An athlete of mine finished their sprint and immediately looked back at me and said “Was that a PR [personal record]?” I said “No, it was not,” then registered the disappointed look on their face. Keep in mind, this athlete is only 10 years old (but very athletic and very competitive). I know this is not a healthy mindset for speed training and athletic development, so I need a solution to this problem.

PR-itis is a term my colleagues and I have coined to explain the belief that any training rep that is not a PR is a wasted training rep. PR-itis stems from the story athletes tell themselves about the process of progress—it is an unrealistic set of expectations about what the process of progress in athletic development really looks like.

PR-itis is a term my colleagues and I have coined to explain the belief that any training rep that is not a PR is a wasted training rep, says @CoachBigToe. Share on XThe root of this issue is that numbers are easy to understand and that the process of progress does not always follow a linear track. Those factors, combined with the amount of technology and instant data available these days, can lead to athletes misunderstanding the context for their own training data, which sets the stage for PR-itis. It is important for athletes to understand that in the process of progress, PRs will not happen every day—but there are still other objective measures of progress.

My athlete and I then had a conversation where I showed him a range of numbers, looking at both their PR and what 95% of their PR is. Next, I explained that that is our range of what is considered a high-quality, high-intensity rep for speed gains. The following week, my athlete finished their first sprint and immediately asked “Was that within my range?” (wipes tear away after proud coaching moment).

Imagine how impactful this lesson will be for this athlete years down the road, now that we have addressed their PR-it is and replace it with a new story of what their own progress looks like on a day-to-day and week-to-week basis.

The Origin of 95% Threshold

Developed by legendary speed coach Charlie Francis and adopted by one of his mentees, speed coach Derek Hansen, 95% of a PR is the threshold I have targeted as a high-intensity nervous system stimulus to improve speed. With how objective and instant feedback is with technology, we need something just as objective to help combat PR-itis and create context for our athletes.

The 95% threshold gives an objective way for me as a coach to change the context and expectations of a daily training session.

The 95% threshold gives an objective way for me as a coach to change the context and expectations of a daily training session, says @CoachBigToe. Share on X95% In Real Training Sessions

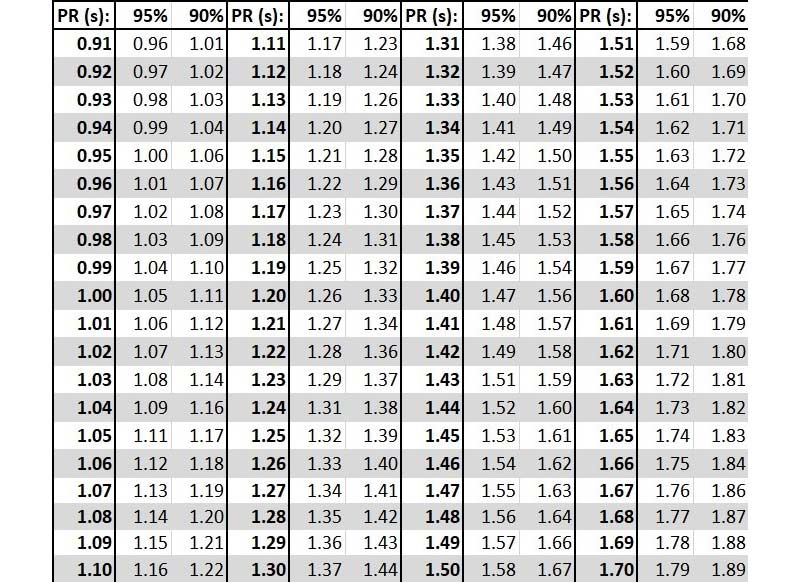

Below is a chart I created in Microsoft Excel (my favorite) that has 95% of a large range of PR’s. I printed this out, laminated it (also my favorite), and taped it to the wall right next to the laser timing gates in the facility where I coach. I use this chart in two primary ways:

- For a quick reference of how to respond to my athlete asking “Was that within my range?”

- A conversation starter in between sprints to educate my athletes on PR-itis.

The 95% threshold also opens up a conversation about the process of progress. I was going through this talk with a group of high school athletes and asked them to list all the factors that contribute to sprinting at 100% and getting a new PR. In the facility I coach at, our main sprint times we test 1-2x a week include a Flying 10-yard sprint and “5-15” acceleration (first and last timing lasers are 5 and 15 yards away from the start line, respectively). Their answers included:

- Sleep

- Nutrition

- The previous day’s training

- Mental readiness

- Motivation

- Playing on 3 soccer teams (in the case of my 10-year-old athlete from before…)

Then I asked “What happens when one or two of those things are off? How often are all those things perfectly aligned?” This was a big lightbulb moment: with all the factors of being an athlete—let alone a student-athlete—PRs probably are not going to happen as often as they would hope. But now they have an objective way to evaluate the process that is not a PR.

With all the factors of being an athlete—let alone a student-athlete—PRs probably are not going to happen as often as they would hope, says @CoachBigToe. Share on XDesigning speed training for my athletes, we are going to sprint and time our sprints every session. The data is consistent, instant, and relevant to their goals of becoming faster. However, only being together for 2 hours of their entire week, there are 168 other hours that can detract from what we are trying to accomplish. PR’s do not (and will not) happen every session, but we need improvement to justify continuing the plan. When life and being an athlete with outside influences affects our training session, 95% is a new gauge of progress that is not a PR.

Getting faster over time is a combination of improved sprinting mechanics and improved neural output. Knowing all the factors that go into sprinting a PR (and everything else my athletes have going on), we can determine progress by improving mechanics and giving our nervous system high-intensity stimuli that will add up over time. This is through knowing that increased performance will come when most of the outside factors align (actually recovering from training, adequate sleep, proper nutrition, etc.).

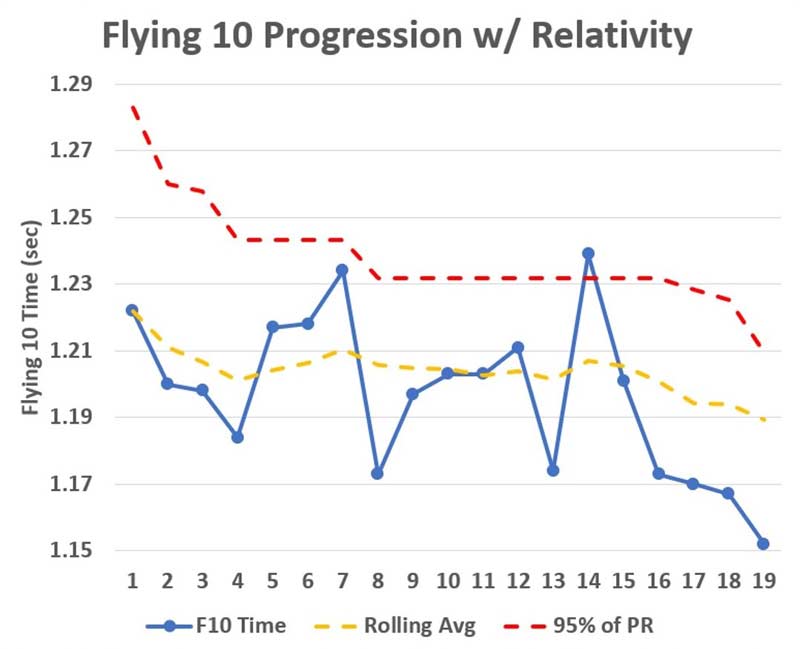

Surprisingly, I have found only 11% of the time my athletes are under 95%, but that is an article for a different day.

Below 95%

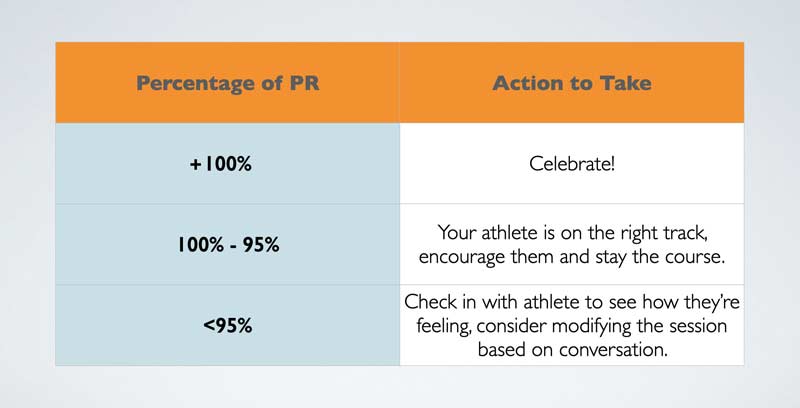

Within our 95% threshold, we also have below 95% and what that means. Just as easily as we can use a percentage of a PR to say “That was great, keep going,” we can also use it to say “Today might not be the best day for speed development” or “That was a little slow, how are you feeling today?”

On a normal training day, my athletes will walk in and I will ask how they are feeling, how was practice, how was school…but their answers never really get too deep. But if my athlete is under 95%, then I will definitely ask more questions.

Let’s say an athlete’s PR for a Flying 10 is 1.235 seconds. If they sprint a time slower than 1.297, I’ll check in with a question and conversation. It could have been that they just “felt” off, that they were thinking about technique too much, or needed that as a final warm-up. If they sprint two times that are slower, I will legitimately consider modifying the training session. It is hard to argue and say everything is okay with how objective the threshold is. However, it is important to open a discussion first with your athlete instead of jumping directly to a decision.

Then, I will learn that my athlete had 4 games in 2 days, they have not eaten anything that day, or they barely slept. These are all important details that athletes sometimes keep to themselves. With this new information, then I can make better decisions as a coach to guide my athlete and the rest of the training session.

One sprint under 95% opens a conversation and 2 sprints will almost always lead to modification. The premise of adapting the training session is that we are playing the long game. One session cannot make or break us, but it can take us in the opposite direction of our goal. How do we get the most out of today to help us achieve our speed goals in the future? What else can we do today that is not max-effort sprinting to help us achieve our speed goals?

One sprint under 95% opens a conversation and 2 sprints will almost always lead to modification, says @CoachBigToe. Share on XThe answer is mechanical work, active recovery, and/or sub-maximal lifting to set us up for success in the NEXT training session.

This is easier said than done, especially when dealing with one (or a few athletes). Within big groups, the issue is singling out a few athletes to stop training or do something different while everyone else continues. And that is always the issue with bigger groups: quality control. Understanding the dynamic of an athlete being in a group, assuming there would only be 3-5 timed sprints anyways, let them complete 3 and let the rest of the athletes do “bonus” timed sprints. Remember, it’s not always what you do as a coach but the athlete’s interpretation of it. Specifically making an athlete do less is different than letting other athletes do more.

Will an extra sprint or two under 95% ruin an athlete? No. But will it put them into a slightly more decreased state of performance than they were before, detracting from the end goal? Yes. There is no right or wrong, but there are consequences of both.

However, I must say that within groups of 8-12 athletes, when I do have 1 or 2 that are under 95%, they are OK with not doing all the sprints because I have set the foundation of explaining the 95% concept over the prior training sessions and time together. This is effective because I give an explanation to the athletes and also give an alternative option. “You’re under 95% today, so I’m going to let the rest of the group do two more sprints, let’s go through our sled marching series/A-series/whatever it may be in the meantime, then we will all do our agility work together.”

Below 95% justifies and opens a check-in with athletes about how they are feeling that otherwise might not have happened.

Near 100%

On the flip side, if an athlete is very close to a PR, I will almost always give them “bonus” sprints. Knowing PR’s will not happen all the time, let’s take advantage of when they are close.

Just because my program says “4 timed sprints,” does not mean I have to stick to it. If the athlete’s body and mind are in a state to sprint fast and sprinting fast aligns with the training goal, squeeze everything out of that training session.

Knowing PR’s will not happen all the time, let’s take advantage of when they are close, says @CoachBigToe. Share on XConclusion

Here is a quick cheat sheet for combatting PR-itis with percentage thresholds:

Our athletes want to succeed more than anything. They will give their all every session, try their hardest on every rep, and consequently want to see improvements from their efforts. Likewise, as a coach, we want to see our athletes improve and achieve success.

Understanding PR-itis and the 95% threshold does not discredit the pursuit of becoming better, but do not let the stories your athletes are telling themselves and their misunderstanding of their own data discourage and derail them from their process of progress. Use 95% of your athlete’s PR to combat PR-itis, justify conversations about the process of progress, and help them rewrite the story of what their athletic development actually looks like.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF