There is no shortage of misconceptions surrounding the tactical population and approaches for strength and conditioning. For the better part of four years, I’ve been working predominantly with the Special Operations community and some Special Forces personnel. I work with both active duty and veteran populations, and it’s honestly difficult to describe some of the things I’ve heard about their training and the physical demands of their work—from the old adages like “resting is a sign of weakness” and “if it doesn’t hurt, it isn’t changing you” to more current and nuanced ideologies such as trend dieting, nonconventional health treatments, and extreme training endeavors.

The collective evolution of exercise and training across all military branches is actually quite fascinating, and it’s safe to say it has continued to improve and become more pragmatic for our service members.

Nevertheless, while there is almost always good intention, there is also a fair amount of misapplication, sometimes unbeknownst to the coach/instructor or the athlete. Through my work at Virginia High Performance (VHP), I’ve been afforded a tremendous opportunity to not only work with these individuals in a one-on-one manner but to do so with very little constraint or oversight. This opportunity has given me an enormous amount of time to try different methods and applications. Importantly, it has also given me the chance to make mistakes and see what definitely does not work.

With that in mind, in this article, I’d like to discuss what I feel are three of the most prominent misconception-based mistakes that occur when working with the tactical population.

Mistake #1. Attempting Movement Mimicry and Assimilation

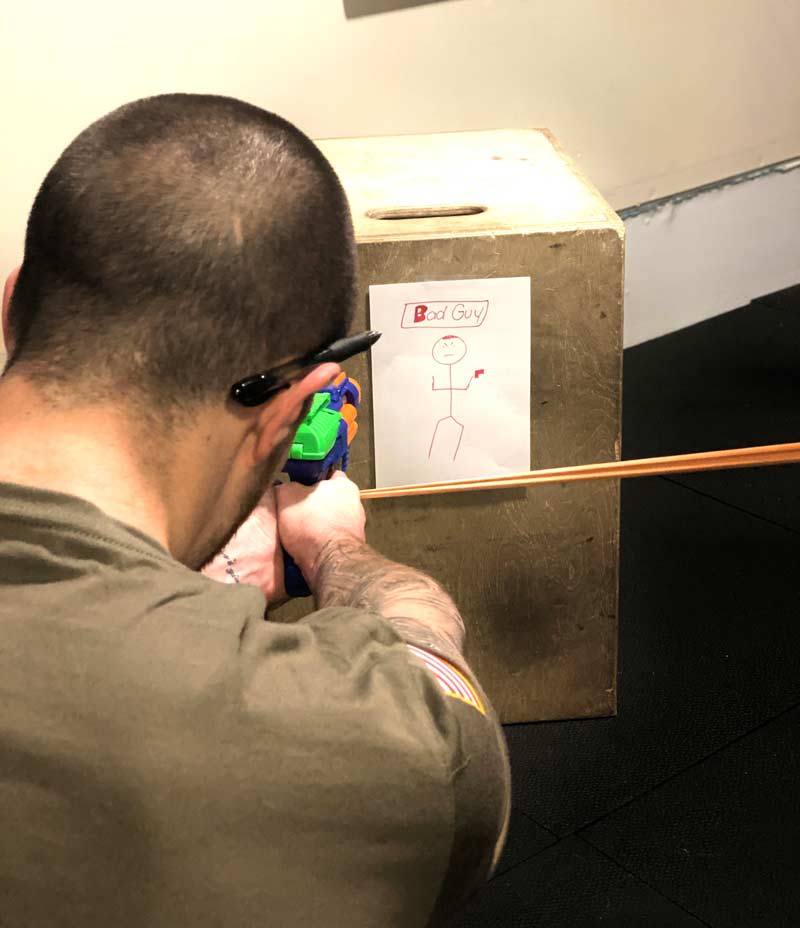

Without a doubt, the number one mistake I see made with tactical athletes is attempting to assimilate or replicate in the gym what they do professionally. There are many issues with this approach. Chief among them is that it gives the immediate impression that you really don’t understand the constructs of your role as a strength and conditioning coach—so, instead, you’re just going to play charades.

Without a doubt, the number one mistake I see made with tactical athletes is attempting to assimilate or replicate in the gym what they do professionally, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XIt’s important to recognize the substantial amount of time, intensity, effort, and resources put into our service members’ professional development. As such, they spend considerable time doing things like weaponry work, close-quarters combat (CQB), and marksmanship drills. Not to mention, they perform all these things under the direction of the most skilled instructors in the world. This makes it far from logical or practical to assume that the handful of hours we see someone in a gym will have any bearing on the thousands of hours of development they’ve had on base or command.

If you’re a strength and conditioning coach working with a basketball player, it wouldn’t make much sense to do things like a Pallof press while the athlete is dribbling a basketball. Why? Well, because the ball-handling aspect isn’t demanding enough for the athlete to promote any sort of adaptation, nor is the Pallof press promoting enough of a stimulus to drive a physical adaptation. Drills like this also lack the contextual demands for transfer (e.g., no defender or objective, making ball handling non-specific). Effectively, you’re just having them do two things worse at once and in a way that doesn’t provide any sort of meaningful outcome.

The exact same case applies to tactical athletes. So, rather than tying bands to guns for “resisted draw, aim, shoot,” simply assess them as athletes and do your job.

We are rooted in the foundations of anatomy, biomechanics, and physiology, and that is precisely how we can best influence our athletes—tactical or otherwise. My inherent goal is to simply be the best professional I can be and emphasize exactly what I know and can best provide for them. You’re not trying to make them better operators; you’re simply looking to influence or improve the physical qualities required of them to be more capable of performing their job.

This generally leads to basic things we would see in any other specific population:

- Injury management and restoration.

- Improving strength and speed.

- Improving conditioning.

- Restoring joint ROM/tissue quality as needed.

Leave the tactical skill development for the true experts, and you can focus on the components you’re able to influence and keep pushing.

Mistake #2. Finding Failure (Disproportionate Volume/Intensity)

Whereas the assimilation and movement mimicry tactics are poor training, overloading tactical athletes is nothing short of you becoming a liability to their career. Disproportionate volumes and intensities in training are clear injury risk amplifiers with this population—not just acutely or in the moment, but also setting them up for failure when they conduct their training at work. There is an inherent presence of high-volume, high-intensity demands for military operators, making them prime candidates for mechanical overload syndrome.

The best results I’ve had with tactical athletes in a four-week stretch have been the result of mostly unloading them and promoting more parasympathetic applications, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XAs performance coaches, when tactical athletes come to us, we must be measured with when and how we apply high force or high-volume loading. Beyond overstressing the athlete in a global sense through poor programming, we also need to be mindful of not overloading the athlete in a localized manner either. An easy example would be understanding the demands of kit, helmet, and night vision nods and that because of this demand, heavy back squatting is likely a poor option for most operators. Bad things happen when you place compression on top of compression (e.g., cervical discs, thoracocervical junction).

Additionally, assuming that they can endure it in the training setting just because they’re accustomed to high volume or extreme intensities is a critical disservice. In fact, I can say that the best results I’ve had with this tier of athletes in a four-week stretch have been the result of mostly unloading them and promoting more parasympathetic applications.

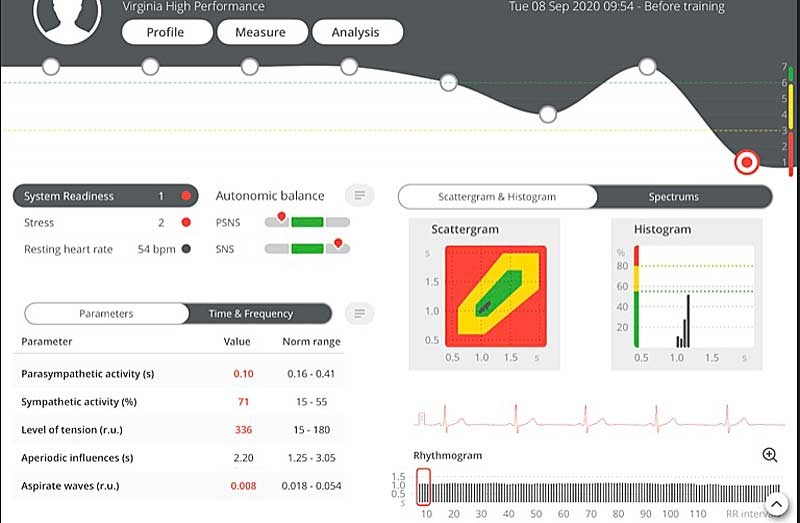

On average, roughly 70% of athletes we see are in an overly sympathetic state when they start with us. This means their body is in constant overdrive and has difficulty with sleep and/or relaxing, a compromised ability to recover, impaired metabolic function, and likely some level of endocrine strain. The crazy part is that without sophisticated tools like the Omegawave and Oura ring to measure this, you can rarely tell that they’re in a state of unrest or true exhaustion. Taking athletes with this kind of metabolic profile and throwing them into high-intensity or high-volume programming (e.g., heavy bench press, exhaustive “WODs” going for long-distance runs with a weight vest on) is unequivocally an imprudent approach.

Meet them where they are, and when working with active-duty populations, be sure you thoroughly understand the physical demands of their work environment. You’d be blown away by how much improvement someone can make when they just allow their body to downregulate for a few weeks and train with some level of intensity and consistency. It honestly doesn’t take much.

You’d be blown away by how much improvement someone can make when they just allow their body to downregulate for a few weeks and train with some level of intensity and consistency. Share on XBut no matter what style of training you believe in or utilize, just don’t simply crush them with overzealous intensities and volumes. I promise you don’t need to put on a show by demonstrating how “hard” you can push them. Just assess and apply what’s needed.

Mistake #3. Assuming Ability = Training

The last misconception I want to throw at you is to never assume that just because this population tends to be highly fit, they understand what they’re doing when it comes to training and nutrition. I have met some of the most wildly “in shape” and physically impressive individuals in the world through my work. I’ve worked with several individuals who’ve climbed Everest, Rainier, and other peaks and some who’ve completed Iron Mans, 100-mile runs, 24-hour marathons, and so forth.

I mention all that to say this: Do not confuse physical ability or genetics for knowing how to train optimally. I promise you, very few athletes actually do.

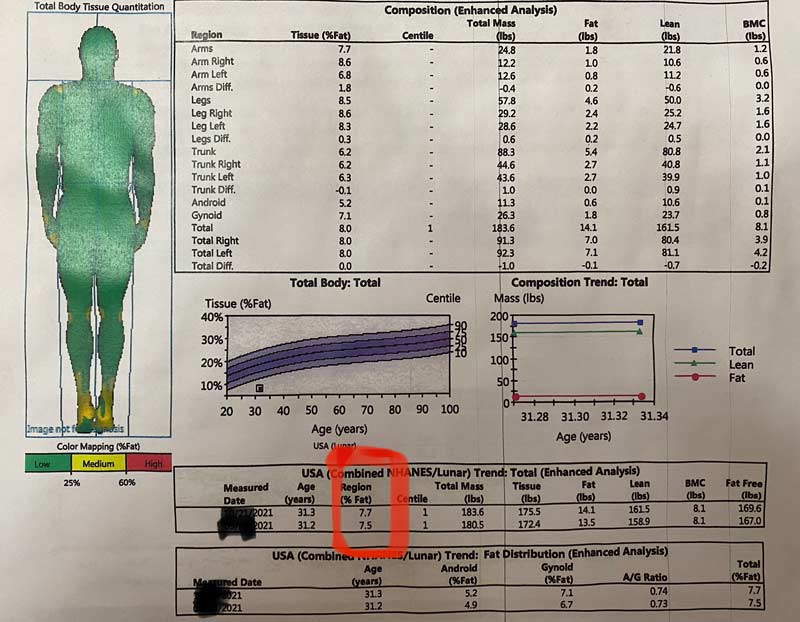

I’ll leave you with a quick story. I recently finished working with an athlete who checked IN at 7.5% body fat (only the second time I’ve seen someone under 10%). My initial thought was, well, what am I possibly going to be able to help this dude with? He had completed multiple marquee events and physical endeavors and was insanely committed to maintaining his training priorities and health-conscious lifestyle.

Never assume that just because this population tends to be highly fit, they understand what they’re doing when it comes to training and nutrition, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XAs it turned out, he was driving himself into a (somewhat severe) catabolic state. He was in a true overtraining state, resulting in metabolic/endocrine strain lethargy and hormonal decrements. Over the four weeks we worked together—and in conjunction with multiple modalities—we were able to, in a sense, reverse the effects of overtraining. This was achieved by improving his parasympathetic function and indirectly addressing his metabolic and endocrine impairments through strategic programming and nutritional planning.

The wild part is that we trained twice a day for four weeks, lifted heavy twice a week, and sprinted twice a week and still managed to improve PSNS/SNS balance and hormone profile. It was one of the wildest work situations I’ve had this year.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF