Not everyone can have 10+ squat racks and platforms with all the bells and whistles like Tendo units, safety squat bars, and Freelap timers. Many coaches work in a situation where the budget is small and equipment is limited.

I wanted to write this to provide my personal experience working at small schools and making do with what was provided. Explaining how I made it work may help other coaches utilize everything they have at their disposal to provide the best program they can for their athletes.

My Coaching Situation

Before recently getting a job with EXOS to train military members at Fort Bragg in North Carolina, I worked as the Strength and Conditioning Coach for Western Technical College’s baseball team in La Crosse, Wisconsin. In my prior experiences at Saint Mary’s University and Winona State, I learned how to make do with limited space and/or equipment.

Saint Mary’s had three squat racks with attached platforms, a rack of dumbbells, 1-2 back extension machines, four lat pulldown/seated row machines, a few pairs of resistance bands, and some stability balls. Down the stairs from the weight room were the indoor track and rubber-floored basketball courts, which was a great space for speed and agility training (when in-season teams weren’t using it). As you can tell, there wasn’t much weight room equipment for the 250-300 athletes that needed it.

It was a very similar scenario at Western Technical College. They had two squat racks with attached platforms, a rack of dumbbells up to 100 pounds (with only two benches), a rack of kettlebells, stability balls, bands, a couple machines, one glute-ham device (GHD), and one cable machine. Their small basketball court where they do their warm-ups and plyometrics was up the stairs from the weight room. I trained about 40 baseball players, separated into two groups of 20, in this space at 6:00 a.m. and 7:00 a.m. on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. I was the only strength coach during their training, so it was my responsibility to make sure guys trained effectively and safely with the limited space and equipment.

Based on these experiences working with limited staff and equipment, I’ve compiled three tips that ensure everyone can do their workout within an hour, says @Mccharles187. Share on XBased on these experiences working with limited staff and equipment, I’ve compiled three tips I’ve found useful. These ensure everyone can do their workout within an hour, efficiently using our limited equipment to obtain the adaptations and results we need to promote speed, power, strength, hypertrophy, or work capacity, depending on the time of year and goals for the athletes.

1. Pairings Are Your Friend

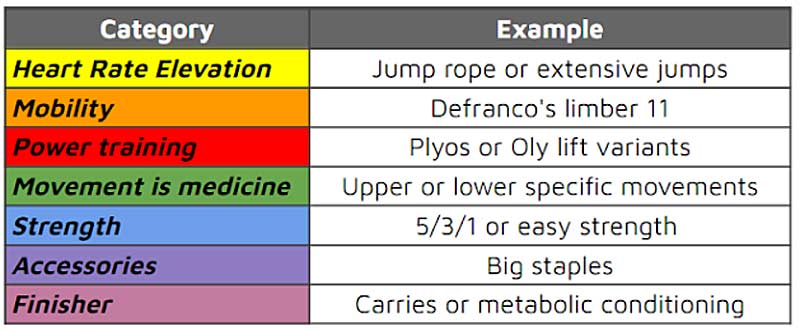

This is an easy and effective way to avoid athletes standing around waiting for equipment. Combine exercises in pairs, trios, or even quads, have your athletes in groups of 3-4 ,and rotate through those pairings before moving on to the next group of exercises. Generally, I like to do combos of three that include:

- A1. Lower body push

-

A2. Upper body pull

A3. Lower body mobility drill

- B1. Upper body press

-

B2. Lower body pull

B3. Upper body mobility drill

- C1. Accessory

-

C2. Accessory

C3. Accessory

Using this setup, I can have groups of three athletes per station where one athlete does the first exercise, one does the second exercise, and the third does the mobility drill. If I have a group of four, that fourth will be the spotter/getting ready to do the first exercise. Then they will rotate through A1-A3 before moving on to B1-B3 and C1-C3. With my 20 guys, I will have two groups doing A’s, two groups doing B’s, and 1-2 groups doing C’s—then, they all rotate accordingly. As much as I like to have them do it in order, it’s just not realistic or efficient. Work with what you have.

2. One Exercise Per Piece of Equipment

This is huge—only use one exercise per piece of equipment. This ensures that everyone will have access to equipment without waiting. If we use the above examples, it will look like this:

- A1. Barbell back squat

-

A2. Chin-ups or v-grip pulldowns

A3. 90-90 rotations

- B1. DB military press

-

B2. Split-stance KB RDL

B3. T-spine rotations

- C1. Band pull-aparts

-

C2. Mini-band monster walks

C3. Planks

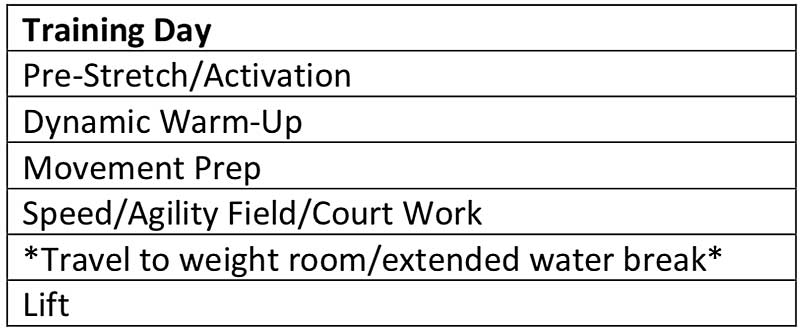

As you see in the above workout, every exercise has its own equipment, because if I had used DB military press with DB RDLs there wouldn’t be enough dumbbells to go around. The way I set up my sessions is this: In our basketball court, we start with our dynamic warm-ups (about five minutes) followed by a pairing of a lower body plyometric with an upper body plyometric (medball-related exercises). Athletes get into groups of 2-3 to get through the plyos within 10 minutes. At this point, the session is 15 minutes in, so afterward we go to the weight room and spend the last 30-35 minutes doing our main training for the day.

When I program for the weight room, I note how many pieces of equipment I have and what pairings would be good together to keep things efficient, says @Mccharles187. Share on XWhen I program for the weight room, I note how many pieces of equipment I have and what pairings would be good together to keep things efficient. In my mind, I want to accomplish a squat, hinge, upper press, upper pull, 2-3 mobility drills (at least one upper and one lower), a core exercise, and a grip/wrist exercise. This was a baseball team, so my accessory/mobility drills were more baseball-specific with thoracic mobility, hip mobility, wrist/grip strength, and scapular/rotator cuff stability/mobility.

I usually think of what barbell exercises I want to do first, since I think these will be my biggest bang for the buck, and pair them with something simple that can be done within the area of the squat rack/platform, so everyone can rotate in. For example, on Mondays I programmed back squats with chin-ups and a lower body mobility drill because our chin-up bar was next to our racks and it was easy to walk over and do them—and the mobility drill can be done anywhere, since you don’t need equipment for them most of the time. Because each exercise used a different piece of equipment (or no equipment), I never had athletes waiting in line for something, and they did my go-to exercises to promote power and strength (as well as mobility, which made it easier for them to get their squats to depth after each set).

Following that, we did an upper press paired with a rotator cuff exercise and a thoracic mobility drill: an example would be a single arm upright kettlebell press with band pull-aparts with chicken wing thoracic rotations on all fours. Our next pair would be a hinge exercise paired with a core exercise with another lower body mobility drill. Because we used a barbell and a kettlebell already for back squats and our upright press, I’d use a dumbbell and do an RDL variation with bird dogs and 90-90 rotations. Finally, we’d finish with a grip exercise like farmer’s carries to end the session.

This is the summation of the workout:

(In gymnasium)

- Dynamic warm-up: 5 minutes

- Plyometrics (if you like Olympic weightlifting, you could do this here instead): 10 minutes

- Lower body plyometric (depth jumps off a box) 3-4 x 3-5 reps

- Upper body plyometric (medball slams) 3-4 x 6-10 reps

(Head to weight room)

- Weight room: 30-35 minutes

- A1. Back squat APRE 10 (3 warm-ups sets, 2 workings sets)

-

A2. Chin-ups 5 x 3-5 reps (add weight as needed)

A3. Lunge-position stretch 5 x 5 belly breaths

- B1. SA half kneeling kettlebell upright press 3 x 8-12 each (great for baseball for shoulder stability and overall grip)

-

B2. Band pull-aparts 3 x 8-12 each

B3. Quadruped chicken wing thoracic rotations 3 x 8-12 each

- C1. Dumbbell split stance RDL 3 x 6-10 each

-

C2. Bird dogs 3 x 8-12 reps each

C3. 90-90 rotations 3×10 each

- Farmer’s carry 3 x 30 yards

This was a workout I did with my baseball players, and I found it very effective. We were in an early off-season phase during the fall semester, so the reps/volume was very high. As the semester progressed, we worked our way down the rep range to focus on strength (3-6 reps of 4-5 sets or APRE 6) and then eventually peak strength (1-4 reps of 4-5 sets or APRE 3).

In short, one exercise per piece of equipment. Use that creative mind!

3. Identify Your Focus Exercises

Focus on 1-2 main exercises that you want to coach and check technique, then pair those with easier exercises that you don’t need to worry too much about. As the only coach on the floor, I couldn’t realistically watch every athlete for every single set and rep and watch them like a hawk. When doing your pairings, pick that one exercise that you want to watch them do and let the other pairings be exercises athletes can confidently do on their own without hurting themselves.

When doing your pairings, pick one exercise that you want to watch them do and let the other pairings be exercises athletes can confidently do on their own without hurting themselves. Share on XIf we use the A pairings again, I’d be looking at everyone’s back squat a lot more than I’d be watching them do chin-ups and mobility drills. In the B pairings, I watched how everyone hinges, because most athletes can military or bench press without screwing up too much. Knowing you can turn your back without worrying someone will hurt themselves while you’re focused on the main exercises will give you a sense of ease and less stress.

Results

The results you can expect from running workouts in this format are athletes getting through their exercises effectively and efficiently without long wait times. You also successfully program exercises that will influence adaptions to reduce injuries and enhance performance with the limited space and equipment you have.

Within the week, during three training sessions at Western Tech, my athletes were able to do their warm-ups, plyometrics, back squats, deadlifts, barbell reverse lunges, RDL variations, chin-ups/pull-ups, upper presses, and row variations, along with mobility and stability exercises—all within 50 minutes, with only two squat racks/platforms, dumbbells, kettlebells, and bands. We even performed APRE training with back squats, deadlifts, and DB bench press and witnessed great results with athletes increasing weight on the bar or dumbbells by 5-10 pounds and/or increasing by 2-4 reps of the same weight on a weekly basis.

We did the simple things really well, and the hard work paid off. My guys were workhorses, and I had to reinforce how to be more of a racehorse focusing on quality over quantity, says @Mccharles187. Share on XWe did the simple things really well, and the hard work paid off. Having my exercise selection with equipment and space in mind helped my athletes get there. Athletes seeing their numbers go up really helped build buy-in to my program, and athletes thanked and fist bumped me, telling me how great a job we were doing. They saw that doing a workout under an hour three days per week, while also focusing on sleep and nutrition (I took wellness surveys of their stress levels, hours of sleep, and body weight before every session to hold them accountable), was giving better results than training five days a week for 1.5-2 hours. My guys were workhorses, and I had to reinforce how to be more of a racehorse focusing on quality over quantity.

Using these three tips, I see no reason you can’t get your team in and out of the weight room within an hour and still get in solid, quality training. It’s about being efficient and setting up a constant, fluid, and well-oiled machine of athletes rotating exercises and pairings. Athletes will pick up on how you set up your stations and get the hang of it quickly. Good luck and get after it!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Matt McInnes Watson is a track and field and performance coach. He has a master’s degree in athletic development and is currently studying for a Ph.D. in plyometrics. Watson is the owner of Plus Plyos, a coaching business that provides supplementary plyometric programs through video format. He is currently teaching in the United Arab Emirates, and he coaches multiple athletes from the U.K. and U.S.

Matt McInnes Watson is a track and field and performance coach. He has a master’s degree in athletic development and is currently studying for a Ph.D. in plyometrics. Watson is the owner of Plus Plyos, a coaching business that provides supplementary plyometric programs through video format. He is currently teaching in the United Arab Emirates, and he coaches multiple athletes from the U.K. and U.S.