One of the biggest disparities between training and competition is that failures in either affect us in different ways. All mistakes are learning experiences; honestly, mistakes are probably the best way to learn. However, mistakes can also cost you a win—so there’s value in practicing perfection.

The chaos, high stakes, and intensity of a game can never be replicated in practice or training, but there is value in bringing a game-like mindset to training. We want perfection in games, so we should train to that same standard. Sometimes in training, then, we need to add more pressure. Higher stakes. Velocity-based training (VBT) is one way that I’ve been able to do that.

In training, every rep counts, and VBT is a tool to quantify that. Using VBT without a true strategy for bar speed or data collection defeats the point of using VBT in the first place.

Teaching athletes the importance of hitting these bar speed zones attaches a “winning opportunity” to the rep. That attaches intent, accountability, pride, and even a little bit of pressure to each rep an athlete attempts.

I think a lot of athletes can use these pressure situations (albeit low-pressure) to grow mentally—aside from the obvious physical adaptations. We need our athletes to have the mindset that missing a target bar speed is on the same level as missing a layup or losing a fumble. It costs us a winning opportunity.

This is not a mindset that every athlete can (or should) accept right off the bat, or even at all. It takes a lot of coaching, rapport building, and trust between coach and athlete. It also takes the right athlete. Using VBT doesn’t make you special or advanced in any way. It’s still our responsibility as coaches to use our best judgment on who, what, when, where, and why to implement any and all tools.

Just like in sports, not every practice is a perfect practice. We can’t win every single game. We won’t hit every single rep in the right velocity range…but the applied pressure of doing so and objectively knowing the data on each rep is truly an underrated component of VBT.

Training = Testing = Training

The purpose of training is to achieve some sort of positive outcome for the athlete. With the amount of technology available, coaches and athletes no longer have to guess on whether or not the results are there.

Although testing is vital, it can also become a distraction. Test days or max-out days seem like a great idea on paper, but they often turn into a mess of athletes loading the bar with weight they have no business attempting and grinding out ugly reps just to get their name on a leaderboard nobody has cared about since 1996.

Or, even worse, it becomes an all-out BROnanza fueled by caffeine, ammonia caps, and EDM music, resulting in overly inflated maxes that nobody in their right mind could ever repeat again without the same stimulus, which ruins the next training block because it’s based on fabricated training maxes.

I’ve always felt, even as an athlete, that a specified testing day was bogus. The beauty of VBT is that the test IS the training, and the training IS the test.

Video 1. You don’t need testing days to hit a PR. Hit them in training.

The test results can come in many forms, such as higher load than the previous week, more reps at the same load as the previous session, higher velocity at the same load as the previous session, or higher power at the same load as the previous session. Sometimes athletes will actually PR in a lift, jump, or sprint in a regular ol’ Tuesday training session without the glitz and glamour of it being a true “test” day.

Of course, athletes will have their off days too, but VBT can help indicate that and allow the coach to dive deeper with face-to-face communication. As a coach, when you know where an athlete’s numbers should be and you’re seeing them fall short of that, it’s easy to just ditch all the tech and help the person in front of you with a face-to-face interaction.

Staying True to VBT Fundamentals

Although this article is mostly about lesser-known VBT benefits, I think it’s important to touch on the fundamentals of VBT as well. Velocity-based training is pretty much what it sounds like: training that is based upon the velocity of the load being moved rather than on the percentage of a 1RM, as is typically used.

SAID Principle

VBT complements a universal staple in all of training, which is the SAID Principle (Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands). This concept simply means that when the body is placed under a specific form of stress, it will make adaptations to that form of stress to be able to better withstand that stress in the future.

The beauty of VBT is that it can really help pinpoint what demands you need to impose, and it allows you to objectively track those demands stressed over the course of a training program.

If an athlete’s 1RM is 225 and the program called for 80% of that, the load will be 180 no matter what. An athlete’s performance of those 180 pounds could vary by up to 15% on any given day. That means they could perform reps 15% faster or 15% slower, or even 15% fewer reps. Those variables change the stress imposed by the program.

Conversely, if you prescribe a bar velocity—say, .50 m/s—the load is no longer a set-in-stone amount. You know that .50 is a comfortable bar speed for 80% 1RM for 6-8 reps, and if the athlete begins to get too far away from the prescribed velocity, you can make the load adjustments necessary to keep them in the sweet spot.

This makes sure you are really getting close to that desired adaptation even with all the variables that athletes face day to day such as fatigue, stress, stomachaches, toxic relationships, and any of the other factors that affect performance.

Control What You Can Control

Speaking of performance-changing variables, I’ve got some terrible news: WE CAN’T CONTROL THEM ALL.

Just as we tell our athletes to control what they can control, we need to do the same as coaches. We see our athletes for 1-2 hours a day if we’re lucky. Outside of that, they have their own life to live, and we never know exactly how that looks.

Accumulating VBT data over time makes it very simple for coaches to see trends in performance and identify red flags when those trends start to deviate in a negative way. On the other end of the spectrum, it also can help coaches find “green” flags: meaning, times we can put our foot on the gas.

Obviously, people skills and building a relationship with the athletes both go way further here, but the data is a nice bonus. Since VBT can be used as a readiness indicator, it’s a great tool for managing the stresses an athlete will endure when they’re with you in training.

VBT isn’t always going to expose poor recovery or readiness; sometimes it will reveal that athletes can push themselves harder than their current level of training. That alone is worth the price of any of these units.

Load-Velocity Profiling

Perhaps the most beneficial aspect of VBT is the ability to individualize programming based on an athlete’s load-velocity profile. This allows coaches to precisely prescribe loads, percentages, bar speed, etc. based on the athlete’s own unique profile.

I really like to get a profile on our athletes for what their “main” lifts will be over their training program. Things like deadlift, squat, and bench press variations are always a great option here.

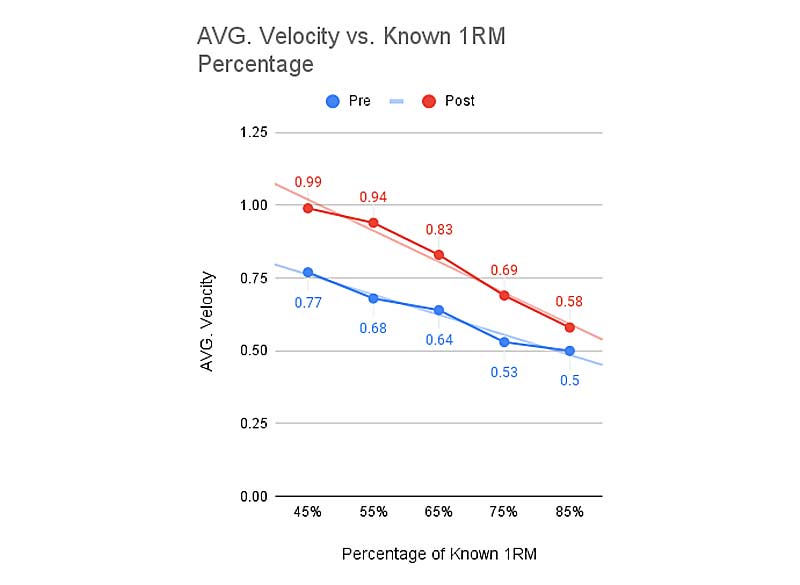

We take an athlete through three to five sets of 35%, 45%, 55%, 65%, 75%, and 85% of their known or estimated 1RM on any given lift. As the load goes up, the velocity will drop, creating a force-velocity curve completely customized to that athlete in that specific lift.

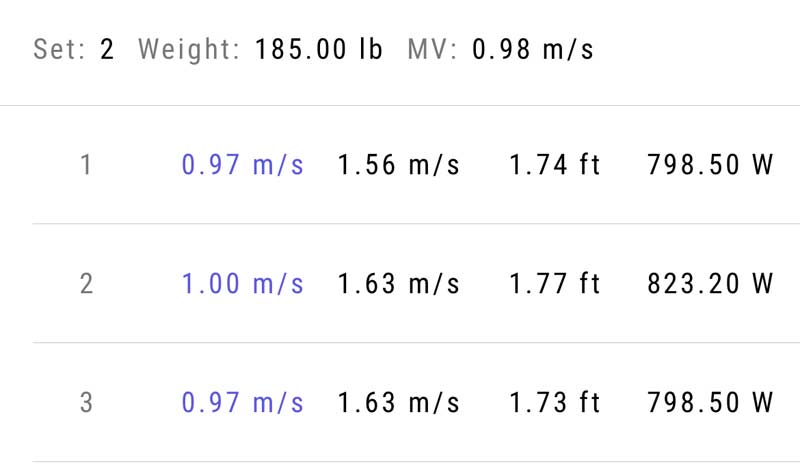

There are various methods for completing this assessment, but I have found that using the set average velocity gives us the best data. We also allow the athlete to choose between three and five reps based on how they feel.

This profile can not only predict an athlete’s 1RM but also shows coaches where an athlete may lack consistency along the load-velocity continuum. Perhaps they moved 35% and 55% at around the same speed? This would lead me to believe they lack rate of force development and can benefit from training to help them learn how to produce force more quickly against lighter loads. Maybe they are weaker than expected and the 85% set moves entirely too slow or for not enough reps? This could indicate that a strength phase may be beneficial for the athlete.

These are just two common generalized examples, but the beauty of load-velocity profiling is that it is a 1:1 blueprint tailored to the athlete and their specific needs. Any changes to that profile reflect changes in that athlete, which is exactly what we’re trying to achieve.

These are incredible tactics we can employ with our athletes, but there are numerous resources out there that focus on each of them specifically. Again, I want to get back to talking about the benefits of VBT that rarely get discussed.

Always Connected

One last and extremely underrated benefit of VBT is that it’s technology based. One of the biggest myths and misconceptions about using technology in coaching is that it is somehow a “distraction” to the athletes.

I could not disagree more with that viewpoint.

It’s 2021. Kindergartners learn with iPads in school. Technology is literally ingrained into our culture. At this point, technology is normal—NOT using technology is abnormal.

I think coaches have the ability to make VBT work in all settings. It’s definitely quite a bit easier to implement in the private sector than in a team setting, but I’ve had success doing both. It’s all about how you present it and educate the athletes on it and, most importantly, if you truly give it a fair chance to “work.”

We should also consider the athletes we’re working with. Most of the current athletes today are Generation Z. These are athletes born between 1995 and 2012. That includes everyone from the kid learning how to lift for the very first time to current professional all-stars and MVP award winners. No tool is more widely accepted and utilized than technology for this generation of humans. Generation Z is not only tech-savvy, but they’re also borderline tech-dependent. In many ways, I’ve seen technology in training connect the dots for athletes in some situations more clearly and thoroughly than I could do by explaining.

As coaches, we adapt our programs, exercise selection, volume, and intensity to the needs of the athlete. I think we need to also consider that we should adapt our delivery of these methods to the current age of athletes as well.

Altogether, VBT is an incredibly valuable tool for coaches to continue to maximize our time spent with athletes. It’s not about having cool equipment or being the person with the most data in the room. It’s about being the person who can have the greatest impact on those who they work with and utilizing any means necessary to do so.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF