.5. Meanwhile, the acute:chronic workload ratio “sweet spot,” which minimizes injury risk, lies in the 0.8-1.3 range.1

Thus, the ultimate solution to the paradox appears to be consistent application of workloads within the sweet spot range. In this way, athletes can progress to high chronic workloads gradually, with minimal load-related injuries along the way. In turn, the high chronic workloads will enhance fitness and performance, further protecting against injury.20

The Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio in Practice

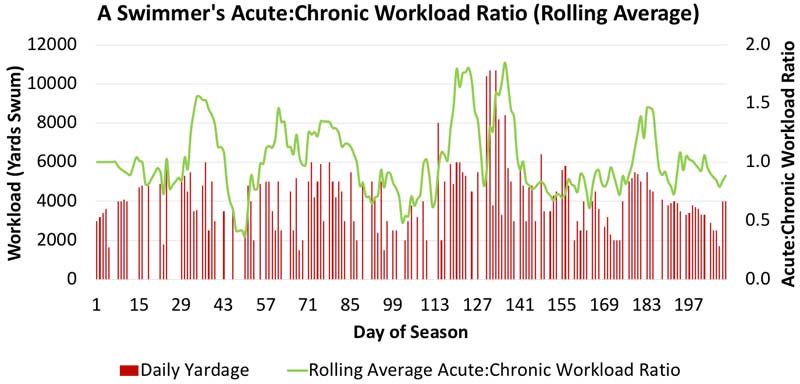

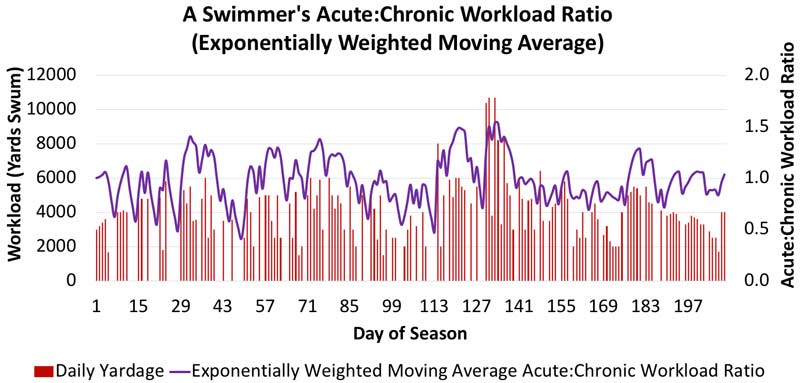

In practice, monitoring an athlete’s acute:chronic workload ratio can be fairly straightforward. Take swimming, for example. The only essential piece of information needed is the swimmer’s daily yardage (an external workload), which the coach or swimmer can supply. From there, rolling averages of the previous seven days (acute workload) and 28 days (chronic workload) can be calculated and divided to yield the acute:chronic workload ratio. Workload data from one swimmer’s 29-week competitive season is shown below.

While much of the depicted acute:chronic workload ratio lies in the 1.0 ± 0.3 range, there are three clear regions with large workload spikes (beginning at Days 34, 124, and 136). Fortunately, this athlete did not sustain an injury secondary to these spikes. It’s important to note in this example that the yardage data doesn’t capture the swimmer’s internal response to the daily workloads. It could be that the upticks in workload were characterized by mostly low-intensity yardage, which may not be as much cause for concern from a fatigue and injury standpoint. To obtain information of this nature, the athlete’s heart rate or session rating of perceived exertion would also have to be monitored.

The #AcuteChronicWorkload ratio model has implications for athletes that span the entire season, says @trpollen. Share on XDr. Gabbett’s Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio Model has implications that span the entire season. During pre-season screening, it flags athletes who are at risk based on low off-season chronic workloads.24 During the competitive season, the model improves our ability to manage workloads, which could reduce injury incidence and enhance performance. For an athlete with an injury, the model assists sports medicine practitioners in return-to-play decision-making.25 By gradually increasing the athlete’s workloads to pre-injury levels, it prepares them to return to play while avoiding re-injury.26

As Always, More Research Is Needed

While a lot of high-quality research has already been conducted in this area, there remains much to learn about acute:chronic workload ratios. Investigators have often selected one- and four-week acute and chronic workload windows, respectively. However, more work is needed to determine the merits of shorter and longer time frames for both acute and chronic workloads.1

In addition, over the past year, the best method for calculating the acute:chronic workload ratio has also been hotly contested. A potential limitation of the rolling average method is that it doesn’t account for the diminishing effects of training over time. For example, a workload imposed three weeks ago gets the same weight in the rolling average chronic workload as one from the previous week. For this reason, some authors favor an exponentially weighted moving average, which weights more recent workloads more heavily than older ones.27,28

To illustrate the difference between the two methods for calculating the acute:chronic workload ratio, we can take the same swimmer’s data from above and apply the exponentially weighted moving average. The two methods yield similar but slightly different results for the acute:chronic workload ratio. As shown below, using the exponentially weighted moving average method, the magnitude of each of the three workload spikes from the rolling average method drops substantially. More research is needed to determine which method is best for predicting injury.

Lastly, the vast majority of the work thus far has been conducted in field and court sports. To add to the data from cricket, soccer, rugby, Australian football, and basketball, more research is needed in diverse sports populations. In particular, different athletic populations may exhibit different acute:chronic workload ratio sweet spots. Although the 0.8-1.3 range is the current best available evidence, we must be cautious in extrapolating current findings to other, as yet unstudied, sports.1 In addition to studying more sports, replication studies and randomized controlled intervention trials are needed to further validate the Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio Model.29

Building on the Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio

Given what we already know about the acute:chronic workload ratio, it represents an exciting evolution in our understanding of the relationships between training, performance, and injury risk. Based on the available evidence, workload monitoring appears to be a crucial component of injury risk assessment. Yet workload spikes certainly aren’t the only risk factors for athletic injury.

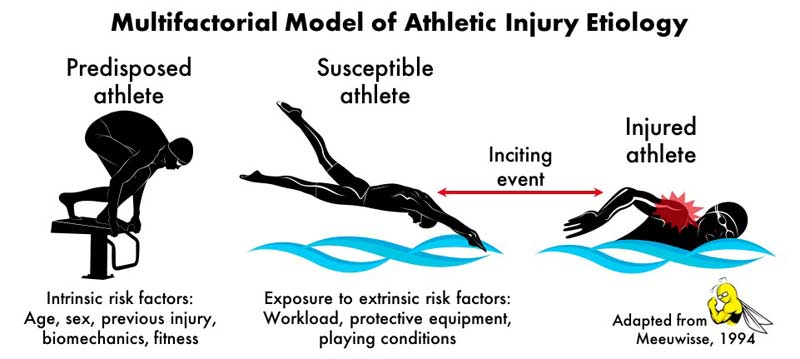

Based on the evidence, workload monitoring seems to be a crucial part of injury risk assessment, says @trpollen. Share on XWhat the Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio Model doesn’t account for are the myriad intrinsic risk factors that can predispose an athlete to injury, such as age, sex, previous injury, biomechanics, and cardiovascular fitness.30 To more fully describe an athlete’s injury risk, a multifactorial injury prediction model would be needed, including intrinsic risk factors as well as workloads.

As it just so happens, Dr. Gabbett has been involved in a more comprehensive modeling effort with the recent “Workload–Injury Etiology Model.”2 This new model advances the idea that the athlete’s predisposition for injury is not static. Instead, his or her intrinsic risk factors are constantly being modified by fitness and fatigue adaptations to previously imposed workloads. In this way, this model highlights the importance of repeated player testing (e.g., of strength, power, conditioning) throughout the season, not just in the pre-season.

Training and competition workloads don’t exist in a vacuum, either. The above-described workloads also don’t account for all the potential stressors in an athlete’s life. Additional stressors like nutrition, sleep, interpersonal relationships, academic demands, and travel can all impact an athlete’s workload response.31 To characterize an athlete’s status more completely, practitioners should also consider collecting ongoing objective or subjective measurements of stress, recovery, well-being, and readiness.32 Options here include daily assessments of grip strength, resting heart rate, heart rate variability, and self-reported wellness questionnaires.

This multipronged monitoring approach may be just what athletes need to train more without injury, says @trpollen. Share on XThe sports science professional should closely observe athletes for physiological and psychological signs and symptoms of fatigue and under-recovery using the above objective or subjective measures, especially in the presence of intrinsic risk factors and workload spikes. A heads-up to the rest of the team staff about the data and its potential implications for injury may be warranted, along with strategies for temporarily reducing workloads and promoting recovery. Indeed, this type of multipronged approach to monitoring may prove to be exactly what we need to train more without getting hurt.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

- Gabbett, TJ. “The training-injury prevention paradox: Should athletes be training smarter and harder?” Br J Sports Med. 2016; 50(5):273-280.

- Windt J & Gabbett TJ. “How do training and competition workloads relate to injury? The workload–injury aetiology model.” Br J Sports Med. 2017; 51(5):428-435.

- Jones CM, Griffiths PC & Mellalieu SD. “Training load and fatigue marker associations with injury and illness: A systematic review of longitudinal studies.” Sport Med. 2017; 47(5):943-974.

- Banister EW, Calvert TW, Savage MV & Bach T. “A systems model of training for athletic performance.” Aust J Sport Med. 1971; 7:57-61.

- Morton R. “Modelling training and overtraining.” J Sports Sci. 1997; 15:335-340.

- Gabbett TJ & Domrow N. “Risk factors for injury in subelite rugby league players.” Am J Sports Med. 2005; 33(3):428-434.

- Gabbett TJ, Ullah S & Finch CF. “Identifying risk factors for contact injury in professional rugby league players – Application of a frailty model for recurrent injury.” J Sci Med Sport. 2012; 15(6):496-504.

- Gabbett TJ. “Influence of training and match intensity on injuries in rugby league.” J Sports Sci. 2004; 22(5):409-417.

- Gabbett TJ. “Reductions in pre-season training loads reduce training injury rates in rugby league players.” Br J Sports Med. 2004; 38(6):743-749.

- Gabbett TJ & Domrow N. “Relationships between training load, injury, and fitness in sub-elite collision sport athletes.” J Sports Sci. 2007; 25(13):1507-1519.

- Killen NM, Gabbett TJ & Jenkins D. “Training load and incidence of injury during the preseason in professional rugby league players. J Strength Cond Res. 2010; 24(8):2079-2084.

- Gabbett TJ & Jenkins DG. “Relationship between training load and injury in professional rugby league players. J Sci Med Sport. 2011; 14(3):204-209.

- Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Cutter GR, et al. “Risk of serious injury for young baseball pitchers: A 10-year prospective study.” Am J Sports Med. 2011; 39(2):253-257.

- Gabbett TJ & Ullah S. “Relationship between running loads and soft-tissue injury in elite team sport athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2012; 26(4):953-960.

- Gabbett TJ & Whiteley R. “Two training-load paradoxes: Can we work harder and smarter, can physical preparation and medical be teammates?” Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2017; 12(Suppl 2):S50-S54.

- Buist I, Bredeweg SW, Van Mechelen W, Lemmink KAPM, Pepping GJ & Diercks RL. “No effect of a graded training program on the number of running-related injuries in novice runners: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2008; 36(1):33-39.

- Johnston CAM, Taunton JE, Lloyd-Smith DR & McKenzie DC. “Preventing running injuries: Practical approach for family doctors.” Can Fam Physician. 2003; 49:1101-1109.

- Rogalski B, Dawon B, Heasman J & Gabbett TJ. “Training and game loads and injury risk in elite Australian footballers. J Sci Med Sport. 2013; 16(6):499-503.

- Weiss KJ, Allen SV, McGuigan MR & Whatman CS. “The relationship between training load and injury in men’s professional basketball.” Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2017; 12(9):1238-1242.

- Hulin BT, Gabbett TJ, Lawson DW, Caputi P & Sampson JA. “The acute:chronic workload ratio predicts injury: High chronic workload may decrease injury risk in elite rugby league players.” Br J Sports Med. 2016; 50(4):231-236.

- Hulin BT, Gabbett TJ, Blanch P, Chapman P, Bailey D & Orchard JW. “Spikes in acute workload are associated with increased injury risk in elite cricket fast bowlers.” Br J Sports Med. 2014; 48(8):708-712.

- Erhmann FE, Duncan CS, Sindhusake D, Franzsen WN & Greene DA. “GPS and injury prevention in professional soccer.” J Strength Cond Res. 2016; 30(2):360-367.

- Murray NB, Gabbett TJ, Townshend AD, Hulin BT & McLellan CP. “Individual and combined effects of acute and chronic running loads on injury risk in elite Australian footballers.” Scand J Med Sci Sport. 2017; 27(9):990-998. doi:10.111/sms.12719.

- Drew MK, Cook J & Finch, CF. “Sports-related workload and injury risk: Simply knowing the risks will not prevent injuries: Narrative review.” Br J Sports Med. 2016; 50(21):1306-1308.

- Blanch P & Gabbett TJ. “Has the athlete trained enough to return to play safely? The acute:chronic workload ratio permits clinicians to quantify a player’s risk of subsequent injury.” Br J Sports Med. 2016; 50(8):471-475.

- Morrison S, Ward P & DuManoir GR. “Energy system development and load management through the rehabilitation and return to play process.” Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2017; 12(4):697-710.

- Murray NB, Gabbett TJ, Townshend AD & Blanch P. “Calculating acute:chronic workload ratios using exponentially weighted moving averages provides a more sensitive indicator of injury likelihood than rolling averages.” Br J Sports Med. 2017; 51(9):749-754.

- Williams S, West S, Cross MJ & Stokes KA. “Better way to determine the acute:chronic workload ratio?” Br J Sports Med. 2017; 51(3):209-210.

- Bahr R. “Why screening tests to predict injury do not work — and probably never will…: a critical review.” Br J Sports Med. 2016; 50:776-780. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096256.

- Meeuwisse WH. “Assessing causation in sport injury: A multifactorial model.” Clin J Sport Med. 1994; 4:166-170.

- Quarrie KL, Raftery M, Blackie J, et al. “Managing player load in professional rugby union: A review of current knowledge and practices.” Br J Sports Med. 2017; 51(5):421-427.

- Gabbett TJ, Nassis GP, Oetter E, et al. “The athlete monitoring cycle: a practical guide to interpreting and applying training monitoring data.” Br J Sports Med. 2017; 51:1451-1452.