I would love to have athletes available to train 52 weeks out of the year—and I’m sure many of you would echo that sentiment. That way, we can have our best shot of implementing the programs that we neurotically designed for our players and their needs. In D1 college athletics, you may get close to this, but even those coaches have to navigate time off and dead periods.

Training, by nature, is incomplete.

As strength and conditioning coaches, we are at best a small sliver of an already overflowing pie. I am not discounting the work that we do; many of us are reading, iterating, listening to podcasts, talking within our network, and exhausting any other avenue in order to put our best foot forward for our players. With that being said, solid training relies on long-term consistency over short-term intensity. Therein lies my problem.

Solid training relies on long-term consistency over short-term intensity. Share on XIf you’ve been in the iron game long enough, you will quickly find out that things never quite go as planned. What was once a meticulously mapped out four-week training block has suddenly become an index card with scribbles and revisions in red ink. This is an all too familiar experience of mine, working at a private PK–12 school. In a lot of ways, it is similar to many public schools, but there are two unique constraints that are central to my demographic:

- Over 80% of students participate in at least one athletic sport. As a school, we rely on and encourage our students to participate in multiple sports.

- There are far more days out of school and dead periods that limit exposures to consistent training.

I am a huge advocate of multi-sport participation: the benefits far outweigh the drawbacks from where I sit. The differentiation between sports and their required abilities are themselves a training means for our students. From a training perspective, this simply requires getting a little creative and dialing in what is realistic in terms of adaptations. This article will help outline some simple, practical training tools that you can use if you find yourself in the same situation. I am a believer that something is still better than nothing at all.

A Mile Wide, An Inch Deep

Strength and conditioning at a secondary school can at times feel like Groundhog Day. Depending on certain circumstances, it might be six weeks or so before you see an athlete again. I’m half-joking here, but the bottom line is, as a coach, I have to be comfortable with uncertainty and have the willingness to adapt on the fly. I’ve experimented with highly-focused training blocks—I felt that if I only have x amount of time, I might as well invest heavily in the target quality that will give me biggest bang for my buck.

Though I had success with this model, I’m not sure it was the best overall package for my athletes. As I transitioned to a more diverse program, I started to see equal if not better results. I also found that athletes enjoyed training much more and didn’t experience the staleness that comes with mind-numbing repetition.

As I transitioned to a more diverse program, I started to see equal if not better results. Share on XI began creating base templates that I could use for my training sessions. Once I have a base template, I can iterate and make adjustments on the fly. Training sessions would be forecasted out on a daily and weekly basis, so I could be flexible whenever I was thrown a curveball. I made templates for:

- Weight room

- Speed training

- Conditioning

I like a concurrent approach to training, so I would utilize these templates almost like a menu at a restaurant: I wanted everything to be present in some form or fashion. Based on the constraints and what our goal was at the time, the distribution of each session type would change. Let’s look at how I set up weight room work for my athletes.

Weight Room

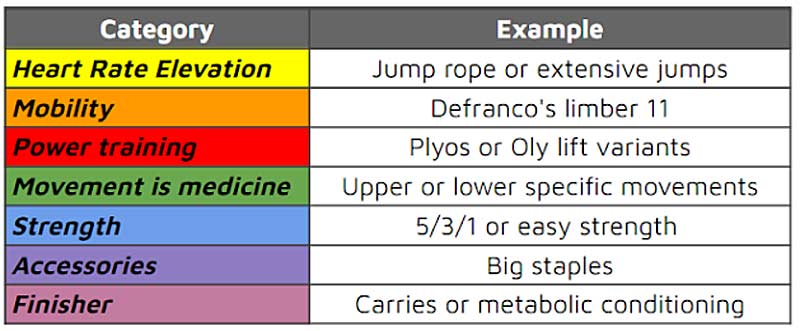

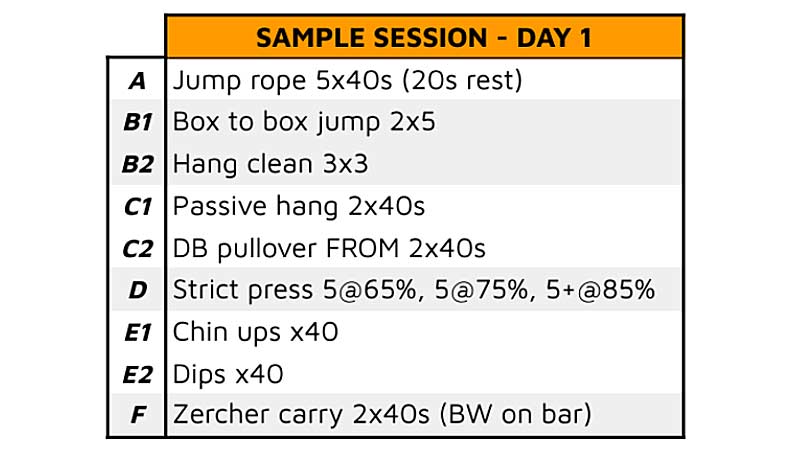

In the weight room I had to be simple. Simple in this case doesn’t mean easy. I wanted to have a training menu in place that took little time to teach, but still ticked off a lot of boxes. Here is my basic outline of what a session could look like.

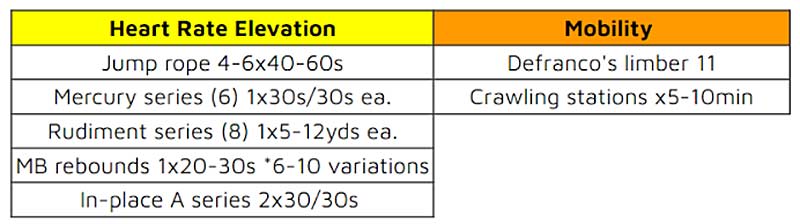

Heart Rate Elevation

Now let’s get through each category and I will show you some specific movements that I like to use. We start off every weight room session with some form of heart rate elevation. I like to use jumping rope or extensive jumps for this period. Not only do they raise heart rate, these jumps also help with elasticity, stiffness, and coordination of the lower limbs. These are done regardless of upper or lower emphasis. On upper body days, I might incorporate extensive medicine ball throws in this initial period or put them in as a primer before a main lift. Here is an example training menu that I pull from.

Mobility

The next phase of the workout will focus on mobility. I am guilty of neglecting mobility in my programs—I always thought there were other things that needed to be done that were of a higher priority. It wasn’t until I started adding in some mobility exercises into my own sessions where I could see a huge difference in my performance. Not to mention my body felt a ton better.

For my purposes, I am not trying to reinvent the wheel. Joe Defranco has a short and sweet mobility routine called “Limber 11.” It goes through some foam rolling, stretches, and range of motion drills that can prepare the body for training. The circuit works, so I use it. Every so often I will add in some crawling to shake things up. While crawling is not technically mobility driven, it does have a stability component along with many other benefits. Five to ten minutes is all you need here.

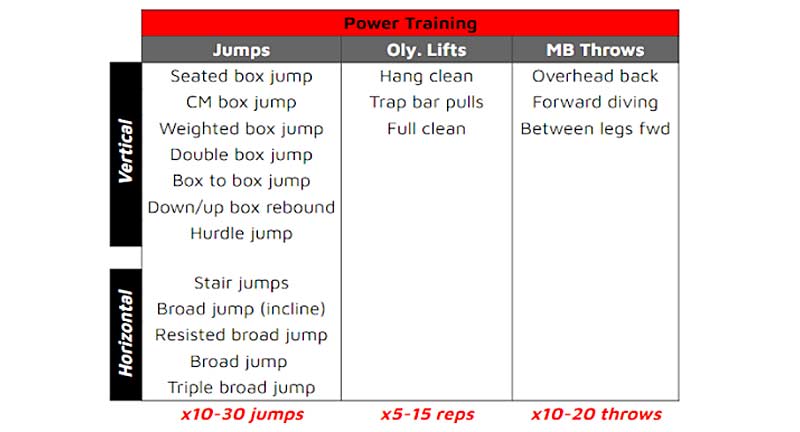

Power

Once we finish up the initial warm up, I have the athletes perform some power-type activities. The movements during this period can be any type of jump, plyometric, Olympic lift variation, or medicine ball throw. Jumps/plyos are always included. The Olympic lifts or medicine ball throws will be the secondary choice.

Typically, the prescription will be based on the sport, the athlete, what needs to be addressed, and training logistics. For the inconsistent athlete it is best to err on the side of caution. If I get an athlete of very low training age, I tend to always pick jumps. You can get a lot out of 15-20 quality, coached-up box jumps. If I see an athlete who has accumulated training sessions, I will dose hang cleans—light and fast cleans will reinforce technique and give us the primer power work that we want. Again, reps stay in the 10-20 range. Quality over quantity.

For the inconsistent athlete it is best to err on the side of caution. Share on XEarly in my coaching, Olympic lifts were a no go for me. I always felt that it took too much time, and quite frankly I wasn’t extremely confident in teaching them. What changed my mind was hearing great coaches like Al Vermeil, Dan John, and others speak about the benefits, along with how to progress the lifts. Like many things, I started with myself. After about four weeks, I felt polished enough to where I could train using a hang clean. From a performance and overall well-being side of things, adding these Olympic lift variations was a big net positive. Not to say they should be done with everyone, but it’s worth exploring and talking to coaches about. Here is an example breakdown of:

- What movements make up this period.

- How they are progressed throughout training.

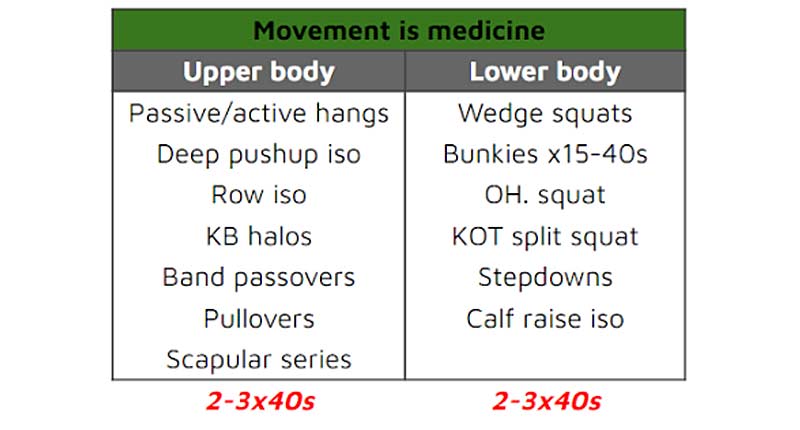

Range of Motion

At this point in the session, the athletes are warmed up and primed for the main lifts and our “meat and potatoes.” During their main lift work up sets, I like to add in one to three movements to help with range of motion and overall integrity of specific body regions. I like to call these add-ins movement is medicine. These are done at relatively light intensity and the main goal is to grease the groove. Typically, I prescribe time instead of repetitions. It is also a good chance to put a tempo cadence on the repetitions to further time under tension and muscular work.

Here is a list of some of my go-to upper and lower body movements. I choose these for inconsistent athletes because they:

- Are extremely easy to teach.

- Require little equipment.

- Can be done alongside their main lifts.

- Address common movement issues that I see in my population of athletes.

- Strengthen supportive structures that would take up too much time on their own.

- Can aid in the warming up of specific musculature needed in the main lifts.

Strength

For our strength work I keep it very simple. Sorry if you were looking for some Russian top-secret, double probation program, as Buddy Morris would say. The two best programs, in my opinion, are Jim Wendler’s 5/3/1 and Dan John’s Easy Strength. These programs trim the fat and are as essentialist as it gets for training. As long as you have a push, pull, hinge, and squat somewhere in your training, you will be fine.

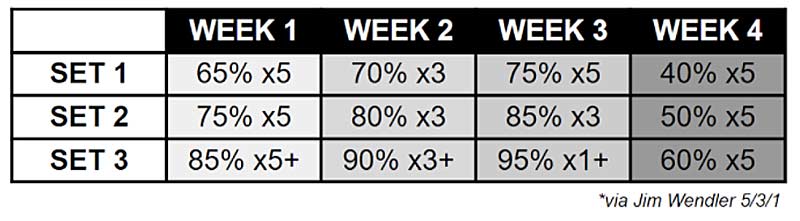

As long as you have a push, pull, hinge, and squat somewhere in your training, you will be fine. Share on XBoth programs treat strength as a skill. You complete every rep in training and you “own” every rep. You can study up on both of these by clicking on the links above. I will provide the base template for 5/3/1 in terms of percentages. I like a total body approach, but strength work can easily be split into upper/lower. If you want to get fancier and your athletes are developed enough, you can adopt a Westside-style approach.

At this point in the session, the athletes have done a good bit of work. Training sessions using this approach tend to be a little on the longer side, but the volume associated with this program is built in a way that isn’t very taxing to athletes. This program is meant to accumulate repetitions from a variety of movements and planes of movement.

Since a program like this spares precious resources of the body, intensities of the main lifts can be programmed in waves. Once athletes become skillful at the lifts, then you can make trips up above their true 85% 1RM more often. For younger athletes, I will be overly safe when determining rep max ranges. I would rather them be too low than too high with their weight. A majority of early adaptation will be through the nervous system in the first place, so rep execution is crucial. I am a firm believer that this is a well-rounded GPP program that can be implemented to both prepare athletes for the season as well as train them during the in-season period.

For younger athletes, I will be overly safe when determining rep max ranges. Share on XAccessory Lifts

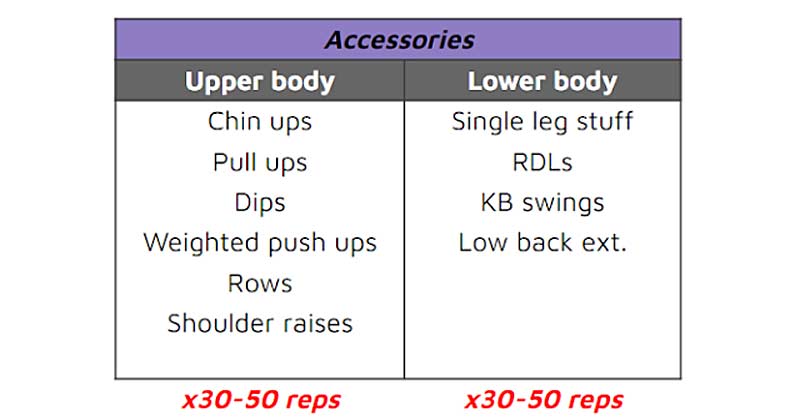

When it comes to accessory lifts, I pick those that give the most bang for your buck. Sure, I will add in some neck, traps, arms, and calves every once in a while—however, in my experience, athletes will end up doing this stuff on their own anyway. Don’t pick too many accessories, maybe just two or three depending on the session. Here are some of my favorites. Again, I choose these most often because they are no-fluff and they are effective as accessories to the main lifts.

Finisher

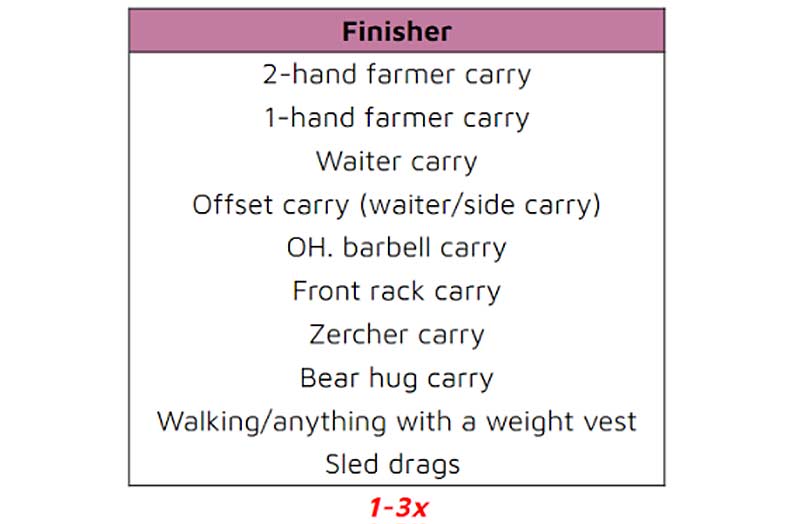

To cap off a session, more times than not I have athletes do a “finisher.” This isn’t your workout-of-the-day lactate-fest. All parties enjoy the finisher so that’s a win. My go-to is always a carry variation. Dan John talks about anaconda strength. Being able to brace and stabilize is important, especially under fatiguing conditions. Distances or times don’t have to be crazy—just enough for the athletes to feel it. They should leave the gym feeling good. Even if they grinded through it, they leave with a sense of pride.

Being able to brace and stabilize is important, especially under fatiguing conditions. Share on XA recent conversation with Al Vermeil has opened my eyes to the importance of mental conditioning—if athletes believe they are working hard and you are gradually increasing that work over time, a winning culture has the soil to grow. As a coach, you have to keep them going up to a level that they never thought they could reach. But you have to be smart about it.

Other things I use are prowler pushes, rower machines, battle ropes, grip challenges, and long duration iso holds. Here are some of my favorite carries.

Final Thoughts

So, there you have it. A typical training session I would run that touches on a lot of different things. Sure, it doesn’t follow a neat periodization scheme; it does, however, give the athlete sound training and it also keeps them excited about coming back.

A perfect plan is useless if you have no one to use it with. Share on X

A perfect plan is useless if you have no one to use it with. If you coach athletes that are in and out due to school, sports, and family, then this is for you. It is hard to run a block system or a concurrent methodology if you only get four weeks here and four weeks there with athletes. When time is the enemy, any quality work is good work. It also gives you chances to try out new training methods. In my experience, young athletes love to be the guinea pigs as long as you explain to them what, how, and why. My speed and conditioning work would follow that general outline. The key is to not overcomplicate things. Exercise prescription and workloads are still based on common sense principles.

Give the athletes what they need and what they are ready for. A rule of thumb from coach Charlie Francis is looks right, flies right. You’ll know when changes need to happen. If it doesn’t work, reassess and find a new path.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF